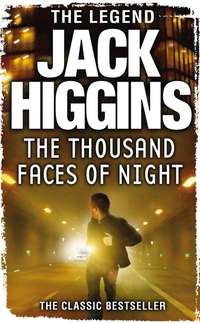

The Thousand Faces of Night

Faulkner’s eyes started from his head as he began to choke, and then Marlowe was aware of a movement to his left. He released Faulkner and turned as Harris cut viciously at his face with the knife. He warded off the blow with his right arm and was conscious of pain as the knife ripped his sleeve. He caught the small man by his left wrist and with a sudden pull, jerked him across the room to crash against the wall.

As he turned, Butcher struck at him with a heavy rubber cosh, the blow catching him across the left shoulder and almost paralysing his arm. He chopped Butcher across the right forearm with the edge of his hand and the big man cried out in pain and dropped the cosh. Marlowe turned towards the door and Faulkner pushed out a foot and tripped him so that he fell heavily to the floor. Butcher moved in quickly, kicking at his ribs and face. Marlowe rolled away, avoiding most of the blows and scrambled up. Harris was back on his feet, shaking his head in a dazed fashion. He stumbled across the room and stood beside Butcher. For a moment there was a brief pause as the four men stood looking at each other and then Faulkner pulled an automatic out of his inside breast pocket.

Marlowe moved backwards until he faced them from the other side of the bed, the open window behind him. Faulkner appeared to be having difficulty with his voice. He choked several times before he managed to say, ‘I’ll take that key, Hugh, and you’ll tell me where the money is. I don’t want to use this, but I will if I have to.’

‘I’ll see you in hell first,’ Marlowe said.

Faulkner shrugged and covered him carefully with the automatic. ‘Go and get the key,’ he told Butcher.

The big man started forward. Marlowe waited until he was almost on him and then he grabbed the wooden chair and tossed it straight at Faulkner. In the same moment he turned and vaulted through the open window.

He landed knee-deep in the pile of coke and lost his balance, rolling over and sliding to the bottom. He got to his feet and looked up. Butcher and Faulkner were at the window. For a moment they stared down at him and then they were pulled aside and Harris scrambled on to the windowsill. As he jumped, Marlowe turned and ran across the tracks towards some railway coaches which were standing in a nearby siding.

The fog was thickening rapidly now and visibility was poor. He stumbled across the tracks into the shelter of the coaches and paused for a moment to look back. Harris was running well and the blade of his knife gleamed dully in the rain. Marlowe started to run again. There was a terrible pain in his side where Butcher had kicked him and blood was dripping from his left arm.

As he emerged from the shelter of the coaches he saw a goods train moving slowly along a nearby track, gathering speed as it went. He lurched towards it and ran alongside, pulling at one of the sliding doors until it opened. He grabbed at the iron rail and hauled himself up.

As he leaned against the door Harris appeared, running strongly, his face white with effort. As he grabbed for the handrail, Marlowe summoned up his last reserve of strength and kicked him in the chest with all his force. The small man disappeared and then the train moved forward rapidly, clattering over the points as it travelled away from London towards the North.

For a moment longer Marlowe leaned in the opening and then he pushed the sliding door shut and slid gently down on to the straw-littered floor.

2

He lay face downwards in the straw for a long time, chest heaving as his tortured lungs fought for air. After a while he pushed himself up and sat with his back against a packing case.

The wagon was old and battered with many gaps in its slatted sides through which the light filtered. Gradually his breathing became easier and he stood up and removed his raincoat and jacket. The slash in his arm was less serious than he had imagined. A superficial cut, three or four inches long, where the tip of the knife had sliced through his sleeve. He took out his handkerchief and tied it around the wound, knotting it with his teeth.

He shivered and pulled on his jacket as wind whistled between the slats carrying a faint spray of cold rain. As he buttoned his raincoat he examined the packing cases that stood about him and was amused to find they were addressed to a firm in Birmingham. So the wheel had come full circle? He had escaped from Birmingham in a goods train five years before. Now he was on his way back again. Masters would have been amused.

He sat down with his back against a packing case by the door and wondered what Masters was doing now. Probably making sure that every copper in London had his description. Faulkner would be doing exactly the same thing, in his own way. Marlowe frowned and fumbled for a cigarette. London was out of the question for the moment. With every crook in town on the watch for him, he wouldn’t last half an hour.

He thrust his hands deep into his pockets and considered the position. Perhaps things had worked out the best after all. A week or two in the Midlands or the North to let things cool off and then he could return quietly and collect what he had left in the safe deposit of the firm near Bond Street.

His fingers fastened over the key in his jacket pocket and he took it out and examined it. Twenty thousand pounds. He smiled suddenly. He had waited for five years. He could afford to wait for another week or two. He replaced the key in his pocket, pulled his cap down over his eyes, and went to sleep.

He came awake slowly and lay in the straw for a moment trying to decide where he was. After a while he remembered and struggled to his feet. He was cold and there was a dull, aching pain in his side where Butcher had kicked him. The train was moving fast, rocking slightly on the curves, and when he pulled the door open a gust of wind dashed violently into his face.

A curtain of fog shrouded the fields, cutting visibility down to thirty or forty yards. The cold air made him feel better and he sat down again, leaving the door open, and considered his next move.

Birmingham was out. There was always the chance that Faulkner might have discovered the train’s destination. There could easily be a reception committee waiting. Faulkner had friends everywhere. It would be best to leave the train at some small town farther along the line. The sort of place that had a name no one had ever heard of.

He emptied his pockets and checked on his available assets. There was an insurance card, his driving licence which he had renewed each year he had been in prison, and fifteen shillings in silver. He still had ten cigarettes left in the packet he had bought in the snack bar. He smiled ruefully and decided it was a good job he had the licence. With luck he might be able to get some sort of a driving job. Something that would keep him going until he was ready to return to London.

The train began to slow down and he got up quickly and closed the door leaving a narrow gap through which he could stare out into the fog. A signal box loomed out of the gloom and a moment later, the train moved past a small station platform. Marlowe just had time to make out the name Litton before the station was swallowed up by the fog.

He shrugged and a half-smile appeared on his face. This place sounded as good as any. He pushed open the door and as the train slowed even more, he dropped down into the ditch at the side of the track. Before him there was a thorn hedge. He moved along it for a few yards until he found a suitable gap through which he forced his way into a quiet road beyond. The rain was hammering down through the fog unmercifully and he pulled up his coat collar and began to walk briskly along the road.

When he came to the station he paused and examined the railway map that hung on the wall in a glass case. He had little difficulty in finding Litton. It was on the main line, about eighty miles from Birmingham. The nearest place of any size was a town called Barford, twelve or fifteen miles away.

The hands of the clock above the station entrance pointed to three and he frowned and started down the hill towards the village, dimly seen through the fog. He had obviously slept on the train for longer than he had imagined.

The main street seemed to be deserted and the fog was much thicker than it had been on the hill. He saw no one as he walked along the wet pavement. When he paused for a moment outside a draper’s shop his reflection stared out at him from a mirror in the back of the window. With his cap pulled down over his eyes and his great shoulders straining out of the sodden raincoat, he presented a formidable and menacing figure.

He lifted his left hand to wipe away the rain from his face and cursed softly. Blood was trickling down his arm, soaking the sleeve of his raincoat. He thrust his hand deep into his pocket and hurried on. He had to find somewhere quiet where he could fix that slash before he ran into anyone.

The street seemed to be endless. He had been walking for a good ten minutes before he came to a low stone wall topped by spiked railings. A little farther along there was an open iron gate and a sign which read Church of the Immaculate Heart, with the times of Mass and Confession in faded gold letters beneath it.

He walked along the flagged path and mounted the four or five steps that led to the porch. For a moment he hesitated and then he pulled off his cap and went inside.

It was warm in there and very quiet. For a little while he stood listening intently and then he slumped down in a pew at the back of the church. He looked down towards the winking candles and the altar and suddenly it seemed to grow darker and he leaned forward and rested his head against a stone pillar. He was more tired than he had been in a long time.

After a while he felt better and stood up to remove his raincoat and jacket. The handkerchief had slipped down his arm exposing the wound and blood oozed sluggishly through the torn sleeve of his shirt. As he started to fumble with the knotted handkerchief there was a slight movement at his side. A voice said quietly, ‘Are you all right? Can I help you?’

He swung round with a stifled exclamation. A young woman was standing beside him. She was wearing a man’s raincoat that was too big for her and a scarf covered her head. ‘How the hell did you get there?’ Marlowe demanded.

She smiled slightly and sat down beside him. ‘I was sitting in the corner. You didn’t notice me.’

‘I didn’t think anyone would be in church in the middle of the afternoon,’ he said. ‘I came in out of the rain to fix my arm. The bandage has slipped.’

She lifted his arm and said calmly, ‘That looks pretty nasty. You need a doctor.’

He jerked away from her and started to untie the handkerchief with his right hand. ‘It’s only a bad cut,’ he said. ‘Doesn’t even need stitching.’

She reached over and gently unfastened the knot. She folded the handkerchief into a strip and bound it tightly about the wound. As she tied it she said, ‘This won’t last for long. You need a proper bandage.’

‘It’ll be all right,’ Marlowe said. He stood up and pulled on his coat. He wanted to get away before she started asking too many questions.

As he belted his raincoat she said, ‘How did you do it?’

He shrugged. ‘I’ve been hitch-hiking from London. Going to Birmingham to look for work. I ripped myself open on a steel spike when I was climbing down from a lorry.’

He started to walk away and she followed at his heels. At the door, she kneeled and crossed herself and then she followed him out into the porch.

‘Well, I’d better be off,’ Marlowe said.

She looked out into the driving rain and the fog and said, with a slight smile, ‘You won’t stand much chance of a lift in this.’

He nodded and said smoothly, ‘If I can’t, I’ll catch a bus to Barford. I’ll be all right.’

‘But there isn’t a bus until five,’ she said. ‘It’s a limited service on this road.’ She appeared to hesitate and then went on, ‘You can come home with me if you like. I’ll bandage that cut for you properly. You’ve plenty of time to spare before the bus goes.’

Marlowe shook his head and moved towards the top step. ‘I wouldn’t dream of it.’

Her mouth trembled and there was suppressed laughter in her voice as she replied, ‘My father should be home by now. It will be all quite proper.’

An involuntary smile came to Marlowe’s face and he turned towards her. For the first time he realized that she had a slight foreign intonation to her speech and an oddly old-fashioned turn of phrase. Suddenly and for some completely inexplicable reason, he felt completely at home with her. He grinned and took out his cigarettes. ‘You’re not English, are you?’

She smiled back at him, at the same time refusing a cigarette with a slight gesture of one hand. ‘No, Portuguese. How did you know? I rather prided myself on my accent.’

He hastened to reassure her. ‘It isn’t so much your accent. For one thing, you don’t look English.’

Her smile widened. ‘I don’t know how you intended that, but I shall take it as a compliment. My name is Maria Magellan.’

She held out her hand. He hesitated for a moment and then took it in his. ‘Hugh Marlowe.’

‘So! Now we know each other and it is all very respectable,’ she said briskly. ‘Shall we go?’

He paused for only a moment before following her down the steps. As she passed through the gate in front of him he noticed that she was small, with the ripe figure peculiar to southern women and hips that were too large by English standards.

They walked along the pavement, side by side, and he glanced covertly at her. Her face was smoothly rounded with a flawless cream complexion. The eyebrows and the hair that escaped from under the scarf were coal black and her red lips had an extra fullness that suggested sensuality.

She turned her head unexpectedly at one point and caught him looking at her. She smiled. ‘You’re a pretty big man, Mr Marlowe. How tall are you?’

Marlowe shrugged. ‘I’m not sure. Around six-three, I think.’

She nodded, her eyes travelling over his massive frame. ‘What kind of work are you looking for?’

He shrugged. ‘Anything I can get, but driving is what I do best.’

There was a gleam of interest in her eyes. ‘What kind of driving?’

‘Any kind,’ he said. ‘Anything on wheels. I’ve driven the lot, from light vans to tank-transporters.’

‘So! You were in the Army?’ she said and her interest seemed to become even more pronounced.

Marlowe flicked his cigarette into the rain-filled gutter. ‘Yes, I think you could say I was in the Army,’ he said and there was a deadness in his voice.

She seemed to sense the change of mood and lapsed into silence. Marlowe walked moodily along beside her trying to think of something to say, but it was not necessary. They turned into a narrow lane and came to a five-barred gate which was standing open. She paused and said, ‘Here we are.’

A gravel drive disappeared into the fog in front of them and Marlowe could make out the dim shape of a house. ‘It looks like a pretty big place,’ he said.

She nodded. ‘It used to be a farmhouse. Now there’s just a few acres of land. We run it as a market garden and fruit farm.’

He looked up into the rain. ‘This kind of weather won’t be doing you much good.’

She laughed. ‘We haven’t done too badly. We got nearly all the apples in last week and most of our other produce is under glass.’

A gust of wind lifted across the farmyard, rolling the fog in front of it, and exposed the house. It was an old, grey stone building, firmly rooted into the ground and weathered by the years. On one side of the yard there were several outbuildings and on the other, a large, red-roofed barn.

The front door was protected by an old-fashioned glass porch and outside it a small yellow van was parked. inter-allied trading corporation – barford, was printed on its side in neat black letters. Maria Magellan paused abruptly and there was something like fear on her face. She darted forward and entered the house.

Marlowe followed more slowly. He ducked slightly under the low lintel of the door and found himself in a wide, stone-flagged hall. The girl was standing outside a door on the left through which angry voices could be heard. She flung the door open and entered the room and Marlowe waited in the hall, hands thrust deep into his pockets, and watched.

Inside the room two men faced each other across a table. One of them was old with grizzled hair and a white moustache that stood out clearly against swarthy skin that was the colour of tanned leather.

The other was a much younger man, powerfully built with good shoulders. His face was twisted menacingly as he said, ‘Listen you old fool. Either you come in with us or you go out of business. That’s Mr O’Connor’s last word.’

The old man’s eyes darted fire and he slammed a hand hard against the table. His English was good but with a heavy accent and his voice was trembling with rage. ‘Listen, Kennedy. You tell O’Connor this from me. Before he puts me out of business I put a knife into him. On my life I promise it.’

Kennedy laughed contemptuously. ‘You bloody old fool,’ he said. ‘Mr O’Connor can stamp you into the dirt any time he wants. You’re small stuff, Magellan.’

The old man gave a roar of anger and moved fast around the table. He swung hard with his right fist, but the years were against him. Kennedy blocked the punch with ease. He grabbed the old man by the shirt and started to beat him across the face with the flat of his hand. The girl screamed and ran forward, tearing at Kennedy with her fingers. He pushed her away with such force that she staggered across the room and lost her balance.

A cold rage flared in Marlowe and he moved forward into the room. Kennedy raised his hand to strike the old man again and Marlowe grabbed him by the shoulder and swung him round so that they faced each other. ‘How about trying me?’ he said. ‘I’m a bit nearer your size.’

Kennedy opened his mouth to speak and Marlowe smashed a fist into it. The tremendous force of the blow hurled Kennedy across the table. He gave a terrible groan and pulled himself up from the floor. Marlowe moved quickly around the table and grabbed him by the front of his jacket. ‘You bastard!’ he said. ‘You dirty, lousy bastard.’

And then a mist came before his eyes and it wasn’t Kennedy’s face that he saw before him. It was another face. One that he hated with all his being and he began to beat Kennedy methodically, backwards and forwards across the face, with his right hand.

The girl screamed again, high and clear, ‘No, Marlowe! No – you’ll kill him!’

She was tugging at his arm, pleading frantically with him, and Marlowe stopped. He stood for a moment staring stupidly at Kennedy, fist raised, and then he gently pushed him back against the table.

He was trembling slightly and there was still that slight haze before his eyes, almost as if some of the fog had got into the room. He clenched his fists to try and steady the trembling and noticed that blood was trickling down his left sleeve again.

The girl released her hold on him. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I had to stop you. You would have killed him.’

Marlowe nodded slowly and passed a hand across his face. ‘You did right. Sometimes I don’t know when to stop and this rat isn’t worth hanging for.’

He moved suddenly and grabbing Kennedy by the collar, propelled him roughly out of the room and into the hall. He pushed him through the porch and flung him against the van. ‘If you’ve got any sense you’ll get out of here while you’ve got a whole skin,’ he said. ‘I’ll give you just five minutes to gather your wits.’

Kennedy was already fumbling for the handle of the van door as Marlowe turned and went back into the house.

3

When he went into the room there was no sign of Maria, but her father was busy at the sideboard with a bottle and a couple of glasses. His face split into a wide grin and he walked quickly across and handed Marlowe a glass. ‘Brandy – the best in the house. I feel like a young man again.’

Marlowe swallowed the brandy gratefully and nodded towards the window as the engine of the van roared into life. ‘That’s the last you’ll see of him.’

The old man shrugged and an ugly look came into his eyes. ‘Who knows? Next time I’ll be prepared. I’ll stick a knife into his belly and argue afterwards.’

Maria came into the room, a basin of hot water in one hand and bandages and a towel in the other. She still looked white and shaken, but she managed a smile as she set the bowl down on the table. ‘I’ll have a look at that arm now,’ she said.

Marlowe removed his raincoat and jacket and she gently sponged away congealed blood and pursed her lips. ‘It doesn’t look too good.’ She shook her head and turned to her father. ‘What do you think, Papa?’

Papa Magellan looked carefully at the wound and a sudden light flickered in his eyes. ‘Pretty nasty. How did you say you got it, boy?’

Marlowe shrugged. ‘Ripped it on a spike getting off a truck. I’ve been hitching my way from London.’

The old man nodded. ‘A spike, eh?’ A light smile touched his mouth. ‘I don’t think we need bother the doctor, Maria. Clean it up and bandage it well. It’ll be fine inside a week.’

Maria still looked dubious and Marlowe said, ‘He’s right. You women make a fuss about every little scratch.’ He laughed and fished for a cigarette with his right hand. ‘I walked a hundred and fifty miles in Korea with a bullet in my thigh. I had to. There was no one available to take it out.’

She scowled and quick fury danced in her eyes. ‘All right. We don’t get the doctor. Have it your own way. I hope your arm poisons and falls off.’

He chuckled and she bent her head and went to work. Papa Magellan said, ‘You were in Korea?’ Marlowe nodded and the old man went over to the sideboard and came back with a framed photo. ‘My son, Pedro,’ he said.

The boy smiled stiffly out of the photo, proud and self-conscious of the new uniform. It was the sort of picture every recruit has taken during his first few weeks of basic training. ‘He looks like a good boy,’ Marlowe remarked in a non-committal voice.

Papa Magellan nodded vigorously. ‘He was a fine boy. He was going to go to Agricultural College. Always wanted to be a farmer.’ The old man sighed heavily. ‘He was killed in a patrol action near the Imjin River in 1953.’

Marlowe examined the photo again and wondered if Pedro Magellan had been smiling like that when the bullets smashed into him. But it was no use thinking about that because men in war died in so many different ways. Sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly, but always scared, with fear biting into their faces.

He grunted and handed back the photograph. ‘That was a little after my time. I was captured in the early days when the Chinese took a hand.’

Maria looked up quickly. ‘How long were you a prisoner?’

‘About three years,’ Marlowe told her.

The old man whistled softly. ‘Holy Mother, that’s a long time. You must have had it rough. I hear those Chinese camps were pretty tough.’

Marlowe shrugged. ‘I wouldn’t know. I wasn’t in a camp. They put me to work in a coal mine in Manchuria.’

Magellan’s eyes narrowed and all humour left his face. ‘I’ve heard a little about those places also.’ There was a short silence and then he grinned and clapped Marlowe on the shoulder. ‘Still, all this is in the past. Maybe it’s a good thing for a man, like going through fire. A sort of purification.’

Marlowe laughed harshly. ‘That sort of purification I can do without.’

As Maria pressed plaster over the loose ends of the bandage she said quietly, ‘Papa has had a little of that kind of fire in his time. He was in the International Brigade in Spain. The Fascists held him in prison for two years.’

The old man shrugged expressively and raised a hand in protest. ‘Why speak of these things? They are dead. Ancient history. We are living in the present. Life is often unpleasant and always unfair. A wise man puts it all down to experience and does the best he can.’