The Grand Tour: Letters and photographs from the British Empire Expedition 1922

We thought about it, and thought about it.

‘Of course – you could go,’ I said, bracing myself to be unselfish, ‘and I stay behind.’

I looked at him. He looked at me.

‘I’m not going to leave you behind,’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t enjoy it if I did that. No, either you risk it and come too, or not – but it’s up to you, because you risk more than I do, really.’

So again we sat and thought, and I adopted Archie’s point of view.

‘I think you’re right,’ I said. ‘It’s our chance. If we don’t do it we shall always be mad with ourselves. No, as you say, if you can’t take the risk of doing something you want, when the chance comes, life isn’t worth living.’

We had never been people who played safe. We had persisted in marrying against all opposition, and now we were determined to see the world and risk what would happen on our return.

Our home arrangements were not difficult. The Addison Mansions flat could be let advantageously, and that would pay Jessie’s wages. My mother and my sister were delighted to have Rosalind and Nurse. The only opposition of any kind came at the last moment, when we learnt that my brother Monty was coming home on leave from Africa. My sister was outraged that I was not going to stay in England for his visit.

‘Your only brother, coming back after being wounded in the war, and having been away for years, and you choose to go off round the world at that moment. I think it’s disgraceful. You ought to put your brother first.’

‘Well, I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘I ought to put my husband first. He is going on this trip and I’m going with him. Wives should go with their husbands.’

‘Monty’s your only brother, and it’s your only chance of seeing him, perhaps for years more.’

She quite upset me in the end; but my mother was strongly on my side. ‘A wife’s duty is to go with her husband,’ she said. ‘A husband must come first, even before your children – and a brother is further away still. Remember, if you’re not with your husband, if you leave him too much, you’ll lose him. That’s specially true of a man like Archie.’

‘I’m sure that’s not so,’ I said indignantly. ‘Archie is the most faithful person in the world.’

‘You never know with any man,’ said my mother, speaking in a true Victorian spirit. ‘A wife ought to be with her husband – and if she isn’t, then he feels he has a right to forget her.’

AGATHA CHRISTIE

from An Autobiography

SETTING OFF

Going round the world was one of the most exciting things that ever happened to me. It was so exciting that I could not believe it was true. I kept repeating to myself, ‘I am going round the world.’ The highlight, of course, was the thought of our holiday in Honolulu. That I should go to a South Sea island was beyond my wildest dream. It is hard for anyone to realise how one felt then, only knowing what happens nowadays. Cruises, and tours abroad, are a matter of course. They are arranged reasonably cheaply, and almost anyone appears to be able to manage one in the end.

When Archie and I had gone to stay in the Pyrenees, we had travelled second-class, sitting up all night. (Third class on foreign railways was considered to be much the same as steerage on a boat. Indeed, even in England, ladies travelling alone would never have travelled third class. Bugs, lice, and drunken men were the least to be expected if you did so, according to Grannie. Even ladies’ maids always travelled second.) We had walked from place to place in the Pyrenees and stayed at cheap hotels. We doubted afterwards whether we would be able to afford it the following year.

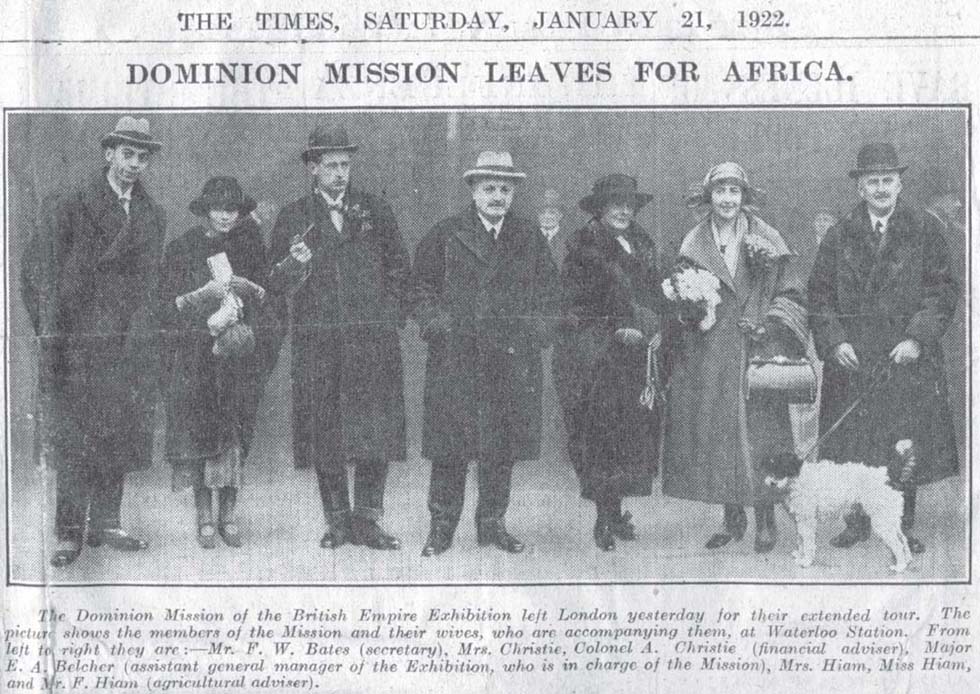

The first newspaper cutting from Agatha’s photo album. The Times caption mistakes Miss Hiam for Mrs Christie.

Now there loomed before us a luxury tour indeed. Belcher, naturally, had arranged to do everything in first-class style. Nothing but the best was good enough for the British Empire Exhibition Mission. We were what would be termed nowadays V.I.P.s, one and all.

Mr Bates, Belcher’s secretary, was a serious and credulous young man. He was an excellent secretary, but had the appearance of a villain in a melodrama, with black hair, flashing eyes and an altogether sinister aspect.

‘Looks the complete thug, doesn’t he?’ said Belcher. ‘You’d say he was going to cut your throat any moment. Actually he is the most respectable fellow you have ever known.’

Before we reached Cape Town we wondered how on earth Bates could stand being Belcher’s secretary. He was unceasingly bullied, made to work at any hour of the day or night Belcher felt like it, and developed films, took dictation, wrote and re-wrote the letters that Belcher altered the whole time. I presume he got a good salary – nothing else would have made it worth while, I am sure, especially since he had no particular love of travel. Indeed he was highly nervous in foreign parts – mainly about snakes, which he was convinced we would encounter in large quantities in every country we went to. They would be waiting particularly to attack him.

Although we started out in such high spirits, my enjoyment at least was immediately cut short. The weather was atrocious. On board the Kildonan Castle everything seemed perfect until the sea took charge. The Bay of Biscay was at its worst. I lay in my cabin groaning with sea-sickness. For four days I was prostrate, unable to keep a thing down. In the end Archie got the ship’s doctor to have a look at me. I don’t think the doctor had ever taken sea-sickness seriously. He gave me something which ‘might quieten things down,’ he said, but as it came up as soon as it got inside my stomach it was unable to do me much good. I continued to groan and feel like death, and indeed look like death; for a woman in a cabin not far from mine, having caught a few glimpses of me through the open door, asked the stewardess with great interest: ‘Is the lady in the cabin opposite dead yet?’ I spoke seriously to Archie one evening. ‘When we get to Madeira,’ I said, ‘if I am still alive, I am going to get off this boat.’

‘Oh I expect you’ll feel better soon.’

‘No, I shall never feel better. I must get offthis boat. I must get on dry land.’

‘You’ll still have to get back to England,’ he pointed out, ‘even if you did get off in Madeira.’

‘I needn’t,’ I said, ‘I could stay there. I could do some work there.’

‘What work?’ asked Archie, disbelievingly.

It was true that in those days employment for women was in short supply. Women were daughters to be supported, or wives to be supported, or widows to exist on what their husbands had left or their relations could provide. They could be companions to old ladies, or they could go as nursery governesses to children. However, I had an answer to that objection. ‘I could be a parlour-maid,’ I said. ‘I would quite like to be a parlour-maid.’

Parlour-maids were always needed, especially if they were tall. A tall parlour-maid never had any difficulty in finding a jobs – read that delightful book of Margery Sharp’s, Cluny Brown – and I was quite sure that I was well enough qualified. I knew what wine glasses to put on the table. I could open and shut the front door. I could clean the silver – we always cleaned our own silver photograph frames and bric-à-brac at home – and I could wait at table reasonably well. ‘Yes,’ I said faintly, ‘I could be a parlour-maid.’

‘Well, we’ll see,’ said Archie, ‘when we get to Madeira.’

However, by the time we arrived I was so weak that I couldn’t even contemplate getting off the bed. In fact I now felt that the only solution was to remain on the boat and die within the next day or two. After the boat had been in Madeira about five or six hours, however, I suddenly felt a good deal better. The next morning out from Madeira dawned bright and sunny, and the sea was calm. I wondered, as one does with sea-sickness, what on earth I had been making such a fuss about. After all, there was nothing the matter with me really, I had just been sea-sick.

There is no gap in the world as complete as that between one who is sea-sick and one who is not. Neither can understand the state of the other. I was never really to get my sea-legs. Everyone always assured me that after you got through the first few days you were all right. It was not true. Whenever it was rough again I felt ill, particularly if the boat pitched – but since on our cruise it was mostly fair weather, I had a happy time.

Agatha on board the Kildonan Castle.

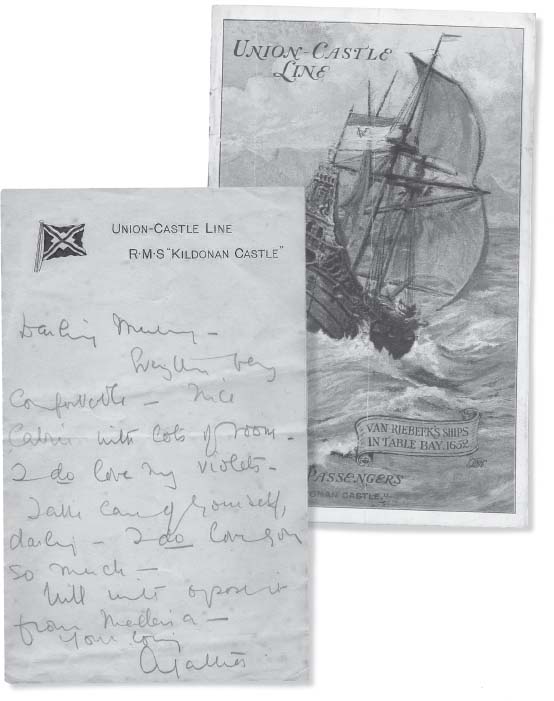

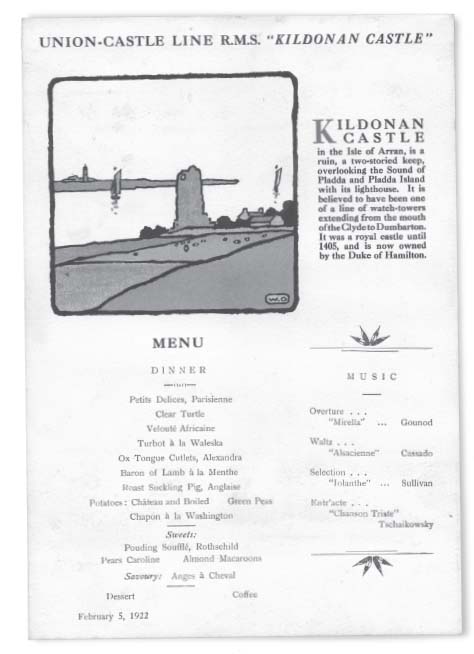

The R.M.S Kildonan Castle sailed via Madeira for Capetown, Angola, East London and Natal from Southampton on the 20th January 1922.

UNION-CASTLE LINE R.M.S ‘KILDONAN CASTLE’

First day: 20 January 1922

Darling mummy

Everything very comfortable – nice cabin with lots of room. I do love my violets. Take care of yourself, darling – I do love you so much.

Will write again from Madeira.

Your loving

Agatha

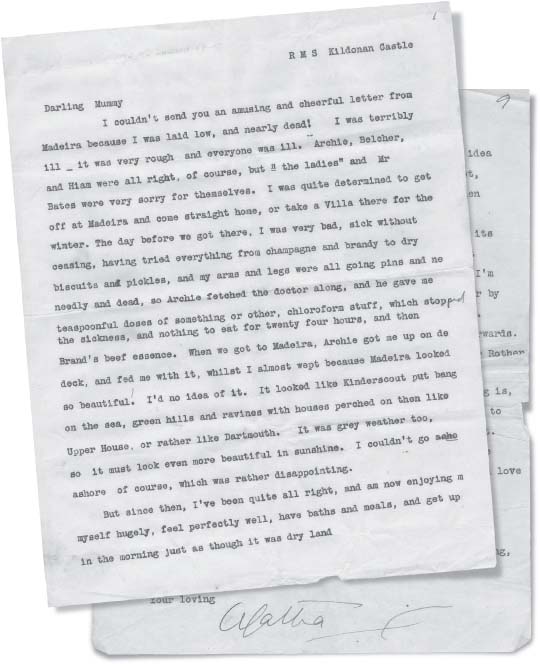

R.M.S KILDONAN CASTLE

[undated]

Darling Mummy,

I couldn’t send you an amusing and cheerful letter from Madeira because I was laid low, and nearly dead! I was terribly ill – it was very rough and everyone was ill. Archie, Belcher, and Hiam were all right, of course but ‘the ladies’ and Mr Bates were very sorry for themselves. I was quite determined to get off at Madeira and come straight home, or take a Villa there for the winter. The day before we got there, I was very bad. Sick without ceasing, having tried everything from champagne and brandy to dry biscuits and pickles, and my arms and legs were all going pins and needly and dead, so Archie fetched the doctor along, and he gave me teaspoonful doses of something or other, chloroform stuff, which stopped the sickness, and nothing to eat for twenty four hours, and then Brand’s beef essence. When we got to Madeira, Archie got me up on deck, and fed me with it, whilst I almost wept because Madeira looked so beautiful! I’d no idea of it. It looked like Kinderscout put bang on the sea, green hills and ravines with houses perched on them like Upper House, or rather like Dartmouth. It was grey weather too, so it must look even more beautiful in sunshine. I couldn’t go ashore of course, which was rather disappointing.

But since then, I’ve been quite all right, and am now enjoying myself hugely, feel perfectly well, have baths and meals, and get up in the morning just as though it was dry land.

From henceforth I shall write you a kind of diary, a little every day. I need hardly say that Belcher was at once made chairman of the Sports Committee on board. The boat is not very full. There is rather a nice sailor lad called Ashby going out to join a ship at Cape Town, who went with Mrs Tweedale over the haunted house in Torquay, a delightful woman, Miss Wright, belonging to some college out in South Africa who is most amusing, a Miss Gold who is the thinnest girl I have ever seen and like a Botticelli Madonna, and a particularly fat fellow called Samels with a very nice wife and kiddies. He’s a great ostrich person, and the Mission is fixing up a meeting with him out there. We have trained the Chief Engineer, at whose table we sit, to drink ‘Success to the Mission’ every night, which he does, murmuring. ‘But I’m still not sure what kind of a mission it is. They say it’s not religious.’

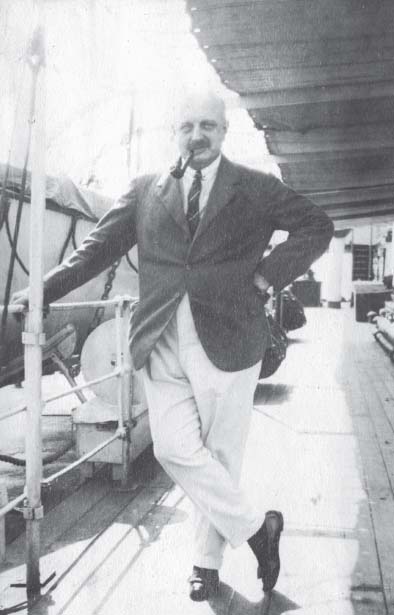

‘Our Major Belcher.’

The Hiams are nice, but dull. Won’t do anything – enter for quoits or take part in things. Archie and I entered bravely for everything, had our first contest yesterday, when to our utter surprise, we knocked out two Belgians who have infuriated the ship by hanging on to the quoits and practising all day long. It was a most popular victory. Everyone kept coming up to us and saying ‘I hear you’ve knocked out the Dagoes! Splendid.’

Belcher gave us a screaming description of his visit to the King. Whilst airily chatting to Wigram on arrival, a super footman approached and murmured ‘which links would you wish to wear this evening sir?’ ‘Oh any links, any links,’ said Belcher, to which the footman hissed in an agitated whisper: ‘I can’t find any.’ ‘And then, of course, I had to take the brass ones out of the shirt I was wearing and hand them to him. Most unfortunate!’ The King was charming and most natural, and the Queen had a full description of all the ladies accompanying the Mission, and made a note of my book. Princess Mary was not at all a dump, but very jolly, but Lascelles was a dull dog, who said little, and drank champagne in enormous quantities! They talked a good deal about ‘their boy’. The Queen said ‘My boy has had thirty five wooden caskets presented to him when he was in Australia, and of course he doesn’t know what to do with them. Lovely wood, but hideously made.’ The King told a story of Hughes starting out to drive with the Prince through Sydney. ‘He started in a topper, but when they got to the suburbs, he hid it under the seat and produced a bowler, and by the time they got to the slums be was wearing a check cap!’ He spoke very warmly of Smuts, and said Belcher reminded him of Redmond, and that Ireland would not be in the state it was if Redmond had lived. Two braces of pheasants were presented to Belcher on leaving, and we ate them on board last night, served with great éclat and ceremony!

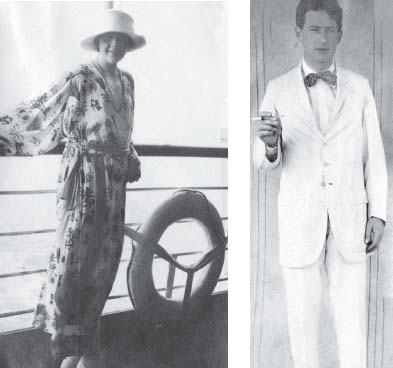

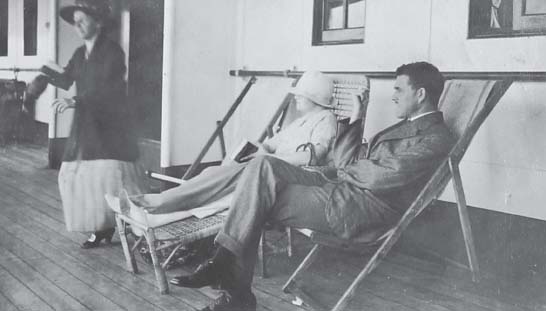

Agatha, and Archie in his tropical suit.

Aboard ship.

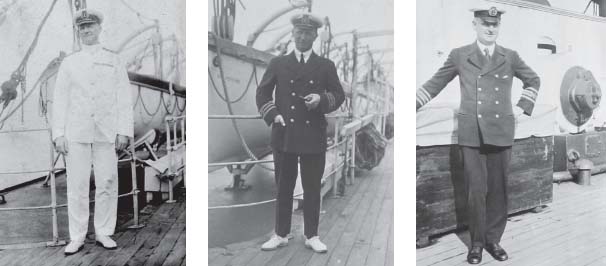

Captain Sir Benjamin Chave KBE (far left), Chief Officer Mr D. Nicoll and Chief Engineer Mr A. Munro.

Very hot now and lots of porpoises leaping, and I’ve just seen a flying fish! We passed the Grand Peak of Tenerife on Wednesday, and saw the Cape Verde lights last night. No more land now until Cape Town.

Saturday [February 4]

We had the children’s Sports today, and I was asked to give away the prizes, an honour procured for me by Belcher, as against the rival claims of Mrs Blake (wife of the Captain of the Queen Elizabeth) B. pointing out that I was of equal rank, being the wife of a Colonel in the Army, and had taken some interest in the Sports, Mrs Blake having taken none! She looks very amusing, spends all day talking to a long lean brown Commissioner for Nyasaland. I shall talk to her soon because I like the look of her.

Mrs Blake.

Mr Hiam and Mr Samels had a long and mysterious discussion on pigskin last night, H. declaring there was no such thing, S. saying there was, and that he would show him the skins, to which H. countered by saying ‘Ah, but can you show me a pig being skinned,’ and S. climbed down, and said he could not say more before the ladies. I had no idea pig skin was such a delicate subject. It seems to rank with bech de mer!

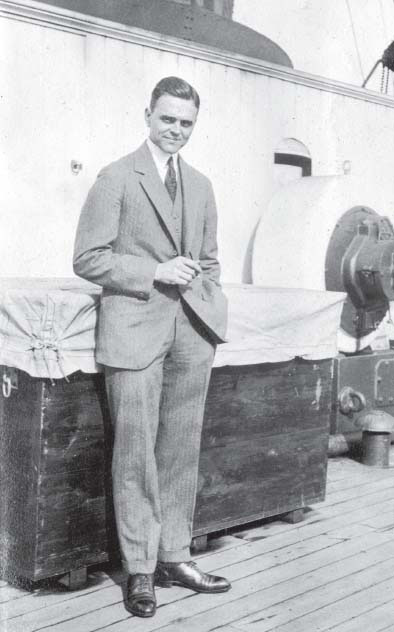

Mr Edge.

We’ve had several Bridge fours with Samels. It always takes a least three hours to finish a rubber, because he and Belcher never stop overcalling their hands, and doubling. On the whole Belcher pushes Samels a little further than Samels pushes Belcher! S. has promised me something very choice in ostrich feathers if we come to Port Elizabeth. I am now waiting for someone to ask me if I like diamonds or gold nuggets!

Mr Mayne.

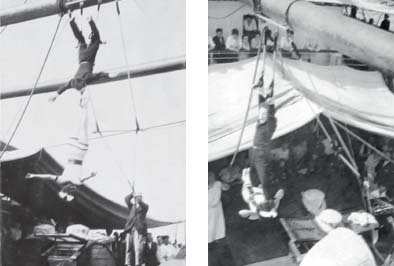

Jack and Betty, the Aerial Sensation perform on the After Deck.

There are some Dutch people, the Fichardts, I believe she was a daughter of President Stein, and they are violently anti-English. Belcher spent a whole evening talking to them last night, and this morning is writing the result in his Diary, and sending an ‘Extract’ to the King! We are sending a wedding present to Princess Mary from South Africa, and he has promised the Queen an Album of photos of the Mission and its doings!

There is a Mr Edge on board, a rich elderly bachelor, who takes thousands of photos all day long. He has made nine voyages to the Cape and back, never lands – just likes the trip.

The great daily excitement, of course is the ‘sweep’ on the day’s run. 1/ tickets, and if you draw a number, it is most thrilling. I’ve drawn a number nearly every day. My one today was a good one, and sold in the Auction for a pound. Not fancying my luck, I’ve never bought one in so far, but let them go for what they’d fetch – luckily as it proves, but Archie bought his in yesterday for 25/ and got second – £5 15/! Belcher, by common acclamation, is always auctioneer, with Samels (in a terrible green and white striped shirt!) as clown of the piece, and there is a little American called Mayne who does most of the bidding. He is rather nice, dances beautifully, and deals in ‘grain elevators’ (as much of a mystery to me as ‘filled cheese’ was to you). We had a fancy dress dance last night, and he was very serious about his costume. ‘I have a costume, period 1840, and a costume, period 1830, and a costume 1820!’ In the end, the preference was given to the 1840. My Bacchante was quite a success, and Belcher hired a marvellous Chu Chin Chow costume from the Barber, suitable to his bulk, and looked simply screaming – in fact won 1st prize.

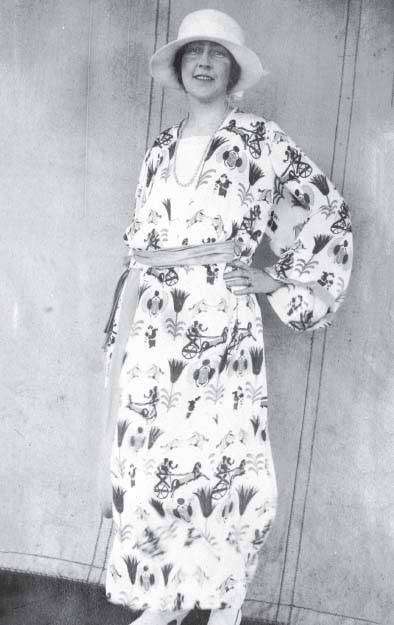

Agatha in her ‘Chariots and Horses’ outfit.

Mrs Blake and Mr Murray.

Of course it has been very hot the last few days, passing over the line [Equator]. I haven’t minded it. We’ve got a big electric fan in the cabin, and I wrested the top bunk from Archie, and we sleep with no clothes on, and trust to Providence to wake up in the morning before the steward comes in! But the heat nearly kills poor Mrs Hiam. It’s getting cooler again now.

With a lot of pushing, Sylvia Hiam is ‘getting off’ with young Ashby. He’s such a nice boy, and she’s the only young thing on the ship, but although very pretty, is a terrible mutt.

I have succeeded in talking to Mrs Blake, and find her most amusing. She dined at our table on the occasion of the last brace of the King’s pheasants! Mr Murray, the commissioner, is very nice too. She is going to the Mount Nelson Hotel also, to be about three weeks with her father, who lives out there for his lungs, I gather. She and I have taken rather a fancy to each other.

To our intense surprise, Archie and I succeeded in winning the 2nd prize for Deck Quoits – and very nearly won the 1st prize. We selected very nice table napkin rings with the Kildonan Castle Arms on them. At one moment, I rather fancied I might win the Ladies singles, but there came against me, Mrs Fichardt, who is quite my idea of the Mother of the Gracchi, a great big fair woman, very calm, with really rather a statuesque figure built on big lines, no nerves, and about fourteen children who cluster round and urge her on in eager Dutch.

SOUTH AFRICA

My memories of Cape Town are more vivid than of other places; I suppose because it was the first real port we came to, and it was all so new and strange. Table Mountain with its queer flat shape, the sunshine, the delicious peaches, the bathing – it was all wonderful. I have never been back there – really I cannot think why. I loved it so much. We stayed at one of the best hotels, where Belcher made himself felt from the beginning. He was infuriated with the fruit served for breakfast, which was hard and unripe. ‘What do you call these?’ he roared. ‘Peaches? You could bounce them and they wouldn’t come to any harm.’ He suited his action to the word, and bounced about five unripe peaches. ‘You see?’ he said. They don’t squash. They ought to squash if they were ripe.’

It was then that I got my inkling that travelling with Belcher might not be as pleasant as it had seemed in prospect at our dinner-table in the flat a month before.

This is no travel book – only a dwelling back on those memories that stand out in my mind; times that have mattered to me, places and incidents that have enchanted me. South Africa meant a lot to me. From Cape Town the party divided. Archie, Mrs Hyam, and Sylvia went to Port Elizabeth, and were to rejoin us in Rhodesia. Belcher, Mr Hyam and I went to the diamond mines at Kimberley, on through the Matopos, to rejoin the others at Salisbury. My memory brings back to me hot dusty days in the train going north through the Karroo, being ceaselessly thirsty, and having iced lemonades. I remember a long straight line of railway in Bechuanaland. Vague thoughts come back of Belcher bullying Bates and arguing with Hyam. The Matopos I found exciting, with their great boulders piled up as though a giant had thrown them there.

Group photo at Hout’s Bay, Cape Town.

At Salisbury we had a pleasant time among happy English people, and from there Archie and I went on a quick trip to the Victoria Falls. I am glad I have never been back, so that my first memory of them remains unaffected. Great trees, soft mists of rain, its rainbow colouring, wandering through the forest with Archie, and every now and then the rainbow mist parting to show you for one tantalising second the Falls in all their glory pouring down. Yes, I put that as one of my seven wonders of the world.

We went to Livingstone and saw the crocodiles swim ming about, and the hippopotami. From the train journey I brought back carved wooden animals, held up at various stations by little native boys, asking three pence or sixpence for them. They were delightful. I still have several of them, carved in soft wood and marked, I suppose, with a hot poker: elands, giraffes, hippopotami, zebras – simple, crude, and with a great charm and grace of their own.

We went to Johannesburg, of which I have no memory at all; to Pretoria, of which I remember the golden stone of the Union Buildings; then on to Durban, which was a disappointment because one had to bathe in an enclosure, netted off from the open sea. The thing I enjoyed most, I suppose, in Cape Province, was the bathing. Whenever we could steal time off – or rather when Archie could – we took the train and went to Muizenberg, got our surf boards, and went out surfing together. The surf boards in South Africa were made of light, thin wood, easy to carry, and one soon got the knack of coming in on the waves. It was occasionally painful as you took a nose dive down into the sand, but on the whole it was easy sport and great fun. We had picnics there, sitting in the sand dunes. I remember the beautiful flowers, especially, I think, at the Bishop’s house or Palace, where we must have been to a party. There was a red gar-den, and also a blue garden with tall blue flowers. The blue garden was particularly lovely with its background of plumbago.