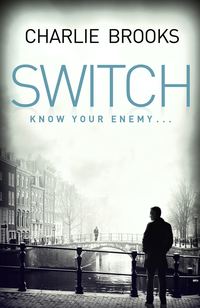

Switch

‘Is it the right age?’

‘Apparently. No idea who the artist is, but it’s 1600s. Don’t suppose he’d have been too happy if he’d known when he painted it that you were going to strip his paint off one day.’

Jacques shrugged his shoulders and turned it over to look at the back of the canvas. He seemed satisfied.

‘And the pigments?’

‘Exactly as you requested.’

Max met Gemma in the American Bar at the Hôtel de Paris. Gemma had arrived back first and taken the small table in the corner looking out on to Casino Square.

‘Shall we go to the casino this evening?’ Max asked as he drew up a chair. He was feeling elated. Revenge was going to be sweet.

‘And gamble?’

‘Well, you could. Maybe a little blackjack? Stick on twelve if the dealer has sixteen or less.’

‘You and your risk-assessing brain, Max. Always calculating the odds.’ In fact, she was working out what chance there was of running into Marchant with him.

‘Disappointing, this bar, don’t you think? Very plain. No imagination. No feel to it. How was your meeting? Productive?’

‘Yes. I think so. Drink?’

‘Bit early for me. I’ll have a cup of tea, please.’

Max caught the eye of a waiter who was busily doing nothing.

‘Monsieur, vous avez du Earl Grey? Et je voudrai également un grand whisky s’il vous plaît, Du Grouse, et une petite bouteille d’eau gazeuse.’

‘You’re quite sexy when you speak French,’ Gemma said from behind her newspaper.

‘I’d be even sexier if I could write it properly.’

This was a sore point for Max, Gemma knew, but she didn’t feel like hearing yet again how Pallesson had trashed him going to university. She put her hand on his thigh and rubbed it.

‘Tell me about your meeting.’

‘Well, anything I tell you would have to be erased from your mind. As for my mind, it’s currently contemplating something else,’ he whispered, reciprocating rather more daringly with his own hand.

‘Are you sure you had lunch with an old man? You seem to be—’

‘How was your massage?’ he interrupted.

‘Intimate. Very intimate. Anyway, I thought we were going to explore?’

But Max was having none of it.

‘We could go upstairs and explore,’ he said, downing his Scotch.

Gemma again made the mistake of walking out of the bathroom without tying her dressing gown. She may have got away with it that morning, but not now.

Max pushed aside her long hair and kissed the back of her neck. He felt a familiar response as her body shivered. Though he’d learnt most of his foreplay tips from the sex column in GQ magazine, over the years Gemma had taught him how to turn her on. Today, though, Max was in a rush. He was bursting.

As he pulled her closer to him, she could feel him rubbing against her La Perla-clad bottom.

Max had bought her the underwear a week before, after they’d shared a few glasses of champagne at the Harrods caviar bar. He’d tried not to show his shock when the shop assistant asked him for the best part of three hundred pounds in return for the small swatch of black lace. Now, as he pulled off her dressing gown, he could see it was money well spent.

‘Someone’s come back horny,’ Gemma whispered. ‘Who did you meet, again?’

His response was muffled as he carried on kissing and nibbling at her neck. His left hand reached round and unclipped her bra. She stopped asking questions and knelt on the bed in front of him.

Max just wanted to lose himself in an old-fashioned quickie.

‘My God. Something’s woken you up.’ Gemma was totally in his grip. Max was squeezing her bum as hard as he could. He was feeling uncontrollably selfish.

‘That wasn’t very gentlemanly,’ Gemma teased as Max collapsed on the bed next to her. ‘You don’t deserve it, but there’s a present for you under your pillow,’ she whispered into his ear. ‘Now that you’ve finished.’

He ran his hand underneath the crisp linen pillowcase and felt a small box. He flipped it open and found himself looking at the Vacheron Constantin watch. He was now wide awake.

‘Gemma! How did you know? This is …’

‘Do you like it?’

‘Like it?’ He kissed her on the nose. ‘I love it. But how …?’

‘Oh, a little bird told me. Rather a sexy little bird, actually. If you hadn’t flirted so much with her, she might not have remembered.’

‘You shouldn’t have. You spoil me.’

Gemma stroked Max’s arm and put her head on his shoulder, looking away from him.

‘I wish you had swept me up and given me security, Max,’ Gemma said, surprising Max with such sudden intensity.

Having been given such an expensive gift, Max felt guilty as his brain rapidly calculated what giving Gemma security would cost. And then wondered if Casper would find the watch on Gemma’s credit-card bill. Probably not. It would get lost amongst everything else.

‘You wish I were Casper?’

‘No, of course not. But you do understand why I married him, don’t you?’

‘Yes. Yes, I do,’ Max said as he looked at the watch.

‘You know I love Casper. In a way. We should probably have had children. That was my fault. I wasn’t sure at the time and it’s probably too late now. In more ways than one. But I can’t bear the thought of having nothing again, Max. Does that make me a bitch? Being here with you?’

‘No. Of course it doesn’t. If you don’t hurt Casper, how could it?’

Gemma didn’t really register his answer. Her mind was doing what it always did when the present was threatened by the past: desperately trying to rationalize the status quo.

‘Max, you wouldn’t marry me even if I wanted you to. If I left Casper. Would you?’

‘I’m not the marrying type, Gemma. The stay-at-home reliable husband …’

‘Not all women are like your mother,’ Gemma interrupted. ‘You don’t have to run away from all of us.’

Gemma had no idea how cruel her remark was. Max had never told her how or why his father died. So he couldn’t be angry with her now. He stood up from the bed and poured himself a large glass of Scotch.

‘Enough of this,’ he said lightly. ‘I want to take you out wearing my beautiful watch. At least if I run away from you tonight, I’ll be able to time myself.’

3

Amsterdam, six months earlier

Paul Wielart was a man of strict routine. Six days a week he arrived at his offices near the flower market at seven o’clock sharp. The bells of the local clock tower could have been timed to him turning the key in the door.

To the unknowing eye, his offices reflected the image of a dour accountant. It was well ordered, old fashioned and immaculately clean. You could straighten your tie in the reflection of the brass plate outside the front door. The black-and-white-squared marble floor gleamed in the hallway; as did the internal glass windows, which gave the offices a semi-open-plan feel.

Wielart’s private office, however, was a lair shut away behind a heavy oak door. With the exception of his long-serving battleaxe of an assistant, none of the staff ever set foot in there. And not many of the firm’s clients were permitted to grace the stiff brown leather chairs or the nineteenth-century velvet-upholstered chaise longue.

Wielart was a small, unimposing man. He wore a suit and tie every day of his life and a black homburg whenever he set foot outdoors. In his early twenties, he had married a cousin, who was glad to have a prosperous husband and knew her place. They had one daughter, Josebe, who’d never done anything wrong, but hadn’t done much right either.

Having inherited the company from his father, together with a steady stream of respectable but mundane clients, Wielart quickly learnt that there were people who would pay extremely good money to have their accounts ‘organized’ and certified by a respectable accountancy firm.

Wielart bought his clients businesses on whose balance sheets cash could appear. Hotels, clubs and restaurants were initially his stock in trade. And then Wielart was introduced to Jorgan Stam.

Stam dealt in pretty well anything that was illegal. He’d started by trafficking prostitutes from Eastern Europe and then got into ‘hard’ drugs. The casino that he now owned – the Dice Club – had a rigged roulette table and only catered for losers. Any half-serious player was thrown out. Whatever Stam touched threw off cash.

It hadn’t taken Stam long to persuade Wielart that it would be in both their interests to team up. Wielart would keep the façade of his accountancy business going but devote his skill and energy to legitimizing Stam’s money trail. A fifty-fifty partnership, which Stam assumed would bind them inextricably together.

Wielart added a whole layer of supply companies to their operation. One of them, a vegetable retail business, turned over in excess of a million euros per annum. And yet it never so much as handled a sprig of broccoli.

The hotels and restaurants that bought these fictitious vegetables marked them up three hundred per cent, as the taxman expected, and sold them on to their customers – the vast majority of whom happened to be cash buyers.

The profits that all of these businesses made appeared to be legitimate. As did the money the vegetable farms made at the end of the chain. And their profits were constantly expanding.

There was some tax to be paid, but the bulk of the proceeds Wielart converted into more land or fresh businesses before the taxman got his hands on any liquid profits. And all the while he maintained the image of the dour accountant.

Wielart was the epitome of the respectable husband, though he cared little about his wife or daughter. He spent as little time at home as possible, and the rest of his hours behind his desk. His wife was plain, dull, excelled at nothing and appealed to few. Josebe took after her.

However, Francisca Deetman – Josebe’s only visible friend – was everything that Wielart’s daughter wasn’t. A brilliant linguist, the best violinist in the school, as well as their most athletic hockey player, Francisca was traffic-stoppingly beautiful and rode like an angel on horseback. Her long blonde hair cascaded over her shoulders and her deep blue eyes paralysed men in the rare moments when she overcame her natural shyness and looked them in the eye.

Wielart wasn’t interested in women, per se. But the sixteen-year-old Francisca stirred something in him. And he started to make sure he was at home when Francisca was coming over.

She didn’t say much to him, but whenever he asked her about her father’s shipping company, she not only knew exactly what was going on, but could articulate it with the precision of a financial journalist. As she got to know him, she began to look him in the eye when she spoke to him. It stirred a feeling deep inside him that he knew was wrong, though he soon became a slave to it.

Francisca came on Wielart family holidays over the next two years. She played and read and sang with Josebe. In fact, they were utterly inseparable.

By the time Francisca was eighteen, Wielart was totally infatuated with her. He couldn’t be in the same room as her without darting a glance at her from behind his thick, round glasses whenever he thought no one would notice. She now had the body of a woman, not a girl, and he longed to see it, to touch it, to smell it. Occasionally, feigning innocence, he would walk into Josebe’s room at an inopportune moment in the hope of catching a glance of Francisca in a state of semi-undress. But he never had any success.

Wielart’s long-held aversion to swimming – his father had fervently believed that professionals must never risk being seen by their clients in anything other than a suit and tie – had robbed him of any chance to see Francisca in a bathing costume. All he could do was lust after her with growing desperation, while concealing his obsession with mounting self-loathing.

Pallesson made the short journey from The Hague to Amsterdam by train. Having deliberately left an hour’s slack in his schedule, he headed southeast across the Centraal Station concourse rather than taking a more direct route to his assignation through the Magna Plaza.

As he walked past the magnificent spires of St Nicolaaskerk, Pallesson didn’t have a religious thought in his mind. Far from it. In fact, the anticipation of the little treat he was about to give himself was making his armpits wet. He could feel the beads of sweat dripping down his ribcage.

A cold smile creased his face as he turned down the Oudezijds Achterburgwal. He looked approvingly at the swans gliding with menace along the canal – patrolling territory that stretched deep into the red-light district.

Pallesson hesitated as he walked past the first row of girls displaying themselves in the window, beckoning to him with their fingers. They beckoned to everyone. They had to. The only way they made any money was if they could earn more than the cost of the window they hired by the hour.

The top end of the red-light district offered the cheapest girls. They catered for a diverse range of tastes. Pallesson loved the illusion the windows gave that they were locked in cells. Animals in cages.

Like most bullies, he wasn’t naturally brave. So it took him a few metres to slow his walk until he finally stopped by the window of a small brunette desperately trying to entice him. He laughed at her. She took no notice and kept beckoning to him. And he kept laughing. He was safe. What was she going to do about it?

After a few seconds, he moved further down the street, buoyed up by his entertainment. He felt empowerment coursing through his veins. His next target was an Asian girl. She was pretty, smiley and had a great body. Pallesson stood in front of her window with his arms crossed. A dark frown crossed his face, as if something was concerning him. He fixed the girl with his cold, grey eyes, and shook his head. The girl kept smiling and opened her door ajar to encourage him.

‘Fifty euros for good time,’ she said. ‘Fifty euros.’

He gestured with his hand to dismiss her – though it wasn’t as if she was going anywhere – and moved on.

A hundred metres further along the pavement Pallesson turned down a narrow side street. An observant tourist would have noticed that all of the windows in the alley either had a whip hanging inside the window, or a small card proclaiming S&M. Pallesson checked his watch. He had forty-five minutes.

The curtains of the first two windows were shut. He wasn’t bothered. He’d used them both over the last few months. He wanted to try the last girl on the left. He’d noticed her before. She was large, strong-looking and, with any luck, German.

He was nearly shaking with excitement as he approached her window. The curtain was open. She was sitting on a high stool, talking to someone on her mobile phone. He caught her eye, expectantly. Unlike the other girls, she didn’t rush to open her door or beckon to him. She just carried on with her conversation and made him stand in the narrow alley like a prick. He felt demeaned. He was now desperate to have her.

She knew what she was doing. This little jerk wasn’t going anywhere. And she could see by the way he was dressed that she could up her charges. In her own time she opened the door and gestured with her head for him to enter. He stepped into her narrow window without saying a word. She drew the curtains behind him.

He left half an hour later, but without the shifty look that most of the punters had when they stepped quickly back on to the street and walked one way or the other, trying to blend into the general crowd. He liked being in control, not skulking about.

He checked his watch again. He had ten minutes to get to the jetty in the Oude Turfmarkt. He walked briskly along the canal past the magnificent houses that border the red-light district, making a mental note of the one he would like to live in. He then cut through the university campus, which brought him out opposite the Hotel de l’Europe. As he walked down the street he could hear the clock tower across the canal by the flower market chiming noon. He was bang on time. As he always was.

The old merchant’s boat waiting to pick him up was tied to the jetty used by the tourist boats.

‘Good morning,’ he said to one of the thickset lumps of muscle standing on the jetty.

The man barely registered his presence.

‘Let’s go,’ Pallesson said, unfazed.

The small boat had one cabin with a long narrow table and bench seats either side. One of the thugs shut the double doors behind him without so much as a word. He was now trapped in his own glass-sided cell, looking out on to the canal as the boat pulled away from the jetty.

Wevers van Ossen was the proprietor of the old merchant’s boat. He was also a vicious psychopath. And leader of the Kalverstraat gang, which was notorious for its brutality. For over a decade he’d been running a ruthless protection racket in Amsterdam.

His authority, however, was now being challenged by Eastern European gangs who were prepared to stand their ground. And one Dutchman – Jorgan Stam. The level of violence employed by Stam’s men was escalating fast. The balance of power was being tested.

So van Ossen had made a strategic decision. He was diversifying into drugs. It was simple for him. There were any number of desperate ‘mules’ prepared to take the risk of bringing heroin to Amsterdam by boat or land. All he had to do was warehouse and redistribute it. At no risk, given his position in Amsterdam. He’d ‘protected’ the docks for years. And Pallesson was the conduit and fixer for his first deal into England.

The two minders on van Ossen’s boat could have been twins, with their shaven heads and wide noses. Both were reckless killers. They’d left behind their birth names when they walked out the back door of the garrison at Doorn, Utrecht, and assumed the new identities that van Ossen had created for them: Fransen and Piek.

As members of the Dutch Maritime Special Operations Forces (MARSOF), they had come through the most brutal of training regimes in every extreme terrain possible; and thrived on it.

During their tour of duty at Camp Smitty near As Samawah in Southern Iraq, they had fought in conjunction with AH-64 attack helicopters, clearing out subversives. They had put their lives on the line for the Coalition forces and their British commander. And they had bailed out wounded British troops, pinned down by sniper fire. Their heroics had gone well beyond the call of duty, and because of this the British had covered up for them.

Fransen and Piek had gone off-piste while on patrol in a village called al-Khidr. They had told their Dutch compatriots to turn a blind eye and cover their backs while they cleared up a small matter.

The small matter was a meeting of six civilians in a house on the edge of the village. Six civilians who, their informants had told them, were collaborating with those still loyal to the Republican Guard.

Fransen and Piek wanted to send a message to the other villagers. A message that reminded them they should work with the Coalition forces, not the insurgents, if they valued their lives.

The six men, who were all unarmed, didn’t have time to react. They were shot dead with the Glock 17 sidearms that the Dutchmen were carrying. But that in itself would not have been a strong enough deterrent to the other villagers, desensitized as they were by the ravages of war. So Fransen and Piek cut off their victims’ heads and lined them up outside the house.

There was no concrete evidence that the two Dutchmen were the perpetrators of this crime. The British commander had two options: either to bust them and put them through the military’s disciplinary system, or to lose them fast. He chose the latter option. Within twenty-four hours the pair of them had been secreted back to Doorn garrison. It was their good fortune that the al-Khidr atrocity would be wiped from the record. As indeed would they.

Doorn’s sergeant major had long been van Ossen’s recruitment officer. The arrangement suited the military as much as it did van Ossen. He took embarrassing situations off their hands, and in return got the hardest recruits on the block. Van Ossen would be a hard man to usurp as long as this was the case. A fact that was not wasted on Pallesson.

Pallesson watched a large tourist boat passing them in the opposite direction. It was packed full of stereotypical sightseers. Some of them gawped at him as they glided past. He ignored them.

They passed the big, ugly Stadhuis-Muziektheater, built on the old Jewish quarter, then turned left by the Hermitage museum. Pallesson had no idea where they were going. Finally, they doubled back into a smaller canal and pulled over by some houseboats.

Van Ossen stepped aboard one of them, aided by another sour-looking bodyguard, and climbed down into the glass-sided cabin.

‘Good to see you again, Mr Pallesson. I hope you don’t mind a little ride on the canal. Do you like my boat? It was originally owned by a merchant, who used it to entertain his clients. Sadly, we had a little disagreement and he forfeited the boat. We don’t have time for entertainment right now. Maybe one day.’

‘That would be nice.’

‘So, are you still in? You have the painting for me?’ van Ossen asked bluntly.

‘Everything is in order, I can assure you.’ Pallesson was ruffled, but he kept his voice even. ‘I’ll have the painting next week. As agreed.’

‘I want to bring the deal forward. End of this week.’

Pallesson had dealt with van Ossen’s kind before. They liked to push people around. Partly to show they could, but also to protect themselves by changing locations, times. The only option was to stand up to them.

‘That isn’t possible,’ Pallesson said calmly. ‘Barry Nuttall won’t have the money by then. And I personally guaranteed that The Peasants in Winter would be our bond. It can’t be extracted until next week – I can’t hand it over until then – that was our agreement.’

‘So how do I know you’re good for the deal?’

Van Ossen was irritated. And reluctant to sit on the drugs a day longer than he had to.

‘Our deal is agreed. Barry Nuttall will bring over two million euros in used notes.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘I’ve done five deals as his partner – Russia and Turkey – never a problem. He’s a pro.’

Van Ossen was renowned for his explosive temper. He was not someone you wanted to cross, a fact that many unfortunate associates had reflected upon as they were sinking to the bottom of a pitch-black canal. In spite of the cashmere overcoat and dark-blue suit, it was obvious which side of the tracks van Ossen came from.

‘He better be,’ van Ossen said with as much malice as he could muster.

Most people would have been unnerved by an irritated van Ossen. Not Pallesson. Faced with danger and threat, he had learnt to draw strength from the dark forces that he believed watched over him.

So a drug-running Dutchman didn’t bother him. He was quickly back on the front foot.

‘You know who I’ve dealt with in the past. Never a problem. And I think you’ll find I’ll be useful across several areas of your supply chain. Especially with the UK borders tightening up,’ Pallesson said, holding his composure. ‘We’ll be ready next week. And then the beautiful Brueghel will be yours to treasure for a few days.’

The Hague

Max breezed straight off the plane from Nice and strolled into the British Embassy in The Hague as if he owned the place. It was a surprisingly drab set-up. Three months earlier, when he’d first arrived from Moscow, Max had been expecting something much grander.

The semi-open-plan layout emphasized the seniority of some of its occupants. The ambassador had a large glass-fronted office with a secluded back room. Anyone else who merited private space got their own square glass box, which offered a degree of seclusion. Unfortunately, when Max had arrived, no ‘executive’ office had been available. So he’d had to muck in with the foot soldiers and take a desk in the open-plan area. This suited Max, as it gave him the chance to interact with the staff. It also secretly pleased Pallesson, underlining the chasm of importance that he believed had opened up between the two of them.