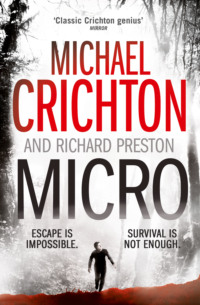

Micro

Chapter 1

Divinity Avenue, Cambridge

18 October, 1:00 p.m.

In the second-floor biology lab, Peter Jansen, twenty-three, slowly lowered the metal tongs into the glass cage. Then, with a quick jab, he pinned the cobra just behind its hood. The snake hissed angrily as Jansen reached in, gripped it firmly behind the head, raised it to the milking beaker. He swabbed the beaker membrane with alcohol, pushed the fangs through, and watched as yellowish venom slid down the glass.

The yield was a disappointing few milliliters. Jansen really needed a half-dozen cobras in order to collect enough venom to study, but there was no room for more animals in the lab. There was a reptile facility over in Allston, but the animals there tended to get sick; Peter wanted his snakes nearby, where he could supervise their condition.

Venom was easily contaminated by bacteria; that was the reason for the alcohol swab and for the bed of ice the beaker sat on. Peter’s research concerned bioactivity of certain polypeptides in cobra venom; his work was part of a vast research interest that included snakes, frogs, and spiders, all of which made neuroactive toxins. His experience with snakes had made him an “envenomation specialist,” occasionally called by hospitals to advise on exotic bites. This caused a certain amount of envy among other graduate students in the lab; as a group, they were highly competitive and quick to notice if anyone got attention from the outside world. Their solution was to complain that it was too dangerous to keep a cobra in the lab, and that it really shouldn’t be there. They referred to Peter’s research as “working with nasty herps.”

None of this bothered Peter; his disposition was cheerful and even-handed. He came from an academic family, so he didn’t take this backbiting too seriously. His parents were no longer alive, killed in the crash of a light plane in the mountains of Northern California. His father had been a professor of geology at UC Davis, and his mother had taught on the medical faculty in San Francisco; his older brother was a physicist.

Peter had returned the cobra to the cage just as Rick Hutter came over. Hutter was twenty-four, an ethnobotanist. Lately he had been researching analgesics found in the bark of rain-forest trees. As usual, Rick was wearing faded jeans, a denim shirt, and heavy boots. He had a trimmed beard and a perpetual frown. “I notice you’re not wearing your gloves,” he said.

“No,” Peter said, “I’ve gotten pretty confident—”

“When I did my field work, you had to wear gloves,” he said. Rick Hutter never lost an opportunity to remind others in the lab that he had done actual field work. He made it sound as if he had spent years in the remote Amazon backwaters. In fact, he had spent four months doing research in a national park in Costa Rica. “One porter in our team didn’t wear gloves, and reached down to move a rock. Bam! Terciopelo sunk its fangs into him. Fer-de-lance, two meters long. They had to amputate his arm. He was lucky to survive at all.”

“Uh-huh,” Peter said, hoping Rick would get going. He liked Rick, but the guy had a tendency to lecture everybody.

The person in the lab who really disliked Rick Hutter was Karen King. Karen, a tall young woman with dark hair and angular shoulders, was studying spider venom and spiderwebs. She overheard Rick lecturing Peter on snakebite in the jungle, and couldn’t stand it. She had been working at a lab bench, and she snapped over her shoulder, “Rick—you stayed in a tourist lodge in Costa Rica. Remember?”

“Bullshit. We camped in the rain forest—”

“Two whole nights,” Karen interrupted him, “until the mosquitoes drove you back to the lodge.”

Rick glared at Karen. His face turned red, and he opened his mouth to say something, but didn’t. Because he couldn’t reply. It was true: the mosquitoes had been hellish. He’d been afraid the mosquitoes might give him malaria or dengue hemorrhagic fever, so he had gone back to the lodge.

Instead of arguing with Karen King, Rick turned to Peter: “Hey, by the way. I heard a rumor that your brother is coming today. Isn’t he the one who struck it rich with a startup company?”

“That’s what he tells me.”

“Well, money isn’t everything. Myself, I’d never work in the private sector. It’s an intellectual desert. The best minds stay in universities so they don’t have to prostitute themselves.”

Peter wasn’t about to argue with Rick, whose opinions on any subject were strongly held. But Erika Moll, the entomologist who’d recently arrived from Munich, said, “I think you are being rigid. I wouldn’t mind working for a private company at all.”

Hutter threw up his hands. “See? Prostituting.”

Erika had slept with several people in the biology department, and didn’t seem to care who knew. She gave him the finger and said, “Spin on it, Rick.”

“I see you’ve mastered American slang,” Rick said, “among other things.”

“The other things, you wouldn’t know,” she said. “And you won’t.” She turned to Peter. “Anyway, I see nothing wrong with a private job.”

“But what is this company, exactly?” said a soft voice. Peter turned and saw Amar Singh, the lab’s expert in plant hormones. Amar was known for his distinctly practical turn of mind. “I mean, what does the company do that makes it so valuable? And this is a biological company? But your brother is a physicist, isn’t he? How does that work?”

At that moment, Peter heard Jenny Linn across the lab say, “Wow, look at that!” She was staring out the window at the street below. They could hear the rumble of high-performance engines. Jenny said, “Peter, look—is that your brother?”

Everyone in the lab had gone to the windows.

Peter saw his brother on the street below, beaming like a kid, waving up at them. Eric was standing alongside a bright yellow Ferrari convertible, his arm around a beautiful blond woman. Behind them was a second Ferrari, gleaming black. Someone said, “Two Ferraris! That’s half a million dollars down there.” The rumble of the engines echoed off the scientific laboratories that lined Divinity Avenue.

A man stepped out of the black Ferrari. He had a trim build and expensive taste in clothes, though his look was decidedly casual.

“That’s Vin Drake,” Karen King said, staring out the window.

“How do you know?” Rick Hutter said to her, standing beside her.

“How do you not know?” Karen replied. “Vincent Drake is probably the most successful venture capitalist in Boston.”

“You ask me, it’s a disgrace,” Rick said. “Those cars should have been outlawed years ago.”

But nobody was listening to him. They were all heading for the stairs, hurrying down to the street. Rick said, “What is the big deal?”

“You didn’t hear?” Amar said, hurrying past Rick. “They’ve come here to recruit.”

“Recruit? Recruit who?”

“Anybody doing good work in the fields that we’re interested in,” Vin Drake said to the students clustered around him. “Microbiology, entomology, chemical ecology, ethnobotany, phytopathology—in other words, all research into the natural world at the micro- or nano-level. That’s what we’re after, and we’re hiring now. You don’t need a PhD. We don’t care about that; if you’re talented you can do your thesis for us. But you will have to move to Hawaii, because that’s where the labs are.”

Standing to one side, Peter embraced his brother, Eric, then said, “Is that true? You’re already hiring?”

The blond woman answered. “Yes, it’s true.” She stuck out her hand and introduced herself as Alyson Bender, the CFO of the company. Alyson Bender had a cool handshake with a crisp manner, Peter thought. She wore a fawn-colored business suit with a string of natural pearls at her neck. “We need at least a hundred first-rate researchers by the end of the year,” she said. “They’re not easy to find, even though we offer what is probably the best research environment in the history of science.”

“Oh? How is that?” Peter said. It was a pretty big claim.

“It’s true,” his brother said. “Vin will explain.”

Peter turned to his brother’s car. “Do you mind…” He couldn’t help himself. “Could I get in? Just for a minute?”

“Sure, go ahead.”

He slipped behind the wheel, shut the door. The bucket seat was tight, enveloping; the leather smelled rich; the instruments were big and business-like, the steering wheel small, with unusual red buttons on it. Sunlight gleamed off the yellow finish. Everything felt so luxurious, he was a little uneasy; he couldn’t tell if he liked this feeling or not. He shifted in the seat, and felt something under his thigh. He pulled out a white object that looked like a piece of popcorn. And it was light like popcorn, too. But it was stone. He thought the rough edges would scratch the leather; he slipped it into his pocket and climbed out.

One car over, Rick Hutter was glowering at the black Ferrari, as Jenny Linn admired it. “You must realize, Jenny,” Rick said, “that this car, squandering so many resources, is an offense against Mother Earth.”

“Really?” Jenny said. “Did she tell you that?” She ran her fingers along the fender. “I think it’s beautiful.”

In a basement room furnished with a Formica table and a coffee machine, Vin Drake had seated himself at the table, with Eric Jansen and Alyson Bender, the two Nanigen executives, placed on either side of him. The grad students clustered around, some sitting at the table, some leaning against the wall.

“You’re young scientists, starting out,” Vin Drake was saying. “So you have to deal with the reality of how your field operates. Why, for example, is there such an emphasis on the cutting edge in science? Why does everybody want to be there? Because all the prizes and recognition go to new fields. Thirty years ago, when molecular biology was new, there were lots of Nobels, lots of major discoveries. Later, the discoveries became less fundamental, less groundbreaking. Molecular biology was no longer new. By then the best people had moved on to genetics, proteomics, or to work in specialized areas: brain function, consciousness, cellular differentiation, where the problems were immense and still unsolved. Good strategy? Not really, because the problems remain unsolved. Turns out it isn’t enough that the field is new. There must also be new tools. Galileo’s telescope—a new vision of the universe. Leeuwenhoek’s microscope—a new vision of life. And so it continues, right to the present: radio telescopes exploded astronomical knowledge. Unmanned space probes rewrote our knowledge of the solar system. The electron microscope altered cell biology. And on, and on. New tools mean big advances. So, as young researchers, you should be asking yourselves—who has the new tools?”

There was a brief silence. “Okay, I’ll bite,” someone said. “Who has the new tools?”

“We do,” Vin said. “Nanigen MicroTechnologies. Our company has tools that will define the limits of discovery for the first half of the twenty-first century. I’m not kidding, I’m not exaggerating. I’m telling you the simple truth.”

“Pretty big claim,” Rick Hutter said. He leaned against the wall, arms folded, clutching a paper cup of coffee.

Vin Drake looked calmly at Rick. “We don’t make big claims without a reason.”

“So what exactly are your tools?” Rick went on.

“That’s proprietary,” Vin said. “You want to know, you sign an NDA and come to Hawaii to see for yourself. We’ll pay your airfare.”

“When?”

“Whenever you’re ready. Tomorrow, if you want.”

Vin Drake was in a hurry. He finished the presentation, and they all filed out of the basement and went out onto Divinity Avenue, to where the Ferraris were parked. In the October afternoon, the air had a bite, and the trees burned with orange and russet colors. Hawaii might have been a million miles from Massachusetts.

Peter noticed Eric wasn’t listening. He had his arm around Alyson Bender, and he was smiling, but his thoughts were elsewhere.

Peter said to Alyson, “Would you mind if I took a family moment here?” Grabbing his brother’s arm, he walked him down the street away from the others.

Peter was five years younger than Eric. He had always admired his brother, and coveted the effortless way Eric seemed to manage everything from sports to girls to his academic studies. Eric never strained, never seemed to sweat or worry. Whether it was a playoff game for the lacrosse team, or oral exams for his doctorate, Eric always seemed to know how to play things. He was always confident, always easy.

“Alyson seems nice,” Peter said. “How long have you been seeing her?”

“Couple of months,” Eric said. “Yes, she’s nice.” Somehow, he didn’t sound enthusiastic.

“Is there a but?”

Eric shrugged. “No, just a reality. Alyson’s got an MBA. Truth is, she’s all business, and she can be tough. You know—Daddy wanted a boy.”

“Well, Eric, she’s very pretty for a boy.”

“Yes, she’s pretty.” That tone again.

Feeling around, Peter said, “And how’re things with Vin?” Vincent Drake had a somewhat unsavory reputation, had been threatened twice with federal indictments; he had beaten back prosecutors both times, although no one knew quite how. Drake was regarded as tough, smart, and unscrupulous, but above all, successful. Peter had been surprised when Eric first signed on with him.

“Vin can raise money like nobody else,” Eric said. “His presentations are brilliant. And he always lands the tuna, as they say.” Eric shrugged. “I accept the downside, which is that Vin will say whatever he needs to say to get a deal done. But lately he’s been, well…more careful. More presidential.”

“So he’s the president of the company, Alyson’s the CFO, and you’re—?”

“Vice president in charge of technology,” Eric said.

“Is that okay?”

“It’s perfect. I want to be in charge of the technology.” He smiled. “And to drive a Ferrari…”

“What about those Ferraris?” Peter said, as they approached the cars. “What’re you going to do with them?”

“We’ll drive them down the East Coast,” Eric said. “Stop at major university biology labs along the way, and do this little song-and-dance to drum up candidates. And then turn in the cars in Baltimore.”

“Turn them in?”

“They’re rented,” Eric said. “Just a way to get attention.”

Peter looked back at the crowd around the cars. “Works.”

“Yes, we figured.”

“So you really are hiring now?”

“We really are.” Again, Peter detected a lack of enthusiasm in his brother’s voice.

“Then what’s wrong, bro?”

“Nothing.”

“Come on, Eric.”

“Really, nothing. The company is underway, we’re making great progress, the technology is amazing. Nothing’s wrong.”

Peter said nothing. They walked in silence for a moment. Eric stuck his hands in his pockets. “Everything’s fine. Really.”

“Okay.”

“It is.”

“I believe you.” They came to the end of the street, turned, headed back toward the group clustered around the cars.

“So,” Eric said, “tell me: which one of those girls in your lab are you seeing?”

“Me? None.”

“Then who?”

“Nobody at the moment,” Peter said, his voice sinking. Eric had always had lots of girls, but Peter’s love life was erratic and unsatisfactory. There had been a girl in anthropology; she worked down the street at the Peabody Museum, but that ended when she started going out with a visiting professor from London.

“That Asian woman is cute,” Eric said.

“Jenny? Yes, very cute. She plays on the other team.”

“Ah, too bad.” Eric nodded “And the blonde?”

“Erika Moll,” Peter said. “From Munich. Not interested in an exclusive relationship.”

“Still—”

“Forget it, Eric.”

“But if you—”

“I already did.”

“Okay. Who’s the tall, dark-haired woman?”

“That’s Karen King,” Peter said. “Arachnologist. Studying spider web formation. But she worked on the textbook Living Systems. Kind of won’t let anybody forget it.”

“A little stuck-up?”

“Just a little.”

“She looks very buff,” Eric remarked, still staring at Karen King.

“She’s a fitness nut. Martial arts, gym.”

They were coming back to the group. Alyson waved to Eric. “You about ready, honey?”

Eric said he was. He embraced Peter, shook his hand.

“Where now, bro?” Peter said.

“Down the road. We have an appointment at MIT. Then we’ll do BU later in the afternoon, and start driving.” He punched Peter on the shoulder. “Don’t be a stranger. Come and see me.”

“I will,” Peter said.

“And bring your group with you. I promise you—all of you—you won’t be disappointed.”

Chapter 2

Biosciences Building

18 October, 3:00 p.m.

Returning to the lab, they experienced that familiar environment as suddenly mundane, old-fashioned. It felt crowded, too. The tensions in the lab had been simmering for a long time: Rick Hutter and Karen King had despised each other from the day they had arrived; Erika Moll had brought trouble to the group with her choice of lovers; and, like so many grad students everywhere, they were rivals. And they were tired of the work. It seemed they all felt that way, and there was a long silence as they each returned to their lab benches and resumed work in a desultory way. Peter took his milking beaker off the ice block, labeled it, and put it on his shelf of the refrigerator. He noticed something rattling around with the change in his pocket, and, idly, he took the object out. It was the little thing he’d found in his brother’s rented Ferrari. He flicked it across the bench surface. It spun.

Amar Singh, the plant biologist, was watching. “What’s that?”

“Oh. It broke off my brother’s car. Some part. I thought it would scratch the leather.”

“Could I see—?”

“Sure.” It was a little larger than his thumbnail. “Here,” Peter said, without looking at it closely.

Amar put it in the flat palm of his hand, and squinted at it. “This doesn’t look like a car part to me.”

“No?”

“No. I’d say it’s an airplane.”

Peter stared. It was so small he couldn’t really make out details, but now that he looked closely, it did indeed appear to be a tiny airplane. Like something from a model kit, the kind of kits he’d made as a boy. Maybe a fighter jet to glue onto an aircraft carrier. But if so, it was like no fighter jet he had ever seen. This one had a blunted nose, an open seat, no canopy, and a boxy rear with tiny stubby flanges: no real wings to speak of.

“Do you mind…”

Amar was already heading for the big magnifying glass by his workbench. He put the object under the glass, and turned it carefully. “This is quite fantastic,” he said.

Peter pushed his head in to look. Under magnification, the airplane—or whatever it was—appeared exquisitely beautiful, rich with detail. The cockpit had amazingly intricate controls, so minute it was hard to imagine how they had been carved. Amar was thinking the same thing.

“Perhaps laser lithography,” he said, “the same way they do computer chips.”

“But is it an airplane?”

“I doubt it. No method of propulsion. I don’t know. Maybe it’s just some kind of model.”

“A model?” Peter said.

“Perhaps you should ask your brother,” Amar said, drifting back to his workbench.

Peter reached Eric on his cell phone. He heard loud voices in the background. “Where are you?” Peter said.

“Memorial Drive. They love us at MIT. They understand what we’re talking about.”

Peter described the small object he had found.

“You really shouldn’t have that,” Eric said. “It’s proprietary.”

“But what is it?”

“Actually, it’s a test,” his brother said. “One of the first tests of our robotic technology. It’s a robot.”

“It looks like it has a cockpit, with a little chair and instruments, like someone would sit there…”

“No, no, what you’re seeing is the slot to hold the micro-power-pack and control package. So we can run it remotely. I’m telling you, Peter, it’s a bot. One of the first proofs of concept of our ability to miniaturize beyond anything previously known. I was going to show it to you if we had time, but—listen, I’d prefer you keep that little device to yourself, at least for now.”

“Sure, okay.” No point in telling him about Amar.

“Bring it with you when you come to visit us,” Eric said, “in Hawaii.”

The head of the lab, Ray Hough, came in and spent the rest of the day in his office, reviewing papers. By general agreement it was considered poor form for the graduate students to discuss other jobs while Professor Hough was present. So around four o’clock they all met at Lucy’s Deli on Mass Ave. As they crowded around a couple of small tables, a lively discussion ensued. Rick Hutter continued to argue that the university was the only place where one could engage in ethical research. But nobody really listened to him; they were more concerned with the claims that Vin Drake had made. “He was good,” Jenny Linn said, “but it was a sales pitch.”

“Yes,” Amar Singh said, “but at least one part of it was true. He’s right that discoveries do follow new tools. If those guys have the equivalent of a new kind of microscope, or a new PCR-type technique, then they’re going to make a lot of discoveries quickly.”

“But could it really be the best research environment in the world?” Jenny Linn said.

“We can see for ourselves,” Erika Moll said. “They said they’d pay airfare.”

“How’s Hawaii this time of year?” Jenny said.

“I can’t believe you guys are buying into this,” Rick said.

“It’s always good,” Karen King said. “I did my tae kwon do training in Kona. Wonderful.” Karen was a martial arts devotee, and had already changed into a sweat suit for her evening workout.

“I overheard the CFO say they’re hiring a hundred people before the end of the year,” Erika Moll said, trying to steer the conversation away from Karen and Rick.

“Is that supposed to scare us or entice us?”

“Or both?” Amar Singh said.

“Do we have any idea what this new technology is they claim to have?” Erika said. “Do you know, Peter?”

“From a career standpoint,” Rick Hutter said, “you’d be very foolish not to get your PhD first.”

“I have no idea,” Peter said. He glanced at Amar, who said nothing, just nodded silently.

“Frankly, I’m curious to see their facility,” Jenny said.

“So am I,” Amar said.

“I looked at their website,” Karen King said. “Nanigen MicroTech. It says they make specialized robots at the micro- and nano-scale. That’s millimeters down to thousandths of a millimeter. They have drawings of robots that look like they’re about four or five millimeters long—maybe a quarter of an inch. And then some that are half that, maybe two millimeters. The robots seem very detailed. No explanation how they could be made.”

Amar was staring at Peter. Peter said nothing.

“Your brother hasn’t talked to you about this, Peter?” Jenny asked.

“No, this has been his secret.”

“Well,” Karen King continued, “I don’t know what they mean by nano-scale robots. That would be less than the thickness of a human hair. Nobody can fabricate at those dimensions. You’d have to be able to construct a robot atom by atom, and nobody can do that.”

“But they say they can?” Rick said. “It’s corporate bullshit.”

“Those cars aren’t bullshit.”

“Those cars are rented.”

“I have to get to class,” Karen King said, standing up from the table. “I’ll tell you one thing, though. Nanigen has kept a very low profile, but there are a few brief references in some business sites, going back about a year. They got close to a billion dollars in funding from a consortium put together by Davros Venture Capital—”

“A billion!”

“Yeah. And that consortium is primarily composed of international drug companies.”

“Drug companies?” Jenny Linn frowned. “Why would they be interested in micro-bots?”