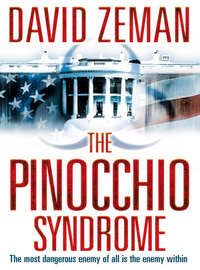

The Pinocchio Syndrome

‘What I really need is a cigarette,’ she said. ‘These hospitals are too strict about smoking.’

Kraig nodded. ‘The world is tough on smokers nowadays.’

‘Did you ever smoke?’ she asked him.

‘In high school,’ he said. ‘I quit when I got to college.’

Karen nodded, glancing at the thick wrists emerging from his suit jacket. His fingers were square, almost stubby. The backs of his hands were broad. She guessed he worked out, perhaps too much.

‘How did you get into the federal agent business?’ she asked.

He smiled, reflecting that it was indeed a business, like any other.

‘I was young, I had just gotten married. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life, and we needed money,’ he said. ‘A friend of mine was an FBI agent, and he told me about the salary and the benefits. From there, things just evolved.’

‘Are you still married?’ she asked.

He shook his head. She recognized the slight curl of his lip as the outward disguise of a pain he didn’t like to talk about. It was a look she had seen on her own face in the mirror.

He struck her as a straight arrow, but not as shallow. He looked like he had been around, made his share of mistakes. She liked that in him.

‘How about you?’ he asked. ‘How did you get into the reporting business?’

‘I always wanted to be a reporter,’ she said. ‘Even in high school. It keeps you busy. You meet a lot of people.’

‘People who aren’t necessarily glad to see you,’ Kraig added.

‘That’s right,’ she said, nodding. ‘But at least it gets you out of the house. I’m not that fond of my own company.’

She took a bite of her tuna sandwich, grimaced, and drank a swallow of coffee. ‘Jesus,’ she said. It had been years since she tasted food this bad, even on an airplane.

Kraig smiled understandingly.

She switched to the granola bar and ate half of it before saying what was on her mind.

‘It’s the same thing, isn’t it?’ she asked.

‘What?’

‘The same disease,’ she said. ‘The same as Everhardt.’

Kraig gave her a steady look.

‘You don’t listen, do you?’ he said. ‘No comment.’

‘On background?’ She smiled. ‘Off the record?’

He shook his head.

She was watching Kraig closely.

‘All vital functions normal,’ she said. ‘But the patient can’t act. Can’t obey simple commands, can’t talk, can’t walk, can’t feed himself. A paralysis of the function of action or decision.’

Kraig said nothing.

‘They’re looking for a vector,’ Karen said. ‘But they don’t really have a disease, so the vector may not help. There is no known disease that produces these symptoms.’

Kraig asked, ‘How do you know?’

‘I never reveal my sources.’ She shrugged.

‘Anyway, as it happens, I know a little something about this sort of thing. I did a double major in biochemistry and journalism in college. I’ve done a lot of reporting on diseases. This is definitely something new.’

Kraig shrugged. ‘If you say so. I’m not a doctor.’

She leaned forward, a hint of her clean-smelling cologne reaching Kraig, who smiled slightly.

‘Out here there are hundreds of victims,’ she said. ‘Each area is covered completely. But in Washington there is only one victim. The vice president of the United States.’

Kraig kept his poker face. But he knew she was right. If Everhardt had the same disease, dozens of others in Washington should have it by now. Something here didn’t add up.

‘Everhardt is a key to the president’s popularity. He’s big, he’s down to earth, he’s popular among men as well as women. It took the party a long time to come up with him as a running mate. Take him away, and the administration is a lot weaker with the voters. He won’t be easy to replace.’

Kraig was silent.

‘And what about the president’s political enemies?’ she asked. ‘What about Colin Goss? How does he feel about this turn of events?’

Kraig shrugged. ‘Am I supposed to have a reaction to that?’ he asked.

She crumpled the wrapper of the granola bar and threw it on the tray.

‘Something isn’t right,’ she said. ‘About Everhardt. And about this.’ She glanced around her at the deserted cafeteria.

Kraig said nothing.

‘I’m going to find out,’ she said. ‘With you or without you. When the time comes, it may be you asking the questions.’

‘Maybe.’ Kraig nodded.

‘I’m betting twelve years of journalism that you won’t like the answers,’ she said.

Picking up her coat, she left the cafeteria. Her shoulders looked very small under her sweater. A tired young woman, no doubt an incurable workaholic, who did not bother to hide her unhappiness.

Kraig liked her. There was a tranquil hopelessness about her that struck a chord in him. She had given up on something a long time ago – love? belonging? – and the emptiness it left behind gave her sharp definition as a person. The reporters he had known were shallow people, slaves to their own ambition. Karen Embry was a human being, albeit a scarred one.

Kraig wondered what she looked like without those clothes on. What her cologne smelled like closer up, when one’s lips were against her skin.

He hoped he would never see her again.

8

Washington

November 22

Susan Campbell was the only child of a wayward New Hampshire beauty queen and a philandering Boston blue blood named Lee Bellinger. Their marriage had lasted seven years. Susan was six when her father abandoned her mother. A series of boyfriends had followed, along with a desperate search for money that led ‘Dede’ Bellinger into brief forays into television, radio, advertising, and public relations, until her taste for alcohol and her notoriously poor driving ability got her killed in a one-car accident on the New Jersey Turnpike.

Susan was brought up by two straitlaced Bellinger aunts who sent her to the best private schools and offered her the combined wisdom of the Bible, the Farmer’s Almanac, and Ralph Waldo Emerson as a guide for living. At fourteen she entered Rosemary Hall as a thoroughly confused young girl with braces, skinny legs, and a worried look.

Four years of private school in the company of privileged girls from the best families in the nation did little for her confidence. She was a shy freshman at Wellesley when a friend introduced her to Michael Campbell, a Harvard junior who was about to undergo a second serious spinal operation after his first one had failed. Michael was frightened; Susan took it upon herself to encourage him. It was in that gesture of giving that she became a woman.

By the time Susan caught her breath Michael had won two Olympic gold medals and was a national celebrity. He finished law school two years after the Olympics, and two years after that ran successfully for the Maryland state legislature. By now Susan was his wife, and she helped him campaign for the US Senate. Her extraordinary blond beauty made her an attractive partner for him on the campaign trail. She had worked her way through college as a catalog model specializing in sportswear and lingerie, and for several years her scantily clad image was on every package of silk panties sold under the exclusive S/Z brand name. That image still haunted her, for the feature articles on her in women’s magazines often included it.

Susan was too beautiful for a political wife, and too shy. Michael’s campaign advisors did not quite know what to do with her.

Then something happened that changed Susan from a minor asset to a crucial weapon in Michael’s political arsenal. She was invited to be a guest on The Oprah Winfrey Show. At Oprah Winfrey’s request Susan brought along the photo album that documented her early years with Michael.

A small comedy of errors took place as Oprah’s camera was zooming in on the photo album.

‘Now, what does this show?’ Oprah was asking.

‘That’s Michael holding the flowers he brought me after our first fight,’ Susan said.

‘Fight?’ Oprah looked at the camera. ‘What were you fighting about?’

‘Sex.’ Susan blurted out the word before she could stop herself.

‘Sex?’ Oprah scented an opportunity.

‘Yes. He thought I was too straitlaced about it.’ Susan stopped in mid-sentence. ‘Uh-oh. I guess I shouldn’t have said that.’

‘Not at all,’ Oprah pursued. ‘Straitlaced in what way?’

‘Making out in public. Things like that,’ Susan said.

‘Oh, you mean you’re more reserved than he is?’ Oprah asked.

‘Yes. I’m rather shy,’ Susan said. ‘It comes from my New England background, I guess.’

‘And Michael isn’t?’ Oprah asked.

Susan laughed. ‘No. Michael isn’t shy.’

‘What sort of venue are we talking about?’ Oprah asked.

‘You mean for making out?’

‘Making out. Yes.’ Oprah glanced at the audience.

‘On the beach in the moonlight,’ Susan said. ‘That sort of thing.’

‘So he likes to take risks,’ Oprah prodded.

‘Risks? Well, he’s very romantic in general, but, yes, I suppose you could say he likes to take risks.’

‘How far do you think he would go?’

‘You mean if he thought no one was watching?’ Susan asked.

‘Mmm – yes,’ Oprah agreed.

‘Oh, the fifty-yard line at the Astrodome, maybe,’ Susan said. Her hand went to her mouth instantly, but it was too late. The audience was in hysterics.

‘Oh, shit,’ Susan said, blushing.

And that was the final note, her embarrassed use of profanity. The audience’s laughter was mingled with applause. Viewers had never seen a politician’s wife speak with such spontaneous candor before.

The clip became famous. Not only did it show off Susan’s unpredictable personality and her charm, but it also referred to her sex life with one of America’s most desirable men, a man whose handsome body was known to women all over the world.

At first Michael’s public relations men were horrified. The sight of Susan on the Oprah show with her profane comment bleeped out seemed a disaster of limitless proportions. But Michael’s tracking polls went up instead of down in the weeks after the broadcast. As for Susan, she was now famous in her own right. She had become a major positive overnight.

At age thirty-two Susan found herself not only the wife of a US senator and the darling of the press, but also a member of a complex and difficult family. Judd Campbell, whose willfulness had done permanent damage to his relationships with Michael’s siblings, loved Susan and had co-opted her as a surrogate daughter. In more ways than one Susan felt exposed and off balance. But she had no choice. She had cast her lot with Michael, and she could not look back.

Susan and Michael had both been busy in recent weeks, too busy to find time for lovemaking. Their first chance came the weekend after the onset of Dan Everhardt’s sudden illness.

They met in the bedroom an hour after dinner. Both were eager. Their clothes came off quickly. Michael gasped when he felt his wife’s naked body against his own.

‘God, I want you,’ he said.

In no time, it seemed, the preliminary caresses were over and he was inside her. His embrace was gentle, though the heat rising in his loins made him groan. Her hands were on his shoulders, her legs wrapped around him.

Susan’s eyes were closed. Michael’s eyes were open. He was looking at her face, whose expression might have denoted pain as much as pleasure. She was very beautiful, he thought. Her breasts, still firm as those of a young girl, pressed against his chest. Her hips moved under him, her sex gripping him in its subtle feminine way, exciting him all the more.

Her hair covered the pillow like a splash of golden liquid. He moved faster. She slipped her hands down his rib cage and held him around his back. Her fingers touched the scar that ran down his spine.

He was very hard inside her, and very long. His strokes became slower, more deliberate. She felt him probing for the core of her, seeking to inflame her. The crisp, earthy smell of him grew more intense. Little moans sounded in her throat.

He kissed her, his tongue slipping into her mouth as his hands pulled her harder onto the straining shaft. She arched her back.

‘Oh, Michael …’

His last thought was for her closed eyes, her fresh young cheeks. She was so beautiful, so innocent …

The paroxysm came so suddenly that he gasped. The flow was long and rhythmic. His loins trembled. His breath came haltingly. It was as though he were drowning.

He stayed inside her for a long time. His pleasure ebbed slowly, and when at last he had returned to himself he kissed her cheeks and her forehead. The complicated eyes were looking at him now, and she was smiling.

She drew him to her breast and held him there. He listened to the beating of her heart.

After a while he ran a finger through her hair.

‘You’re beautiful,’ he said.

She just smiled.

There was a silence. They lay looking at each other.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said.

‘You have nothing to be sorry for,’ he replied.

Another silence.

‘I love you,’ he said.

‘I love you too.’

Susan lay back against the pillow and stared at the ceiling. ‘I’m not myself, Michael.’

He nodded.

‘It’s this awful year,’ she said. ‘With Danny Everhardt sick, and all the things in the media … I’ve lost my balance.’

‘Sure. I understand.’ Michael remained on his side, looking at her. ‘Don’t worry about it.’

‘Thanks.’

There was a silence. Michael was looking at his wife and thinking about the fact that every time they made love there was an excuse.

Susan never had orgasms with him. Not anymore. Probably, he thought, the most important reason was the pressure on them to have children. It had made them both uneasy about their sexuality and even their relationship. Making love had become an endlessly reiterated attempt at something, rather than a simple sharing of affection and pleasure.

It was hard to sort it all out. He loved Susan more than ever. He delighted in everything about her. Her sweetness, her quirky humor, even her fearfulness. He had known before they got married that she was a bit on the neurotic side. He didn’t mind that. It was part of her charm, even if it did make her somewhat more dependent on him.

But as time went on and they became famous, their childlessness had become more and more of an embarrassment. An ambitious political man needed a wife and children. A family.

Consultations with physicians had done nothing to clarify the issue. There was nothing wrong with either of them. Not that medical science could see.

But Michael was aware that the problem had existed even before the issue of childlessness came up. Susan’s ability to experience sexual pleasure in his arms had lessened in direct proportion to the sacrifice of her own independent needs to be his wife, a political wife.

But perhaps it went further back still …

Michael often looked back on those early days, when he was a virtual invalid being nursed by Susan and his sister Ingrid. The intimacy between himself and Susan was born of the long, arduous convalescence from his second spinal operation. When they finally made love, weeks after his body cast was removed, their sex was not only a discovery of each other but a test of his return to health. She had wanted to make him feel strong and competent. They were both nervous that night.

She had been on top. Her bare knees rubbed against his ribs, her hands rested on his chest. As they grew hotter her hair fell over his face and she repeated his name, Michael, Michael, in a voice scalded by sex. The softness of her was amazing. He could feel how deeply she wanted him inside her, possessing her. His orgasm had made him forget all about his back.

Could she have been faking even then? It was possible. After all, she wanted above all to help him, to be useful to him. Perhaps that very loyalty had somehow poisoned her, made it impossible for her to take real sensual pleasure from his body.

There was also her painful childhood. Her father had been an unrepentant philanderer and had abandoned the family. Her mother never really recovered from the loss. Letting herself go sexually with a man might be a difficult issue for Susan.

Nowadays she seemed more tense after making love than before it. Of course she tried to hide it, using tender embraces and affection as her shield. But he knew her too well to be fooled.

Michael let these painful thoughts have their territory in his mind as he cradled Susan’s delicate body in his arms.

‘I spoke to Pam Everhardt,’ she said.

He raised himself on his elbow. ‘How’s she doing?’

‘Terrible,’ Susan said. ‘She can’t believe what’s happened. She’s really beside herself.’

She lay looking at Michael. ‘She depends on Danny for so much. With three children to think about … and they don’t have much money.’

‘They never did,’ Michael said. ‘Danny was never interested. All he ever wanted was a steady salary. He used to joke about it.’

Susan nodded. ‘Pam is frantic. I think she didn’t realize at first how serious it is. Apparently the doctors haven’t given her any news she can hang her hopes on. She’s thinking of getting consultations with some new specialists.’

‘I doubt that that’s necessary,’ Michael said. ‘They’ll throw in everything but the kitchen sink at Walter Reed. Danny is a national figure.’

‘Poor Pam …’

He touched Susan’s shoulder.

‘Uh-oh,’ he said. ‘Are you identifying again?’

‘Afraid so.’

This was an old habit of Susan’s. She always identified strongly with people she knew who suffered misfortunes. When one of Michael’s Maryland constituents made the news on the basis of some horrible tragedy, Susan could be counted on to write the victim personally and often to visit. Her mail was full of heartfelt thanks from people she had touched in this way.

The Everhardts had been entertained in this house many times. Dan and Michael had served on committees together when Dan was a senator, and both were, of course, involved in party strategy meetings. Over the years the two couples had become good friends. Susan looked up to Pam as a sort of older sister. Pam had been in the political wars longer than Susan, though Pam, an overweight, rather homely woman, had never known the burden of visibility the way Susan had.

‘If only they knew what it was,’ Susan said. ‘It’s not knowing that makes it worse.’

Michael nodded. ‘I spoke to her myself today.’

‘Really?’ Susan asked.

‘I’ve been calling her every day, just to see how things are going.’

Susan smiled. This was typical of Michael, this thoughtfulness for a colleague in trouble. A few years ago Dick Friedman, a senator from Colorado who had started the same year as Michael, was injured in a hit-and-run accident that nearly killed him. Michael took personal charge of a bill that Friedman was working on and spent countless hours doing research and making phone calls to potential supporters, without ever asking for thanks or even telling anyone. Michael was loyal – a quality that had made him many friends in Congress.

‘Danny doesn’t even know who Pam is now,’

Susan said. ‘That’s what’s really killing her.’

Michael hugged his wife.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘It’s bad.’

He smiled. ‘Maybe he’ll come out of it just as quickly as he got sick. You’ve heard of people coming out of comas after a long time.’

Susan didn’t answer. She was lying on her side, her face buried against his chest.

‘Michael,’ she said.

‘What?’

She chewed her lip nervously. She was wondering whether to share her fears with him. It might make his own burdens worse.

‘Michael, do you feel safe?’

‘Safe?’ He smiled. ‘Of course I feel safe.’

‘It’s just – everything seems strange,’ she said. ‘Those sick people out in Iowa. And now Dan Everhardt … everything seems so sinister.’

He petted her gently.

‘Bad things happen in the world,’ he said, ‘but that doesn’t mean the sky is falling. Just hang in there, babe. That’s all we can do. Everything will be all right.’

‘Do you think so?’ Susan asked.

‘I know so.’ His smile was confident and even playful, as though he knew a secret and was teasing her with it.

She raised her face to kiss him. She breathed in his warmth. There was a long pause while they lay in silence.

‘Do you forgive me?’ she asked at length.

‘There’s nothing to forgive.’ He kissed her lips. ‘Everything is going to be fine. You’re going to be fine.’

She nodded. ‘Thank you, Michael.’

She didn’t really feel reassured. But she did feel better. Michael always made her feel better.

The phone rang while Michael was in the shower. Naked, Susan darted into the hallway and picked it up.

‘Hello?’

‘Susan.’ The voice was female, low and somewhat husky.

‘Yes?’

‘Susan, I just wanted to let you know something.’

‘Who is this? There must be a mistake …’

‘Susan, Dan Everhardt is not going to get well.’

‘I’m sorry? What did you say?’

‘You heard me. Everhardt will not get well. The president is going to have to appoint a new vice president.’

Susan saw herself in the hall mirror. Her hair was awry, her breasts still moist from her sex with Michael.

‘I really don’t understand … Who is this?’ she asked.

‘Your husband will be the president’s choice, Susan.’

‘My husband? What are you talking about?’

‘I just wanted you to know. We’ll talk again soon.’

‘I – who is this? What are you talking about?’

A low laugh sounded on the line.

‘You’ll understand everything, Susan. In time.’

The caller hung up.

Susan put down the phone. She stood for a moment looking at her naked image in the mirror. She crossed her arms over her breasts as though to hide them. Then she felt a sudden chill, and hurried back to the bed to wait for Michael.

9

Manchester, New Hampshire

November 24

11:30 A.M.

His name was Erroll, like the pianist.

They called him ‘Radio Flyer’ because he was always talking about radio waves. Feeling them, hearing them, even seeing them.

He had been homeless for eleven years now, since they closed the state hospital. He slept in abandoned buildings, ate at shelters, and drank everything from Ripple to lighter fluid.

He carried an old Walkman he had found in the trash years ago. He was rarely seen without the little earphones in his ears. He usually had an intent, busy air about him as he dug into garbage cans, bent to collect scraps of newspaper, or, quite often, stood outside appliance stores staring at news broadcasts on display TV sets.

There were those who wondered if there was any sound coming through his famous earphones. ‘He doesn’t need sound,’ said some. ‘He’s got plenty of voices in his head.’

Today, though, the twenty-four-hour all-news station was actually penetrating to Erroll’s brain, for he had put new batteries into the Walkman two weeks ago and they were still running. He nodded knowingly as he listened to the news.

The two beat cops in their cruiser smelled him almost before they saw him. He had an unforgettable odor of stale sweat, urine, alcohol, and tooth decay. They were never glad to see him, for he was full of garbled stories of aliens who were bombarding him with waves.

‘They weren’t supposed to radiate me,’ he would say, ‘but there was a mix-up. They got the wrong guy. Now these rays are killing me, and I can’t get them to stop.’

Usually the cops took him to a shelter whose personnel then escorted him to a clinic where he got medication. But more often than not he didn’t take the medication. He said it made him drool.

Today he shambled toward the cruiser with a bit more purpose than usual. As he approached the car he took off his earphones.

‘Morning, Erroll,’ said the driver. ‘What’s on your mind?’

‘I found a dead body,’ he said.

‘You found a body?’ the driver asked.

‘A dead person,’ he said. ‘Smells, too. Maybe a few days. Wait till you see the hands and feet.’

‘Hands and feet? What are you talking about, Erroll?’

The bum was visibly excited.

‘I keep telling you guys. The men upstairs are making changes. I’m not the only one. Wait till you see the hands and feet.’

‘Where is it, Erroll?’

‘In a Dumpster in the alley off Chestnut Street. Been there all morning.’

The two cops looked at each other. They had long since learned not to attribute any truth to Erroll’s pronouncements. But a body in a Dumpster was something that had to be checked out.