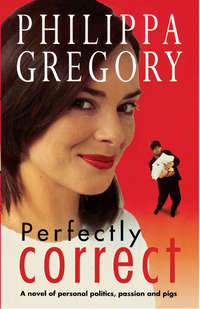

Perfectly Correct

Toby nodded. ‘We’d better hope she moves on then,’ he said. ‘Or we’ll have to do something about it.’

Louise was mollified at once by his use of the word ‘we’.

‘Are you coming back to dinner after the meeting?’

‘Miriam asked me. She said you were cooking.’

Toby nodded. ‘I thought I’d do lentil soufflé.’

‘Lovely.’

‘You could stay overnight. Perhaps your gypsy will be gone in the morning.’

It was not unusual for Louise to stay in Toby and Miriam’s spare bedroom. Meetings often went on late or, enjoying their company, she drank more wine than was safe if she were to drive home. A new tenant now lived in their studio flat which had been Louise’s home for six years. But she still felt a sense of ownership and comfort in the house. Although Louise and Toby never planned intercourse – they prided themselves on being spontaneous rather than calculating adulterers – Miriam always woke at seven and left the house at eight to be at her desk at eight thirty when the first bruised refugees from the night would start arriving. Toby and Louise never had to be at the university until ten. There was always time to make love, have a shower and eat a leisurely breakfast.

‘I might stay,’ Louise said unhelpfully.

One of the reasons behind her move to the country and a house of her own was a feeling that Toby’s sexual convenience was too well served by an attractive wife in his bed, and an attractive mistress in his upstairs flat. The arrangement had been of Louise’s own making – she had found them the house to buy and then suggested that she rent their studio flat – but after the illicit delight of the early months, she wondered if the chief beneficiary was Toby. His occasional affairs at the university, so prone to heartbreak and disaster, ceased. He no longer had to invent plausible late-night meetings to satisfy Miriam’s polite inquiries. He was no longer exposed to the risk of gossip among the undergraduates.

But his affair with Louise did not cramp his sexual style. If he was attracted to a woman at a conference they would sleep together, and he would tell Louise openly and frankly that he had done so. There was no reason for them to be monogamous lovers. It was only Louise who found that no-one pleased her as Toby did and that other encounters left her weepy and depressed. It was Louise, not Miriam, who dreaded Toby’s weekend conferences on ‘Vandalism and the Inner Cities’ or ‘Dependency Culture’. Miriam had the security of a contractual, property-sharing marriage. Louise sometimes feared that she was peripheral.

Even worse for Louise was that the chief beneficiaries of her arrangement were both Toby and Miriam. Louise did more than her share of housekeeping. She cooked meals for the three of them, she stayed at home to greet plumbers and electricians when Miriam had to be at work. When the married couple took their long summer holiday cycling in France, Louise maintained the house in their absence. Miriam’s outpouring of energy and care to the poor, the dispossessed and the victims of sexual violence left a vacuum in her marriage which would inevitably have been filled by another woman. Any woman other than her best friend would have tried to break up the marriage. But Louise, loving Miriam and desiring Toby, was the only woman in the world who would satisfy Toby’s errant sexuality without threatening Miriam’s position.

And Miriam, sexually satisfied and overworked, trusted her husband and her best friend to be as honourable and as straightforward as herself.

At first Louise had thought herself lucky. Her luxuriously frequent sex with Toby was unshadowed by guilt and did not exclude other possible partners. Her constant and long affection for Miriam deepened and grew as the three settled comfortably into their house together. But slowly Louise began to resent Miriam’s commitment to her causes and her absent-mindedness at home. Louise started to fear that at an unconscious level Miriam was glad to have Toby sexually served without threat to her marriage. This put an entirely different complexion on a love-affair which had been gloriously secret. If it were not clandestine, then it was not a hidden betrayal of Miriam but an open exploitation of Louise – and she hated the thought of that.

Then Louise’s aunt died, she inherited the cottage and chose independence. Toby advised her to stay in town, and even took the trouble to take her to see attractive sea-front flats. Louise suspected him of wanting to set their affair on a permanent and unchanging footing – with a wife at home and a mistress in a pretty little flat. Miriam advised her to stay in town, citing the need of a peer group, of sisterhood, and intellectual neighbours. Louise suspected them both of wanting to keep the comfortable status quo forever. She feared a life of half-marriage, half-spinsterhood, forever waiting on Toby’s free time, forever trying to please him, forever competing not only with Miriam but with younger and younger women. In the back of Louise’s mind was the hardly glimpsed thought, that without her in the house Toby and Miriam’s differences would surface and become insoluble. Their marriage, which from the start had been a three-legged stool, might topple and fall. Toby might leave Miriam for Louise; and the hidden issue of which woman was his favourite would be openly and finally resolved in her favour.

Toby tweaked a sleek lock of Louise’s hair. ‘Don’t tease,’ he said firmly. ‘Say if you’ll stay or not.’

Toby had lived with two feminists for all of his married life. He had never had to tolerate coquetry. He had never had to bear the uncertainty which most men learn to endure. ‘Make your mind up now,’ he insisted. ‘I need to know whether or not to put sheets on the spare bed.’

Louise responded at once to the voice of bracing nononsense comradeship and wilfully cast aside the centuries-old tradition of female manipulative power. ‘I’ll stay.’

Toby finished his drink. ‘I’ll get home to my cooking then. I’ll give you a lift. Are you meeting at the Women’s Centre?’

Louise finished her wine. ‘Thanks.’

They walked to the car park. In the shadowy interior of the car Toby reached for Louise and turned her face towards him. Her skin seemed very pale, almost translucent, her eyes a very dark brown, her hair silky and soft to the touch. Toby felt desire rise in him like a gourmet’s saliva when he anticipates a meal. There was something so exquisitely lavish about having two women under the same roof. Louise, since her move, was more precious to him than she had been before. He had been starting to take her for granted after nine years of domestic adultery. But now, when she came into town there was a scent of strangeness about her; she was a different woman and the philanderer in Toby rose to the challenge of novelty.

Louise rested her head against his palm and let his fingers trace the line of her temple, of her cheekbone. She had slept with half a dozen men during the course of her affair with Toby but not one touched her as Toby could do. When they made love, though they never said, they both listened for Miriam’s key in the lock, and feared her sudden unexpected return. It was a thought which would always bring them both to successful, mutual climax. It was a wholly secret affair: rich, even rancid, with adultery. Nothing else for Louise could equal that sexy frisson of betrayal and guilt.

‘You smell of outdoors,’ Toby said.

Louise smiled.

‘Let’s go up to the Downs,’ Toby suggested, cupping her face in his hand. ‘You can be late, can’t you?’

Miriam would never be late for a meeting. She allotted her time in tidy effective parcels.

Louise remembered this as she turned her lips to Toby’s warm palm and let herself lick and then nip him. ‘Yes,’ she said.

Miriam was chairing the Fresh Start committee meeting. She glanced up with irritation when the door of the committee room opened and Louise came in late and slightly flushed. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she apologised. ‘Car trouble.’

Miriam nodded. ‘We were discussing the number of entrants to the science and industrial courses,’ she said. ‘They’re not very satisfactory.’

Louise took her place between two women. On her left was a postgraduate student specialising in feminist studies, an earnest girl with cropped hair and deliberately plain glasses. On her right was Naomi Petersen, deputy head of the school of Sociology, elegantly dressed in a pale grey suit.

‘Our own background is dominated by the humanities,’ Naomi offered. ‘We’re probably not offering adequate models.’

Miriam nodded. ‘We need more women who work in technology and industry on the committee and especially at the open day.’

‘I suggested some months ago that we approach Sci/Ind direct and tell them the problem,’ Naomi said smoothly.

There was a visible stiffening around the table among the eight members. The engineering students were notorious for their hearty jovial behaviour. None of the women wished to seek help from that department believing that the professor, an industrial chemist of nearly sixty, was as likely to pinch their bottoms as his boyish undergraduates.

‘They’re not savages,’ Naomi snapped irritably. ‘They have a positive discrimination policy. Their problem is recruitment from the schools. Girls are discouraged from industry and engineering long before they consider their A levels.’

‘Perhaps we should work with local schools,’ Wendy Williams said softly from the end of the table. ‘Go to the source of the problem.’

‘But we want women undergraduates next year,’ Naomi replied.

‘And role models for open day,’ Miriam reminded them.

‘I don’t think that Sci/Ind is a very empathetic place,’ Josephine Fields remarked. Her enormous earrings clashed like temple gongs as she turned her head one way and then another. ‘They’re male dominated, their noticeboards are full of sexist jokes, in the workshops they have demeaning posters. I think we should campaign to change them, before we even consider encouraging women to attend. They’ve got to change. I don’t see why we should ask them for help.’

‘What exactly are these jokes and posters?’ Naomi demanded.

‘I’ve looked through the window,’ Josephine insisted. ‘They are offensive.’

Miriam glanced at the clock. ‘We have to take a decision on this and move on. Is there any way we can recruit local trained women for our open day? It’s very soon, remember.’

‘I don’t want this issue swept over,’ Josephine said. She stared at Miriam challengingly. ‘There’s no point in us meeting as women if we’re going to behave like men. I thought we were having a free discussion – not having to rush through a masculine-type agenda, in disciplined male-structured ways.’

‘I suppose we don’t want to be here all night,’ Naomi murmured softly. ‘Whatever gender the meeting is.’

Josephine rounded on her. ‘I suppose we want to be here as long as it takes to reach a consensus,’ she said. ‘Till the problem is solved in a consensual agreeing way. It is men who suppress discussion by imposing unnatural structures and time limits. I thought we were sensitive to natural and organic rhythms, not patriarchal and capitalistic timekeeping.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Miriam said shortly. She did not sound particularly sorry, she sounded exhausted and irritable. ‘I didn’t mean to be heavy-handed. I didn’t understand the complexity of this issue. I thought we were just trying to recruit more women scientists for the open day.’

‘I think there’s a wider issue about whether the Science department is capable of accommodating women students in large numbers,’ Josephine declared, joyfully widening the issue yet further. ‘I’m not happy about trying to recruit mature women students and sending them in there at all.’

‘The alternative is that they don’t go to university,’ Naomi said rather sharply. ‘Are we advising them to stay home and have children instead?’

Josephine flushed. ‘How can we recommend them to attend a course at this university when we know that the course is sexist?’

Naomi smoothed her hair at the back where it was drawn up into an elegant roll. ‘I don’t think we exactly know that, do we? We know that you’ve looked through the window and seen something you didn’t like. But has anyone been round the department? Does anyone know any students or tutors there?’

The women shook their heads in unanimous disapproval.

‘So what did you see that was so dreadful?’ Naomi demanded.

‘It was a very offensive calendar,’ Josephine said. ‘Advertising Unipart.’

Naomi gave an ill-concealed snort of laughter. ‘And what did it show?’

‘It was a picture of a half-naked woman astride a grossly enlarged spark plug,’ Josephine said doggedly. ‘Is anyone going to tell me that this committee believes that that is an acceptable image of women and technology?’

Naomi glanced at Miriam, inviting her to share the joke.

‘Perhaps we could speak to the head of the department,’ Miriam suggested wearily. ‘But I really think that it is important to recruit mature women students into the department.’

‘Into a place like that?’ Josephine demanded.

Wendy nodded in agreement with her. ‘They are openly showing pornography,’ she said quietly. ‘We know this encourages men to see women as sexual objects, and encourages violence against women. The statistics are very clear, Miriam. We can’t send women in there, it’s not safe.’

At the key words ‘sexual objects’ and ‘safe’ three other women nodded solemnly, their gigantic earrings clashing like cymbals. They had invoked a code as powerful as that of a Victorian drawing room where the word ‘improper’ once held the same power. No rational discussion could possibly follow the invoking of the word ‘safe’. If a woman knew she was not safe, thought she was not safe, or even fancied on entirely mistaken evidence that she was not safe, then nothing could be said to dissuade her from her fear. It was a key taboo, and its invocation marked the complete end of all reasonable debate. Miriam threw a despairing look at Louise.

Louise responded. ‘I’d be prepared to take a message to the head of Science/Industry from this committee, drawing the posters and noticeboards to his attention,’ she said. ‘If he’s prepared to take them down then perhaps we could feature his department in our open day. It’d show he was open to education. There must be women working in the department who might be prepared to come and represent the department at the open day.’

‘If there are women working in that environment then I think we should form a subgroup to discuss the issues with them,’ Josephine persevered. ‘They’re being bombarded with male obscenity every day of their working lives. We should be working with them.’

‘That’s two motions,’ Naomi observed, nodding at Miriam prompting her to move on.

Miriam shot her a look which was neither grateful nor sisterly.

‘Can’t we set up a women-only Science and Industry department?’ Wendy asked. ‘Housed in the same buildings but working alternate sessions. So that we train new women scientists and engineers by experienced women scientists and engineers in a safe and segregated environment.’

Naomi Petersen made a muffled exclamation. ‘We haven’t organised an open day yet, and we’ve been discussing it for twenty minutes! How the hell d’you think we’re going to organise an entirely new university department?’

Josephine smiled at her. ‘That’s a very negative attitude to Wendy’s interesting suggestion, Naomi,’ she said with slow triumph. ‘And a very unsupportive tone of voice. A lot of women’s groups have found that separate development solves many problems. I think we should consider Wendy’s very imaginative idea.’

Miriam rubbed her face as if struggling to stay awake. ‘Wendy, would you like to make a report on this, and bring it back to our next meeting, next Tuesday? And Louise, would you approach Sci/Ind and tell them our concern about their noticeboards? And Josephine, would you like to find out how many women are working at Sci/Ind already, staff and students, and we can then consider your idea for a subgroup at the next meeting?’

There was a rather disappointed consensus, but the most disaffected members had been skilfully lumbered with tasks and were reluctant to open their mouths for fear of incurring more chores. Miriam was no slouch in the chair. She glanced around the table. ‘Does anyone want to say anything more about this item?’ she invited. ‘Absolutely sure? OK. Next item is crèche provision at the university. Susan has a comment.’

Louise and Miriam walked home from the meeting. Louise carried some of Miriam’s box files. Both women were inwardly seething at the way the meeting had gone but neither could voice a personal attack against one of the sisterhood. It must be done; but it would have to be done in code.

‘I’m very concerned about Josie,’ Miriam began in a pleasant tone after they had walked for a while.

Louise glanced at her.

‘She seems very stressed,’ Miriam said. ‘Stressed’ was a codeword for behaviour which in conventional society would be regarded as unreason verging on insanity.

‘She is tense,’ Louise agreed. ‘Of course she has personal problems.’ Josephine’s long-term woman lover was a student in Naomi Petersen’s department and had briefly enjoyed a staggeringly glamorous fling with her. The open nature of Josie’s relationship and the general myth of feminist solidarity precluded any complaints when Naomi suddenly favoured the young woman, took her to London to see experimental theatre, kept her overnight at her Brighton flat, lent her books, cooked her meals, and then with equal suddenness sent her, reeling with delight and totally unmanageable, home to Josie.

Neither Louise nor Miriam would discuss other people’s sexual affairs. They adhered to the belief that these matters were private and that any curiosity was vulgar and prurient. Even when they were longing to dissect a piece of rich gossip their conversation had to be conducted in a code as arcane as that of an Edwardian parlour, and always had to indicate first and foremost their concern for the people involved. ‘Josie is bound to find it difficult to work with Naomi for a while,’ Miriam said. ‘Considering her relationship difficulties.’

Louise nodded. ‘I understand that Josie and Viv are talking about a trial separation – ever since Viv spent time with Naomi.’

Miriam widened her eyes but was too restrained to demand details. ‘That’s unfortunate.’

‘Viv seems to think that she may have a future with Naomi.’

‘Oh,’ Miriam said. ‘I wouldn’t have thought Naomi was ready for a commitment.’

‘Viv is very determined. I think she went round to Naomi’s flat and virtually camped on the doorstep.’

‘It’s good that she should ask for what she wants,’ Miriam said doubtfully. ‘But I don’t know if Naomi is right for her?’

‘And Naomi is going through a rather – er – unsettled phase,’ Louise offered. Miriam nodded, understanding that Naomi’s rampant promiscuity meant that no-one stayed more than a couple of nights in her elegant flat, and that Viv might force her way in, but would be swiftly bounced when the novelty wore off.

‘She’s rather brisk,’ Louise said. ‘I thought she wanted to chair the meeting instead of you.’

‘She’s welcome to it,’ Miriam said. ‘I have all the meetings I ever want. And things change so slowly!’

‘You do wonderful work,’ Louise said absent-mindedly. ‘I couldn’t do it.’

‘Your contribution is theory,’ Miriam reassured her. ‘Have you finished that essay on Lawrence yet? Sarah told me she was waiting for it.’

Louise thought of the word processor screen still empty of anything but the little winking cursor, and the van in her orchard. ‘How can I work? Every time I look out of the window I see this huge blue van and this mad woman in it with her horrible dog.’

Miriam glanced at her. The linked topics of madness and women were as taboo as the Unipart calendar. ‘Do you mean she is ill?’ she asked rather stiffly. ‘Has she been released for care in the community? Is she alone and unsupported?’

‘I didn’t mean mad, I meant independent.’ Louise retreated rapidly. ‘She wears something like fancy dress. She seems to be alone. And I can’t help but dislike the fact that she seems to know the neighbourhood and she has parked on my land without permission. There are plenty of other places she could go.’

‘If she’s not doing any damage…’

‘She’s invading my personal space.’

Miriam shot her a quick mocking smile. ‘I didn’t know your personal space went as far as several acres.’

Louise felt herself smiling guiltily in reply. ‘Well, you wouldn’t like it if it was your front garden,’ she said.

Miriam sighed. ‘It virtually is. The phone never stops ringing. I seem to be out every night at one meeting or another. If they all came and lived in a caravan in my garden it would be easier to manage.’

They turned in the gate of the tall terraced house. Miriam glanced up at the illuminated windows of the top flat. ‘Oh, Hugh’s in,’ she said. ‘He might eat with us.’

She opened the front door. A thin watery smell of cooking pulses greeted them. ‘Lentils again,’ Miriam remarked without pleasure. ‘Toby has bought a New Age cookbook. We haven’t had meat for weeks.’

Louise dumped Miriam’s box files on the hall table and went through to the kitchen. Toby was stirring orange porridge in a casserole dish. Louise put her arms around him from behind and hugged him, resting her cheek against the smooth blade of his shoulder.

‘I’m starving,’ she said. ‘It smells wonderful.’

Toby did not disengage himself as Miriam came into the kitchen. He smiled at her. ‘Hello, darling, three phone messages for you.’

Miriam nodded and went out to the telephone in the hall. Toby heard her pick up the phone and dial a number. Only then did he turn to Louise and kiss her deeply on the mouth. While his left hand stirred the lentils his right hand smoothed down from her neck across her breast and down to her buttock.

‘Lovely,’ Toby said. With Miriam and Louise under his roof again he felt wealthy as a polygamous sheikh.

Hugh was not invited to join them for dinner. Toby said he had not made enough. Hugh stayed upstairs, eating baked beans with a spoon from the saucepan, tantalised by the smell of hot food and by the sound of popping corks and laughter. Hugh was Miriam’s choice of lodger. She and Louise had together decided that another woman would not be suitable. Toby’s faint, unexpressed hope, that a second woman lodger might invite him into her flat and into her bed in the morning and at weekends when Miriam was working, was disappointed before he had even acknowledged it to himself.

Hugh was researching into marine life and kept strict office hours at his studies. On Friday and Saturday nights he would go out to a modern jazz club with friends from work and get seriously but quietly drunk. Toby in his heart rather envied these bullish excursions. Toby had no friends. Colleagues at the university feared and envied the speedy progress of his career. Women tended to pass through his life, not stay. The Men’s Consciousness group which he led on Thursday nights was an area of conscientious work rather than spontaneous pleasure. Too many of the men had sexual problems, too many of them would weep over their relationship with their father. Toby would facilitate their tears and their worries over the size of their genitals but he could not grieve with them.

He knew that Men’s Consciousness groups were a pale shadow of the real thing. In this area the women had the edge. Female consciousness had the pulse of an authentic revolutionary movement. Women had so much more to say. They were angry with their mothers, with their fathers, with their kids. They had issues to challenge about social treatment. They had two thousand years of repression to cite. Every week, every day, almost every moment they suffered from inequality and had to evolve a revolutionary response. Male consciousness was nothing more than a bandwagon attempt by the left-out kids somehow to join in the game. All the unconvincing inventions of male bonding and tenderness could not conceal the fact that men were solitary, rather stupid individuals while women were spontaneously sensitive and collectively minded. Female sexuality was Toby’s delight. Male sexuality held no interest for him whatsoever. Indeed he had to conceal distaste when his brothers wanted to hug him. Except for Miriam and Louise, Toby was a solitary man.