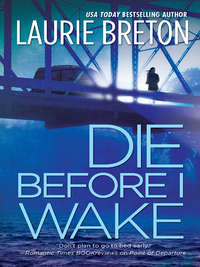

Die Before I Wake

“I’ll give you a list. Girls, pick up your crayons and coloring books and take them upstairs. And put them away. I don’t want to come home and find them strewn around your room.”

“It’s not fair,” Taylor said. “I want a doughnut!”

“Yeah,” Sadie said, taking a cue from her older sister. Tiny fists planted on her hips, she echoed, “It’s not fair!”

“Life isn’t fair,” my mother-in-law snapped, “and you shouldn’t expect it to be. The sooner you learn that, the better off you’ll be.”

Yikes. Glad I wasn’t on the receiving end of her cutting comment, I carefully arranged my face in the most neutral expression I could manage. The girls made a few more token protests, but it was obvious that in this house, Grandma ruled. So while Jeannette wrote out a list for me, the girls put away their toys.

Afterward, I got them settled in the backseat of the Land Rover and, as I drove away from the house, I marveled at my amazing transformation from big-city career woman to small-town mom, complete with husband, two kids, and an SUV. I felt a little like Barbie, after she and Ken had built their Dream House somewhere in American suburbia. The only thing needed to complete the picture was a large, hairy dog.

I slowed for a red light. It turned green before I reached it. I stepped on the gas, and forgot to shift gears. The car stalled halfway through the intersection. Muttering under my breath, I pumped the accelerator, popped the clutch, and took off, tires squealing on the pavement.

From the backseat, Taylor said, in a tone that was far too accusatory for a seven-year-old, “Why are you having so much trouble driving?”

I glanced in the rearview mirror. Her eyes were narrowed with suspicion. Whatever happened to children being seen but not heard? “I’m not having trouble,” I said through gritted teeth. “I’m just a little rusty.”

“My mom never had trouble driving it.”

I checked the mirror again. This time, my stepdaughter looked smug, and far older than her seven years. Why was it that she always made me feel as though she were the adult and I the child? I took a breath and forced myself to be civil. “This was your mom’s car?”

A smile flitted over her face. The little wretch had hit a nerve, and she knew it. “Yes,” she said. “And Mom was a good driver. Sadie never got carsick when she rode with Mom.”

Mild panic assailed me as I imagined myself cleaning vomit from the backseat of a very expensive Land Rover. “Sadie?” I said in alarm. “Are you carsick?”

“I’m not sick,” Sadie piped up. “I love to ride.”

In the mirror, Taylor was grinning. Gotcha! her face seemed to say.

I reminded myself again that I was the adult, and far too mature for the kind of retaliation I was contemplating. I had other, more important things to focus on. Like the fact that the car I was driving belonged to a dead woman. A dead woman who happened to be my predecessor. Thanks, Tom. It would’ve been really nice if he’d bothered to drop a hint.

I wasn’t sure why it gave me the willies. Did I think Beth’s spirit was still hovering around, clucking in disapproval as I stole her husband, laid claim to her children, and burned out her clutch? It wasn’t as though she’d died in the vehicle and was therefore doomed to haunt it for all of eternity. Although, come to think of it, I was sure Tom had told me his wife died in an accident. If that was true, and if this vehicle really had belonged to her, then what had she been driving?

Maybe she hadn’t been driving at all. Maybe she’d been a passenger in somebody else’s car. Tom hadn’t gone into any detail about her death. I could tell it bothered him to talk about it; the wound was still a little too fresh to start picking at the scab, so I hadn’t pried. But I had to admit I was curious.

I glanced in the mirror again. Sadie was staring out the window, humming under her breath, some tuneless little ditty that kept repeating itself, over and over. Or maybe that was just Sadie’s interpretation of how the song went. Taylor had tired of toying with me and was now focused on her Game Boy. The self-satisfied look on her face confirmed what I already knew: She was going to be a challenge. But one way or another, I’d win the war. After all, I’d once been a seven-year-old know-it-all. To paraphrase an old country song, I’d forgotten more than she would ever know about being a brat. The kid didn’t stand a chance against me.

I eventually found the grocery store—the town was too small for it to stay hidden for long—and I pulled into a parking space. Just to satisfy my curiosity, I opened the glove compartment and rummaged around until I found the auto registration. I told myself I wasn’t snooping. After all, the vehicle belonged to Tom and, as his wife, that meant it was half mine. Besides, if I got pulled over for some infraction, I’d need to know where the registration was. I had a right to snoop.

I could rationalize until the cows came home, but in the end, it didn’t matter. The registration didn’t answer any of my questions, because the car was registered to Tom. It might have been Beth’s vehicle, as Taylor had said, or my stepdaughter might have been needling me. It was impossible to tell. The only way I’d know would be to ask Tom.

I shoved the registration back into the glove compartment and slammed it shut. “Okay, girls,” I said briskly. “Let’s do this!”

For a weekday afternoon, the store was busy. Lots of harried housewives and elderly people pushing their shopping carts up and down the aisles. Zippy muzak, designed to move shoppers along at the optimum pace for picking and choosing, blared out of overhead speakers. I checked Jeannette’s list. It was extensive, but not detailed. Standing in front of the milk case, I pondered all the choices, wondering what brand my mother-in-law usually bought. Did I dare to ask Taylor? If I did ask, could I trust her answer? Would she tell me the truth, or try to sabotage my already shaky relationship with Tom’s mother by pointing me in the wrong direction?

I wouldn’t put it past her. The kid was sly, and I’d once walked in her shoes. I could remember a time or two when I’d done just about anything I could to get rid of my father’s latest girlfriend. I hadn’t cared how obnoxious I was, hadn’t cared how childish some of my stunts were or how much trouble I might get into afterward. All that mattered was the end result: one more irritating woman out of our lives. One more opportunity for our nuclear family—that would be Dave and me—to remain intact. I’d been a real piece of work. And Taylor was so much like me it was scary.

From her perch high in the cart, Sadie kicked her legs and said, “Can I have orange juice?”

Orange juice hadn’t been on Jeannette’s list. I weighed the relative merits of garnering brownie points with Sadie against the pain of being reprimanded by my mother-in-law for the second time today, and decided to make the ultimate sacrifice. After all, I’m one tough chica. Just ask my friend Carmen. She’s told me that so often, I’ve started to believe her. I knew I could stand up to Jeannette Larkin and whatever she dished out. This was a simple matter of survival. “You tell me what kind of milk Grandma buys,” I told Sadie, “and I’ll let you have orange juice.”

Without hesitation, she pointed. “That one.”

My bribery skills were being honed to a fine edge. I opened the cooler door and took out the milk, grabbed two miniature bottles of OJ, and consulted my list. Next item: cat food. As descriptions go, it was beyond vague. There were eight trillion brands of cat food on the shelves, enough to take up one entire side of the pet food aisle. Was I supposed to guess? Did she want dry food or canned? Enough for one cat, or several? Were we talking kitten chow, or something specially designed for geriatric felines? I was clueless, especially considering that in the twenty-four hours since I arrived at Casa Larkin, I hadn’t seen any evidence that a cat actually lived there.

I was about to ask Sadie for clarification when I looked around and realized Taylor was nowhere to be seen. “Sadie?” I said, mildly alarmed. “Where’s your sister?”

She shrugged with childlike unconcern. “I don’t know.”

Great. This was all I needed. Tom’s mother already hated me. I couldn’t wait to hear what she’d say if I lost her grandchild.

With my heart thudding and visions of an Amber Alert dancing through my brain, I wheeled the cart around the corner of the next aisle. There, at the far end, was my missing stepdaughter, deep in conversation with some blonde who looked more like Julia Roberts than Julia Roberts.

I mentally cancelled the Amber Alert. Taylor and I were going to sit down later this afternoon and have a long talk about sticking together in public places. Pedophiles and serial killers lurked around every corner, even in small towns like this one. “Who’s that lady your sister’s talking to?” I asked Sadie.

Her head swiveled around. “Auntie Mel!” she shrieked so loudly they probably heard her in the next county. I struggled to regain my hearing, relieved to know that Taylor hadn’t been about to waltz out of the store hand in hand with some fabulous-looking stranger. Before I could stop her, Sadie had scrambled out of the cart and down to the floor. I stood glued to the spot as she ran the length of the aisle and wrapped herself ecstatically around the woman’s legs.

“Hey, yourself,” almost-Julia said, sticking a roll of price tags into the pocket of her teal-colored smock with the red-and-white Shop City logo stitched just above the breast. She gave me a long, assessing glance, then turned her attention back to Sadie and said, “How are you, baby doll?”

“I’m wonderful! When are you coming to visit?”

“I don’t know, hon. I’m pretty busy. But I’ll call your Gram one of these days soon and we’ll make plans.”

I maneuvered my cart to a stop. “Hi,” I said. “I’m Julie Larkin.”

The look she gave me was glacial. Crouching down, she hugged both girls and said, “Why don’t you girls run over to the bakery and see what Yvette has for you? I’m pretty sure she just baked a new batch of chocolate-chip cookies. Tell her I sent you.”

The girls hugged her and disappeared, their homing instinct infallible when it came to cookies. I propped a foot on the undercarriage of my shopping cart and said, “Tom doesn’t allow the girls to eat sugar.”

Almost-Julia stood up to her full five-foot-zero. “Yes,” she said, her expression challenging me to do something about it. “I know.”

Ah. A fellow subversive. We had something in common. “And who are you?” I asked, since she’d failed to provide me with a name, rank, or serial number.

“Melanie Ambrose. My sister used to be married to your husband. Before he killed her.”

“Come again?”

“You heard me. Tom Larkin murdered my sister.”

She was obviously deranged. While I gaped at her, an elderly man who smelled of sweat and pipe tobacco took an inordinate amount of time picking out a box of breakfast cereal. When he’d finally moved on, I said, “I don’t understand what you mean. Beth died in an accident.”

Melanie cocked her head to one side and looked at me with a sad, knowing smile. “Really? So that’s what he told you?”

“Well, I, uh—” I struggled to remember whether he’d used those exact words or whether I’d simply inferred them. For the first time, I wasn’t sure. “I think.”

“That lying sack of shit. Beth didn’t die in any accident. That’s just his guilt talking. He doesn’t have the cojones to speak the truth.”

My fingers tightened on the handle of the shopping cart. “Oh? And just what is the truth?”

“You want to know the truth? I’ll tell you.” Her pretty face twisted into a skeletal grimace of a smile. “Congratulations on your marriage. I hope you survive it.”

Four

I slid the meat loaf into the oven and set the timer. The girls, still on a sugar high, were in the living room watching SpongeBob SquarePants. I turned on the burner under the potatoes, opened the bakery box, and took out a jelly doughnut. If I kept this up, pretty soon the box would be empty. Nibbling, I mentally wandered back to what Melanie Ambrose had told me. Two years ago, on a lovely moonlit summer night, Beth Larkin had driven her Land Rover—the same Land Rover I was now driving—up onto the Swift River Bridge, where she’d proceeded to remove her shoes and her glasses, leaving them on the front seat to weigh down the suicide note she’d written before she left the house. Then she’d climbed barefoot and half-blind onto the bridge railing, leaned forward, and taken a header off the side.

Jesus Christ. How was I supposed to respond to that?

Like a mother grizzly with her cub, I’d steadfastly defended my husband. In part because he’s the love of my life, and in part because I firmly believe that each of us is responsible for our own happiness, or lack thereof, and have no right to blame our failings on other people. Anybody who chooses to deal with their problems by jumping off a bridge surely has mental health issues that are not the result of anything another person may have done—or not done—to them. After mounting a defense of Tom so brilliant it would have made F. Lee Bailey proud, I grilled Melanie for more details. Of course, she couldn’t pinpoint a single concrete reason that would have led Beth’s unhappiness back to Tom. No, she admitted, he wasn’t an alcoholic or a drug addict. No, he didn’t beat his wife. Nor, as far as Mel knew, did he run around behind her sister’s back. All she really had to go on—and it was pretty damn flimsy evidence—was that her sister had been deliriously happy for the first few years of her marriage to Tom. Then, as time wore on, Beth’s demeanor changed. She became withdrawn and distant. She started keeping secrets. She stopped participating in life, became more of an observer, wearing her unhappiness around her like a heavy, black cloak.

And, of course, somehow this was Tom’s fault.

This sounded to me like classic symptoms of clinical depression, but there was no point in suggesting to Mel that her sister suffered from mental illness. It would only exacerbate her already considerable pain, and she wouldn’t believe me anyway. Her sister was dead, and she needed somebody to blame it on. As Beth’s husband, Tom was the nearest and most likely target. And as Tom’s new wife, I was firmly rooted in the enemy camp.

So I let it go. But it gnawed at me, this newly gained knowledge that not only had Tom’s first wife chosen to take her own life, but that he’d lied to me about it. Or, at the very least, if he hadn’t lied, he hadn’t been fully forthcoming. It bothered me. It bothered me a lot. I’m a very open person. I say what I think and I think what I say. My candor is legendary among my friends and acquaintances. I don’t hide things from the people I care about; my life is the proverbial open book. Tom’s, it seemed, wasn’t. As much as I hate seeing people toss around psychobabble buzzwords like so much confetti, I had to admit that I was seeing a significant amount of dysfunction in this family. And if there was one thing I was familiar with, it was family dysfunction.

Tom and his mother arrived home at the same time, with Riley, who might not sleep here but appeared to eat all his meals here, straggling in a couple of minutes later. I already had the dining room table set, the girls washed up and their hair combed, and was just finishing dinner preparations when the rest of the family came in. Jeannette checked to make sure I had everything under control, then disappeared upstairs, presumably to remove the odor of wet doggie from her person. Riley headed to the sink to wash his hands. Tom came directly to where I stood at the stove, checking the potatoes for done-ness.

He planted a kiss on the back of my neck and murmured in my ear, too low for anybody else to hear, “I missed you today.”

Turning around, I wrapped my arms around him. He pressed me back against the oven door and kissed me the way a woman wants to be kissed by the man she loves. I drew in the warm scent of him, leaned into his body and kissed him back.

“Christ on a crutch,” Riley said from across the kitchen. “Why don’t you two just get a room?”

Tom drew back and gave me a wink. “We already have one upstairs.”

“Then go up there if you have to play kissy-face. Although you two might be wildly enthusiastic about your sex life, the rest of us have appetites we don’t want ruined.”

“Jealousy,” Tom told his brother. “It so doesn’t become you.”

Rolling his eyes, Riley wandered off to somewhere, leaving us alone in the kitchen. “Tom,” I said, “we have to talk.”

The now-familiar furrow between his eyebrows—the one I’d never seen until we arrived in Newmarket—put in an appearance. “If it’s a problem with my mother—”

“It’s not about your mother. It’s something else. But it can wait until after we eat.”

“Should I be worried?”

“As in am I about to pack my bags and run back to L.A.?”

“As in precisely that.”

I rested a hand against his abdomen, felt it rise and fall with his breathing. “Stop worrying,” I said. “There’s not a snowball’s chance in hell of me leaving you.”

“Hold that thought,” he said as the girls bounced into the kitchen. “We’ll discuss it in more detail later.”

Supper was over, the table cleared, the dishes washed, the girls read to and tucked into their beds. Tom and I were finally alone. Perched cross-legged on our bed, my hands clasped around my ankles, I watched my husband’s mirrored reflection through the open bathroom door as he peeled off his dress shirt and dropped it into the hamper. His body was lean and sinewy, with nice shoulders, well-defined muscles and a narrow line of dark hair that ran from breastbone to navel. My breath quickened at the sight of all that male pulchritude. He opened the medicine cabinet, took out toothbrush and toothpaste. “What’s in the bakery box?” he said.

“Éclairs. I bought them to soften you up.”

He uncapped the toothpaste and turned on the faucet. “I thought you liked me better hard.”

“Ha, ha. Very funny.”

“If you think that’s funny, you should see my summer stand-up act in the Adirondacks.”

“I’m sure it’s a scream and a half.”

I waited until he was done brushing his teeth, watched him as he leaned over the sink and splashed cold water all over his face. New as it was, this kind of familiarity still felt odd. Awkward. A little too intimate. I turned my face away from his reflection and said, “Tom?”

He put away his toothbrush and toothpaste, wiped down the marble counter, and tossed the washcloth into the hamper. Still shirtless, he leaned against the door frame, towel in hand. “What?”

I took a deep breath. Might as well jump right in with both feet. “Why didn’t you tell me the truth about Beth?”

I’d caught him by surprise. I could see it in his eyes. He finished drying his hands and returned the towel to its hook in the bathroom. “What truth?” he said.

“Oh, for the love of God. You know what truth. She killed herself.”

His gaze was cool. “Yes,” he said. “She did.”

“It would have been nice if you’d bothered to tell me. It was a little disconcerting, hearing it from someone else.”

He shoved both hands into the pockets of his pants. “Who told you?”

“Her sister, Melanie.”

“And I bet she told you exactly what she thinks of me. That I’m just as responsible for Beth’s death as if I’d shoved her off that bridge railing myself.”

“That might have come up somewhere in the conversation. She’s clearly not one of your biggest fans. Damn it, Tom, why didn’t you tell me?”

His expression remained emotionless, as if I were a stranger. “The time just never seemed right.”

“She was so smug about the fact that you’d lied to me. As though it corroborated her ridiculous accusations. I felt like a fool.”

“I didn’t lie to you. I just didn’t tell you everything.”

“In the end, what’s the difference? I still ended up looking like a fool. Damn it, Tom, she blindsided me.”

“What the hell do you want me to say, Jules? Maybe I should’ve turned to you that first night and said, Hi, I’m Tom. My wife was so miserable living with me that she killed herself. Say, can I buy you a drink? That would’ve gone over really well.”

“I’m not saying you should have dumped it in my lap during the first five minutes of our acquaintance. But somewhere between dinner that night and our wedding, you might’ve found the time to tell me.”

“I might have. I chose not to. You know, Jules, the world doesn’t revolve around you. Other people have feelings, too. Talk about being blindsided! Instead of confiding in me, my wife—the woman I loved, the mother of my children—decided to jump off a bridge. How the hell do you think that made me feel?”

The guilt was instantaneous. If I thought this was difficult for me, I could only imagine how hard it must be for Tom. He had to live with it every day for the rest of his life, the knowledge that Beth didn’t love him or their children enough to keep trying.

“I’m just a man, Jules,” he said. “I’m not perfect. Sometimes you scare me. Your expectations are so high. I can’t possibly live up to the image you have of me.”

I slid off the edge of the bed and crossed the room to him. The hurt in his eyes tore at my insides. I rested a hand against his chest, felt the strong, steady beat of his heart. “I’m sorry,” I said, embarrassed by the tears I was fighting back. “It must have been awful for you. I’m so very, very sorry.”

“Aw, Jules.” He wrapped his arms around me and rested his chin on top of my head. “That’s the real reason I didn’t tell you. It was just too damn hard to talk about it. And the last thing I wanted was your pity.”

“Pity is not something I feel for you. Trust me.”

“I have my pride. Maybe that’s wrong, but I can’t help it. I’m a man. I don’t like to show weakness, and I don’t like to complain. No matter what life throws at me, I deal with it.” His arms tightened around me. “And of course, I know that for the most part, I’ve been lucky.”

It was true. Tom had been blessed with a fine mind, a handsome face, a healthy body and an education that not everybody could afford. Two beautiful daughters, an extended family who loved him, in spite of their differences. A lucrative and satisfying career, a lovely house and a new wife who would walk over hot coals for him.

The only fly I could find in that particular ointment was the first wife who’d killed herself.

But that was then. This was now. A new beginning, a new life. Tossing aside logic and operating strictly from emotion, I stretched up on my toes and wrapped my arms around his neck. Tonight, Tom needed comforting. Regardless of our differences, we were husband and wife. I’d agreed to stand by him, in good times and bad. And the kind of comfort he needed tonight, only I could offer.

He raised his head, looked into my eyes, and smiled.

And I took his hand and led him to the bed.

They say that make-up sex is the best kind.

It must be true, because that night there was a poignancy to our lovemaking that hadn’t been there before. We’d weathered a storm together and, perhaps because it reminded us of the fragility of life and the uncertainty of relationships, it had brought us closer. Left us more attuned to each other.

Our marriage was solid. I had no doubts about marrying Tom; this was a forever thing. We’d had a little spat, but that was an inevitable result of couple-hood. It might be the first, but it wouldn’t be the last. Marriage isn’t a static thing; it’s a fluid entity, one that involves continual adjustments and constant negotiations.

Tonight, we’d foregone all that in the name of something more primal. It wasn’t until later, after the éclairs were gone and Tom was sleeping silently beside me, that I realized we’d never gotten around to discussing Riley’s accusations. We hadn’t gotten around to discussing much of anything. The aforementioned make-up sex had taken precedence over everything verbal. We’d let our bodies do the talking for us.