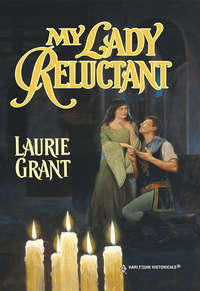

My Lady Reluctant

A log loomed ahead of them, and Gisele tried in vain to persuade the mare away from it by pressure from her knees and tugging on her mane, but having come so far on her own impulses, the palfrey was seemingly loath to start taking direction now. The horse gathered herself and leaped the log, with Gisele clinging like a burr atop her, but then caught her hoof in a half-buried root at her landing point on the other side.

Whinnying in fear, the mare cartwheeled, her long legs flailing. Gisele had no chance to do more than scream as she went flying through the air, striking the bole of a beech with the side of her head. There was a flash of light, and then—nothing.

Chapter Two

Gisele awoke to a gentle nudge against her shoulder. Lark? But no, she thought, keeping her eyes closed, whatever pushed against her shoulder was harder than the soft velvety nose of her palfrey. More like a booted foot…

The outlaws had found her, and were poking her to see if she lived. She froze, holding her breath. In a moment they would try some more noxious means of eliciting a response, and she would not be able to hold back her scream. Doubtless that would delight them.

She waited until her lungs burned for lack of air, then took a breath, eyes still closed.

“The lady lives, my lord.”

“So ’twould seem.”

They spoke good Norman French, not the gutteral Saxon tongue of the outlaws. Gisele’s eyes flew open.

And looked directly up into eyes so dark and deep that they appeared to be black, bottomless pools. The man who owned such eyes stood over her, gazing down at her with open curiosity. He had a warrior’s powerful shoulders and broad chest, and from Gisele’s recumbent position he seemed tall as a tree. He wore a hauberk, and the mail coif framed a face that was all angular planes. The lean, chiseled face, firm mouth, and deep-set eyes shouldn’t have been a pleasing combination, but despite the lack of a smile, it was.

Next to him, the other man who had spoken leaned over to stare at her, too. Even taller than the man he had addressed as my lord, he was massively built, and wore a leather byrnie sewn with metal links rather than a hauberk. Possibly a half-dozen years younger than his master, he was not handsome, but his face bore a stamp of permanent amiability.

“Who—who are you?” Gisele asked at last, when it seemed their duel of gazes might go on until the end of the world.

“I might ask the same of you,” the mail-clad man pointed out.

Gisele wondered if she should tell him the truth. By his speech, the quality of his armor, and the presence of the gold spurs, she could tell he was noble, but whose vassal was he? If he was Stephen’s and found out she was the daughter of a vassal of Matilda’s, would he still behave chivalrously toward her, or treat her with dishonor? She dared not tell him a lie, for in the leather pouch that swung from her girdle, she bore a letter her father had written to introduce her to the empress. If the man standing over her was the dishonorable sort, he might have already have searched that pouch for valuables, and discovered her identity and her allegiance. But he did not look unscrupulous, despite the slight impatience that thinned his lips now.

“I am Lady Sidonie Gisele de l’Aigle. And you?”

He went on studying her silently, until the other man finally said, “He’s the Baron de Balleroy, my lady. What are you doing in the woods all alone?”

“Hush, Maislin. Forgive my squire his impertinence, Lady Gisele. My Christian name is Brys, since you have given me yours. Might I help you to your feet?” he asked, extending a mail-gauntleted hand.

Up to this point Gisele hadn’t moved from her supine position, but as she pushed up on her elbows preparatory to taking his hand, it suddenly seemed as if the devil had made a Saracen drum out of her head and was pounding it with fiendish glee. With a moan she sank back, feeling sick with the intensity of the pain.

“She’s ill, my lord!” the squire announced anxiously.

“I can see that,” she heard de Balleroy snap. “Go catch her palfrey grazing over there, Maislin, while I see what’s to be done. I can see that your face is scraped, my lady, but where else are you hurt? Is aught broken?”

She opened her eyes again to find de Balleroy crouching beside her, his face creased with concern. He was reaching a hand out as if to explore her limbs for a fracture.

“Nay, ’tis my head,” she told him quickly, before he could touch her. “It feels as if it may split open. I…my palfrey fell, and I with her. I…guess the fall knocked me insensible. How long have I lain—” she began, as she struggled to sit up again.

“Just rest there a moment, Lady Sidonie,” he began.

“Gisele,” she corrected him.

He looked blank for a moment, until she explained, “I go by my middle name, Gisele. I was named Sidonie for my mother, but to avoid confusion, I am called Gisele.” There hadn’t been, of course, any confusion in the ten years that her mother had been dead, but de Balleroy needn’t know that.

She started to lever herself into a sitting position, but he put a hand on her shoulder to forestall her. “As to how long you lay there, I know not—but ’tis late afternoon now. And as my squire asked, what were you doing in the Weald alone?” There was an edge to his voice, as if he already suspected her answer.

And then she remembered. “Fleurette! I must go to her! And the men! Maybe I was wrong—even now, one or two may still live!” She thrashed now beneath his hand, struggling to get up, her teeth gritted against the pain her movement elicited.

“Lie still, my lady! You gain nothing if the pain makes you pass out again! You traveled with that party of men-at-arms, and the old woman? My squire and I…well, we came upon them farther back, Lady Gisele. There is nothing you can do for them. They are all dead.”

He could have added, And stripped naked as the day they were born, their throats cut, but he did not. Lady Sidonie Gisele de l’Aigle’s creamy ivory skin had a decidedly green cast to it already. If he described the scene of carnage he and his squire had found, she just might perish from the shock.

She ceased trying to rise. Her eyelids squeezed shut, forcing a tear down her cheek, then another. “We were set upon by brigands, my lord,” she said, obviously struggling not to give way to full-blown sobbing. “They jumped out of the trees without warning. I saw the arrow pierce my old nurse’s breast…but I hoped…”

“Like as not she was dead before she hit the ground, my lady.” Brys de Balleroy said, keeping his voice deep and soothing. “I’ll come back and see them buried, I promise you. But now we must get you to safety—’twill be dusk soon, and we must not remain in the woods any longer. Do you think you can stand?”

She nodded.

“Let me help you,” he told her, placing both of his hands under her arms to help her up. Over his shoulder, Brys saw that his squire had caught the chestnut mare and stood holding the reins nearby, his face anxious.

Lady Gisele gave a gallant effort, but as she first put her weight on her left foot, she gasped and swayed against him. “My ankle—I cannot stand on it!” Pearls of sweat popped out on her forehead as he eased her to the ground. Her face went shroud-white, her pupils dilated.

Leaving her in a sitting position, he went to her foot and began to pull the kidskin boot off.

She moaned and grabbed for his hand. “Nay, it hurts too much….”

He took the dagger from his belt and slit the kidskin boot open from top to toe, peeling the ruined boot from around her swollen ankle before probing the bone with experienced fingers.

He looked up to see her gritting her teeth and staring at him with pain-widened eyes. “’Tis but sprained, I think, my lady, though I doubt not it pains you, for ’tis very swollen. You cannot ride your mare, that’s clear, so you will have to ride with me.”

“But surely if you’ll just help me to mount, I can manage,” she insisted, trying once again to rise.

“You’ll ride with me,” he said, his face set. “You still look as if you could swoon any moment now, and I have no desire to be benighted in this forest with no one but me and my squire to fend off those miscreants. They may come looking for you, you know, so I’ll hear no more argument. Maislin, tie her palfrey to a tree and bring Jerusalem over. I’ll mount and you can lift her up behind me, then lead her mare. You can manage to ride pillion, can’t you, Lady Gisele? I’d hold you in front of me, but I’d rather have my arms free in case your attackers try again before we get out of the wood.”

She nodded, her eyes enormous in her pale oval face. Brys could not tell what hue they were, not in this murky gloom, but he could see she was beautiful, despite the rent and muddied clothes she wore. She had a pert nose, high cheekbones and lips that looked made for a man’s kiss. Beneath the gold fillet and the stained veil which was slightly askew, a wealth of rich brown hair cascaded down her back, much of it loose from the thick plait which extended nearly to her waist.

Once Brys was mounted on his tall black destrier, Maislin lifted Lady Gisele up to him from the stallion’s near side, his powerfully muscled arms making the task look effortless.

“Put your arms about my waist, my lady,” Brys instructed her. “Jerusalem’s gait is smooth, but ’twill steady you as we ride.”

A faint essence wafted to his nostrils, making him smile in wonder. After all she had been through, Lady Gisele de l’Aigle still smelled of lilies. He felt her arms go around him and saw her hands link just above his waist; then felt the slight pressure of her head, and farther down, the softness of her breast against his back. God’s blood, what a delicious torment of a ride this would be!

“You have not said how you came to be here, Lady Gisele,” he said, once they had found the path that led out of the Weald.

He felt her tense, then sigh against his back. He could swear the warmth of her breath penetrated his mail, the quilted aketon beneath, and all the way to his backbone.

“I suppose I owe you that much,” she said at last. “But I must confess myself afraid to be candid, my lord. These are dangerous times….”

Stung by her remark, he said, “Lady, I do not hold my chivalry so cheaply that I would abandon you if I liked not your reason for being in this wood with such a paltry escort. And even if I wanted to, Maislin wouldn’t allow it. He aspires to knighthood and his chivalry, at least, is unsullied.”

He heard her swift intake of breath. “I’m sorry,” she said at last. “I have offended you, and ’twas not my intent, when you have offered me only kindness. But even in Normandy we are aware of the trouble in England, as one noble fights for Stephen, the other for the empress. I know not which side you cleave to, my lord, though I know I am at your mercy whichever it is.”

The idea of this demoiselle being at his mercy appealed to him more than he cared to admit. Aloud, he said, “Then I will tell you I am a vassal of the empress. Does that aid you to trust me? I swear upon the True Cross you have naught to fear of me, even if you are one of Stephen’s mistresses.”

He felt her relax against him like a full grain sack that suddenly is opened at the bottom. “No, I am assuredly not one of those. The de l’Aigles owe their loyalty to Matilda as well, Lord Brys. In fact, I am sent to join her as a lady-in-waiting.”

“Then we are on the same side. ’Tis well, is it not? And better yet, I am bound for London with a message for the empress, so I will consider it my honor to escort you to her court.”

“Our Lord and all His saints bless you, Lord Brys,” she murmured. “I will write to my father, and ask him to reward your kindness.”

“’Tis not necessary, lady. Any Christian ought to do the same,” he said. He felt himself begin to smile. “I am often with her grace, so we shall see each other on occasion. If I can but claim a smile from you each time I come, I shall ask no other recompense.” He could tell, from the shy way she had looked at him earlier, that she was a virgin. Alas. Lady Gisele, if only you were a noble widow instead of an innocent maiden, I’d ask an altogether different reward when I came to court. Brys felt his loins stir at the thought.

Behind him, he heard Maislin give a barely smothered snort, and knew his squire was struggling to contain his amusement at the fulsome remark. He would chasten him about it later, Brys was sure.

“And when did you come to England, Lady Gisele?” he asked, thankful she was riding behind him and could not see the effect his thoughts had on his body.

“We landed at Hastings but this morning, my lord.”

Brys considered that. “Lady Gisele, forgive me for asking, but if your father is as aware of the conditions here as you say, why would he send you with but half a dozen men and an old woman?”

She was silent, and Brys knew his words had been rude. What daughter could allow a parent to be criticized? “I’m sorry if I sounded harsh—”

“Nay, do not apologize, for you are right. There should have been a larger escort. I know that had my horse not bolted, I would have been lucky to escape those brigands with my life, let alone my honor.” Her voice was muffled, as if she fought tears. “Poor Fleurette—to have died because of my father’s…misalculation. And those six men, too. They did not deserve to perish like that, all unshriven.”

He was ready to swear she’d meant some other word when she’d said miscalculation, and he wondered what it was—and what was wrong with the Count de l’Aigle that he valued his daughter so cheaply.

“You have a tender heart, lady.” He only hoped it would not lead her astray at Matilda’s court.

“Fleurette had been my nurse from my earliest childhood, so ’tis natural I would grieve at her death,” she said, sounding a trifle defensive. “The men…well, I have difficulty accepting that because my lord father ordered them to escort me to London, they lie dead now.”

This was an uncommon noblewoman, to spare a thought for common soldiers. “Dying violently is the risk any man-at-arms runs, but doubtless their loyalty will outweigh their sins, Lady Gisele.”

“God send you are right.”

Perhaps it was best not to allow her to dwell on such things right now. After a moment he said, “You go to court to wed, my lady?”

He felt her stiffen against his back. He glanced back over his shoulder and saw that her eyes had the light of defiance dancing in them.

“’Twas my father’s wish, my lord.”

He was quick to catch the implication. “But not yours?” he asked, glancing over his shoulder again.

He saw her shrug. “I shall have a place at the empress’s court,” she said. “That will be enough for me. What need have I for some lord to carry me off to his castle to bear a child every year till I am no longer able?”

An image flashed before his mind’s eye of this woman nursing a babe—his babe. Sternly he banished the picture before he grew too fond of it. There was no place in his life for such feelings, and the lady had just indicated there was none in the life she wanted, either. But he could not stop himself from probing further, though in a carefully neutral tone of voice, “You do not wish to fulfill the role that nature and the church has deemed fit for a woman?”

“There must be more for a woman than the marriage bed or the convent, no matter what the church tells us,” she said with a passionate insistence. “There must be.”

“Lady, has a man hurt you in some manner?” he asked in a low tone that would not carry to Maislin’s ears. Had he been wrong about her? Had some man robbed her of her innocence?

Her answer came a little too quickly. “Hurt me? Nay, my lord! Just because the lord the empress selected for me chose to marry some other lady, you should not think that I am not heart-whole.”

She was lying, he’d wager his salvation on that. There was a wealth of wounded pride in her voice. But something about her last few words sounded familiar….

“Nay, my lord,” she went on in a breezy voice, “’Tis merely that I see no need to w—”

Suddenly he realized who she was. “Ah, you’re the one Matilda offered to Baron Alain of Hawkswell, aren’t you?”

“And how did you know such a thing?” she asked, her voice chilly.

He felt her remove her arms from about his waist and draw a little away from him. Instantly his body felt deprived. He wanted to demand that she put her arms back around him—he didn’t want her to fall, of course!

“Fear not, proud lady—’tis not a thing bandied about court—the only reason I know is that Alain is a good friend.”

“How nice for you to have such a friend,” she said, as if every courteous word cut her like a dagger.

“Nay, do not bristle at me,” he said, patting her hands that were still clasped around his abdomen with his free one. “Alain would not have suited you at all—a widower with two children? Claire is much more his sort, for all that her family are adherents of Stephen’s. You’ll see what I mean if you ever meet them.”

“Mayhap,” she said noncommittally, but he could tell she was lying again. She’d move heaven and earth to avoid encountering the man who had rejected her, sight unseen. What a proud, fierce maid she was!

“I think you have the right idea, Lady Gisele—enjoy your life at court just as any bachelor knight enjoys his freedom,” he told her. “You’ll enjoy the empress’s favor and all her lords will covet you.”

“I told you,” she began, impatience tingeing her voice, “I care not about the opinion of men—”

“Of course, of course,” he said. “Hold to that course, my lady, for we are knaves one and all.” But Brys could guess how Lady Gisele’s coolness would affect the men in the empress’s orbit—they’d be panting all the more after Gisele de l’Aigle, like brachets after a swift doe. He felt acid burn in his stomach at the thought. And Brys could only wonder how long Matilda would allow such a beauty to indulge her whims before she used her as a pawn in making an alliance.

Chapter Three

At last they came to a Benedictine priory just beyond the edge of the Weald. Gisele, exhausted by the day’s events and longing to have some time to grieve in private, told Brys before he even assisted her to dismount that she was too tired to dine in the guest house and would seek her bed early instead.

“Very well, then, my lady,” he said. “Doubtless you’ll feel better on the morrow. I will send the infirmarer to you with a salve for your cuts and a draft to help you sleep. Your ankle will have swollen since this afternoon, and the pain is apt to keep you wakeful.”

“You seem very familiar with what this house has to offer, my lord,” she said. Now that they were beyond the forest gloom, she saw that his eyes were not black, but a deep, rich brown, like the color of her palfrey’s coat.

“I have sought remedy for injury here before,” he said, without elaborating.

She could tell that Brother Porter was scandalized by the way de Balleroy handed her down to his squire, then took Gisele back into his arms and bid the monk to lead the way to the ladies’ guest quarters. But the disapproving Benedictine did not remonstrate with him, just directed another pair of monks to stable the horses, before gesturing for de Balleroy to follow him.

Gisele awoke and hobbled her way to the shuttered window, throwing it open to see if it was yet light. She was alarmed to see that the sun was already high in the sky. The infirmarian’s potion had been powerful indeed! She hadn’t even heard the chapel bells call the brothers to prayer during the night. Her ankle still throbbed, though less than it had last even.

Then a sudden thought struck her. Dear God, what if Brys de Balleroy had grown tired of waiting and had ridden on to London without her? What of his promise to have Fleurette and the men-at-arms buried?

Hopping awkwardly over to the row of hooks by the door where she had left her muddied, torn gown hanging, she found the garment miraculously clean and dry again. Propped up against the wall beneath the gown was a crutch with a cloth-padded armrest. She silently blessed whichever Benedictines had done her these kindnesses, and with the crutch to help her, ventured out into the cloister and across the garth until she came to the gate.

“Where is my lord de Balleroy? Has he left?” she asked Brother Porter.

“Aye,” replied the monk. “He and the big fellow, his squire, left at Prime—along with a wagon and a pair of our brothers. He said he promised you he would bury your dead. Some other brothers are already digging the graves in our cemetery.”

“Oh.” So de Balleroy was as good as his word, Gisele thought, warmed by the idea that he had been up and about and fulfilling his promise while she had still been deep in slumber.

The party returned at midday. Gisele, waiting just inside the gate, saw a grim-faced de Balleroy riding behind the mule-drawn cart with its ghastly load.

“Make ready to leave, Lady Gisele,” he said as he dismounted.

“But may we not remain until they are buried? Fleurette—” she began, her voice breaking as she saw the monks begin to unload the sheet-wrapped, stiffened forms. She could not even tell which one was her beloved nurse.

“Is at peace already, my lady, and if we stay for the burial we will have to spend another night here. We will have to pass one more night on the road as ’tis, and I think it best to get you to the empress as soon as I can. Do not fear, the Benedictines will see all done properly.”

She could see the prudence of that, of course, but nevertheless, her heart ached as she rode away from the priory within the hour, once more riding pillion behind de Balleroy.

The next day, as the distant spires of London came into view ahead of them, de Balleroy turned west.

“We do not go directly to London?” Gisele questioned.

“Nay. The empress resides at Westminster, a few miles up the Thames, my lady,” de Balleroy told her. “But you’ll see the city soon and often enough. Now that Matilda has finally been admitted to London, and will soon be crowned, she likes to remind the citizens of her presence.”

Gisele nodded her understanding and reined her palfrey to the left, where the road led over marshy, sparsely settled ground. Though her ankle was still slightly swollen and painful, she had insisted she would sit her own horse this morning, not wanting to arrive at the empress’s residence riding pillion behind the baron as if she had no more dignity than a dairymaid. It was bad enough that outlaws possessed every stitch of clothing she owned, except for what she had on her back. Seeing her in the enforced intimacy of this position, however, someone might take them for lovers. Having her good name ruined would not be a good way for Gisele to begin her new life!

Perhaps de Balleroy had guessed her thoughts this morning. Instead of arguing about her ankle’s fitness, he had lifted her up into her saddle as if she weighed no more than an acorn, sparing her the necessity of putting her weight on the still-tender ankle to mount.

Gisele took the opportunity to study de Balleroy covertly, an easier task now that she was no longer sitting behind him. The sun gleamed on his chin-length, auburn hair. Somehow she had not expected it to be such a hue; his dark eyes and eyelashes had given no hint of it, and she had never previously seen him without his head being covered. This morning, however, he had evidently felt close enough to civilization to leave the metal coif draped around his neck and shoulders.

“Faith, but ’tis hot this morn,” he murmured, raking a hand through his hair, an action which caused the sun to gild it with golden highlights that belied the dangerous look of his lean, beard-shadowed cheeks. “I believe the sun is shining just to welcome you to court, Lady Gisele.” He flashed a grin at her, making her heart to do a strange little dance within her breast.

Firmly she quashed the flirtatious reply that had sprung ready-born to her lips. She owed this man much for her safety, but it would not do to let him think his flattery delighted her, after telling him before that such things were unimportant to her. From the ease at which such smooth words flowed from his lips, she supposed he had pleased many women with his cajolery—but she was not going to join their number!