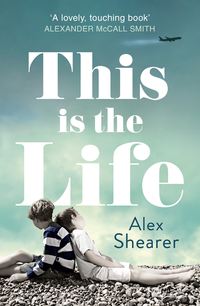

This is the Life

There was no comfort in that boat at all, just a couple of hard bunks and a stove to cook beans on.

‘It’s a doer-upper,’ Louis told me. ‘What do you think?’

‘I think,’ I told him, ‘that the trouble with you and your doer-uppers, Louis, is that you never do do them up. You never get round to it, do you? You lose interest and start on something else and you don’t finish that either. Because you lose interest again and—’

‘I’m thinking of doing it out in mahogany,’ Louis said. ‘I’ll put some partition walls up and get it divided into rooms. Bathroom here, galley there, living quarters here, guest bedroom there.’

‘Where are you putting the games room, spa and indoor swimming area, Louis?’ I asked. But he ignored me as if I hadn’t spoken.

‘It’s going to be something special once it’s done.’

‘It’ll be something special if it ever does get done. This is the story of your life to date, Louis,’ I said. ‘Things taken on and not seen through. Great projects started and never completed. Remember that astronomical telescope you were going to make when we were kids?’

‘I made a start on it but was trammelled by lack of proper equipment,’ he said.

‘Louis,’ I reminded him, ‘you were going to grind your own lenses. And the bits of glass were a yard across and six inches thick.’

‘If I was doing it today, I’d do it differently,’ Louis said.

‘Okay, Louis. If you really want my opinion – and I know you don’t – the first thing I’d do to this boat if I were you – apart from sell it – is to put a proper heating system in. Get a wood-burning stove or something. That little cooker is not going to warm this boat. Not once winter comes. It’s going to be so cold in here come January that brass will crack.’

‘We don’t need any stoves,’ Louis told me. ‘We’re tough.’

‘You may be tough,’ I said. ‘But when winter comes I’m going to buy myself a portable gas heater for the flat.’

I seem to recollect that Louis spent a lot of time that winter round at our apartment, sleeping on the sofa. He and my girlfriend Iona got on okay. But then they were both bohemians and weren’t paying any rent.

The fact was that when it came to being tough, I only really helped the tough guys out when they were busy. My parents had wanted a girl as their second child, only they hadn’t got one, they had got me. According to my mother I was born so scrawny I wasn’t expected to live, but live I did. Even now there are people who bear grudges about that. But I can’t do anything about it.

Spring came and the air got warmer and Louis went back to his boat. Sometimes the harbour master would move the boat on a whim and Louis would go home after a night in the pub to find his boat gone from its moorings, and he would have to tramp round the harbour looking for it, which could take him an hour or more. He fell in the water a few times, but it was only to be expected and was probably character-building, and it never seemed to do him any harm, apart from the difficulty he had in drying his clothes.

Looking back now, I see that was the start of his sartorial problems and when he first began aiming for the rough-sleeper look, which he seemed to so effortlessly accomplish. He ripped his trousers once and walked round for a week with the leg flapping until Iona sewed it up for him, even though she was a strong feminist and it was old-style women’s work.

‘You should be able to sew up your own trousers, Louis,’ she told him.

‘I’m working on it,’ he said.

‘I thought you were working on your boat,’ I told him.

‘I’m working on them both.’

He was actually working on neither. He had a new interest, making occasional tables.

‘Does that mean the tables are for particular occasions, Louis? Or does it mean you just make them occasionally?’

He just looked at me as if I wasn’t there and didn’t answer.

I still have one of his occasional tables, sitting right there in the dining room. Tile inlaid surface and pine legs. It’s warped and buckled a little with the passing of the years, but it’s lasted the course. It’s outlived its maker in any event. It wasn’t that Louis couldn’t do things, it was that he couldn’t make money out of them. Nor was he a natural craftsman, he was more one by ambition and willpower. He lost his temper with inanimate objects quite a lot. I could be wrong but I believe that natural craftsmen don’t do that – they know how to bend the inanimate to their will, and how to persuade it into shape with cajoling and subtlety and cunning. And that’s the craft of it.

Louis’ savings slowly dwindled and he couldn’t be a bohemian any more. He went and got a manual job assembling generators. It was just a stop-gap thing, like so many of those jobs were. He stop-gapped for almost the rest of his life. And maybe I’m wrong about his stopping being a bohemian. Maybe he was just a bohemian in a nine to five job; the bohemianism was in his soul.

He never did do the boat up, nor did he ever install a stove. He ended up hauling the boat out of the water and chopping it up for firewood.

But before that, we had a crisis.

The phone rang in the flat and it was a woman with a French-sounding accent.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘I was given this number and I want to speak to Louis.’

‘Who’s calling?’ I said.

‘Chancelle,’ she said. ‘I’m at the airport and have flown over to get back together with Louis and I want to have his babies.’

‘Who gave you my number?’

‘Your mother.’

‘I see. Well, Louis doesn’t live here, Chancelle—’ She stifled a sob. ‘That is, he lives near, but this is my place.’

‘But I have come all this way—’

‘Wouldn’t it have been better to take soundings first?’

‘What is this – take soundings?’

‘Chancelle, have you communicated with Louis about this? You haven’t seen each other in, what, three, four years? Have you written to him? Was he expecting you?’

‘I love Louis so much and want to have his babies.’

‘Well, you’ll need to speak to Louis about that. I don’t know where he stands on babies. That’s something you’ll need to discuss.’

‘I am coming to see him.’

‘Chancelle—’

‘I am getting on the bus.’

‘Chancelle, you don’t even know—’

‘Your mother gave me your address. I’ll be there tonight. Tell Louis I love him.’

The phone went dead.

‘Who was that?’ Iona said.

‘Chancelle,’ I explained. ‘Louis’ ex from Canada. She’s landed at Heathrow.’

‘What does she want?’

‘She wants to have his babies.’

Iona gave me a strange and narrow-eyed look. I didn’t know then that she wanted to have my babies. But I didn’t want any babies at that time in my life. Eventually despairing of never having any babies, Iona went off to have them with somebody else.

‘Well, is he expecting her?’

‘I don’t think he’s heard from her in years.’

I found Louis down at the docks, chewing the fat with his neighbours. Wherever you go in the world you will find men with boats chewing the fat. They rarely venture anywhere. Their boats are usually out of the water and need something doing to them. There’s some rubbing down going on, or some filling in, or they’re painting the hull in de-fouling liquid. The maintenance is long and the voyages are few. But that’s not the point. The point is the old boats and the tea and the bacon sandwiches and a place to go come the Bank Holidays and the empty vacation times and the long, hot, eternal summer days, when you can take your shirt off and let your belly hang out and show the passers-by your tattoos.

‘Louis,’ I said. ‘I just got a phone call. It’s Chancelle and she’s landed at Heathrow and she’s coming down here to have your babies.’

Louis looked panic-stricken.

‘She’s coming here?’

‘Right now. Even as we speak she’s on the bus and throwing her birth-control devices out of the window.’

‘Jesus,’ Louis said.

‘What do you want me to say?’

‘I’m going to have to go,’ Louis said. And he went on board his boat and started packing a bag. He had bought an old rusty car by now. He got it cheap as it had three hundred thousand miles on the clock.

‘Louis,’ I said, following him. ‘You can’t just disappear and leave me to deal with her. What am I going to say? She wants to have your babies.’

‘Well, I don’t want to have her babies.’

‘You what?’

He threw a grey towel into a bag.

‘That is I don’t want her to have mine. I haven’t heard from her in years. She’s crazy.’

‘I guess the separatist politics must have gone wrong.’

‘I’m not seeing her.’

‘Louis, where are you going?’

‘Walking,’ he said. ‘In Wales.’

‘Louis,’ I said. ‘You can’t just run off and disappear and leave me to deal with a woman who’s travelled six thousand miles or however far it is to have your babies.’

‘Watch me.’

‘Louis, it isn’t fair.’

He paused in packing his bag.

‘Remember the school bus? When you got arrested?’

‘Maybe, Louis. But who’s the delinquent now?’

‘Blood’s thicker,’ he said.

‘Louis—’

‘It’s your turn to do me a favour,’ he said.

‘Louis, I’ve done you favours. You’ve spent the whole winter in front of my portable gas fire and my girlfriend sewed your trousers up.’

He zipped the holdall and squared up to me. He was no taller than I was, but he was a stone or two heavier, and it wasn’t fat, it was muscle. Though when it came to a fight we were fairly equal, for though he was the stronger, I was the more desperate man. I think I had discovered that when we were children. And the reason I was more desperate and fought more ferociously was because I knew I was the weaker.

‘It’s little to ask from your only brother. It’s little to ask. I’d do it for you.’

‘You wouldn’t, Louis. You’d tell me to face up to my responsibilities.’

‘I’m going walking in the Black Mountains,’ he said. ‘I’ll be back Thursday or when she’s gone, whichever is the sooner. I’ll call.’ He hustled me out of the boat and locked it. Then he had a thought.

‘You want to come with me?’ he said. ‘You like walking, don’t you?’

‘Louis, I have to go to work. And how come you can take time off?’

‘They owe me holidays.’

‘Louis, what am I going to say to Chancelle about your babies?’

‘Tell her I had a vasectomy.’

And off he went. He had a little trouble getting the car started and almost suffocated the both of us with all the black smoke. But that was Louis for you – Louis and his vehicles. If they didn’t burn oil and belch out fumes and break down regularly, he wouldn’t buy them.

Chancelle turned up that evening and was nigh inconsolable. She had put on a lot of weight and looked as though she were expecting babies already, quite a few of them, or at the very least twins.

She sat and sobbed and sobbed, but I had to be hard and I told her it was over and there was nothing anyone could do, as Louis had gone off to the Black Mountains and he didn’t want to have babies with her at any price.

Iona held her hand and I made some tea and then we sent out for a pizza. She stayed the night on the sofa, and when I explained that Louis had spent the winter there, she seemed comforted slightly.

The next morning she got a bus to London and that was the last we saw or heard of her.

Louis rang the following evening and asked if it was safe to come home.

‘Louis,’ I said, ‘when you say “home”, where do you mean exactly?’

‘Where the heart is,’ he said.

He could throw me like that sometimes by coming out with the completely unexpected.

‘I’ve met someone,’ he said. ‘With blonde hair.’

‘What? In the Black Mountains?’

‘She’s a backpacker from New Zealand. I’ve invited her to stay on my boat for a while.’

‘I hope she doesn’t feel the cold then, Louis.’

‘No way,’ he said. ‘We’re tough.’

6

OLD BLACK DOG

It’s easy to think that you know where and when the rot started. With the so-called benefit of hindsight. Always presuming it is a benefit and not the opposite, some kind of handicap or millstone thing around your neck.

I was eleven years old and Louis was twelve and our father was dying upstairs in a room we were no longer allowed to enter on the grounds that he wanted us to remember him as he was. The flaw in this prohibition was that he hadn’t looked so great the last time we had seen him, and if I had to remember him in that condition, then I could equally have remembered him in his last few days and been no more the traumatised.

He’d been suffering from lung cancer due to twenty to thirty a day hand-rolled for years and years.

Whenever I see these tobacco company executives in their nice suits and white shirts and sober ties, as they make their justifications and announce their profits and explain how they are opening up fresh markets in the new world, I think the sons-of-bitches should be boiled in oil for all the suffering they have caused. And I wonder if they smoke, or if they would want their own children to smoke, and I firmly believe it’s the last thing they would want, to find their own offspring hanging out of the bathroom window with cigarettes in their mouths.

Anyway, he spent his last few weeks getting increasingly yellow and burning holes in the sheets to our mother’s fear and dismay, for he carried on smoking right to the bitter end – and it was bitter. She was afraid he’d set fire to the bed and the whole place would go up, and then we’d all die of smoke inhalation together.

So it wasn’t a question of if, just when. And I came home from school one afternoon to find Louis waiting at the back of the house. For the front door was a thing we never used except for visitors, or when the police came round to talk about the rhododendron bush.

Louis had been waiting for me to return, for though we were at the same school, we were in different classes, and he always took the high road home, whereas I took the low road, with its many distractions, and so I rarely got back before him.

‘He’s dead,’ Louis told me.

I shrugged, for we were tough.

‘That so?’ I said.

And we stood there a while, and then we went inside, and our mother was in the kitchen, and the rest is pretty much of a blank.

After the funeral we came home, the three of us, to our sad, shabby, rented home. I wouldn’t say it reeked of poverty, but there was certainly an odour of the stuff around the place and opening the windows and letting the air in didn’t ever make a huge amount of difference.

Our mother began taking her best and only jacket off and starting in on the tea-making, which was her recourse in all contingencies.

‘Well, Louis,’ she said. ‘I guess that you’re the man of the house now.’

I don’t blame her for what she said in her grief and loneliness, but to this day I’m convinced it was the beginning of at least half of the trouble. It’s a hard job to have to take on, being the man of the place at twelve years old. But Louis had to shoulder the burden. The corollary of that, of course, was all the resentment it created in me. I bit my lip and kept my mouth shut, but inside my heart was boiling, and I thought no way is my brother going to be my father, and I was stubborn ever after, and went to the bad for a while, and took up attacking rhododendron bushes.

What brought it all back to mind was when I first got to Louis’ place in Australia and walked in through the door and saw him in his beanie hat with a quarter of his mind gone and the next thing I saw was his kettle – which deserves a digression of its own at another time – and I clapped my eyes on his fridge.

There were things living in that fridge that even medical science didn’t know about. Its age was incalculable. They didn’t make fridges like that any more. Maybe they never had and Louis had constructed it himself out of old spare parts and tree bark.

But it wasn’t just the mould, the grime, the gone-off food, the brown grapefruit, the rust, the smell and all the rest. It was the fridge magnets. There were half a dozen of them, all of them rusty too, and they bore messages saying: Depression – you are not alone. And they had phone numbers on them of people you could call and could talk to. But whether Louis had ever called and spoken to anyone, I never asked. I just thought that well, the old black dog was back, or maybe it had never gone away. I knew that Louis had always had it snapping at his heels. But maybe it had got him by the throat lately, or even now was hiding in the house somewhere, under the bed in the deep, deep dust, or growling down in the basement. Or maybe that was it making noises up in the loft. Only when I later asked Louis about the loft noises that were keeping me awake, he said it was possums.

So I asked why he didn’t get rid of them, but he said they didn’t bother him too much, so maybe he liked their company. I asked him what they were doing up there that made so much noise.

‘They’re having a root,’ he said. ‘They’re rooting away, making more possums.’

‘Louis,’ I said. ‘What use are even more possums to you? You can’t even cope with the ones you already have.’

But he just shrugged and wouldn’t do anything about them. And I didn’t want to buy poison or anything, for I drew the line at poisoning possums, though had it been rats, I wouldn’t have thought twice. So we just had to put up with the racket, but it left you feeling tired in the mornings, and maybe it made the possums feel tired too.

‘Why can’t they have a root before they go to sleep, Louis?’

‘That’s how they are,’ he said.

‘But you know what it’s like when you wake up in the morning when there’s two of you.’

‘Farts and bad breath and stale alcohol,’ Louis said, for he was always one to cut to the chase and never mind the niceties. ‘But you do it anyway. Though in a possum’s case, there maybe isn’t the stale alcohol.’

‘Louis,’ I said. ‘Are you all right?’

And I meant regarding the fridge stickers. But some things, even when we reached out for them, we never really grabbed hold of. You know that famous painting, in the Sistine Chapel, called ‘The Creation’, with God and Man reaching out for each other but their hands don’t quite connect. That was how we communicated.

‘Let’s have a drink,’ Louis said.

‘What do you want?’

‘Cuppa tea,’ he said.

‘All right. Sit down and I’ll make us one.’

That was when I noticed the kettle.

‘Louis,’ I said. ‘What’s the deal with the kettle?’

‘What do you mean?’ he said. ‘What’s wrong with it?’

Louis lived inside but really he was camping out.

On his grease- and left-overs-encrusted gas stove stood a blackened kettle. It was one of the old-fashioned kind that you boil over a hob. Louis did have electricity, but it didn’t extend as far as his hot drink requirements.

‘Louis,’ I said. ‘This kettle has no handle.’

‘Broken off,’ he said.

‘Louis, when did the handle break off?’

He gave another of his shrugs. He had square, solid, powerful shoulders. If you’d been thinking of a fight with him, you’d think twice.

‘I don’t know. Few years ago.’

He went and sat in his Salvation Army armchair and opened up his blue cooler bag and fished out some eye drops for his glaucoma.

‘Louis, how do you pour the water out when the kettle has boiled?’

‘Tea towel,’ he said, with annoyance in his voice, as if I was being deliberately obtuse.

‘So let me get this right, Louis. You have lived for unspecified years with a kettle with no handle that you have to wrap a tea towel around to pour the water out of?’

‘I’m doing my eyes!’

‘Louis, how much is a kettle?’

‘I’ve been busy.’

‘I’m going to buy one tomorrow.’

‘Don’t waste your money.’

‘Louis, a kettle with a handle will make life easier, right? If you make your own life easier, you’re not wasting your money. You’re just spending it on improving your situation, right?’

‘We don’t need handles on our kettles, we’re—’

‘Louis, not having a handle on your kettle doesn’t make you tough. Being tough has nothing to do with kettle handles. Scott of the Antarctic went to the South Pole, Louis. Was he tough?’

‘You’d need to ask him.’

‘Louis, I’ve seen pictures of Scott of the Antarctic and his men in their hut at the South Pole and I swear to God, Louis, that they had a handle on their kettle. They might even have carried a spare handle, for all I know.’

‘Are you making the tea or aren’t you?’

So I made the tea. I had to scour the mugs first. They were stained a deep tannin brown inside.

‘There you go.’

‘Thanks.’

‘I’m buying a new kettle tomorrow, Louis. While you’re at the hospital, I’m buying a new kettle.’

‘Don’t waste your money.’

But I didn’t listen to him and I did what I wanted. Who did he think he was anyway? My father or someone?

We ended up with two new kettles. One electric, and one for the gas stove – with a handle. I edged the old one out of the house gradually. First I left it out on the veranda. Then, when Louis didn’t notice that, I carried it down the stairs and left it in the garden. After a week I moved it next to the bin. The following week I put it in the bin. Then, on the Tuesday, I put the bin out for collection.

On Wednesday, when Louis was back from his radiotherapy, he began mooching around the kitchen.

‘You lost something, Louis?’ I asked.

‘My kettle,’ he said. ‘Where’s my kettle?’

‘Right there,’ I said, pointing at the electric one plugged into the wall. ‘Or did you mean this one?’ And there was the new and shiny blue one on the gas hob.

‘No. My kettle. My kettle.’

‘You mean the old burnt black and crusty one with no handle?’

‘My kettle.’

‘Louis, I didn’t think you wanted it any more. I didn’t think we needed it. As we have these nice new kettles. So I’m afraid – it’s gone.’

‘You threw it out? You threw out my kettle?’

‘Louis, it was dangerous, you could have scalded yourself, or set fire to the place, you had to wrap a tea towel around it. It was a liability.’

He just looked at me through his milky eyes, now filled with infinite reproach, and I felt like some kind of murderer for what I had done.

‘Louis, I didn’t know it meant that much to you. I thought it was just an old kettle.’

Without another word, he turned his back on me, and he went to his room and lay down on his bed. The mix of chemo and radiotherapy was very tiring and he spent a lot of the day asleep.

I felt bad. I realised what I had done. It was part of Louis I had thrown away. For years Louis had been the man with the kettle with no handle. People had come round and he had made them a coffee or a tea or a herbal something. And he had poured out their drinks, first carefully wrapping the dirty, scorched old tea towel around the body of the kettle. And they’d watched him do so, and everyone knew that Louis was the man with the kettle without a handle. And so it had been for many years. There had been talk and conversation and many a long hour of putting the world to rights, there in that choked and cluttered kitchen that had seen neither floor cloth nor mop for a decade.

But that had been Louis. That had been part of who he was.

‘You know, Louis, don’t you? The guy with the beard and the kettle.’

Now he only had the beard left and that had been to the barber’s.

I felt bad, like a tyrant, like one who had taken advantage of vulnerabilities. But I couldn’t bring the kettle back. It had gone to the dump and even if I searched I would never find it. It was there with all the other long-gone and inadequate domestic appliances. True, I had bought him a new one, but what use was new when it wasn’t what you loved?

I don’t have much advice to give anyone; I’ve learned very little in my life; but here’s my gem of wisdom. Don’t take a dying man’s kettle away. You won’t be doing him any favours. Nor yourself either.