Sea Room

For all the illusion of remoteness, the Shiants have never been parochial. They are part of the whole world and are a profoundly human landscape, the subject of stories, songs and poems. They have been the scene of attempted murder, witchcraft and terrible accidents. They have witnessed all kinds of happiness and cruelty. They have known great riches and devastating poverty. They can be as sweet as Eden and as malevolent as Hell. They can envelop you and reject you, seduce you into thinking nowhere on earth is as perfect and then make you long to be anywhere but this. I have never known a place where life is so thick, experience so immediate or the barriers between self and the world so tissue-thin. I love the Shiants for all their ragged, harsh and delicate glory and this book is a love letter to them.

2

EARLY APRIL AND A COLD WIND was cutting up from the south-west. Freyja was anchored in the little rocky inlet at the head of Flodabay on the east coast of Harris. A seal watched from the dark water. Acid streams were draining off the moorland into the sea. The boat swung a little and the reflected sun glinted up at the strakes of her bilges. I was shivering, not because of the cold, but because I was frightened at the idea of sailing out alone in this small boat to the Shiants. The halyard was slapping against the mast and the tiny waves clucked as they were caught against the underside of the hull. The shores of Flodabay were sallow and tussocky with the dead winter grasses and the boat was washed in late-winter sun. Freyja is sixteen feet from stem to stern and looks from the shore as slight as a balsawood toy. She and the Minch are not to the same scale.

It was the first time I was going to sail to the Shiants on my own. Always before, I had allowed myself to be carried out by fishermen from Scalpay or boatmen from Lewis, travelling as I now see it like a man in a sedan chair, gracefully picked up, carefully taken over and gently set down. That could never be enough. That was not being engaged with the place. An island can only be known and understood if the sea around it is known and understood.

Six months previously, I had read a history of the birlinn, the sailing galley descended from Viking boats that was used in these waters by the highland chiefs, at least until the seventeenth century. They raided and traded with them. Their lives were as much bound up with them as with any land-based habitation. The book described the carving of a birlinn surviving on the tomb of Alasdair Crotach, Hunchback Alasdair, the Macleod chieftain in Harris in the mid-sixteenth century. He was a violent man, the mass murderer of a cave-full of Macdonalds on Eigg, men, women and children, three hundred and ninety-five of whom he suffocated with the smoke of a fire lit at its narrow mouth.

This killer’s birlinn is an image of extraordinary beauty.

The form and curve of each strake, the fixings of the rudder, even the lay of the rope in the rigging: everything is carved with exactness, clarity and what can only be called love. Around it are the relative crudities of angels, apostles and biblical stories. Their forms never escaped the stone but the carved ship shows the panels of cloth in the bellied-out sail. It even shows the way a sail can be creased against a forestay that is faintly visible through it. Above all, though, it lovingly described the form of the hull, the depth of its keel and the fullness of the bilges. All of this was carved in millimetre detail, testament of something that mattered. The birlinn was shown at full stretch and fully rigged, but out of the water, so that the swept beauty of the hull could be seen. Only a shipwright or a sailor could have carved such a thing: it is the mental, not the actual image of a ship at sea, a depiction of what you can imagine of a boat at its most perfect moment, made by a man who knew it. The author of the birlinn history had set a Gaelic proverb at the head of his central chapter:

‘S beag ‘tha fios aig fear a bhaile,Cia’mar ‘tha fear na mara beò.

The landlubber [literally the man of the village] has no idea

How the sailor [the man of the sea] exists.

That was the gap I wanted to cross; to acquire the habits of mind which the carver of the birlinn had so easily conveyed. I rang the author, John MacAulay. He lived in Flodabay in South Harris. Did he know of anyone who might be able to build me a boat that would take on something of that Norse tradition? That I could sail single-handed? Which would be safe and strong enough to survive in the Minch, even on a bad day, and which might be hauled up a beach, at least with the help of a winch?

‘Ah yes,’ John said, a light, slight voice. Definite, polite, courteous, withdrawn, sharp, sprung.

‘In Harris, would that be?’ I asked him.

‘Yes, I think it would.’

Wonderful news. And who was the shipwright?

‘Well, I think you are speaking to him now.’

John MacAulay was not only a historian of the Viking inheritance, but a boat builder of thirty-five years’ experience. He had made and repaired fishing boats in the Shetland island of Unst, and at Oban and Kyle. He had been a fisherman and was an experienced yacht sailor. He was one of the leading experts on both the history of the sea kayak and the traditional working boats of the Hebrides. He was an elder of his church in Leverburgh and author of a book on the church at Rodel in which the birlinn carving was to be found. For two months or so John and I corresponded by letter and occasionally by phone. I said I thought I could do what I needed to do with a twelve-foot boat. He said it would have to be at least sixteen foot. ‘I’m not sending you out there in something twelve foot long.’ I wanted something ‘double-ended’, coming to a point at bow and stern. John said, ‘That would be a waste of wood. You’ll want a transom on it.’ A sixteen-footer with a transom – the stern cut off square – was the equivalent of a twenty-footer that came to a point at the stern. Timber in the treeless Hebrides was always at a premium. ‘It would be a waste of wood. And time. And money,’ he said.

He posted me drawings of the boat he proposed. Unpractised at reading such things, and unable to guess performance or quality from buttock lines or the sheer of the gunwale, I took him at his word. I had yet to meet him but even at a distance he exuded an authority and conviction which it was not easy to deny. I would turn repeatedly to a passage in his book about the birlinn:

A close relationship, like a spiritual bonding, develops between the shipwright and the finished vessel, which continues throughout its entire material life. It has been known for certain boatbuilders to refuse to build for a particular client, if they did not feel an affinity towards one another. A reputable shipwright might not want to see some work of devotion fall into the wrong hands, and would rather find some obscure reason for refusing to build, than later be in the position of accusing an untrustworthy client of incompetence …

Austerity lay like an acid on the page. The Nicolsons might claim to be descended from the ancient chiefs of Lewis. Their birlinn might have been run down by the Macleods in the Minch, somewhere off the Shiants. Norse blood might have been running in me, but it was scarcely the purest of streams. John MacAulay, though, was the real thing. ‘MacAulay,’ he said to me one day, ‘is only the Gaelic for Olafson.’ The world of the sagas, a thousand years away, came reeking down the telephone.

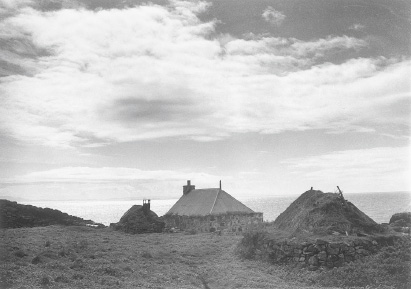

The severity was a guarantee of his seriousness. I met him for the first time when the boat was almost finished. His workshop is a Nissen hut on the shores of Flodabay. A curling strip of tarmac makes its tortuous way across rocks and around inlets down to the settlement. Nowhere in the British Isles that has been long inhabited can be bleaker than this. The ice-scraped gneiss shelters little more than dark peat hollows and sour grass. The houses of the people who live here are scattered along the road. There is no visible sign of community. It looks like a barren world.

That is certainly how outsiders have always seen such places: as an environment and a people in need of improvement and enrichment, a place of material poverty and actual sterility. But come a little closer and the picture turns on its head. A richness flowers among the rocks. John met me in front of the boat he had made. He stood four square, legs apart and shoulders back, resting a hand on the gunwale. His long, grey hair was brushed back from his temples. He wore a small grey moustache and looked me straight in the eye: a straight, calm, evaluating look. ‘Are you up to the boat I have made?’ it said. Could the shipwright trust the client? But instead, he said, ‘Welcome, welcome.’

We went over it together for two hours, inch by inch. Although I had paid for it, and I was to use it, I was to trust my life to it, there was no doubt whose boat this was. John was describing his world. The boat to my eye was extraordinarily deep and wide for its length: sixteen feet long but six feet, two inches in the beam, and drawing at least two feet below the water line at the stern. ‘Take me through it,’ I said. Little spits of rain were coming in through the open doors of the workshop. ‘This boat is for the Minch,’ he said. ‘She is not off the shelf. She knows the conditions in which she’ll have to work. And she’s within your capabilities for handling. Twelve feet would be too small and anything bigger would be too big for you.’

John enlarged on the difference between this and ‘most boats’. ‘Most boats are a tub’ – he outlined the body of a pig in the air – ‘and a keel. A tub for buoyancy, a keel for lateral stability. Easy to make, cheap to build. This boat is different. It’s the hull planking itself which makes the keel. It is a highly complex and integrated form, and that integral keel running the whole length of the boat gives you directional stability as well as lateral stability.’ The form he was describing clearly derived from the deep-draughted birlinn. There was ‘more boat in the water’ built like this. You might see her afloat and think, just from the shore, that she was a slip of a thing. She wouldn’t show a great deal. The meat of the boat was unseen, in the water, and it was that which made her a good sea boat and a good sailing boat. She had a better grip in the water that way and you wouldn’t get anything like the rolling effect you would with ‘most boats’.

Everything was precision here. The language John was using was scientific in its exactness. The saws, drawknives, hand-drills, chisels, disc-grinders and hammers were hung cleanly and neatly, ranged by size, along the corrugated metal walls of the workshop. A mallet and a measuring tape lay on the work bench. Timber was stacked on shelving in the roof and one of John’s padded checked shirts hung from the end of the baulks. The wind coming in from the large open garage doors was the only thing unregulated here. ‘Where did you learn to be so neat, John?’ I asked him.

‘I can’t bear untidiness of any kind,’ he said.

I felt a little fat in his presence, mentally fat, from the world beyond here, the world of cheap options and short cuts, the world of ‘most boats’, where the rigour of this man and his workshop was not applied. I slowly came to understand something: this was not a very large dinghy. It was a very small ship. This was the birlinn translated for me. All the principles of sea-kindliness, of robustness of construction and yet lightness of form, of a craft designed to protect its crew and save their lives, miraculously transmitted to this man and his meticulous workshop, had been poured into the boat which he would allow me to call mine. John himself, and the boat he had made, were a transmission from the world of the Shiants’ past.

But there was more to it. ‘The entry is fine’ – it comes to a sharp and narrow point at the bow – ‘which makes her easy to row. And the underwater lines are clean: a clean fine exit.’ Underwater, the stern sweeps to as narrow and subtle a point as the bow. Seen from astern, the boat’s form is a wineglass. I – the crew – would inhabit the bowl, but the sea would come into contact only with the stem of the glass. As far as the sea knew, the boat gradually slipped away to nothing. Smooth, laminar flow along the hull would allow her to slide along, no eddies, no drag. Only ‘amidships’ – John’s word, all the implications of this tradition buried in it – does she fill out. But again the middle path must be chosen. She is not so fine that she will roll too quickly, but not so full that the drag is too great. The mast and yardarm, cut and planed from lengths of Scottish larch, the oars (larch) and rudder (oak, bound and tipped with galvanised iron) had all been made by John without compromise or trimming. Everything was as full and robust as it needed to be, but not more than that. This was no butcher of a thing. It had a slightness for all its strength. He had forged the iron for the mooring rings, the eyebolts and hooks for the halyard, the upright pins for the rowlocks and the gudgeons and pintles for the rudder. Everything was fully itself, designed not only for appearance but to last and to work in difficult and harsh conditions. Nothing was too heavy or too massive. Accommodation was all.

‘A boat for the Shiants then?’ I said. John nodded silently. ‘I think she’s beautiful,’ I said. He said nothing, but shrugged.

‘How long will she last?’ I asked him.

‘It’ll last longer than you,’ he said, and then turning away, ‘There are boats at Geocrab, the next bay up, that are more than a hundred years old and they’re still sailing.’

‘And do you think I’ll make a good sailor of her?’

‘If you had another life,’ John said.

‘Ah yes,’ I said, reeling a little, ‘I suppose one needs to know these things instinctively.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘You need to be entirely conscious of what you are doing and why you are doing it.’

Sharp, educative, exact: the mind was as clear and as precisely arranged as the tools on the workshop wall. John uses words like ‘declivity’, ‘counteraction’, ‘silicon bronze’ as if they were chisels. One of his saws was stamped with its date of manufacture: 1948. It hung on its hook in as clean a condition as the day it was made.

It was not hostility. Far from it. He had done his extraordinary best for me. He had wetted the keel, as one should, with a glass of whisky when it was first laid. He had buried deep in the woodwork at the stern a threepenny bit from the year of his birth, 1941. He had given the stern his own signature, a little ‘tumblehome’, a slight curving of the hull in towards the gunwale ‘because it looked right.’ He had poured himself into this beautiful thing for me. But this is not a sentimental tradition. This was a man who had grown up with boats. He had been sailing his first small boat like this when he was a teenager. His grandfather and great-grandfather had big herring drifters, fifty, sixty, seventy feet long, built in Stornoway, with which they had followed the herring on its seasonal migration around Cape Wrath, through the Pentland Firth, down the east coast of Scotland and on as far as Yarmouth. The herring have long since gone now and that is not an option.

‘Is there much fishing in this loch now?’ a Lewis crofter was asked by one of the investigating Commissioners in 1894.

‘There used to be when herring came into it,’ he said. ‘There is very little fishing except when there are herring.’

‘Do you know the reason why the herring are not coming now?’

‘Providence,’ the crofter said, ‘the administration of the Creator.’

The herring are gone but John had been at sea all his life and he had completed a five-year apprenticeship in shipbuilding. Who was I to ask if I might be a sailor like them?

Looking back on it now, I can see that I was asking him for too much, too quickly. Again and again I asked him, ‘Show me how to do this, tell me about the tides, tell me how to cope when the wind and tide run into each other. Where are the places not to be? Take me out in the boat and show me how to do it.’ And again and again, with the mixture of sharpness and distance, he said no.

I was up for a week early in the year with a friend of mine, a writer, Charlie Boxer. Each of us was as green as the other, each as hurried and muddled in our dealing with the rig or our attempts to tack. He left us to it. Day after day, Charlie and I hacked along the Harris shore, seeing how close we could bring her to the wind, frightening ourselves in the tide rip off Stocanish, suddenly finding the boat going backwards in the tide while sailing at full speed with the wind, and once, like tourists, landing in the little loch at Scadabay to buy some tweed.

John came out with us once, a gentle afternoon in Flodabay, and the boat flew under his hands. Niftily, he threaded her through a maze of unseen rocks out to the headland on which a Norse seamark stood and then back to the jetty. He stood at the stern with the tiller between his knees, the nonchalant man against the sky behind him. He showed me, in other words, the condition I hoped to reach. It was not his business to provide any waymarks towards it.

And for all this I am grateful. I loved the boat. I felt that in the boat, and in this teaching by not teaching, I was learning more about the world of the islands than I had ever grasped. Here with John MacAulay I was seeing beyond their holiday face. The tradition in which he believed was too valuable to be tarted about.

When on that April morning, I finally left Flodabay in the boat, John helped me load her up with all my odds and ends in waterproof bags. It was, or so I felt anyway, an emotional moment. The tide that would carry me north would only start to run in the early afternoon and so most of the morning I was getting things ready. A seal dawdled in the weedy shadows. The oystercatchers peeped from one rock to the next. I had the mast up and the sail unfurled. Already there was some wear on the boat where Charlie and I had sailed her up and down the coast of Harris, the sheer presence of a friend in the boat giving me the confidence to do things I wouldn’t have dreamed of doing on my own. The cleats were now worn where the sheets had tightened against them. The knots in the oak thwarts had opened in a spell of dryish weather. I said goodbye to John, a hard handshake. He was off to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Clause 28, and all the larger questions of homosexuality which clustered around it, was the issue of the day. ‘Oh, you would be surprised. Even in the Church of Scotland there’s a big gay lobby,’ he said. He wasn’t in favour himself. I didn’t tell him that most of my family was gay, but I’m sure he guessed it anyway. I thanked him for everything he had done.

The inflatable dinghy in and deflated, the oars stowed, the charts in the stern sheets, the laminated folder of the pilot tucked in under the stern thwart, the compass, the VHF and GPS, the mobile phone and binoculars, the bread rolls I had bought outside Tarbert, the lump of cheese; my drysuit, life-jacket, harness, lifeline, the little knowledge I had acquired with Charlie of how the Minch might be, how it threatens you even on the gentlest of days: with all of this, and the trust in the boat, I was equipped. I raised the anchor, washed off the black mud that clung to it, stowed it away and hoisted the sail.

The wind, coming down off the hills in South Harris, snatching at the foot of the sail, pulled the bow around. The still bay water rippled against the strakes of the hull. The sunshine flicked up at me from each small wave. As the boat moved out towards the open sea, past Bogha Creag na Leum, the underwater rock which guards Flodabay against the unwary incomer, and as the surface of the water started to lift with the swelling of the Minch outside, there on the headland by the Norse seamark, a tall, lichened stone pillar, stood a man. He was waving to me. I couldn’t see for a moment who it was. I waved back, and then I realised: it was John MacAulay. He must have run half a mile to get there in time. He had made no mention of it, but this was his farewell, the shipwright saying goodbye to his boat. As the sea began to take up its longer, bigger rhythm, and the stem bit and rose in the swells, with the bow wave running and rippling the length of the hull beside me, and the wake starting to gurgle behind, I waved back to him.

‘Good luck!’ he shouted.

‘Thank you!’ I shouted back, ‘Thank you, thank you!’

The air has closed in and the north is now a featureless absence. Between me and the mist-wall, a gannet cruises above the Minch. It must be in from St Kilda, sixty miles away to the west, low over the water, quartering it, looking for the flash of silver there, cutting sickle curves across the grain of the swell. It is a frightening sea. I see a big tanker coming south down the Minch. The spray bursts around its bow as it slaps into each of the swells. No contact with its crew or master, but I feel them looking at me from the bridge and wondering what that tiny boat must be about. Not that the swells are particularly big; they lift Freyja five or six feet in a long, rolling motion. It is just that the boat seems small, the sea wide and the land in all directions a long way off. Like a climber on his ledge, I have to suppress the awareness of all that room beneath me. Concentrate on the boat. Look to the sail. Check you are on course. Do not consider the hugeness of the sea.

The muscles across my chest have tightened and my whole body is tensed, waiting for some relief. I am not at home here. I don’t have the sailor’s ease. I look at each coming sea as a possible enemy. The sea surface is streaked white as if the fat in meat has been dragged downwind. Why did I think this would be a thing to do, to push myself out here on a slightly difficult day, with the wind rising and the passage untried? It was not wise, but I am committed now. It would be just as bad turning back as going on. The sea extends like a hostile crowd around me. I want to arrive. I want to be out of uncertainty. At least on the island, however much the sea might batter it, there is no fear of the ground beneath your feet breaking or of it somehow abandoning you. An island is loyal in the way that a boat can never be. A boat can go wrong, the gear can fail. The sheer solid stillness of the islands is not like that. An island is a presence, not a motion, and there is faithfulness in rocks.

I look for the Shiants but they have yet to appear. I am shut in the world of the boat and the compass. At sea, something sixteen feet long does not feel large.

I wanted to call her Maighdean nan Eileanan Mora, the Gaelic for ‘Shiant Girl’ until John MacAulay pointed out that saying that to the Coastguard over the VHF was not going to sound quite right. Besides, the name wouldn’t fit on the boat. So I have called her Freyja, after the Norse goddess of love and fertility, who could turn herself into a falcon and fly for a day and a night over the sea; who could shepherd the fish into the nets of fishermen; who could happily sleep with an entire family of elves, each one of which would present her with a link in an amber necklace after the night she had given them. One shape Freyja would never adopt was the chaste and abstinent virgin. She was always fully engaged with life, ripe in body and desire.

I love Freyja’s beautiful fatness around her middle. (I had said this to John. ‘Not fat,’ he said. ‘Full.’) She is uncompromisingly robust and strongly nailed for all the travails she will have to go through; nothing fey but nothing brutish. The Norse used to have both their houses and their graves made in the shape of boats, smoothly narrowing to the ends. It is the most accommodating form man has ever devised. I focus on that, on the coherence of what John has made compared with all the incipient anarchy of the sea.