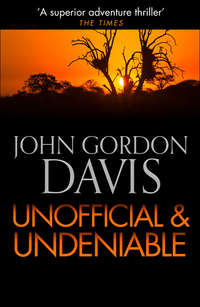

Unofficial and Deniable

‘Is that Buttons and Bows Night Club?’ Dupont said.

Harker closed his eyes, his heart knocking. ‘Sorry, wrong number.’ He hung up.

Harker slumped, then picked up his cellphone, his hand shaking. He dialled.

‘Buttons and Bows,’ Clements said.

‘I want to speak to Mr Buttons, please.’

‘He’ll call you back in about twenty minutes, sir.’

It was a long twenty minutes waiting for Clements’ next call. ‘Awaiting your pleasure, sir,’ he said.

Harker picked up his holdall and clambered up the narrow staircase into his upper office. He opened the big front door of Harvest House and stepped out into the spring night. The car was parked fifty yards down the road: the driver flashed his headlights once. Harker climbed into the front passenger seat. A man called Parker, one of Clements’ salesmen, was at the wheel. ‘Good evening, sir,’ they all said.

‘Good evening,’ Harker said tensely. ‘Let’s go.’

At nine o’clock that Saturday night they were creeping through the forest, approaching the farmhouse. Now they were all in black tracksuits, wearing balaclavas, carrying the machine-pistols Harker had distributed.

The clapboard house was about fifty years old, the paint peeling off the wood, the yard around it sprinkled with weeds and shrubs. The house was in darkness. The listening gear was in position. Harker gave his instructions and Clements moved to take cover facing the front door, Spicer went off to cover the kitchen door, Trengrove disappeared around the other side of the house to the living room window. Harker remained with the listening device, covering the dining-room French window. They settled down to wait.

It was a very long hour before the headlights came flicking through the forest. The car came up the winding track into the yard, its headlights now blinding. Harker lay beside the listening gear, his heart pounding; the vehicle’s doors opened and one by one five dark figures clambered out. They were hardly talking, only a mutter here and there as they stretched and reached for luggage. Then, while the headlights illuminated the kitchen door, they trooped towards it, carrying their briefcases and baggage. For the first time Harker could distinguish the blacks from the Cubans, but he could not identify anybody. They clustered around while one of the Cubans selected and inserted a key.

Harker snorted to himself. It would have been an ideal moment to hit the whole damn lot of them: no fuss, no risk. But no – goddam Dupont wanted to record what they talked about first. The Cuban unlocked the door and they filed inside. Lights went on. Harker glimpsed them filing through the kitchen into the dining room. They clustered around the table, and one of the Cubans produced a bottle from his briefcase.

Harker put on the headphones of the listening device. He could hear mumbled speech. He turned the tuning knob and the volume. Suddenly he heard a Cuban say, ‘Close the curtains. Sit down, please …’ He heard the scraping of chair legs on the floor. More mumbles. The tinkle of liquor being poured. Then the meeting began.

Harker listened intently, his tape-recorder turning; then he closed his eyes in relief. Thank God … Thank God this murder was not unjust. The bastards were certainly plotting murder. Mass murder. Planning to detonate three car-bombs at twenty-four-hour intervals: the first at the Voortrekker Monument on a Sunday, the second at the Houses of Parliament on Monday, Johannesburg’s international airport on Tuesday. Harker smiled despite himself – the chain of events would be effective: the Voortrekker Monument job would infuriate, the Houses of Parliament job would vastly impress, the Johannesburg airport job would downright terrify. The psychological impact upon the South African public, coming one after the other, boom boom boom, would be enormous. In fact, listening to the muffled indistinct speech, Harker was surprised they settled for only three bombs – why not half a dozen, throw in the Union Buildings in Pretoria where all the top government departments hang out, the Reserve Bank down the road and, say, the City Hall. Harker had always wondered why the ANC hadn’t done all that years ago – they really were, militarily speaking, a milk-and-water bunch. MK, the Spear of the Nation, the ANC’s army, had never waged a battle. The only thing that gave them clout was the moral turpitude of apartheid.

For an hour Harker tried to listen to the plotting going on in the house, over the coughs and mumbles and mutters and occasional laughter, the glug of liquor and the click of cigarette lighters; he could only make out snatches of detail and he hoped the tape-recorder was picking up more. Then suddenly the meeting sounded as if it was over: he heard a burst of song in Spanish, followed by guffaws.

Harker took a deep breath – it was time to hit. He took off his headphones and whispered into his radio transmitter.

‘H-hour coming up. Do you read me? Come in one at a time.’

‘One, copy,’ Clements said.

‘Two, copy,’ Ferdi Spicer said.

‘Three, copy,’ Trengrove said.

‘Okay,’ Harker said, ‘we hit on zero … Five … Four … Three … Two … One … Zero!’

Out of the forest sprang the four dark forms. They ran through the darkness at the house. Harker raced up to the curtained dining-room French window, a stun grenade in his hand: he yanked out the pin with his teeth and hurled it through the window. There was a shattering of glass, then a detonation that seemed to shake the earth. Then there was a crack as Spicer kicked the kitchen door in, another as Clements did the same to the front door. Harker burst through the window and opened fire. And there was nothing in the world but the popping of his machine pistol, then the noise of Spicer’s and Clements’ as they covered the two principal escape routes.

In the cacophony Harker did not hear the shattering of the living room window as a black South African called Looksmart Kumalo dived through it, through Trengrove’s hail of bullets, scrambled up and fled off into the black forest. Trengrove went bounding frantically after him, gun blazing, but in an instant the darkness had swallowed him up. Trengrove went crashing through the black undergrowth, wildly looking for the runaway man, but Looksmart Kumalo, badly wounded, was hiding under some bushes. Trengrove crashed about for several hundred yards, then he turned and went racing back to the farmhouse.

Harker was frantically collecting up all the documents, baggage and briefcases while Clements and Spicer were fixing explosives to the dead bodies. ‘Where’s the other body?’ Clements demanded.

‘Sir!’ Trengrove shouted. ‘He escaped into the forest!’

‘Christ!’ Harker stared. ‘Christ, Christ, Christ!’

‘Go after him, sir?’ Clements rasped.

‘Yes!’ Harker shouted. ‘Spicer stays and finishes the explosives! Rest of you go. Go!’

For twenty minutes Harker, Clements and Trengrove thrashed through the black undergrowth of the forest, trying to flush out the runaway, hoping to stumble across the dead body. It was hopeless – nobody can track in the dark. After twenty minutes Harker barked a halt. If the bastard survived he was unlikely to tell the American police that he was attacked during a murderous conspiracy meeting in an illegal Cuban safe-house.

‘Back!’ Harker rasped. ‘Get the hell out of here!’

Spicer was desperately waiting for them, the explosives emplaced, the listening gear and the seized documents ready to go. Harker spoke into his radio to the getaway car: ‘Venus is rising!’

The men went racing up the dark track towards the tarred road. They were several miles away, speeding towards Manhattan, when the house disintegrated in a massive explosion, the bodies blown to tiny pieces.

9

It was always the same after an action. Before going into battle he was very tense but afterwards, when the dust had settled and the bodies had been counted, he slept as if he had been pole-axed even if he knew the action was to resume at dawn – he felt no remorse about the enemy, only grim satisfaction and relief to have survived. It was only the conscripts, the civilians in uniform, who sometimes felt remorse, but usually that didn’t last long either because few experiences are more antagonizing than having, some bastard trying to shoot the living shit out of you.

Harker woke up that Sunday afternoon rested for the first time in a week, permitting himself no feeling of guilt. The die was cast, nothing could change it. It had been a legitimate military operation and had saved civilian lives. It was front-page news in most of the papers: there were photographs of the area where the safe-house had stood, the earth and shrubbery blackened and blasted. There was one survivor in critical condition: an ‘adult male of African origin now in hospital, with multiple injuries, including loss of one eye and an arm so badly mutilated by gunfire that it had to be amputated below the elbow’. The FBI were investigating: they had no comment yet but the local sheriff, who was first on the scene, was moved to hint that this was ‘probably a gangland slaying, probably to do with drugs’. Investigations were continuing.

Harker felt a stab of guilt through a chink in his armour when he read about the mutilated survivor, as yet unidentified, but he thrust it aside – he had seen plenty of his soldiers mutilated over the years: if you play with fire you must expect to get your fingers burnt – the bastard had been plotting far worse, he was lucky to be alive and if he’d been caught in South Africa he would have been hanged after the police had wrung the truth out of him. Harker had no fear that the man could be dangerous: no ANC official would be so dumb as to tell the FBI he was meeting with Fidel Castro’s henchmen on holy American soil. Without much difficulty Harker parried the thrust of guilt as he encoded his report to Dupont that Sunday afternoon, and when his computer began to print out the information from Washington that the survivor was now positively identified by the CIA as Alexander Looksmart Kumalo, his remorse evaporated further. Looksmart Kumalo was well known to Military Intelligence as one of the ANC’s sabotage strategists.

That afternoon Harker took the shuttle flight to Washington to deliver to Dupont all the documents seized at the farmhouse. He had not read them; he had tried, he could read Spanish with difficulty but he could not concentrate; indeed he did not want to know any more than he had to about the misery of war and murderous skulduggeries in its name, and he wanted to forget his work of last night. But when he walked into the soundproof office behind the reception desk of the Royalton Hotel a happily drunk Dupont not only thrust a large whisky at him after pumping his hand in congratulation – ‘Jolly good show, fucking good show! Sanchez and Moreno!’ – but also insisted Harker give him a blow by blow account. And sitting in the corner was the CIA man whom Harker knew only by the codename ‘Fred’, the guy who was Dupont’s handler or contact with the United States’ ‘Dirty Tricks Bureau’ as he called it, and Fred wanted every detail on tape.

‘Fucking good show …’ Dupont interjected frequently.

Neither Dupont nor Fred was unduly concerned about the survivor, Looksmart Kumalo. It was a pity, of course, that he had not perished with the rest of the blackguards but there was no danger of the bastard spilling the beans: he would be debriefed by the CIA and advised, ‘in the nicest possible way’, that not only was his liberty at stake because of the cocaine the FBI had planted on him, but his health was also because – if he didn’t have a mysterious fatal heart attack in hospital – he would be deported to South Africa where he belonged and where he would receive a warm welcome from the authorities if he opened his big mouth. And if he broke the bargain he was being so generously offered, the British MI5, France’s Sûreté and most of the civilized world’s secret services would have him prominently on their shit-list.

‘He won’t talk publicly,’ Froggy Fred croaked, ‘and if he does they’ll be the last words he utters.’

‘You planted cocaine on him?’ Harker frowned. ‘I thought the FBI were going to blame the whole thing on the Cuban exile community in Miami. Now you’re going to claim it was a drug-war assassination?’

‘Both,’ Fred rumbled. ‘We blame it on both, as alternative possibilities, to raise confusion.’

Dupont leered happily, stroking the pile of documents. ‘He’ll keep his mouth shut, don’t worry …’

It was after midnight when the debriefing was declared over and a taxi was summoned to take Harker back to the airport. Dupont offered him a room in the hotel –‘The presidential suite indeed’ – and Fred volunteered to throw in a good hooker ‘on Uncle Sam’ – ‘Or two!’ Dupont cried – but Harker just wanted to get the hell, away from yesterday, from these awful guys, from this hotel where they festered.

As he climbed into the taxi, Dupont breathed alcoholically through the window. ‘Fucking good show! Now you relax, disappear to the beach for a few days, then get on to the Bigmouth case …’

He did disappear to the coast, but not to enjoy himself – it was to brood. Ah yes, his soldier’s conscience was clear, more or less, but even soldiers sometimes want to be alone after they have done battle, spilt voluminous blood, mourn not for the enemy but the whole dreadful business of taking so much life. And he did not want to ‘get on to the Bigmouth case’ – he felt a fraud. He was a fraud. Jack Harker dearly wished he was not bound to take the beautiful Josephine Valentine to lunch next Saturday, he wanted to be alone, he dearly wished he did not have to pose fraudulently as her potential publisher in order to further the ends of apartheid. Josephine Valentine’s book was hardly a legitimate military target.

And he would not do so.

No, he would not do so. Jack Harker refused to defraud Josephine Valentine any further by pretending that he was interested in publishing her book. He would have to pay her the courtesy of reading her ten chapters, and he would give her his honest opinion, but he would tell her immediately thereafter that Harvest would not publish it. He was not going to give her false hope, and he certainly was not going to obey orders and bury her book, kill it by publishing it badly. Fuck you, Felix Dupont.

Having made that decision he felt better. On Saturday, when he drove back to Manhattan, he was again looking forward to having lunch with one of the best-looking women in New York.

When Josephine Valentine came sweeping into the yacht club dining room, clutching her file, beaming, hand extended, she was even lovelier than he remembered.

‘Hi!’ She pumped his hand energetically: hers was warm and both soft and strong. She was a little breathless, as if she had been hurrying. ‘Am I late?’

‘Indeed you’re two minutes early,’ Harker smiled. ‘You look beautiful.’

‘Thank you. Well …’ She plonked the file down on the table. ‘Here it is.’ But she put her hand on it. ‘Please, don’t look at it now. I want you to give it your undivided attention at home. And,’ she grinned, ‘I’m nervous as hell.’ She sat.

Oh dear. ‘Don’t be, I know you write well.’ Harker sat down. And he decided that right now was the moment to start extricating himself. ‘And I’m not the only publisher in town. Indeed you’ll probably do better with a bigger house.’

Consternation crossed her lovely face. ‘But you will consider it? Are you saying you’re not interested any more?’

Oh Christ. ‘I’m just being realistic, for your sake.’ He smiled. ‘On the contrary, I’m the one who should be nervous that you’ll take it to somebody else.’

Josephine sat back and blew out her cheeks. ‘For a moment I thought you were trying to tell me something.’ Then she said anxiously, ‘You will be brutally honest with me, won’t you?’

‘Of course.’

‘Okay.’ She sat back, with a brilliant smile. ‘And now let’s stop talking about it – I’ve been burning the midnight oil all week.’

‘So what’ll you have to drink?’

‘A double martini for starters. Followed by a bucket of wine. And remember I’m paying.’

‘You are not.’ The fucking CCB was paying.

They had a good time again that day. They laughed a great deal, drank a lot, became very witty and wise. Harker got into a mood to celebrate too, but he was not sure what: he still felt a fraud. And, God, he just wanted to get this masquerade of being her potential publisher over so he could do what publishers should not do – make a pass at an author. Oh, to take her hand across the table, look into her blue eyes, tell her how beautiful she was, to feel her body against his, to go through the delightful process of courtship: but as long as he was defrauding her his conscience would not permit it, his head had to rule his loins. So the sooner he went through the motions of reading her typescript, grasped the nettle and told her that Harvest could not publish it, the better.

‘So tell me, Major Jack Harker,’ she said over the rim of her first glass of Irish coffee, ‘whatever happened to Mrs Harker?’

‘There hasn’t been one. There very nearly was, but she changed her mind. One of the casualties of war. She’s now Mrs Somebody Else.’

‘Oh. Well, all I can say is that she was either very, very stupid or Mr Somebody Else must be very, very nice. So tell me …’ she raised her glass to her wide full lips and looked at him, ‘is some lucky American gal filling her stilettos?’

‘Nobody special.’ He felt himself blushing. ‘And how about you?’

She grinned. ‘Nobody special. I’ve only just hit town after a long time away.’

Oh, Harker badly wanted to know about her past, how many of the legends about her were true. In particular he wanted to know about that dead Cuban lying on the floor of the building at Bassinga when she had tried to kill herself – but the time was not right for a confession that he had killed her lover, and doubtless never would be.

‘I’m sure you’ve been close to marrying?’ he said.

‘Several times. But, at the last minute, there was always something amiss.’ She flashed him a smile from underneath her dark eyebrows. ‘Like, not enough soulmateship.’ She added: ‘I’ve got the feeling you know what I’m talking about.’

‘Soulmates? Sure. Lovers who think and feel alike. Share the same interests.’

‘And passions. Interests and passions. Like…Justice. And Democracy. Freedom. A fair wage for a fair day’s labour. And poetry, and music. And … God.’ She looked at him seriously, then flashed him a smile. ‘All that good stuff.’

‘And have you ever found it?’

Josephine nodded sagely at her glass. ‘I thought so, several times. But each time it turned out to be a false alarm. Or something like that. Until the last time, I think. Maybe. But he was killed.’

Oh Christ. Harker waited, then said, ‘How?’

She said to her glass, ‘He was a soldier, like you.’ She smirked. ‘And he lost his life fighting you guys.’ She looked up. ‘The Battle of Bassinga? Mean anything to you?’

Harker feigned a sigh. What do you say? ‘It was a big do, I believe. I was in hospital at the time, wounded in an earlier action, the one that pensioned me out.’ He glanced at her. ‘So, what happened exactly?’

Josephine took a sip of Irish coffee. ‘I’d been living with him in his base camp for about a month. First met him up north in Luanda, then flew down with him to cover the southern front. We were asleep in his quarters when your guys struck, just before dawn. Helluva mess. Anyway, Paulo got shot at the beginning. So did I, but that was later on.’

So she wasn’t admitting attempted suicide. ‘You were shot in the cross-fire?’

‘When Paulo was shot I went berserk, I grabbed his AK47 and started firing out the window. There was a box of loaded magazines and I just kept firing, slapping in one magazine after another. Stupid, because journos aren’t supposed to become combatants if they don’t want to be treated as an enemy, but I was frantic about Paulo. Anyway, finally a bullet got me. Here.’ She tapped her left breast. ‘Missed my heart, fortunately. Next thing I knew I was being loaded into one of your helicopters and flown off to one of your bases, where they patched me up – which was nice of them, seeing as I’d been trying to shoot the hell out of them an hour earlier. Then they deported me.’

‘Oh, yes, I heard about this. So you’re the blonde bombshell who threatened to sue us. Wasn’t there a row about your photographs?’

She smiled. ‘Your guys developed my film to see what they could find out about the enemy’s hardware. I kicked up a fuss and they gave me my negatives back.’

‘Did they interrogate you?’

‘Sure, but I told them to go to hell.’ She added, ‘I must admit, grudgingly, that they were perfectly gentlemanly about it.’

Harker wondered what she would feel and say if he told her he knew the truth. ‘And this man Paulo – you were in love with him?’

She nodded. ‘Wildly. Or I thought so. I’d only known him for a little more than a month. Now with the wisdom of hindsight I realize that I was only infatuated, and confused by my admiration for him. He was a very admirable man. And swashbuckling.’ She smiled.

‘And handsome, no doubt.’

‘But that doesn’t cut much ice with me. It is what’s in here that counts.’ She tapped her heart. ‘And here.’ She tapped her head. ‘He was an entirely honest, dedicated social scientist, if that’s the word, dedicated to the well-being and betterment of his people – a true Christian, but for the fact that he was an atheist, of course, being a communist. Dedicated. His men loved him. Several medals for bravery. And ‘a great sense of humour. And a great reader, a very good conversationalist in both Spanish and English.’

Harker couldn’t stand the man. No doubt a fantastic Latin lover too. ‘Sounds good. But?’

‘But,’ Josie smiled, ‘I now realize it wouldn’t have worked. For one thing I’m not a communist. For another I espouse God. English is my mother tongue, and freedom of speech and of the press is my credo. And I’m a fully liberated Americano who regards herself as every inch her man’s equal, not as a Latino wife. Oh, he was macho, Paulo. Machissimo.’ She smiled wanly. ‘And there was something else wrong. I knew it at the time but wouldn’t admit it to myself – there was lots of lust, and lots of fun, but I knew deep down that it was just a rip-roaring affair, not love with a capital L.’

Harker was pleased to hear that: Señor Paulo sounded quite a tough act to follow. Before he could muster something appropriate Josephine asked with a smile, ‘And what about that extremely silly lady who nearly became Mrs Harker, then lost her marbles?’

Harker smiled. ‘Well …’ He was tempted to exaggerate, to match her description of Paulo, then he decided to do it straight. ‘Well, rather like your Paulo, who had something missing, my Pauline – and that was truly her name, would you believe the coincidence? Pauline was also dedicated to liberal politics, uplifting the Africans. Trade unionism, defeating apartheid, et cetera. She was a teacher, and she was going to set the world on fire. Anyway, I was off in the bush most of the time, dealing with her pals the enemy, and she met this crash-hot stockbroker who took her away from it all.’

‘And the first you knew about it was when you came back from the bush?’ She shook her head. ‘Well, he must have been one hell of a sexy stockbroker.’ She smiled at him.

The compliment made Harker’s heart turn over. And he longed to reach out across the table for her hand.

Then she confused him by changing the subject abruptly. ‘And tell me, do you believe in God?’

For the next half hour, through another round of Irish coffees, religion was the animated if solemn topic. Yes, Harker did believe in a Creator but he had arrived at this conclusion by logic rather than by what had been instilled into him at Sunday School: the upshot was an inability, on the evidence, to conclude whether He was the Christian, Islamic, Buddhist, African or some other kind of god. Josephine on the other hand described herself as ‘eighteen-carat Catholic’: ‘Alas, I believe in Heaven and Hell, the whole nine yards.’