The Way Inn

‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Why collect something that’s made like that? What’s so interesting about them?’

‘Nothing, individually, nothing at all,’ she said. ‘You have to see the bigger picture.’

‘Late night?’

A second passed before I realised that I had been addressed, by Phil. His conversation with Rosa (or Rhoda) had lapsed. She prodded at her phone. Not really reading, not really listening, I had slipped into standby mode and was staring into space.

I made an effort to brighten. ‘Quite late,’ I said. ‘I got here at midnight.’ And then I had talked to the woman – for how long? – until Maurice detained me even later. Hotel bars, windowless and with only a short walk to your bed, made it easy to lose track of time.

‘I got here yesterday morning,’ Phil said. ‘We’re exhibiting, so there was the usual last-minute panic … got to bed late myself. Slept well, though. Did you get a good room?’

‘Yes,’ I said. In truth I was indifferent to it, precisely as the anonymous designers had intended. Indifferent was good. ‘It’s a new hotel.’ The same faces, the same conversations. People like Phil – inoffensive, with few distinguishing characteristics and a name resonant with normality. The perfect name, in fact. Phil in the blanks. Once I put it to a Phil – not this Phil – that he had a default name, the name a child is left with after all the other names have been given out. He didn’t take it well and retorted that the same could be said of my name, Neil. There was some truth to that.

Phil rolled his eyes. ‘Too new. Like one of those holiday-from-hell stories where the en suite is missing a wall and the fitness centre is full of cement mixers.’

The hotel looked fine to me – obviously new, but running smoothly, as if it had been open for months or years. ‘There’s a fitness centre?’

‘No, no,’ Phil said. He stabbed a snot-green cube of melon with his fork, then thought better of it and left it on his plate. ‘I don’t know. I’m talking about the Skywalk. The hotel is finished, the conference centre is finished, but the damn footbridge that’s meant to link them together isn’t done yet. So you have to take a bus to get to the fair.’ The melon was lofted once more, and this time completed its journey into Phil. He gave me a disappointed look as he chewed.

‘I don’t understand,’ I said, patting the information pack in front of me, a pack that contained a map of the conference facilities, lined up next to each other as neat as icons on a computer desktop. ‘The conference centre is two minutes away, but you have to take a bus?’

‘There’s a bloody great motorway in the way,’ Phil said. ‘No way around it but to drive. We spent half of yesterday in a bus or waiting for a bus.’

‘What a bore,’ I said. So it was; I was ready to bask in it. It’s part of the texture of an event, and if it gets too much there is always something to distract me. In this case it was Rhoda, Rosa, whatever her name was, still plucking and probing at her phone, although with visibly waning enthusiasm, like a bird of prey becoming disenchanted with a rodent’s corpse. Cropped hair, cute upturned nose – she was divertingly pretty and I remembered enjoying her company on previous occasions. If there was queuing and sitting in buses to be done, I would try to be near her while I was doing it. Sensing my attention, she looked up from her phone and smiled, a little warily.

Behind Rosa, a familiar figure was lurching towards the cereals. Maurice. It was a marvel he was up at all. The back of his beige jacket was a geological map of wrinkles from the hem to the armpits. Those were the same clothes he had been wearing last night, I realised in a moment of terror. I issued a silent prayer: please let him have showered. But maybe he wouldn’t come over, maybe he would adhere to someone else today. He picked up a pastry, sniffed it and returned it to the pile. A cup of coffee and a plate were clasped together in his left hand, both tilting horribly. My appalled gaze drew the attention of Rosa, who turned to see what I was looking at – and at that moment Maurice raised his eyes from the buffet and saw us. We must have appeared welcoming. He whirled in the direction of our table like a gyre of litter propelled by a breeze. Despite his – our – late night, he glistened with energy, bonhomie, and sweat.

It pains me to admit it, but Maurice and I are in the same field. What we do is not similar. We are not similar. We simply inhabit the same ecosystem, in the way that a submarine containing Jacques Cousteau inhabits the same ecosystem as a sea slug. Maurice was a reporter for a trade magazine covering the conference industry, so I was forever finding myself sharing exhibition halls, lecture theatres, hotels, bars, restaurants, buses, trains and airports with him. And across this varied terrain, he was a continual, certain shambles, getting drunk, losing bags, forgetting passports, snoring on trains. But because we so often found ourselves proximal, Maurice had developed the impression that he and I were friends. He was monstrously mistaken on this point.

‘Morning, morning all,’ he said to us, setting his coffee and Danish-heaped plate on the table and sitting down opposite me. I smiled at him; whatever my private feelings about Maurice, however devoutly I might wish that he leave me alone, I had no desire to be openly hostile to him. He was an irritant, for sure, but no threat.

‘Glad to see you down here, old man,’ Maurice said to me, not allowing the outward flow of words to impede the inward flow of coffee and pastry. Crumbs flew. ‘I was concerned about you when we parted. You disappeared to bed double quick. I thought you might pass in the night.’

‘I was very tired,’ I said, plainly.

‘Or,’ Maurice said, leaning deep into my precious bubble of personal space, ‘maybe you were in a hurry to find that girl’s room!’ He started to laugh at his own joke, a phlegmy smoker’s laugh.

‘No, no,’ I said. I am not good at banter. What is the origin of the ability to participate in and enjoy this essentially meaningless wrestle-talk? No doubt it was incubated by attentive fathering and close-knit workplaces, and I had little experience of either of those. At the conferences, I was forever seeing reunions of men – co-professionals, opposite numbers, former colleagues – who had not seen each other in months or years, and the small festivals of rib-prodding, back-slapping, insult and innuendo that ensued.

‘What’s this?’ Phil asked, clearly amused at my discomfort. Rosa/Rhoda’s expression was harder to read; mild offence? Social awkwardness? Disappointment, or even sexual jealousy? I hoped the latter, pleased by the possibility alone.

‘Neil made a friend last night,’ Maurice said. ‘I found him trying it on with this girl …’ he paused, eyes closed, hands raised, before turning to Rosa: ‘… excuse me, this woman … in the bar.’

‘Jesus, Maurice,’ I said, and then turning to Rosa and Phil: ‘I ran into someone I know last night and was chatting with her when Maurice showed up. Obviously, at the sight of him, she excused herself and went to bed.’

Maurice chuckled. ‘I don’t know. You looked pretty smitten. Didn’t mean to cock-block you.’

‘Jesus, Maurice.’

‘You’re a dark horse, Neil,’ Phil said.

‘Just a friend,’ I said, directing this remark mostly at Rosa/Rhoda.

‘Of course, of course,’ she said. Then she stood, holding up her phone like a get-out-of-conversation-free card. ‘Excuse me.’

‘So, what’s her name, then?’ Maurice asked. ‘Your friend.’

A sickening sense of disconnection rose in my throat. I didn’t know her name. Against astonishing odds I had re-encountered the one truly memorable stranger from the millions who pass through my sphere, and I had failed to ask her name or properly introduce myself. I had kept the contact temporary, disposable, when I could have done something to make it permanent. Maurice’s arrival in the bar had broken the spell between us, the momentary intimacy generated by the coincidence, before I had been able to capitalise on it. And now I was failing to answer Maurice’s question. He surely saw my hesitation and sense the blankness behind it.

‘Because you could ask the organisers, leave a message for her. They might be able to find her.’

‘She’s not here for the conference,’ I said, relieved that I could deviate from this line of questioning without lying.

‘Not here for the conference?’ Maurice said, now blinking exaggeratedly, pantomiming his surprise in case anyone missed it. All of Maurice’s expressions were exaggerated for dramatic effect. When not hamming it up, in moments he believed himself unobserved, his expression was one of innocent, neutral dimwittedness. ‘She must be the only person in this hotel who isn’t! Good God, what else is there to do out here?’

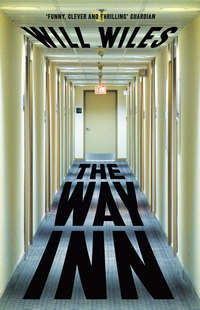

‘She works for Way Inn.’

‘Oh, right, chambermaid?’ Maurice said, and Phil barked a laugh.

I smiled tolerantly. ‘She finds sites for new hotels – so I suppose she’s checking out her handiwork.’

‘So she’s to blame,’ Phil said. ‘Does she always opt for the middle of nowhere?’

‘I think the conference centre and the airport had a lot to do with it.’

‘Aha, yes,’ Maurice said. Without warning, he lunged under the table and began to root about in his satchel. Then he re-emerged, holding a creased magazine folded open to a page marked with a sticky note. The magazine was Summit, Maurice’s employer, and the article was by him, about the MetaCentre. The headline was ANOTHER FINE MESSE.

‘I came here while they were building it,’ Maurice said. He prodded the picture, an aerial view of the centre, a white diamond surrounded by brown earth and the yellow lice of construction vehicles. ‘Hard-hat tour. It’s huge. Big on the outside, bigger on the inside: 115,000 square metres of enclosed space, 15,000 more than the ExCel Centre. Thousands of jobs, and a catalyst for thousands more. Regeneration, you know. Economic development.’

I heard her voice: enterprise zone, growth corridor, opportunity gateway. That lulling rhythm. I wanted to be back in my room.

‘Did you stay here?’ Phil asked.

‘Nah, flew in, flew out,’ Maurice said. ‘This place is brand new. Opened a week or two ago, for this conference I’m told.’

‘So they say,’ I said, just to make conversation, since there appeared to be no escaping it for the time being. To make conversation, to keep the bland social product rolling off the line, word shapes in place of meaning. While Phil again explained the unfinished state of the pedestrian bridge and our tragic reliance on buses, I focused on demolishing my breakfast. Maurice took the news about the buses quite well – an impressive performance of huffing and eye-rolling that did not appear to lead to any lasting grievance. ‘The thing is,’ he said, as if communicating some cosmic truth, ‘where there’s buses, there’s hanging around.’

There was no need for me to hang around. My coffee was finished, my debt to civility paid.

‘Excuse me,’ I said, and left the table.

Back in my room, housekeeping had not yet called, and the risen sun was doing little to cut through the atmospheric murk beyond the tinted windows. The unmade bed, the inert black slab of the television, the armchair with a shirt draped over it – these shapes seemed little more than sketched in the feeble light. Before dropping my keycard into the little wall-mounted slot, which would activate the lights and the rest of the room’s electronic comforts, I walked over to the window to look out. It wasn’t even possible to tell where the sun was. Shadowless damp sapped the colour from the near and obliterated the distant. The thick glass did nothing to help; instead it gave me a frisson of claustrophobia, of being sealed in. I looked at its frame, at all the complicated interlayers and the seals and spacers holding the thick panes in place: high-performance glass, insulating against sound and temperature, allowing the hotel to set its own perfect microclimate in each room.

A last look as I recrossed the small space – the brightest point in the room was the red digital display of the radio-alarm on the bedside table. I slid the card in the slot and the room came alive. Bulbs in clever recesses and behind earth-tone shades. Stock tickers streamed across the TV screen. In the bathroom, the ascending whirr of a fan. I brushed my teeth, stepping away from the sink to look at the painting over the desk, the only example of the hotel’s factory-made art in my room. The paintings in the bar had seemed so threatening last night – remembering the moment, the threat had come not from what lay within their frames but from the possibility of what lay outside them.

You have to look at the bigger picture, she said – and she meant it literally. If the paintings were simply scraps of a single giant canvas, they could be reassembled. And if they were reassembled, what picture formed? We were being fed, morsel by morsel, a grand design. ‘A representation of spatial relationships’ was how she described it. Her work, she said, involved sensing patterns in space – finding sites that were special confluences of abstract qualities, where the curving lines of a variety of economic, geographic and demographic variables converged. A kind of modern geomancy, a matter of instinct as much as calculation. She had a particular gift for seeing these patterns, any patterns. And the paintings formed a pattern. She was certain.

After midnight and after whisky, the idea found some traction with me. But in the morning, with the lights on, it sounded absurd. The artwork before me was simply banal, and I could not see that multiplying it would do anything but compound its banality. A chocolate-coloured mass filled the lower part of the frame, with an echoing, paler – let’s say latte – band around it or behind it, and a smaller, mocha arc to the upper left. Assigning astral significance to such a mundane composition was, frankly, more than simply eccentric, it was deranged. She had spent too long looking for auspicious sites and meaningful intersections for hotels, and was applying her divination to areas where it did not apply. I tried to trace the lines of the painting beyond the frame, to imagine where they might go next, extrapolating from what I could see. Spheres. Conjoined spheres. Nothing more. Spatial relationships – what did that even mean?

Spit, rinse. Bag, credentials, keycard. The shadows returned and I closed the door on them.

Music while waiting for the lift: easy-listening ‘Brown Sugar’. The lift doors were flanked by narrow full-length mirrors. Vanity mirrors, installed so people spend absent minutes checking their hair and don’t become impatient before the lift arrives. Mirrors designed to eat up time – there was some dark artistry, it’s true, but a decorators’ trick, not a cabalistic conspiracy. A small sofa sat in the corridor near the lift, one of those baffling gestures towards domesticity made by hotels. It was not there to be sat in – it was there to make the corridor appear furnished, an insurance policy against bleakness and emptiness.

In fact, given that this was a new hotel, it was possible, even likely, that no one had ever sat in it. An urge to be the first gripped me, but the lift arrived. Several people were already in it, blocking my view of infinity.

The first time I saw a hotel lobby, it was empty. Not completely empty, in retrospect: there were three or four other people there, a few suited gentlemen reading newspapers and an elderly couple drinking tea. And the hotel staff, and my father and mother. But my overriding impression was plush emptiness. Tall leather wing-back armchairs, deep leather sofas riveted with buttons that turned their surfaces into bulging grids. Lamps like golden columns, ashtrays like geologic formations, a carpet so thick that we moved silently, like ghosts.

Who was this fine place for? Surely not for me, a boy of six or seven – it had been built and furnished for more important and older beings. But where were they? When did they all appear?

‘Who stays in hotels?’ I asked my father.

‘Businessmen,’ my father said. ‘And travellers. Holidaymakers. People on honeymoon.’ He smiled at my mother, a complex smile broadcasting on grown-up frequencies I could detect but not yet decode. My mother did not smile back.

A waiter had appeared, without a sound. My father turned back to me, his smile once more plain and genial, eager to please his boy. ‘What would you like to drink?’

‘What is there?’

‘Anything you like.’

‘Coca Cola?’ I said, unable to fully believe that such a cornucopia could exist, that I could order any drink at all and it would be delivered to me.

Mother straightened like a gate clanging shut. ‘We mustn’t go off our heads with treats. How much will this cost?’ The question went to the waiter but her eyes were on me and my father, warning.

‘Darling, the company will pay.’

‘Will they? Do they know it’s for him? Is that allowed?’

‘They won’t know, and if they did, they wouldn’t mind. It’s just expenses.’

Expenses – another word freighted with adult mystery. Expenses, I knew, meant something for nothing, treats without consequences, the realm of my father; a sharp contrast to the world of home, which was all consequences. And expenses meant conflict, but not this time.

My father sold car parts, but he never called them car parts – they were always auto parts. Later, I learned specifics: he worked for a wholesaler and oversaw the supply of parts to distributors. This meant continual travel, touring retailers around the country. He was away from home three out of four nights, and at times for whole weeks. I yearned for the days he was home. We would go to the park, or go swimming – nothing I did not do with my mother, but the experience was transformed. He brought an anarchic air of possibility to the slightest excursion. A gleam in his eye was enough to fill me with mad joy. It was life as it could be lived, not as it was lived.

This was, in my father’s words, ‘a proper hotel’ – plush and slightly stuffy; English, not American; not part of a chain. It was in a seaside resort town, far enough from home for the company to pay for a room, but close enough for me and my mother to join him for a brief holiday, a desperate experiment in combining his peripatetic career with home and child-rearing. A fun and, much more important, normal time would be enjoyed by all – such was my mother’s anxiety on these points that she successfully robbed herself of any enjoyment. The hotel was quiet because it was off season. Winter coats were needed for walks along the grey beach; the paint was bright on the signs above the metal shutters, though the neon stayed unlit. The town was asleep, and we were intruders. In the hotel, we dined quietly among empty tables, an armoury of cutlery glinting unused, table linen like snow undisturbed by footsteps. I roamed the corridors. The ballroom was deserted and smelled of floor-polish. The banqueting hall was a forest of upturned chairs on tables. Everything was waiting for others to arrive, but who, and when? What happened here was of great importance and considerable splendour, but it happened at other times, and to unknown persons. Not to me.

Maybe my father moved in that world, where things were actually happening. There was a provisional air to him, as if he was conserving himself for other purposes. Even when he was physically present, he conducted himself in absences. He smoked in the garden and made and received telephone calls, speaking low. I would listen, taking care that he did not see me, trying to learn about the other world from what he said when he thought no one was listening. But he spoke in code: Magneto, camshaft, exhaust manifold, powertrain, clutch. And, rarer, another code: Yes, special, away, not until, weekend, she, her, she, she.

I was missing something.

The other lift passengers and I debarked into a lobby that had filled with people: sitting on the couches, standing in groups, talking on or poking at phones. Normally these communal places – the lobbies, the foyers, the atria – are barely used, inhabited only fleetingly by people on their way elsewhere, checking in or out, perhaps alone on a sofa waiting for someone or something. To see the space at capacity, teeming with people, was curiously thrilling, like observing by chance a great natural migration. This was it: I was present for the main event, when the hotels were at capacity and the business centres hosted back-to-back video conferences with head offices all over the planet. I could see it all for what it was and what it wasn’t. Because even when thronged with people, the lobby is still uninhabited – it cannot really be occupied, this space, or made home; it is a channel people sluice through. Those people sitting on the sofas don’t make the furniture any more authentic than the maybe-virgin seat I had seen by the lift. The space isn’t for anyone. My younger self might have been troubled by this thought, that even the main event could not give the space purpose – but now I had come to realise that the sensation was simple existential paranoia. I recognised the limits of authenticity.

Where there are buses, there is hanging around; Maurice’s dictum was quite correct. The driveway outside the hotel was protected by a porte-cochère. Under this showy glass and steel canopy, three coaches idled while conference staff in high-visibility tabards pointed and bickered, and desultory clusters of dark-suited guests smoked and hunched against blasts of cold, wet wind. The buses were huge and shiny, gaudy in banana-skin livery; their doors were closed. Evidently a disagreement or communications breakdown was under way – the attendants listened with fraught attention to burbling walkie-talkies, staring at nothing, or shouted at and directed each other, or jogged about, or consulted clipboards, but nothing happened as a result of this pseudo-activity.

I was about to retreat behind the glass doors, back to the warmth and comfort of the lobby, when I spotted Rosa (or Rhoda) standing alone among the huddle waiting for the buses, cigarette in one hand, phone apparently fused to the other. She had put on a brightly coloured quilted jacket and seemed unbothered by the cold and the icy raindrops that the wind pushed under the shelter.

‘Hey,’ I said.

Rosa looked at me without obvious emotion, although her neutrality could be read as wariness. ‘Hey.’

‘What’s going on?’ I said, nodding in the direction of the buses, where frenzied stasis continued. She looked momentarily dejected, and shrugged. We would never know, of course. The cause of this sort of hold-up was rarely made clear, it was just more non-time, non-life, the texture of business travel. Hotel lobbies and airport lounges are built to contain these useless minutes and soothe them away with comfortable seats, agreeable lighting, soft music, mirrors and pot plants.

‘I’m sorry we didn’t get much of an opportunity to talk back there,’ I said. Rosa’s edge of frostiness towards me, her shrugs and monosyllables, bothered me. I was certain we had got on well in the past, and she seemed an excellent candidate for some conference sex, if we could get past this froideur. My failure to capitalise on the coincidence in the bar last night had left a sour aftertaste. Some sex would dispel that; it would divert me, at least. If Rosa reciprocated.

‘You seemed busy,’ she said.

‘Nothing important.’

‘Who was that man who joined us?’

‘Maurice? I thought you knew him. A reporter, for a trade magazine.’

‘I’ve seen him around.’

‘He’s hard to miss.’

‘A friend of yours?’

‘Not really.’

‘So this girl he mentioned …’

Sexual jealousy, was it? That was a promising sign.

‘You shouldn’t believe a word Maurice says,’ I said. ‘He was only trying to stir up trouble. I was having a drink with an acquaintance. You know how you keep running into the same people at these things. Which can be a very good thing.’

‘Yeah.’ I was rewarded with a shy smile. Pneumatics hissed – one of the buses was opening its doors at last.

I decided not to overplay my hand – there would be other opportunities. ‘Really good to see you again,’ I said. ‘Let’s talk later.’