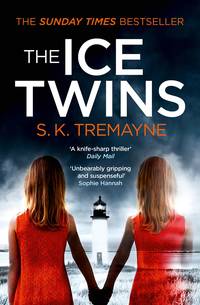

The Ice Twins

I want these drowning feelings to stop.

‘Mummyyy?’

Angus and I share a resigned glance: both of us mentally calculating the last time this happened. Like two very new parents squabbling over whose turn it is to baby-feed, at three a.m.

‘I’ll go,’ I say. ‘It’s my turn.’

And it is: the last time Kirstie woke up, after one of her nightmares, was just a few days ago, and Angus had loyally traipsed upstairs to do the comforting.

Setting down my wine glass, I head for the first floor. Beany is following me, eagerly, as if we are going rabbiting; his tail whips against the table legs.

Kirstie is barefoot, at the top of the stairs. She is the image of troubled innocence with her big blue eyes, and with Leopardy pressed to her buttoned pyjama-top.

‘It did it again, Mummy, the dream.’

‘Come on, Moomin. It’s just a bad dream.’

I pick her up – she is almost too heavy, these days – and carry her back into the bedroom. Kirstie is, it seems, not too badly flustered; though I wish this repetitive nightmare would stop. As I tuck her in her bed, again, she is already half-closing her eyes, even as she talks.

‘It was all white, Mummy, all around me, I was stuck in a room, all white, all faces staring at me.’

‘Shhhhh.’

‘It was white and I was scared and I couldn’t move then and then … then …’

‘Shushhh.’

I stroke her faintly fevered, blemishless forehead. Her eyelids flicker towards sleep. But a whimpering, from behind me, stirs her.

The dog has followed me into the bedroom.

Kirstie searches my face for a favour.

‘Can Beany stay with me, Mummy? Can he sleep in my room tonight?’

I don’t normally allow this. But tonight I just want to go back downstairs, and drink another glass, with Immy and Angus.

‘All right, Sawney Bean can stay, just this once.’

‘Beany!’ Kirstie leans up from her pillow, and reaches a little hand and jiggles the dog’s ears.

I stare at my daughter, meaningfully.

‘Thuh?’

‘Thank you, Mummy.’

‘Good. Now you must go back to sleep. School tomorrow.’

She hasn’t called herself ‘we’, she hasn’t called herself ‘Lydia’. This is a serious relief. When she settles her head on the cool pillow I walk to the door.

But as I back away, my eyes fix on the dog.

He is lying by Kirstie’s bed, and his head is meekly tilted, ready for sleep.

And now the sense of dread returns. Because I’ve worked it out: what was troubling me. The dog. The dog is behaving differently.

From the day we bought Beany home to our ecstatic little girls, his relationship with the twins was marked – yet it was, also, differentiated. My twins might have been identical, but Sawney did not love them identically.

With Kirstie, the first twin, the buoyant twin, the surviving twin, the leader of mischief, the girl sleeping in this bed, right now, in this room, Beany is extrovert: jumping up at her when she gets home from school, chasing her playfully down the hall – making her scream in delighted terror.

With Lydia, the quieter twin, the more soulful twin, the twin that used to sit and read with me for hours, the twin that fell to her death last year, our spaniel was always gentle, as if sensing her more vulnerable personality. He would nuzzle her, and press his paws on her lap: amiable and warm.

And Sawney Bean also liked to sleep in Lydia’s room if he could, even though we usually chased him out; and when he did come in to her room, he would lie by her bed at night, and tilt his head, meekly.

As he is doing now, with Kirstie.

I stare at my hands; they have a fine tremor. The anxiety is like pins and needles.

Because Beany is not extrovert with Kirstie any more. He behaves with Kirstie exactly as he used to with Lydia.

Gentle. Nuzzling. Soft.

The self-questioning surges. When did the dog’s behaviour change? Right after Lydia’s death? Later?

I strive, but I cannot remember. The last year has been a blur of grief: so much has altered I have paid no attention to the dog. So what has happened? Is it possible the dog is, somehow, grieving? Can an animal mourn? Or is it something else, something worse?

I have to investigate this: I can’t let it lie. Quickly I exit Kirstie’s room, leaving her to her reassuring nightlight; then I pace five yards to the next door. Lydia’s old room.

We have transformed Lydia’s room into an office space: trying, unsuccessfully, to erase the memories with work. The walls are lined with books, mostly mine. And plenty of them – at least half a shelf – are about twins.

When I was pregnant I read every book I could find on this subject. It’s the way I process things: I read about them. So I read books on the problems of twin prematurity, books on the problems on twin individuation, books that told me how a twin is more closely related, genetically, to her co-twin, to her twin sibling, than she is to her parents, or even her own children.

And I also read something about twins and dogs. I am sure.

Urgently I search the shelves. This one? No. This one? Yes.

Pulling down the book – Multiple Births: A Practical Guide – I flick hurriedly to the index.

Dogs, page 187.

And here it is. This is the paragraph I remembered.

Identical twins can sometimes be difficult to physically differentiate, well into their teenage years – even, on occasion, for their parents. Curiously, however, dogs do not have the same difficulty. Such is the canine sense of smell, a dog – a family pet, for instance – can, after a few weeks, permanently differentiate between one twin and another, by scent alone.

The book rests in my hands; but my eyes are staring into the total blackness of the uncurtained window. Piecing together the evidence.

Kirstie’s personality has become quieter, shyer, more reserved, this last year. More like Lydia’s. Until now I had ascribed this to grief. After all, everyone has changed this last year.

But what if we have made a terrible mistake? The most terrible mistake imaginable? How would we unravel it? What could we do? What would it do to all of us? I know one thing: I cannot tell my fractured husband any of this. I cannot tell anyone. There is no point in dropping this bomb. Not until I am sure. But how do I prove this, one way or another?

Dry-mouthed and anxious, I walk out onto the landing. I stare at the door. And those words written in spangled, cut-out paper letters.

Kirstie Lives Here.

3

I once read a survey that explained how moving house is as traumatic as a divorce, or as the death of a parent. I feel the opposite: for the two weeks after our meeting with Walker – for the two weeks after Kirstie said what she said – I am fiercely pleased that we are moving house, because it means I am overworked and, at least sometimes, distracted.

I like the thirst-inducing weariness in my arms as I lift cases from lofty cupboards, I like the tang of old dust in my mouth as I empty and scour the endless bookshelves.

But the doubts will not be entirely silenced. At least once a day I compare the history of the twins’ upbringing with the details of Lydia’s death. Is it possible, could it be possible, that we misidentified the daughter we lost?

I don’t know. And so I am stalling. For the last two weeks whenever I’ve dropped Kirstie off at school, I’ve called her ‘darling’ and ‘Moomin’ and anything-but-her-real-name, because I am scared she will turn and give me her tranced, passive, blue-eyed stare and say I’m Lydia. Not Kirstie. Kirstie is dead. One of us is dead. We’re dead. I’m alive. I’m Lydia. How could you get that wrong, Mummy? How did you do that? How?

And after that I get to work, to stop myself thinking.

Today I am tackling the toughest job. As Angus has left, on an early flight to Scotland, preparing the way, and as Kirstie is in school – Kirstie Jane Kerrera Moorcroft – I am going to sort the loft. Where we keep what is left of Lydia. Lydia May Tanera Moorcroft.

Standing under the hinged wooden trapdoor, I position the unfeasibly light aluminium stepladder, and pause. Helpless. Thinking again.

Start from the beginning, Sarah Moorcroft. Work it out.

Kirstie and Lydia.

We gave the twins different-but-related names because we wanted to emphasize their individuality, yet acknowledge their unique twin status: just as all the books and websites advised. Kirstie was named thus by her dad, as it was his beloved grandmother’s name. Scottish, sweet, and lyrical.

By way of equity, I was allowed to choose Lydia’s name. I made it classical, indeed ancient Greek. Lydia. I chose this partly because I love history, and partly because I am very fond of the name Lydia, and partly because it was not like Kirstie at all.

I chose the second names, May and Jane, for my grandmothers. Angus chose the third names, for two little Scottish islands: Kerrera and Tanera.

A week after the twins were born – long before we made the ambitious move to Camden – we ferried our precious, newborn, identical babies in the back of the car, through the freezing sleet, home to our humble apartment. And we were so pleased with the result of our name-making efforts, we laughed and kissed, exultantly, as we parked – and said the names over and over.

Kirstie Jane Kerrera Moorcroft.

Lydia May Tanera Moorcroft.

As far as we were concerned, we had names that were subtly intertwined, and apposite for twins; we had names that were poetic and pretty and nicely paired, without going anywhere near Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

So what happened then?

It is time to sort the loft.

Climbing the stepladder, I shove hard against the trapdoor – and with a painful creak it flies open, quite suddenly, slamming against the rafters with a smash. The sound is so loud, so obtrusive, it makes me hesitate, tingling with nerves: as if there is something up here, asleep – which I might have just woken.

Pulling the torch from the back pocket of my jeans, I switch it on. And direct it upwards.

The square of blackness stares down at me. A swallowing void. Again, I hesitate. I am trying to deny that frisson of fear. But it is there. I am alone in the house – apart from Beany, who is sleeping in his basket in the kitchen. I can hear the November rain pattering on the slates of the roof above me, up there in the blackness. Like many fingernails tapping in irritation.

Tap tap tap.

Anxieties stir in my mind. I climb another rung on the stepladder, thinking about Kirstie and Lydia.

Tap Tap Tap. Kirstie And Lydia.

When we brought the twins home from hospital, we realized that, yes, we might have sorted the names satisfactorily, but we still had another dilemma: differing between them in person was much harder.

Because our twins matched. Superbly. They were amongst the most identical of identicals, they were the kind of brilliant ‘idents’ that made nurses from other wards cross long corridors, just to ogle our amazing twins.

Some monozygotic twins are not that identical at all. They have different skin tones, different blemishes, very different voices. Others are mirror-image twins, they are identical but their identicality is that of a reflection in the mirror, left and right are switched: one twin will have hair that swirls clockwise, the other will have hair that swirls anti-clockwise.

But Kirstie and Lydia Moorcroft were true idents: they had identically snowy-blonde hair, exactly matching icy-blue eyes, precisely the same button-noses, the same sly and playful smiles, the same perfect pink mouths when they yawned, the same creases and giggles and freckles and moles. They were mirror images, without the reversal.

Tap, tap, tap …

Slowly and carefully, maybe a little timidly, I ascend the last rungs of the ladder and peer into the gloom of the attic, following the beam of my torch. Still thinking. Still remembering. My torch-beam picks out the brown metal frame of a Maclaren twin buggy. It cost us a fortune at the time, but we didn’t care. We wanted the twins to sit side by side, staring ahead, even as we wheeled them around. Because they were a team from birth. Babbling their twinspeak, entirely engrossed in each other: just as they had been from conception.

Through my pregnancy, as we went from one sonogram to the next, I actually watched the twins move closer, inside me – going from body contacts in week 12, to ‘complex embraces’ in week 14. By week 16, as my paediatrician pointed out, my twins were occasionally kissing.

The noise of the rain is more persistent now, like an irritated hiss. Hurry up. We’re waiting. Hurry up.

I do not need encouragement to hurry. I want to get this job done. Briskly I scan the darkness – and my torch-beam alights on an old, deflated Thomas the Tank Engine daybed. Thomas the Tank Engine leers at me, dementedly cheerful. Red and yellow and clownish. That can definitely stay. Along with the other daybed, which must be up here. The blue one we bought for Kirstie.

Daughter one. Daughter two. Yellow and blue.

At first, we differentiated our babies by painting one of their respective fingernails, or toenails, yellow or blue. Yellow was for Lydia, because it rhymed with her nickname: Lydee-lo. Yell-ow. Blue was for Kirstie. Kirstie-koo.

This nail-varnishing was a compromise. A nurse at the hospital advised us to have one of the twins tattooed in a discreet place: on a shoulder-blade, perhaps, or at the top of an ankle – just a little indelible mark, so there could be no mistake. But we resisted this notion, as it seemed far too drastic, even barbaric: tattooing one of our perfect, innocent, flawless new children? No.

Yet we couldn’t do nothing. So we relied on nail varnish, diligently and carefully applied once a week, for a year. After that – until we were able to distinguish them by their distinctive personalities, and by their own responses to their own names – we relied on the differing clothes we gave the girls; some of the same clothes that are now bagged in this dusty loft.

As with the nail varnish, we had yellow clothes for Lydie-lo. Blue clothes for Kirstie-koo. We didn’t dress them entirely in block colours; a yellow girl and a blue girl, but we made sure that Kirstie always had a blue jumper, or blue socks, or blue bobble hat, while the other was blue-less; meanwhile Lydia had a yellow T-shirt, or maybe a dark yellow ribbon in her pale yellow hair.

Hurry now. Hurry up.

I want to hurry, but it also seems wrong. How can I be businesslike up here? In this place? The cardboard boxes marked L for Lydia are everywhere. Accusing, silent, loaded. The boxes that contain her life.

I want to shout her name: Lydia. Lydia. Come back. Lydia May Tanera Moorcroft. I want to shout her name like I did when she died, when I stared down from the balcony, and saw her little body, splayed and yet crumpled, still breathing, but dying.

And now I am gagging on the attic dust. Or maybe it is the memories.

Little Lydia running into my arms as we tried to fly kites on Hampstead Heath and she got scared by the rippling noise; little Lydia sitting on my lap earnestly writing her name for the first time, in waxy scented crayon; little Lydia dwarfed in Daddy’s big chair, shyly hiding behind a propped atlas as large as herself. Lydia, the silent one, the bookish one, the soulful one, the slightly lost and incomplete one – Lydia the twin like me. Lydia who once said, when she was sitting with her sister on a bench in a park: Mummy, come and sit between me so you can read to us.

Come and sit between me? Even then, there was some confusion, a blurring of identity. Something slightly unnerving. And now beloved Lydia is gone. Isn’t she? Or maybe she is alive down there, even as her stuff is crated and boxed up here? If that is the case, how would we possibly untangle this, without destroying the family?

The complexities are intolerable. I am talking to myself.

Work, Sarah, work. Sort the loft. Do the job. Ignore the grief, get rid of the stuff you don’t need, then move to Scotland, to Skye, the open skies: where Kirstie – Kirstie, Kirstie, Kirstie – can run wild and free. Where we can all soar away, escaping the past, like the eiders flying over the Cuillins.

One of the boxes is ripped open.

I stare, bewildered, and shocked. Lydia’s biggest box of toys has been sliced open. Brutally. Who would do that? It has to be Angus. But why? And with such careless savagery? Why wouldn’t he tell me? We discussed everything to do with Lydia’s things. But now he has been retrieving Lydia’s toys, without telling me?

The rain is hissing, once again. And very close, a few feet above my head.

Leaning into the opened box, I pull back a flap to have a look, and as I do, I hear a different noise – a distinctive, metallic rattle. Someone is climbing the stepladder?

Yes.

The noise is unmistakable. Someone is in the house. How did they get in without my hearing? Who is this climbing into the loft? Why didn’t Beany start barking, in the kitchen?

I stand back. Absurdly frightened.

‘Hello? Hello? Who is it? Hello??’

‘All right, Gorgeous?’

‘Angus!’

He smiles in the half-light which shines from the landing beneath. He looks definitely odd: like a cheap horror movie villain, someone illuminated from below by a ghoulish torch.

‘Jesus, Angus, you scared me!’

‘Sorry, babe.’

‘I thought you were on the way to Scotland?’

Angus hauls himself up, and stands opposite. He is so tall – six foot three – he has to stoop slightly, or crack his dark handsome head on the rafters.

‘Forgot my passport. You have to take them these days – even for domestic flights.’ Angus is glancing beyond me, at the ripped-open carton of toys. Motes of dust hang in the air, between our two faces, caught by my torchlight. I want to shine the torch right in his eyes. Is he frowning? Smiling? Looming angrily? I cannot see. He is too tall, there is not enough light. But the mood is awkward. And strained.

He speaks. ‘What are you doing, Sarah?’

I turn my torch-beam, so it shines directly on the cardboard box. Crudely knifed open.

‘What it looks like?’

‘OK.’

His silhouette, with the downstairs light behind him, has an uncomfortable shape, as if he is tensed, or angry. Menacing. Why? I talk in a hurry.

‘I’m sorting all this stuff. Gus, you know we have to do something, don’t we? About – About—’ I swallow away the grief, and gaze into the shadows of his face. ‘We have to sort Lydia’s toys and clothes. I know you don’t want to, but we have to decide. Do they come with us, or do we do something else?’

‘Get rid?’

‘Yes … Maybe.’

‘OK. OK. Ah. I don’t know.’

Silence. And the ceaseless rain.

We are stuck here. Stuck in this place, this groove, this attic. I want us to move on, but I need to know the truth about the box.

‘Angus?’

‘Look, I’ve got to go.’ He is backing away, and heading for the ladder. ‘Let’s talk about it later, I can Skype you from Ornsay.’

‘Angus!’

‘Booked on the next flight, but I’ll miss that one too, if I’m not careful. Probably have to overnight in Inverness now.’ His voice is disappearing as he clambers down the ladder. He is leaving – and his exit has a furtive, guilty quality.

‘Wait!’

I almost trip over, in my haste to follow him. Slipping down the ladder. He is heading for the stairs.

‘Angus, wait.’

He turns, checking his wristwatch as he does.

‘Yeah?’

‘Did you—’ I don’t want to ask this; I have to ask this. ‘Gus. Did you open the box of Lydia’s toys?’

He pauses. Fatally.

‘Sure,’ he replies.

‘Why, Angus? Why on earth did you do that?’

‘Because Kirstie was bored with her toys.’

His face has an expression that is designed to appear relaxed. And I get the horrible sensation that he is lying. My husband is lying to me.

I’m lost; yet I have to say something.

‘So, Angus, you went into the loft and got one out? One of Lydia’s toys? Just like that?’

He stares at me, unblinking. From three yards down the landing, with its bare pictureless walls and the big dustless squares, where we have already shifted furniture. My second-favourite bookcase, Angus’s precious chest of drawers, a legacy from his grandmother.

‘Yes. So? Hm?? What’s the problem, Sarah? Did I cross into enemy territory?’ His reassuring face is gone. He is definitely frowning. It is that dark, foreboding frown, which presages anger. I think of the way he hit his boss. I think of his father who beat his mother: more than once. No. This is my husband. He would never lay a finger on me. But he is very obviously angry as he goes on: ‘Kirstie was bored and unhappy. Saying she missed Lydia. You were out, Sarah. Coffee with Imogen. Right? So I thought, why not get her some of Lydia’s toys. Mm? That will console her. And deal with her boredom. So that’s what I did. OK? Is that OK?’

His sarcasm is heavy. And bitter.

‘But—’

‘What would you have done? Said no? Told her to shut up and play with her own toys? Told her to forget that her sister existed?’

He turns and crosses the landing – and begins to descend the stairs. And now I’m the one that feels guilty. His explanation makes sense. Yes, that’s what I would do, in the same situation. I think.

‘Angus—’

‘Yes?’ He pauses, five steps away.

‘I’m sorry. Sorry for interrogating you. It was a bit of a shock, that’s all.’

‘Tsch.’ He looks upwards, and his smile returns. Or at least a trace of it. ‘Don’t worry about it, darling. I’ll see you in Ornsay, OK? You take the low road and I’ll take the high road.’

‘And you’ll be in Scotland before me?’

‘Aye!’

He is laughing now, in a mirthless way, and then he is saying goodbye, and then he is turning to leave: to get his passport and his bags, to go and fly up to Scotland.

I hear him in the kitchen. His white smile lingers in my mind.

The door slams, downstairs. Angus is gone. And quite suddenly: I miss him, physically.

I want him. Still. More. Maybe more than ever, as it has been too long.

I want to tempt him back inside, and unbutton his shirt, and I want us to have sex as if we haven’t had sex in many months. Even more, I want him to want to do that to me. I want him to march back into the house and I want him to strip away my clothes: just like we did, in the beginning, in our first years, when he would come home from work and – without a word passing between – we would start undressing in the hall and we would make love in the first place we found: on the kitchen table, on the bathroom floor, in the rainy garden, in a delirium of beautiful appetite.

Then we’d lie back and laugh at the sheen of happy sweat that we shared, at the blatant trail of clothes we’d left behind, like breadcrumbs in a fairy tale, leading from the front door to our lovemaking, and so we’d follow our clothes back, picking up knickers, then jeans, then my shirt, his shirt, then a jacket, my jumper. And then we’d eat cold pizza. Smiling. Guiltless. Jubilant.

We were happy, then. Happier than any other couple I’ve known. Sometimes I actively envy us, as we were. Like I am the jealous neighbour of my previous self. Those bloody Moorcrofts, with their perfect life, completed by the adorable twins, then the beautiful dog.

And yet, and yet – even as the jealousy surges, I know that this completion was something of an illusion. Because our life wasn’t always perfect. Not always. In those long dark months, immediately following the birth, we almost broke up.