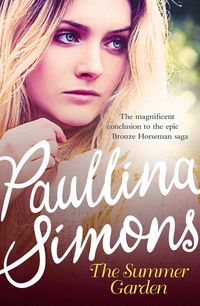

The Summer Garden

The next morning Tatiana went down to the docks. Jimmy’s sloop was there, and Jimmy was doing his best to repair some damage to the side. “Hey, little guy,” he said to Anthony. “Your dad back yet? I gotta go and get me some lobsters or I’m gonna go broke.”

“He’s not back yet,” said Anthony. “But he’s going to bring me a toy soldier.”

Tatiana wavered on her calf legs. “Jim, he didn’t say anything to you about how many days he was going to take off?”

Jimmy shook his head. “He did say if I wanted to, I could hire one of the other guys coming here looking for work. If he doesn’t come back soon, I’m gonna do it. I gotta get back out there.”

The morning was dazzling.

Tatiana, dragging Anthony by the hand, practically ran uphill to Bessie’s and knocked until Bessie woke up and came miserably to the door. Tatiana, without apologizing for the early call, asked if Bessie had heard from Nick or from the hospital.

“No,” Bessie said gruffly. Tatiana refused to leave until Bessie called the hospital, only to find out that the colonel had been admitted without incident two days ago. The man who brought him stayed for one day and then left. No one knew anything else about Alexander.

Another day passed.

Tatiana sat on the bench by the bay, by the morning water, and watched her son push himself on a tire swing. Her arms were twisted around her stomach. She was trying not to rock like Alexander rocked at three o’clock in the morning.

Has he left me? Did he kiss my hand and go?

No. It wasn’t possible. Something’s happened. He can’t cope, can’t make it, can’t find a way out, a way in. I know it. I feel it. We thought the hard part was over—but we were wrong. Living is the hardest part. Figuring out how to live your life when you’re all busted up inside and out—there is nothing harder. Oh dear God. Where is Alexander?

She had to go to Bangor immediately. But how? She didn’t have a car; would she and Ant go there by bus? Would they leave Stonington for good, leave their things? And go where? But she had to do something, she couldn’t just continue to sit here!

She was clenched inside, outside.

She had to be strong for her son.

She had to be resolute for him.

Everything was going to be all right.

Like a mantra. Over and over.

This is my vicious dream, Tatiana’s entire body shouted. I thought it was like a dream that he was with me again, and I was right, and now I’ve opened my eyes, and he’s gone like before.

Tatiana was watching Anthony swing, looking beyond him, dreaming of one man, imagining only one other heart in the vastness of the universe—then, now, as ever. She still flew to him.

Is he still alive?

Am I still alive?

She thought so. No one could hurt this much and be dead.

“Mama, are you watching me? I’m going to spin and spin and spin until I get dizzy and fall down. Whee! Are you watching? Watch, Mama!”

Her eyes were glazed over. “I’m watching, Antman. I’m watching.”

The air smelled so August, the sun shone so brightly, the pines, the elms, the cones, the sea, the spinning boy, just three, the young mother, not even twenty-three.

Tatiana had imagined her Alexander since she was a child, before she believed that someone like him was even possible. When she was a little girl, she dreamed of a fine world in which a good man walked its winding roads, perhaps somewhere in his wandering soul searching for her.

On the Banks of the Luga River, 1938

Tatiana’s world was perfect.

Life may not have been perfect; far from it. But in the summer, when the day began almost before the last day ended, when the crickets sang all night and cows mooed before dreams fled, when the smells of summer June in the village of Luga were sharp—the cherry and the lilacs and the nettles in the soul from dawn to dusk—when you could lie in the narrow bed by the window and read books about the Grand Adventure of Life and no one disturbed you—the air so still, the branches rustling and, not far, the Luga River rushing—then the world was a perfect place.

And this morning young Tatiana was skipping down the road, carrying two pails of milk from Berta’s cow. She was humming, the milk was spilling, she was hurrying so she could bring the milk back and climb into bed and read her marvelous book, but she couldn’t help skipping, and the milk couldn’t help spilling. She stopped, lowered the rail over her shoulders onto the ground, picked up one pail and drank the warm milk from it, picked up the other and drank some more. Replacing the rail around her shoulders she started skipping again.

Tatiana was one elongated reedy limb from toe to fingers, all one straight line, feet, knees, thighs, hips, ribs, chest, shoulders, a stalk, tapering off in a slender neck and expanding into a round Russian face with a high forehead, a strong jaw, a pink smiling mouth and white teeth. Her eyes glinted green with mischief, her cheeks and small nose were drowned in freckles. The joyous face was framed with white blonde hair, just wispy feathers falling on her shoulders. No one could sit by Tatiana without caressing her silky head.

“TATIANA!” The scream from the porch.

Except maybe Dasha.

Dasha was always shouting. Tatiana, this, Tatiana, that. She is going to have to learn to relax and lower her voice, Tatiana thought. Though why should she? Everyone in Tatiana’s family hollered. How else could one possibly be heard? There were so many of them. Well, her gray quiet grandfather managed somehow. Tatiana managed—somehow. But everyone else, her mother, her father, her sister, even her brother, Pasha—what did he have to shout about?—shouted as if they were just coming into the world.

The children played noisily and the grown-ups fished and grew vegetables in their yards. Some had cows, some had goats; they bartered cucumbers for milk and milk for grain; they milled their own rye and made their own pumpernickel bread. The chickens laid eggs and the eggs were bartered for tea with people from the cities, and once in a while someone brought sugar and caviar from Leningrad. Chocolate was as rare and expensive as diamonds, which was why when Tatiana’s father—who had left for a business trip to Poland recently— asked his children what they wanted for gifts, Dasha instantly said chocolate. Tatiana wanted to say chocolate, too, but instead said, maybe a nice dress, Papa? All her dresses were hand-me-downs from Dasha and much too big.

“TATIANA!” Dasha’s voice was now coming from the yard.

Turning her reluctant head, Tatiana leveled her bemused gaze at her sister, standing at the gate with her exasperated arms at her large hips. “Yes, Dasha?” she said softly. “What is it?”

“I’ve been calling you for ten minutes! I’m hoarse from shouting! Did you hear me?” Dasha was taller than Tatiana, and full-figured; her unruly curly brown hair was tied up in a ponytail, her brown eyes indignant.

“No, I didn’t hear,” Tatiana said. “Next time, maybe shout louder.”

“Where have you been? You’ve been gone two hours—to get milk from five houses up the road!”

“Where’s the fire?”

“Stop it with your fresh lip this instant! I’ve been waiting for you.”

“Dasha,” said Tatiana philosophically, “Blanca Davidovna says that Christ says that blessed are the patient.”

“Oh, you’re a fine one to talk, you’re the most impatient person I know.”

“Well, tell that to Berta’s cow. I was waiting for it to come back from pasture.”

Dasha took the pails off Tatiana’s shoulders. “Berta and Blanca fed you, didn’t they?”

Tatiana rolled her eyes. “They fed me, they kissed me, they sermonized me. And it’s not even Sunday. I’m fed and cleansed and one with the Lord.” She sighed. “Next time you can go get your own milk, you impatient heathen.”

Tatiana was three weeks from fourteen, while Dasha had turned twenty-one in April. Dasha thought she was Tatiana’s second mother. Their grandmother thought she was Tatiana’s third mother. The old ladies who gave Tatiana milk and talked to her about Jesus thought they were her fourth, fifth and sixth mothers. Tatiana felt that she barely needed the one loud exasperated mother she had—thankfully in Leningrad at the moment. But Tatiana knew that for one reason or another, through no fault of her own, women, sisters, other people felt a need to mother her, smother her more like it, squeeze her in their big arms, braid her wispy hair, kiss her freckles, and pray to their God for her.

“Mama left me in charge of you and Pasha,” Dasha declared autocratically. “And if you’re going to give me your attitude, I won’t tell you the news.”

“What news?” Tatiana jumped up and down. She loved news.

“Not telling.”

Tatiana skipped after Dasha up the porch and into their house. Dasha put the pails down. Tatiana was wearing a little-girl sundress and bouncing up and down. Without warning she flung herself onto her sister, who was nearly knocked to the floor before she caught her footing.

“You shouldn’t do that!” Dasha said but not angry. “You’re getting too big.”

“I’m not too big.”

“Mama is going to kill me,” said Dasha, patting Tatiana’s behind. “All you do is sleep and read and disobey. You don’t eat, you’re not growing. Look how tiny you are.”

“I thought you just said I was too big.” Tatiana’s arms were around Dasha’s neck.

“Where’s your crazy brother?”

“He went fishing at dawn,” Tatiana said. “Wanted me to come too. Me get up at dawn. I told him what I thought of that.”

Dasha squeezed her. “Tania, I have kindling that’s fatter than you. Come and eat an egg.”

“I’ll eat an egg if you tell me your news,” said Tatiana, kissing her sister’s cheek, then the other cheek. Kiss kiss kiss. “You should never keep good news all to yourself, Dasha. That’s the rule: Bad news only to yourself but good news to everybody.”

Dasha set her down. “I don’t know if it’s good news but … We have new neighbors,” she said. “The Kantorovs have moved in next door.”

Tatiana widened her eyes. “You don’t say,” she said in a shocked voice, grabbing her face. “Not the Kantorovs!”

“That’s it, I’m not speaking to you anymore.”

Tatiana laughed. “You say the Kantorovs as if they are the Romanovs.”

In a thrilled tone, Dasha continued. “It’s rumored they’re from Central Asia! Turkmenistan, maybe? Isn’t that exciting? Apparently they have a girl—a girl for you to play with.”

“That’s your news?” said Tatiana. “A Turkmeni girl for me to play with? Dasha, you’ve got to do better than that. I have a village-full of girls and boys to play with—who speak Russian. And cousin Marina is coming in two weeks.”

“They also have a son.”

“So?” Tatiana looked Dasha over. “Oh. I see. Not my age. Your age.”

Dasha smiled. “Yes, unlike you, some of us are interested in boys.”

“So really, it’s not my news. It’s your news.”

“No. The girl is for you.”

Tatiana went with Dasha on the porch to eat a hard-boiled egg. She had to admit she was excited, too. New people didn’t come to the village very often. Never actually. The village was small, the houses were let out for years to the same people, who grew up, had children, grew old.

“Did you say they moved in next door?”

“Yes.”

“Where the Pavlovs lived?”

“Not anymore.”

“What happened to them?”

“I don’t know. They’re not there.”

“Well, obviously. But what happened to them? Last summer they were here.”

“Fifteen summers they were here.”

“Fifteen summers,” Tatiana corrected herself, “and now new people have moved into their house? Next time you’re in town, stop by the local Soviet council and ask the Commissar what happened to the Pavlovs.”

“Are you out of your mind, such as it is? I’m going to the Soviet to ask where the Pavlovs went? Just eat, will you? Have the egg. Stop asking so many questions. I’m tired of you already and it’s only morning.”

Tatiana was sitting, cheeks like a chipmunk, the whole egg uneaten in her mouth, her eyes twinkling. Dasha laughed, pulling Tatiana to herself. Tatiana moved away. “Stay still,” said Dasha. “I have to rebraid your hair, it’s a mess. What are you reading now, Tanechka?” she asked as she started unbraiding it. “Anything good?”

“Queen Margot. It’s the best book.”

“Never read it. What’s it about?”

“Love,” said Tatiana. “Oh, Dasha—you’ve never dreamed of such love! A doomed soldier La Môle falls in love with Henry IV’s unhappy Catholic wife, Queen Margot. Their impossible love will break your heart.”

Dasha laughed. “Tania, you are the funniest girl I know. You know absolutely nothing about anything, yet talk in thrall of words of love on a page.”

“Obviously you’ve never read Queen Margot,” Tatiana said calmly. “It’s not words of love.” She smiled. “It’s a song of love.”

“I don’t have the luxury of reading about love. All I do is take care of you.”

“You leave a little time for some nighttime social interaction.”

Dasha pinched her. “Everything is a joke to you. Well, just you wait, missy. Someday you won’t think that social interaction is so funny.”

“Maybe, but I’ll still think you’re so funny.”

“I’ll show you funny.” Dasha knocked her back on the couch. “You urchin,” she said. “When are you going to grow up? Come, I can’t wait for your impossible brother anymore. Let’s go meet your new best friend, Mademoiselle Kantorova.”

Saika Kantorova.

The summer of 1938, when she turned fourteen, was the summer that Tatiana grew up.

The people who moved in next door were nomads, drifters from parts of the world far removed from Luga. They had odd Central Asian names. The father, Murak Kantorov, too young to be retired, mumbled that he was a retired army man. But his black hair was long and tied in a ponytail. Did soldiers have long hair like that? The mother, Shavtala, said she was a non-retired teacher “of sorts.” The nineteen-year-old son, Stefan, and the fifteen-year-old daughter, Saika, said nothing except to pronounce Saika’s name. “Sah-EE-ka.”

Was it true that they came from Turkmenistan? Sometimes. Georgia? Occasionally. The Kantorovs answered all questions with vagueness.

Usually new people were friendlier, not as watchful or silent. Dasha tried. “I’m a dental assistant. I’m twenty-one. What about you, Stefan?”

Dasha was already flirting! Tatiana coughed loudly. Dasha pinched her. Tatiana wanted to make a joke, but there didn’t seem to be any room for jokes in the crowded dark room where too many people stood awkwardly. The sun was blazing outside, yet inside, the unwashed curtains were drawn over the filthy windows. The Kantorovs had not unpacked their suitcases. The house had been left furnished by the Pavlovs, who seemed not so much to have left as to have stepped out.

There were some new things on the mantel. Photos, pictures, strange sculptures and small gilded paintings, like icons, though not of Jesus or Mary … but of things with wings.

“Did you know the Pavlovs?” asked Tatiana.

“Who?” the father said gruffly.

“The Pavlovs. This was their house.”

“Well, it’s not their house anymore, is it?” said the raven mother.

“They won’t be back,” said Murak. “We have papers from the Soviet. We are registered to stay here. Why so many questions from a child? Who wants to know?” He pretended to smile.

Tatiana pretended to smile back.

When they were outside, Dasha hissed, “Stop it! I can’t believe you’re already starting with your inane questions. Keep quiet, or I swear I’ll tell Mama when she comes.”

Dasha, Stefan, Tatiana and Saika stood in the sunlight.

Tatiana said nothing. She wasn’t allowed to ask questions.

Finally Stefan smiled at Dasha.

Saika watched Tatiana guardedly.

It was at that moment that Pasha, little and fast, ran up the steps of the house, shoved a bucket with three striped bass into Tatiana’s body and said loudly, “Ha, little smart Miss Know-it-nothing, look what I caught today—”

“Pasha, meet our new neighbors,” interrupted Dasha. “Pasha—this is Stefan, and Saika. Saika is your age.”

Now Saika smiled. “Hello, Pasha,” she said.

Pasha smiled broadly back. “Well, hello, Saika.”

“And how old are you?” Saika said, appraising him.

“Well, I’m the same age as this one over here.” Dark-haired Pasha pulled hard on Tatiana’s blonde braid. She shoved him. “We’re fourteen soon.”

“You’re twins!” exclaimed Saika, looking at them intently. “What do you know. Obviously not identical.” She smirked. “Well, well. You seem so much older than your sister.”

“Oh, he is so much older than me,” said Tatiana. “Nine minutes older.”

“You seem older than that, Pasha.”

“How much older do I seem, Saika?” Pasha grinned. She grinned back.

“Like twelve minutes older,” Tatiana grumbled, stifling the desire to roll her eyes, and “accidentally” tripping over the bucket, spilling his precious fish onto the grass. Pasha’s attention was loudly and properly diverted.

To wake up and be still with the morning, to wake up and feel the sun, to not do, to not think, to not fret. Tatiana lived in Luga unbothered by the weather, for when it rained she read, and when it was sunny she swam. She lived in Luga unbothered by life: she never thought about what she wore, for she had nothing, or what she ate, because it was always adequate. She lived in Luga in timeless childhood bliss without a past and without a future. She thought there was nothing in the world that a summer in Luga could not cure.

The Last Snow, 1946

“Mama, Mama!”

Shuddering she came to and swirled around. Anthony was running, pointing to the sloping hill, down which walked Alexander. He was wearing the clothes he left in.

Tatiana got up. She wanted to run to him, too, but her legs wouldn’t carry her. They couldn’t even support her standing. Anthony, the brave boy, jumped straight into his father’s arms.

Carrying his son, Alexander walked to Tatiana on the pebbled beach and set him down.

“Hey, babe,” he said.

“Hey,” she said, barely able to keep her composed face.

Unshaven and unclean, Alexander stood and stared at her with gaunt black rings under his eyes, with a barely composed face of his own. Tatiana forgot about herself and went to him. He bent deeply to her, his face pressed into her neck, into the braids of her hair. Her feet remained on the ground and her arms were around him. Tatiana felt such black despair coming from Alexander that she started to convulse.

Gripping her tighter, his arms surrounding her, he whispered, “Shh, shh, come on, the boy …” When he released her, Tatiana didn’t look up, not wanting him to see the fear for him in her eyes. There was no relief. But he was with her.

Tugging on his father’s arm, Anthony asked, “Dad, why did you take so long to come back? Mama was so worried.”

“Was she? I’m sorry Mommy was worried,” Alexander said, not looking at her. “But, Ant, toy soldiers aren’t easy to come by.” He took out three from his bag. Anthony squealed.

“Did you bring Mama anything?”

“I didn’t want anything,” said Tatiana.

“Did you want this?” He took out four heads of garlic.

She attempted a smile.

“What about this?” He took out two bars of good chocolate.

She attempted another smile.

As they were walking up the hill, Alexander, carrying Anthony, gave Tatiana his arm. Putting her arm through his, she pressed herself against him for a moment before walking on.

Alexander was cleaned, bathed, shaved, fed. Now in their little narrow bed she was lying on top of him, kissing him, cupping him, caressing him, carrying on, crying over him. He lay motionless, soundless, his eyes closed. The more clutching and desperate her caresses became, the more like a stone he became, until finally, he pushed her off himself. “Come on now,” he said. “Stop it. You’ll wake the boy.”

“Darling, darling …” she was whispering, reaching for him.

“Stop it, I said.” He took her hands off him.

“Take off your vest, darling,” Tatiana whispered, crying. “Look, I’ll take off my nightgown, I’ll be naked, like you like …”

He stopped her. “No, I’m exhausted. You’ll wake the boy. The bed creaks too much. You’re making too much noise. Stop crying, I said; stop carrying on.”

She didn’t know what to do. Caressing him until he was swollen in her hands, she asked if he wanted something from her. He shrugged.

Trembling, she put him in her mouth but couldn’t continue; she was choking, she was so sad. Alexander sighed.

Getting off the bed, he brought her down to the plank wood floor, turned her on her hands and knees, told her to keep quiet, and took her from behind, holding her at the small of her back with one hand and at her hip with the other to keep her steady. When he was done, he got up, got back into bed, and never made a sound.

After that night, Tatiana lost her ability to talk to him. That he wouldn’t just tell her what was going on with him was one thing. But the fact that she couldn’t find the courage to ask was wholly another. The silence between them grew in black chasms.

For three subsequent evenings, Alexander wouldn’t stop cleaning his weapons. That he had the weapons was troubling enough, but he wouldn’t part with any of the ones he brought back from Germany, not the remarkable Colt M1911 .45 caliber pistol she had bought for him, not the Colt Commando, not even the 9mm P-38. The M1911, the king of pistols, was Alexander’s favorite—Tatiana could tell by how long he cleaned it. She would go to put Anthony to bed, and when she returned outside, he would still be sitting in the chair, sliding the magazine in and out, cocking it, putting the safety on it and back again, wiping all the parts with cloth.

For three subsequent evenings Alexander wouldn’t touch her. Tatiana, not knowing, not understanding, but desperately wanting to make him happy, stayed away, hoping that eventually he would explain, or evolve back into what they had. He evolved so slowly. On the fourth night Alexander pulled off all his clothes and stood in front of her naked in the dark, as she sat on the bed, about to get in. She looked up at him. He looked down at her. You want me to touch you? she whispered uncertainly, her hands rising to him. Yes, he said. I want you to touch me, Tatiana.

He evolved a little but never explained anything in the dark, in their little room with Anthony sleeping.

The days became cooler, the mosquitoes left. The leaves started changing. Tatiana didn’t think there was breath left in her body to sit on the bench and watch the hills of cinnabar and wine and gold reflect off the still water.

“Anthony,” she whispered. “Is this so beautiful or what?”

“It’s or what, Mama.” He was wearing his father’s officer’s cap, the one Dr. Matthew Sayers had given her years ago off a supposedly dead Alexander’s head. He has drowned, Tatiana, he is dead in the ice, but I have his cap; would you like it?

The beige cap with a red star, too big for Anthony, made Tatiana think of herself and her life in the past tense instead of in the present. Sharply regretting having given it to the boy, she tried to take it from him, to hide it from him, to put it away, but every morning Anthony said, “Mama, where is my cap?”

“It’s not your cap.”

“It is so. Dad told me it was mine now.”

“Why did you tell him he could have it?” she grumbled to Alexander one evening as they were ambling down to town.

Before he had a chance to reply, a young man, less than twenty, ran by, lightly touching Tatiana on her shoulder, and said with a wide, happy smile, “Hi there, girly-girl!” Saluting Alexander, he continued downhill.