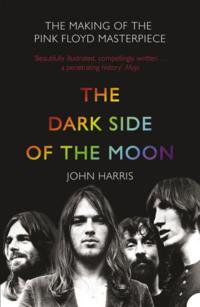

The Dark Side of the Moon: The Making of the Pink Floyd Masterpiece

Piper’s other most notable aspect was Barrett’s lyrics. Whereas the music betrayed both power and sophistication, his words were recurrently grounded in the fragile simplicity of childhood, often so innocently expressed that one cannot help but arrive at a crude explanation for Barrett’s breakdown. How, it might be asked, could the kind of mind that came up with ‘The Gnome’ (‘Look at the sky, look at the river – isn’t it good?’), or the rose-tinted memoir ‘Matilda Mother’ – a loving remembrance of Winifred Barrett reading her son fairy-tales – adapt to the hard demands of adulthood, let alone the pressures that arrive in the wake of commercial success? Rock music, even then, was only partly founded on talent and creativity; if a musician was to survive, he or she also needed wiliness, resilience, and determination: in short, a keen sense of ambition.

‘Syd was a real hippie in a lot of respects,’ says Aubrey Powell. ‘If he had a guitar, and he could play some tunes, and sing some of his wonderful bits of poetry, and somebody could supply him with a nice space where he could play his Bo Diddley albums, that was enough. Even when he was earning money, Syd wasn’t living extravagantly. He was quite happy to live in a flat with no furniture in it. He was a real bohemian in that sense. I never felt he was pop star material; he wasn’t made for it.’

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn was preceded by ‘See Emily Play’, which thrust Pink Floyd into dizzying territory, climbing to number six on the British singles charts, and confirming the necessity of endlessly touring the country so as to prolong their success. By the time of its release, however, Syd Barrett was beginning to fall apart. ‘He became steadily more remote,’ says Peter Jenner. ‘He was hard to talk to. From being occasionally withdrawn, he got very strange. And his life became more and more his own life until we hardly saw him. That was when I really began to worry that there was something going seriously awry.’

Most of the songs on Piper had been written during a concerted burst of creativity in late 1966 and early 1967, when Barrett was living in an apartment on Earlham Street in central London. In the recollection of his flatmate, the group’s lighting technician Peter Wynne-Wilson, ‘Those were halcyon days. He’d sit around with copious amounts of hash and grass and write these incredible songs. There’s no doubt they were crafted very carefully and deliberately.’

By April 1967, Barrett had shifted his base of operations to 101 Cromwell Road, an address in Earls Court. Among the residents was one Brian ‘Scotty’ Scott, remembered by one Pink Floyd associate as ‘one of the original acid-in-the-reservoir, change-the-face-of-the-world missionaries’. For Barrett, the upshot of such company was clear enough. ‘He seemed to be on acid every day,’ says Peter Jenner. ‘We heard he was getting it in his tea every morning.’ This, it was safe to say, was hardly the ideal lifestyle for someone whose sensibilities were proving ever more fragile, but for the moment, neither the band nor their associates saw fit to intervene.

‘Everything was coming at us from all directions,’ says Jenner. ‘In the early days, when Syd was at Earlham Street, I’d just pop round there quite often and see him. As they became bigger, he moved into his own social scene. We saw less of him; he became more distant. We realized there was something strange going on in Cromwell Road, but I didn’t know the people who were there. And I never really felt it was my job to find out. It was only when it became clear that there was a problem with gigging – with work … In those days, it was really uncool – man – to pry into someone’s life.’

When the group and their associates attempted to deal with Barrett’s predicament, they initially did so in the context of a quintessentially 1960s invention known as anti-psychiatry, one of the many strands of thought beloved of the upper echelons of the Underground. Relative to the other credos of the period, it was a neat fit: just as underground insiders like Richard Neville believed that the key to social change lay with the moral and emotional liberation of the individual, so anti-psychiatry held that the shortcomings of twentieth-century civilization were reflected in isolated cases of supposed mental breakdown. The key pioneer of all this was a Scottish doctor named R. D. Laing, born in 1927, but sufficiently radical in his outlook to be co-opted into the Underground by his younger admirers.

Laing was fleetingly involved in the Notting Hill Free School, became a regular presence at Underground events, and was decisively tied into the mood of 1967 by that year’s publication of a polemic, drawn from his lectures, entitled The Politics of Experience. Schizophrenia, the book claimed, arose from a rational desire to opt out of impossible circumstances: ‘The experience and behaviour that gets labelled schizophrenic is a special strategy that a person invents in order to live in an unlivable situation.’ Moreover, the supposed schizophrenic might actually be capable of greater insights and achievements than the allegedly sane: in Laing’s view, asking whether the condition was wholly due to a deficiency on the part of the sufferer was ‘rather like supposing that a man doing a handstand on a bicycle on a tightrope 100 feet up with no safety net is suffering from an inability to stand on his own two feet. We may well ask why these people have to be, often brilliantly, so devious, so elusive, so adept at making themselves so unremittingly incomprehensible.’ Underlying all this was the belief that society so squashed individual potential that mental dislocation was inevitable. ‘The ordinary person,’ Laing wrote, ‘is a shrivelled, desiccated fragment of what a person can be.’

‘There were a whole team of them who all believed it was rather good to be mad, and it was the rest of us who were making less sense,’ remembers Roger Waters. ‘And it may be that there is something to be said for the idea that people who we claim to be mad might see things that the rest of us don’t, and their experience can illuminate life for us. He seemed to be thinking that insanity might be a very subjective idea; that perhaps madness might give people some kind of greater insight. In Syd’s case, you could say that it was his potential for decline into schizophrenia that gave him the talent to express mildly untouchable things. But I confess that I feel that a lot less now than I may have done then.’

‘With Syd’s very clear mental problems,’ says Peter Jenner, ‘there was a sense of, “Well, is it our fault or his? Who’s actually mad: him or the rest of us? Is the madman speaking truth?” For someone like me, who was quite young and pretentious and intellectual and read too many books, it was very hard to cope with. We knew something was a bit weird, but on the other hand, the Floyd’s whole experience had been a bit weird. We were out there on the edge, so what was wrong with Syd being a bit out there on the edge? At what point does being original and new and different become loony? It seemed impossible to say. It’s a continuum.’

On one occasion, Barrett’s colleagues arranged for him to meet Laing, only for Syd to decide at the last moment that he was unwilling to go through with it. ‘He wouldn’t get out of the car,’ says Roger Waters, who accompanied Barrett to Laing’s house. ‘And I’m not sure that was necessarily a bad thing. Laing was a mad old cunt by then. [Pause] Actually, “cunt” is a bit strong. But he was drinking a lot.’

Contrary to the fashionable thinking of the time – and in keeping with his distanced relationship with the Underground – Waters claims to have held fast to a conventional diagnosis of Barrett’s problems. ‘Syd was a schizophrenic,’ he says. ‘It was pretty clear to me that that was what was the matter with him. But not everybody would accept that. I had ties with Syd’s family going back a fair way, and I can remember telephoning one of Syd’s brothers and telling him he had to come and get Syd, because he was in a terrible mess, and he needed help. And the three of us sat there, and in effect, Syd did a fairly convincing impression of sanity. And his brother said, “Well, Roger says Syd’s ill, but that’s not the way it seems to me.”

‘There was eventually a lot of argy-bargy with his family, and a lot of stuff about whose fault it was,’ says Waters. ‘His mother blamed me entirely for Syd’s illness. I was supposed, I think, to have taken him off to the fleshpots of London and destroyed his brain with drugs. And the fact is, I never had anything to do with drug-taking. Certainly not with Syd, although he did indulge in lots of acid, which given the fact that he was an incipient schizophrenic was obviously the worst possible thing in the world for him. But mothers have favourite sons – and if something goes wrong, they have to find someone to blame.’

Barrett’s decline took place against the backdrop of frantic activity: the aforementioned US tour, a run of British shows with The Jimi Hendrix Experience and The Nice, and attempts to record a new single, so as to capitalize on the success of both ‘See Emily Play’ and The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. The fact that Barrett was able to honour the vast majority of his commitments seems faintly miraculous, although his behaviour was leading to snowballing tension within the group. While Waters, Mason and Wright would attempt to found the band’s shows on at least some sense of structure, Barrett was prone to perpetrating musical anarchy, regularly detuning his guitar, and frequently proving reluctant to sing. For at least one show on the Hendrix tour, he could not even be persuaded to take the stage: so it was that David O’List, The Nice’s guitarist, was cajoled into temporarily taking his place.

‘We were irritated,’ says Nick Mason. ‘There was a tendency to tut: a lot of “Oh God”. And to some extent, we ignored it. That’s the way I remember it: there wouldn’t have been a big row in the dressing-room. There was never any confrontation: it was very much, “Let’s avoid confrontation at all costs – for God’s sake, let’s try and pretend everything’s all right. Let’s not have a crisis. Maybe things will be all right if we just keep them going.” I think that’s a peculiarly English thing anyway. But we didn’t have those sorts of skills in terms of … [pause] human resources.

‘On any given night, we had no idea what was going to happen. And it wasn’t like every gig, or every song, being a disaster. I don’t remember being onstage thinking, “Here we go again.” Each time, it was a surprise.’

In the recording studio, the impossibility of Barrett’s position was increasingly evident. By way of a new single, he came up with ‘Apples and Oranges’: in Roger Waters’s view, ‘a fucking good song … destroyed by the production.’ In fact, it amounted to a loose-ended sketch that might conceivably have been honed into shape had its author not been in such a fragile state. The band’s public certainly thought as much: though EMI was desperately hoping for a third hit, ‘Apples and Oranges’ stiffed.

The run of sessions that produced that song also gave rise to three other Barrett-authored tracks, all of which attested to his decline. On ‘Jugband Blues’, a song that teetered on the brink of collapse before being suddenly and inexplicably invaded by a Salvation Army band, he came close to expressing a chronic sense of self-alienation (‘I’m not here … And I’m wondering who could be writing this song’). ‘Scream Thy Last Scream’, on which Barrett was accompanied by a speeded-up, inescapably irritating backing vocal, was eventually all but subsumed – for some reason – by a cacophony of audience noise. Perhaps most telling of all was a song called ‘Vegetable Man’. If its lyrics superficially suggested a self-deprecating joke, it also betrayed a palpable sense of self-loathing, only accentuated by the churning, discordant music that made up its backing track.

On all four songs, the sense of inspired exploration that had been the hallmark of The Piper at the Gates had evaporated. Now, it seemed, Pink Floyd were simply tumbling into chaos.

By the end of 1967, Pink Floyd (the ‘The’ would continue to crop up on posters and handbills until mid-1969, though its use was evidently on the wane) was at an unenviable career juncture. It was clear that Barrett’s role was untenable; and yet the group’s management was adamant that a future without his creative input was inconceivable. The one Roger Waters composition released thus far was ‘Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk’, a musical makeweight that amounted to Piper’s one glaring flaw; Rick Wright had contributed ‘Paintbox’, as the B-side of ‘Apples and Oranges’ – the breezy tale of a night on the town that was so lacking in any of the group’s customary experimentalism that it skirted dangerously close to the dread category of Easy Listening.

To Peter Jenner and Andrew King, all this amounted to clear evidence that Barrett had somehow to be kept in the band. Waters, however, was adamant that he had to leave. ‘Roger was the leader of the “Syd Must Go” faction,’ says Peter Jenner. ‘He was saying, “We can’t work with this guy any more. It’s impossible for us to go to a gig and have him turn up, or not turn up, and not give us a set list – it’s making us look like prats.” He was out there on the frontline, whereas I was back in the office being intellectual about it. But he was aware that they were killing their career by doing these gigs with Syd, because they were turning off the punters. It was a complete mess. And I think the worst thing was the demand for another record, when there were no songs coming from Syd. It was, “What the fuck are we going to do?” But the Syd faction – myself and Andrew – had no confidence in any of them writing without him.’

By way of a compromise, it was suggested that the group should recruit a second guitarist, leaving Barrett to appear as and when he was in sufficiently good shape, and continue to write the group’s songs. They thus made renewed contact with an old acquaintance from their days in Cambridge: David Gilmour, then making frustratingly little headway in a London-based trio called Bullitt. He accepted the offer of a new job, he later recalled, largely thanks to the prospect of ‘fame and the girls’. On the former count, at least, he did not get off to the most promising start. By the time of the announcement of his recruitment in the music press, the group’s stock had so fallen that the story was not exactly headline news: the NME gave it one small paragraph, and spelled the new member’s surname ‘Gilmur’.

In January 1968, the five-man incarnation of Pink Floyd played four shows, in Birmingham, Weston-Super-Mare, and the Sussex towns of Lewes and Hastings. Aubrey Powell clearly recalls seeing at least one of those shows, and quickly succumbing to absolute bafflement. ‘Syd wasn’t doing anything really,’ he says. ‘He was just sitting on the front of the stage, kicking his legs. It was very, very odd.’

‘My initial ambition was just to get them into some sort of shape,’ Gilmour later recalled. ‘It seems ridiculous now, but I thought the band was awfully bad at the time when I joined. The gigs I’d seen with Syd were incredibly undisciplined. The leader figure was falling apart, and so was the group.’

It did not take long for Pink Floyd to bow to the inevitable. In David Gilmour’s recollection, Barrett’s ejection from the group was confirmed as they drove from London to an engagement in Southampton. ‘Someone said, “Shall we pick up Syd?”’ he later remembered, ‘and someone else said, “Nah, let’s not bother.” And that was the end.’

So it was that Pink Floyd dispensed with the figure on whose talents their reputation had been built. ‘We carried on without a second thought,’ says Nick Mason. ‘It didn’t occur to us that it wouldn’t work. In retrospect, I find that very curious.’

CHAPTER 2

Hanging On in Quiet Desperation

Roger Waters and Pink Floyd Mark II

With Barrett gone, the creative leadership of Pink Floyd initially seemed to be up for grabs. The first recorded work they released in the wake of his exit was Rick Wright’s almost unbearably whimsical ‘It Would Be So Nice’, a single whose lightweight strain of pop-psychedelia – akin, perhaps, to the music of such faux-counterculturalists as the Hollies and Monkees – rendered it a non-event that failed to trouble the British charts; as Roger Waters later recalled, ‘No one ever heard it because it was such a lousy record.’ Waters’s own compositional efforts, however, were hardly more promising. ‘Julia Dream’, the single’s B-side, crystallized much the same problem: though the band evidently wanted to maintain the Syd Barrett aesthetic, their attempts sounded hopelessly lightweight.

As 1968 progressed, though Rick Wright continued to add songs to the group’s repertoire, it was quickly becoming clear where power now lay: with Roger Waters, the figure who, even when Barrett was around, had always had pretensions to being the band’s chief. ‘From day one, he always seemed to be the leader of the band,’ says Aubrey Powell. ‘He had a commanding presence. He could be quite brusque – rude.’

‘Roger was always the organizational person,’ says Peter Jenner. ‘If I wanted anything done, I had to fix Roger. He always had the good ideas: he always knew what he wanted to do. He was the bossy one: the one I had to persuade, always, because he could also be obstructive. He was the strongest personality in that sense.’

If such a character sketch suggests a mind with pretensions to omnipotence, Jenner also saw weaknesses in Waters’s initial contribution to the band: his apparently stunted musical talent, and his failure to satisfy the Underground’s codes of cool. ‘Roger was the worst musician,’ he says. ‘He couldn’t tune his guitar, he was tone deaf, and he also had some of the most awful sartorial things when they started becoming psychedelic. The worst thing were these red trousers that he put some dingly-dangly gold trim on, along the bottoms: the kind of thing you put on curtains. And he had a cigarette lighter in a sort of holster, dangling from his belt. He was terribly [naff], Roger. Terribly naff. But he thought he was groovy.’

Despite their friendship, the differences between Waters and Syd Barrett had tended to make them look like the occupants of completely different worlds. Barrett’s ’67-era personality was detached, non-materialistic, increasingly astral; Waters, by contrast, affected a hard-headed drive. One had become a living embodiment of sixties counterculture; the other chose to guardedly keep his distance. Perhaps most tellingly of all, whereas Barrett’s drug intake was disastrously prodigious – not simply in terms of his fondness for acid, but also when it came to marijuana and the downer Mandrax – Waters was a drinker who rarely consumed anything illicit.

‘I always remember being at the UFO club one night,’ recalls Aubrey Powell. ‘Syd was there, and Roger was there, backstage, and in walked Paul McCartney. It was a great revelatory moment: “Fuck me – a Beatle’s come to see the Pink Floyd.” Really something else. He was smoking a joint, and he passed it on. And Roger, who I’d never seen smoke before, took a huge hit of it. He knew when to play the game.’

By his own admission, Waters took acid on no more than a couple of occasions: most memorably, on a trip to Greece in 1966, with a party of friends that included Rick Wright. ‘I didn’t not do it again because I had a bad time particularly: it was more to do with how powerful it was,’ he says. ‘I’ve since heard my kids talk about taking acid and going out, and I was thinking, “Going out? You don’t go out!” Acid came out of the bottle: it was very much a case of taking your 600 milligrams or whatever and making sure that you stayed in. It was a sufficiently powerful experience that was your only option. In Greece, I took it, and thought I was coming out the other end, and went to the window in the room where I was – and I stood on the spot for another three hours [Laughs]. Just frozen.’

Waters’s onstage persona amounted to an approximation of poker-faced cool: recalling a Floyd concert at UFO in 1967, The Who’s Pete Townshend once made reference to ‘Roger Waters and his impenetrable leer’. In his early encounters with the press, he attempted to bolster the image with a hint of menace – ‘I lie and am rather aggressive,’ he told one interviewer. Underneath the hardened exterior, however, there was a good deal of fear.

‘I was that guy in the black T-shirt and jeans, standing in the corner in dark glasses, smoking cigarettes and scowling at people,’ says Waters, ‘not wanting to have anything to do with anyone, ’cos I was so frightened. I think a lot it came down to a fear of being exposed; being found out. Mainly sexual exposure, I think; I suppose a lot of it was to do with sex. Having grown up in the 1950s as an English teenager … well, there was a tremendous amount of repression hanging over all that stuff. I was far too ashamed to think about going into a barber’s shop and asking for a packet of condoms; I’d rather have died. It seems fucking ludicrous, but that’s how it was. So you had this mixture of embarrassment, and the fear of pregnancy hanging over you, and it was hard to shrug a lot of that off.’

Perhaps most importantly, whereas the story of Syd Barrett’s childhood is full of the idyllic, familial warmth reflected in such Pink Floyd songs as ‘Matilda Mother’, Waters’s upbringing had been riven by the fault-line created by the death of his father. In January 1944, Eric Fletcher Waters had been killed at Anzio, Italy, during a battle for a beachhead that lasted four months and was later described as ‘the Allies’ greatest blunder of World War II. He died aged thirty, leaving a family that had only just come into being: his wife, Mary, and two young children: Roger, five months, and an elder son named John. ‘As soon as I could talk, I was asking where my daddy was,’ Waters later reflected. ‘And my mother has often told me that when I was about two-and-a-half or three years old, it became really acute. In 1946, everyone got demobbed. Suddenly all these men appeared … they were picking their kids up from nursery school, and I became extremely agitated.’

In the long term, the death of Waters’s father seemed to foster an instinctive mistrust of authority, clearly evident during Waters’s school years. ‘I don’t necessarily know who I blamed for my father’s death: a lot of my blame was focused on the Germans; the enemy,’ he says. ‘But I think if you look at my behaviour at school, it may be that there was an element of not having a male authority figure in my home life, and therefore resisting the idea of anyone else taking on that role. That was probably a factor.’ By the time Waters became an architecture student at Regent Street Polytechnic, his irreverence had been combined with an aura of headstrong self-confidence: in the words of Nick Mason, ‘He sported an expression of scorn for the rest of us, which even the staff found off-putting.’

The details of Waters’s father’s military service lent his story a particularly tragic aspect. In the early years of World War II, Eric Fletcher Waters’s Christianity led him into conscientious objection, meaning that he was exempted from active service and given a job as an ambulance driver. As the war went on, however, he was drawn towards left-wing politics – and, eventually, the British Communist Party. Given the avowed opposition of communists to fascism, he performed a volte-face and joined the army as an officer; in that sense, his newfound political outlook cost him his life. ‘To have had the courage to not go – and then to change your mind and have the courage to go … is a sort of mysteriously heroic thing to have done,’ Waters later reflected.

In the years following the war, Mary Waters remained a communist, until the unforeseen events that caused thousands of Western European communists to renounce the party. ‘My mother lasted until 1956, when the Russians invaded Hungary,’ says Waters. ‘I don’t remember that myself, but I became aware of it later on. That was a breaking-point for a lot of people. But she was very hostile towards America. Not Americans themselves: she spent time in the USA when she was young and said that she had a tremendous amount of empathy with the people she met – but America’s economic system and their role in the world.