The Girl in Times Square

He was leaving, he was not coming back, and she was wearing black. Lily would have liked to clear her throat, say a few things, maybe convince him not to go, but again, she felt that the time for that had passed. When, she didn’t know, but it had passed all the same, and now nothing was left for her to do but watch him leave, and maybe chew on some stale pretzels.

Joshua was skinny and red-haired. Turning his muddy eyes to her, he asked, running his hand through his hair—oh how he loved his hair!—if she had anything better to do than to stand there and watch him. Lily replied that she didn’t, not really, no. She went and chewed on some stale pretzels.

She wanted to ask him why he was leaving, but unspoken between them remained his reasons. Unspoken between them much remained. His leaving would have been inconceivable a year ago: how could she handle it, how could she handle that well?

She stepped away from the wall, moved toward him, opened her mouth and he waved her off, his eyes glued to the television set. “It’s the Stanley Cup final,” was all Joshua said, one hand on his CDs, the other on the remote control with which he turned up the sound on the set, turning down the sound on Lily.

And to think that last week for her final paper, her creative-writing professor, as if the previous week’s obituary flagellation were not enough, gave them a topic of, “What would you do today if you knew that today were the last day of your life?”

Lily hated that class. She had taken it merely to satisfy an English requirement, but if she knew then what she knew now, she would have taken “Advanced Readings on John Donne” at eight in the morning on Mondays before creative writing on Wednesday at noon. Oh, the merciless parade of self-examination! First memory, first heartbreak, most memorable experience, favorite summer vacation, your own obituary (!), and now this.

All Lily fervently hoped at this moment was that today—breaking up with her college boyfriend—would not be the last day of her life.

Her apartment was too small for Sturm und Drang. The hallway served as the living room. In the kitchen the microwave was on top of the only flat counter surface and the drainer was on top of the microwave, dripping the rinsed-out Coke cans into the sink, half of which also served as storage for moldy bread—they did not eat on regular plates; they barely ate at home. There were two bedrooms—hers and Amy’s. Tonight Lily went into Amy’s room and lay down on Amy’s bed, consciously trying not to roll up into a ball.

During the commercial, Joshua got up off the couch for a drink, glanced in on her and said, “You think you could sleep with Amy? I’m going to have to take my bed back. I’d leave it, but then I’ll have nowhere to sleep.”

Lily wanted to reply. She thought she might have something witty to say. But the wittiest thing she could think of was, “What, doesn’t Shona have a bed?”

“Don’t start that again.” He walked into the kitchen.

Lily rolled up into a ball.

Joshua paid a third of the rent. And still she was broke, her diet alternating between old pretzels and Oodles of Noodles. A bagel with cream cheese was a luxury she could afford only on Sundays. Some Sundays she had to decide, newspaper or bagel.

Lily used to read her news online, but now she couldn’t afford the twenty bucks for the Internet connection. So there was no Internet, no bagel, and soon no Joshua, who was leaving and taking his bed and a third of the rent with him.

If only she had had the grades to get into New York University downtown instead of City College up on 138th Street. Lily could walk to school like she walked to work and save herself four dollars a day. That was twenty dollars a week, $80 a month. $1040 a year!

How many bagels, how much newspaper, how much coffee that thousand bucks could buy.

Lily was paying nearly $500 a month for her share of the rent. Well, actually, Lily’s mother was sending her $500 for her share of the rent, railing at Lily every single month. And coming this May, on the day of her purported, supposed, alleged graduation, Lily was going to get her last check from the bank of mom. Without Joshua, Lily’s share would rise to $750. How in the world was she going to come up with an extra $750 come June? She was already waitressing twenty-five hours a week to pay for her food, her books, her art supplies, her movies. She would have to ask for another shift, possibly two. Perhaps she could work doubles, get up early. She didn’t want to think about it. She wanted to be like Scarlett O’Hara and think about it tomorrow—in another book, some fifty years down the line.

The phone rang.

“Has he left, mama?” It was Rachel Ortiz—Amy’s other good friend, maybe even best friend, she of the sudden ironed blonde hair and the perpetual blunt manner. Someone needed to explain to Rachel that just because she was Amy’s friend, that did not automatically make her into Lily’s friend.

“No.” Lily wanted to add that watching the Stanley Cup was slowing Joshua down.

“That bastard,” Rachel said anyway.

“But soon,” said Lily. “Soon, Rach.”

“Is Amy there?”

“No.”

“Where is she? On one of her little outings?”

“Just working, I think.”

“Well, tomorrow night I don’t want you to stay in by yourself. We’re going out. My new boyfriend wants to take us to Brooklyn, to a nightclub in Coney Island.”

“To Coney Island—on Monday?” And then Lily said, “I’m not up to it. It’s a school night.”

“School, schmool. You’re not staying in by yourself. You’re going out with me and Tony.” Rachel lowered her voice to say TOnee, in a thick Italian accent. “Amy might come, too, and she’s got a friend for you from Bed-Stuy, who she says is a paTOOtie.”

“Oh, for God’s sake!” Lily lowered her voice to a whisper. “Joshua’s still here.”

“That bastard,” said Rachel and hung up.

“What, is Rachel trying to fix you up already?” Joshua said. “She hates me.”

Lily said nothing.

That night, after the Stanley Cup was over, up and down the five flights of stairs Joshua traipsed, taking his boxes, his crates, his bags to Avenue C and 4th Street, where he was now staying with their mutual friend Dennis, the hairstylist. (Amy had said to her, “Lil, did you ever ask yourself why Joshua would so hastily move in with Dennis? Did you ever think maybe he’s also gay?” and Lily replied, “Yes, well, don’t tell me, tell that to Shona, the naked girl from upstate New York he was calling on my phone bill.”)

Who was going to cut Lily’s hair now? Dennis had always cut it in the past. Why did Joshua get to inherit the haircutter? Well, maybe Paul, who was Amy’s other best friend, and a colorist, knew how to cut hair. She’d have to ask him.

Joshua had the decency not to ask her to help him, and Lily had the dignity not to offer.

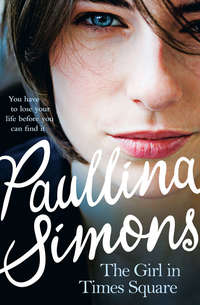

Around 3:00 a.m., he, with his last box in hand, nodded to her, and then left, rushing past her The Girl in Times Square, her only ever oil on canvas that she had done when she was twenty and before she met Joshua.

“There are things about you I could never love,” Joshua had said to Lily two days ago when all this started to go down on the street.

“If I knew that today were the last day of my life, I’d want to be like the girl in the famous postcard, being thrown back in the middle of Times Square, kissed with passion by a stranger when the war was over.

Except—that isn’t me. That is somebody else’s fantasy of a girl in Times Square. Perhaps it’s Amy. But it’s a fraudulent Lily.

The real Lily would sleep late, until noon at least, with no classes and no work. And then, since the weather would be warm and sunny on her last day, she would go to the lake in Central Park. She would buy a tuna sandwich and a Snapple iced tea, and a bag of potato chips, and bring a book she was re-reading at the moment—Sula by Toni Morrison—slowly because she had time, and her notebook and pencils. She would spend the afternoon sitting, eating her food, drawing the boats, and Sula’s Ajax—with whom she was perversely in love—reading, thinking about what to render next. She’d have a long sit-and-sketch on the rocks and on the way home at night she would go to Times Square pushing past all the people and stand against the wall, looking at the color billboards animating and the towers sparkling, red green traffic lights changing and blue white sirens flashing, the yellow cabs whizzing by. The naked cowboy standing in the street, playing his guitar in his hat and underwear, and the families, the children, the couples, the young and the old, lovers all, taking pictures, laughing, crossing against the lights.

This girl in Times Square stands by the wall while others cross against the light.”

Lily turned away from the door and stared out the open window into the night, on Amy’s bed, alone.

Allison Quinn

There once was a woman who lived for love. Now she stood and stared out her window. Outside she saw green palms and red rhododendrons and a blue sky and an aqua ocean and gray cliffs and black volcanoes and white sands. She did not look inside her room. She was waiting for her husband to come back from buying mangoes. It was taking him forever. She moved the curtain slightly out of the way to catch a movement outside, and sighed, remembering once upon a time when she was young, and had dreamed for the sky and the sea and plenty.

And now she had it.

And once a man put on a record on an old Victrola and took her dancing through their small bedroom. The man was handsome, and she was beautiful, and they spoke a different language then. “The look of love is in your eyes … ” Now the man went for walks by himself under the palms and over the sands. He wet his feet in the ocean and his soul in the ocean too, and then he walked to the fruit stand and bought the juicy mangoes, and the perky salesgirl said they were the best yet, and he glanced at her and smiled as he took them from her hand.

The woman stepped away from the window. He was always walking, always leaving the house. But she knew—he wasn’t leaving the house, he was leaving her. He just couldn’t stand the thought of being with her for an hour alone, couldn’t stand the thought of doing something she wanted instead of everything he wanted. When she didn’t do what he wanted, how he sulked—like a baby. That’s all he was, a baby. Do it my way or I won’t talk to you, that was him. Well, could she help it if mornings were not the best time for her? Could she help it that in the mornings she could not get up and go for a walk and a swim in all that sunshine. It depressed her beyond all sane measure that at eight in the morning the ocean was so warm, the sun was so strong. If only it would rain, just once! She was done with that damn ocean. And that sun. Those mangoes, that tuna sashimi, that volcanic ash. Done with it.

She bought heavy room-darkening curtains and drew them tight to keep out the day, to make believe it was still night.

She made believe about a lot these days.

She couldn’t understand, where was he? When was he going to grace her with his presence? Didn’t he know she was sick, she was hungry? Didn’t he know she had to eat small meals? That’s just it, he didn’t care what she needed, all he cared about was what he needed. Well, she wasn’t going to put a single bite in her mouth. If she fainted from low blood sugar and broke a bone, so much the better. She’d see how he felt then, that he was out all morning and didn’t make his sick wife breakfast. She’d see how he’d explain that one to her mother, to their kids. She’d be damned if she put a spoon of sugar into her mouth.

The bedroom door opened slightly. “I’m back. Have you eaten?”

“Of course I haven’t eaten!” she spat. “Like you even care. I could croak here like a rat, while you’re glibly walking in your fucking Maui without a single thought for me!”

… a look that time can’t erase …

Silently the door closed, and she remained in her darkened room with the drawn shades in the ginger Maui morning, alone.

A Man and a Woman

It’s late Friday night and they’re in her apartment. They had been to dinner, she invited him for a drink and dancing in a wine bar near where she lives. He said no. He always says no—drinking and dancing in wine bars is not his strong suit—but you have to give it to her—she’s plucky. She keeps on asking. Now they’re in her bed, and whether this is his strong suit, or whether she has no more attractive options, he doesn’t know but she’s been showing up every Friday night, so he must be doing something right, though he’d be damned if he knows what it is. The things he gives her, she can get anywhere.

And after he gives them to her, and takes some for himself, she falls contentedly asleep in the crook of his arm, while he lies opened-eyed and in the yellow-blue light coming from the street counts the tin tiles of her tall ceiling. He may look content also—in tonight’s ostensible enjoyment of his food and his woman—to someone who has observed him scientifically and empirically, wholly from without. But now in a perversion of nature, the woman is asleep and the man is staring at the ceiling. So what is in him wholly from within?

He is counting the tin tiles. He has counted them before, and what fascinates him is how every time he counts them this late at night, he comes up with a different number.

After he is sure she is asleep, he disentangles himself, gets up off the bed, and takes his clothes into the living room.

She comes out when his shoes are on. He must have jangled his keys. Usually she does not hear him leave. It’s dark in the room. They stare at each other. He stands. She stands. “I don’t understand why you do this,” she says.

“I just have to go.”

“Are you going home to your wife?”

“Stop.”

“What then?”

He doesn’t reply. “You know I go. I always go. Why give me a hard time?”

“Didn’t we have a nice evening?”

“We always do.”

“So why don’t you stay? It’s Friday. I’ll make you waffles for breakfast.”

“I don’t do waffles for Saturday breakfast.”

Quietly he shuts the door behind him. Loudly she double bolts and chains it, padlocking it if she could.

He is outside on Amsterdam. On the street, the only cars are cabs. The sidewalks are empty, the few barflies straggle in and out. Lights change green, yellow, red. Before he hails a taxi back home, he walks twenty blocks past the open taverns at three in the morning, alone.

PART I

IN THE BEGINNING

You call yourself free? Free from what? What is that to Zarathustra! But your eyes should announce to me brightly: free for what?

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

1

Appearing To Be One Thing When it is in Fact Another

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

And again:

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

Reality: something that has real existence and must be dealt with in real life.

Illusion: something that deceives the senses of mind by appearing to exist when it does not, or appearing to be one thing when it is in fact another.

Miracle: an event that appears to be contrary to the laws of nature.

49, 45, 39, 24, 18, 1.

Lily stared at the six numbers in the metro section of The Sunday Daily News. She blinked. She rubbed her eyes. She scratched her head. Something was not right. Amy wasn’t home, there was no one to ask, and Lily’s eyes frequently played tricks on her. Remember last year in the delivery room when she thought her sister gave birth to a boy, and shouted ‘BOY!’ because they all so wanted a boy, and it turned out to be another girl, the fourth? How could her mind have added on a penis? What was wrong with her?

Leaving her apartment she went down the narrow corridor to knock on old Colleen’s door in 5F. Fortunately Colleen was always home. Unfortunately Colleen, here since she was a young lass during the potato famine, was legally blind, as Lily to her dismay found out, because Colleen read 29 instead of 49, and 89 instead of 39. By the time Colleen finished with the numbers, Lily was even less sure of them. “Don’t worry about it, me dearie,” said Colleen sympathetically. “Everyone thinks they be seeing the winnin’ numbers.”

Lily wanted to say, not her, not she, not I, as ever just a smudge in the reflected sky. I don’t see the winning numbers. I might see penises, but I don’t imagine portholes of the universe that never open up to me.

Lily was born a second-generation American and the youngest of four children to a homemaker mother who always wanted to be an economist, and a Washington Post journalist father who always wanted to be a novelist. He loved sports and was not particularly helpful with the children. Some might have called him insensitive and preoccupied. Not Lily.

Her grandmother was worthy of more than a paragraph in a summary of Lily’s life at this peculiar juncture, but there it was. In Lily’s story, Danzig-born Klavdia Venkewicz ran from Nazi-occupied Poland with her baby, Lily’s mother, across destroyed Germany. After years in three displaced persons camps, she managed to get herself and her child on a boat to New York. She had called the baby Olenka, but changed it to a more American-sounding Allison, just as she changed her own name from Klavdia to Claudia and Venkewicz to Vail.

Lily lived all her life in and around the city of New York. She lived in Astoria, and Woodside, and Kew Gardens, and when they really moved up in the world, Forest Hills, all in the borough of Queens. Her dream was to live in Manhattan, and now she was living it, but she had been living it broke.

When George Quinn, who had been the New York City correspondent for the Post, was suddenly transferred down to D.C. because of cost-cutting internal restructuring, Lily refused to go and stayed with her grandmother in Brooklyn, commuting to Forest Hills High School to finish out her senior year. That was some wild year she had without parental supervision. Having calmed down slightly, she went to City College of New York up on 138th Street in Harlem partly because she couldn’t afford to go anywhere else, her parents having spent all their college savings on her brother—who went to Cornell. Her mother, fortunately guilt-ridden over going broke on Andrew, paid Lily’s rent.

As far as the meager rations of youthful love, Lily, too quiet for New York City, went almost without until she found Joshua—a waiter who wanted to be an actor. His red hair was not what drew her to him. It was his past sufferings and his future dreams—both things Lily was a tiny bit short on.

Lily liked to sleep late and paint. But she liked to sleep late most of all. She drew unfinished faces and tugboats on paper and doodles on contracts, and lilies all over her walls, and murals of boats and patches of water. She hoped she was never leaving the apartment because she could never duplicate the work. She had been very serious about Joshua until she found out he wasn’t serious about her. She read intensely but sporadically, she liked her Natalie Merchant and Sarah McLachlan loud and in the heart, and she loved sweets: Mounds bars, chocolate-covered jell rings, double-chocolate Oreos, chewy Chips-Ahoy, Entenmann’s chocolate cake with chocolate icing, and pound cake.

One of her sisters, Amanda, was a model mother of four model girls, and a model suburban wife of a model suburban husband. The other sister, Anne, was a model career woman, a financial journalist for KnightRidder, frequently and imperfectly attached, yet always impeccably dressed. Her brother, Andrew, Cornell having paid off, was a U.S. Congressman.

The most interesting things in Lily’s life happened to other people, and that’s just how Lily liked it. She loved sitting around into the early morning hours with Amy, Paul, Rachel, Dennis, hearing their stories of violent, experimental love lives, hitchhiking, South Miami Beach Bacchanalian feasts. She liked other people to be young and reckless. For herself, she liked her lows not to be too low and her highs not to be too high. She soaked up Amy’s dreams, and Joshua’s dreams, and Andrew’s dreams, she went to the movies three days a week—oh the vicarious thrill of them! She meandered joyously through the streets of New York, read the paper in St. Mark’s Square, and lived on in today, sleeping, painting, dancing, dreaming on a future she could not fathom. Lily loved her desultory life, until yesterday and today.

Today, this. Six numbers.

And yesterday Joshua.

Ten good things about breaking up with Joshua:

10. TV is permanently off.

9. Don’t have to share my bagel and coffee with him.

8. Don’t have to pretend to like hockey, sushi, golf, quiche, or actors.

7. Don’t have to listen to him complaining about the short shrift he got in life.

6. Don’t have to listen about his neglectful father, his nonexistent mother.

5. Don’t have to get my belly button pierced because he liked it.

4. Don’t have to stay up till four pretending we have similar interests.

3. No more wet towels on my bed.

2. Don’t have to blame him for the empty toilet roll.

And the number one good thing about breaking up with Joshua:

1. Don’t have to feel bad about my small breasts.

Ten bad things about breaking up with Joshua:

10. There

9. Are

8. Things

7. About

6. You

5. I

4. Could

3. Never

2. Love.

Oh, and the number one bad thing about breaking up with Joshua …

1. Without him, I can’t pay my rent.

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

Her hair had been down her back, but last week after he left Lily had sheared it to her neck, as girls frequently did when they broke up with their boyfriends. Snip, snip. It pleased Lily to be so self-actualized. To her it meant she wasn’t wallowing in despair.

Barely even needing to brush the choppy hair now, Lily threw on her jacket and left the apartment. She headed down to the grocery store where she had bought the ticket. After going down four of the five flights, she trudged back upstairs—to put her shoes on. When she finally got to the store on 10th and Avenue B, she opened her mouth, fumbled in her pocket, and realized she’d left the ticket by the shoe closet.

Groaning in frustration, tensing the muscles in her face, Lily grimaced at the store clerk, a humorless Middle Eastern man with a humorless black beard, and went home. She didn’t even look for the ticket. She saw the mishaps as a sign, knew the numbers couldn’t have matched, couldn’t have. Not her lottery ticket! She lay on Amy’s bed and waited for the phone to ring. She stared out the window, trying to make her mind a blank. The bedroom windows faced the inner courtyard of several apartment buildings. There were many greening trees and long narrow yards. Most people never pulled down the shades on the windows that faced inward. The trees, the grass were perceived to be shields from the world. Shields maybe from the world but not from Lily’s eyes. What kind of a pervert stared into other people’s windows anyway?

Lily stared into other people’s windows. She stared into other people’s lives.

One man sat and read the paper in the morning. For two hours he sat. Lily drew him for her art class. She drew another lady, a young woman, who, after her shower, always leaned out of her window and stared at the trees. For her improv class, she drew her favorite—the unmarried couple who in the morning walked around naked and at night had sex with the shades up and the lights on. She watched them from behind her own shades, embarrassed for them and herself. They obviously thought only the demons were watching them, judging from the naughty things they got up to. Lily knew they were unmarried because when he wasn’t home, she read “Today’s Bride” magazine and then fought with him each Saturday night after drinking.