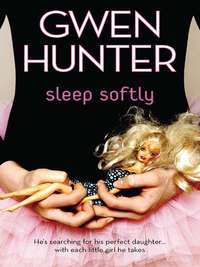

Sleep Softly

My breath came harsh and fast as the old dog’s pace increased. “Good boy, Cheeks,” I muttered, stumbling along behind him. “Good old dog.”

He pulled me down a dip, past a lichen-covered grouping of boulders cluttered with rain-collected debris from a recent storm. Back up over a freshly downed tree, its bark ripped through by lightning, its spring leaves withered.

We were surely near the edge of Chadwick Farms property by now, over near the original Chadwick homestead, close to the old Hilldale place. I could see open land through the trees off to one side and the tractor I had heard earlier sounded louder. Cheeks sped up again, his gait uneven as his degenerating hips fought the pace, and I broke into a sweat.

And then I smelled it. The smell of old death.

I reeled the leash back short, keeping Cheeks just ahead. The hair on his shoulders lifted higher and his breathing sped up, making little huffs of sound. His nose skimmed along the sandy soil. The old dog put off a strong scent of his own in his excitement.

Rounding two old oaks, Cheeks quivered and stopped. He had found a scrap of cloth, his nose was planted in it. Just beyond was a patch of disturbed soil, the fresh sand bright all around, darkened in the center. More cloth protruded from the darkened space.

“Oh, Jesus,” I whispered, pulling back on Cheeks to keep him close. “Oh, Jesus.” It was a prayer, the kind one says when there aren’t any real words, just horror and fear. Cheeks lunged toward the darkened spot in the sand, jerking me hard.

“No!” I gripped the leash fiercely and pulled Cheeks away, back beyond the two oaks. With their protection between me and the grave, I stopped. Legs quivering, I dropped to the sand and clutched the old dog close. I was crying, tears scudding down my face. “Someone’s little girl. Someone’s little girl. Oh, Jesus.”

Cheeks thrust his muzzle into my face, a high-pitched sound coming from deep in his throat, hurt and confused. I’d said no when he’d done what I wanted. Shouted when he had found what he’d been told to find.

“I’m sorry, Cheeks.” I lay my head against his face and he licked my tears once, his huge tongue slathering my cheek into my hairline. My arms went around him, my body shaking with shock, fingers and feet numb. “Good Cheeks. Good old boy. You’re a hero, yes you are. Sweet dog. Sweet Cheeks.”

I laughed, the sound shuddering. “Sweet Cheeks. Jas would tease me all week if she heard me call you that. But you are. A sweet, sweet dog.”

The hound stopped whining and lay beside me, his front legs across my thigh. The pungent effluvium of tired dog and death wrapped around me. The quiet of the woods enveloped me. I breathed deeply, letting the calm of the place find me and take hold, not thinking about the death only feet away.

After long minutes, the tingling in my hands and feet that indicated hyperventilation eased and I stood. I checked my compass, dug out the spray can of orange paint and marked both trees with two big Xs.

“Okay, Cheeks. I hope you can get me back to Mabel. Home,” I commanded. “Let’s go home.” When Cheeks looked up at me with no comprehension at all, I held my jeans-clad leg to him so he could sniff the horse and said, “Find. Find.” He was a smart dog, and without a single false start led me back along the sandy riverbed. With the bright paint, I marked each turn and boulder and tree on the path, back into the sunlight and the pasture.

3

I shared more Fig Newtons with Cheeks—not the best food for a dog, but not the worst, either—took the animals to the creek for water, and used the quiet time to compose myself before moving horse and dog to the edge of the woods near the sandy depression. Once there, Cheeks and Mabel and I remained in the shade of the trees and waited for law enforcement.

Cheeks had developed a bad limp and wouldn’t make it back to the barn on his own four feet. His medication was in the kitchen, too far away to do him any good, and I could tell he was in pain. Not much of a reward for a job well done. “There’s a price to be paid for every good deed, sweet Cheeks,” I said, stroking the hound. “You find a body, you get aching joints. And I’ll bet you the cops are going to be mad at us for finding the body in the first place.”

Cheeks just panted in the rising warmth, his huge tongue hanging out one side of his mouth. In the distance, I heard the unmistakable sound of engines. Standing, I tied the dog off near Mabel and waited at the edge of sunlight.

Johnny Ray led the way along the fence that marked the pasture, driving his old truck, a seventies-something battered Ford pickup that he couldn’t seem to kill, though the motor sounded like a sewing machine that was missing a beat, and the paint was rusted and dulled out to a weary, piebald brown. Behind him came unfamiliar vehicles, a white county van, two four-wheeled all-terrain vehicles, a sport utility vehicle. For the most part, they stayed off the crops and on the verge of mown grass, but Nana would lose some hay. I figured she would have a few words to say to C.C. about that, words he wouldn’t like, and that would force him to apologize, at the very least.

The vehicles pulled up near the trees and killed the engines, pollen and dust swirling around us all. Special Agent Jim Ramsey unfolded himself from Johnny Ray’s pickup, wearing that distinct air of the FBI, suit pants and a heavily starched white dress shirt that glared in the sunlight. We were dating. Sort of. As much as I would let us. Jim was divorced, with a young daughter I hadn’t met yet. I liked Jim a lot, far more than I admitted, but he was nearly nine years younger than I. It was the age difference that I was having trouble with.

The sheriff, Johnny Ray and five cops, some in uniform, followed Ramsey from various vehicles. All were men except for one of the crime-scene techs, and I nodded to Skye McNeely, who waved back, holding up a box of Benadryl. She was my height, plump from motherhood, and newly married to the father of her child. I knew most the other cops from the rescue squad, where I volunteered. “Thanks,” I said, catching the box Skye tossed.

“Ashlee,” Sheriff Gaskins called, swiping an arm over his sweaty forehead. His pale skin gleamed in the bright sun, and sweat already stained the western-style suit coat he removed and tossed into the van. “The crime-scene guys say you did a good job with the shoe. Very thorough. Listen, thanks for getting us this far.”

“Welcome,” I said, watching the cops stack equipment and bags of fast-food breakfast. The smell of bacon and eggs made me salivate.

“That the tracker dog?” Ramsey asked.

I glanced at the animals and found Cheeks standing, straining at his leash, tail wagging. I realized he might know some of the cops, too.

“I know Cheeks,” Gaskins said. “Best tracker in the state at one time. Caught those bank robbers on motorcycles back in ninety-seven. Tracked them twenty miles to their homes.”

“That’s Cheeks. He’s still got a nose, but his hips are going,” I said.

I took two small pink and clear capsules back to my pack and buried them in the center of a Fig Newton. “Here you go, boy.” Cheeks took the treat instantly. Benadryl was an old veterinarian’s trick. It worked to combat all sorts of problems in older dogs and they could take it every day without upsetting their digestion. The dog rubbed his jowls up and down my leg in thanks and I gently smoothed the length of his ears. He sighed in ecstasy, a trail of drool landing on my boot. I’d reek by day’s end.

“Okay, people, we need to spread out, get as much work done as possible until the investigators get back from the bank scene,” Gaskins said behind me. I hid a smile at his officious tone. C. C. Gaskins was the highest elected law enforcement official in the county, but, while a trained investigator, he didn’t usually handle fieldwork. It was very likely that this was his first independent investigation in years. And he had an FBI guy watching.

“We’ll make a grid,” he continued, “and when the rest of the crew get here, we’ll go over it foot by foot until we find the body or rule out its presence.”

“It’s here.” I stood straight and walked back to the group of cops.

“Woman’s intuition is a wonderful thing, Ashlee,” C.C. said, his tone gently patronizing as he spread out a map of the county on the hood of Johnny Ray’s pickup, “but we need more to go on.”

I stood as tall as God had made me and put my hands on my hips. “Woman’s intuition?” I repeated. “I beg your pardon?”

“We need to go about this search in an approved manner until the dogs get here, Ash. That way we don’t mess up the crime scene. Not that we don’t appreciate all the help you’ve been to this point.” He turned his back to me in the sharp silence and concentrated on his map.

“So I can take myself home and knit awhile?” I asked softly. “Maybe bake cookies?”

Skye snickered before she caught herself and the back of C.C.’s neck burned a bright red. Johnny Ray’s eyes grew big and he hitched up his jeans, disappearing behind his truck. Ramsey glanced curiously at me.

I turned into my mother, God help us all. “I don’t think so. You see, C.C., I’ve had a course in the approved method of evidence collection and preservation, so I don’t think I’ll be messing up anyone’s crime scene.” I turned big, innocent eyes to the cops. “But if I were using woman’s intuition, I’d say the body is thatta way—” I pointed “—about a half mile into the woods, the path clearly marked with bright orange paint.”

C.C. shoved his cowboy hat back on his head and turned slowly from his map to me. He wasn’t happy. “I don’t think you’re—”

“Cheeks found the body,” I clarified sweetly. Skye glanced between us, then busied herself at the passenger seat and a big denim bag planted there. The other cops were promptly busy as well. Ramsey crossed his arms over his chest, cocked out a hip and watched me a little too closely for my comfort level, but I was mad. I hadn’t been anyone’s easy-to-dismiss little woman in four years and wasn’t about to start now.

“You took a dog to the body?” C.C. growled.

I smiled with all the force a Southern woman can offer such a simple act. “C.C., how is Erma Jean?” It was a polite way of telling a grown man that you know his mother and if he kept talking like a fool, she’d hear about it sooner than later. “She and my nana are on that county homeless-shelter committee together.”

C.C. cleared his throat and repositioned his cowboy hat yet again. Probably to keep the steam rising off his bald pate from curling the brim. My grandmother was a big contributor to local political campaigns. So was I. He wanted to shout at me, but there were witnesses. After a moment, C.C. said, “Well, I reckon we got ourselves a crime scene, boys and girls. Miz Davenport, would you please be so kind as to guide us in?”

There were a lot of other things I would rather have done than return to the wooded grave, but my hackles were up and I wasn’t about to head home now. “I’d be happy to, Sheriff.”

Raising my voice, I called, “Johnny Ray?” The stable hand lifted his head so only his cowboy hat and his eyes showed above the back of his pickup bed. “I want you to ride Mabel to the barn, see that Elwyn rubs her down with that liniment Nana made up, wraps her legs, and gives her some TLC. You can leave your truck here and when the other cops get to the farm, ride back with them to show them the way. Then drive your truck to the barn and take Cheeks with you.”

“Yes, ma’am, Miz Ash.”

I wasn’t sure Johnny Ray’d remember all that, so just in case he was a long time returning, I took the Tylenol and gave Cheeks the last of the water from my bottle. “Me and my big mouth,” I muttered to the hound. Cheeks rolled his eyes up to me in sympathy. Johnny Ray set the bit back in Mabel’s huge mouth, adjusted bit and bridle, gathered the reins and climbed into the saddle, sending Mabel’s huge hooves into a slow, stationary patter. Mabel didn’t like men, but she tolerated Johnny Ray well enough.

“Effective technique. Exactly who were you channeling just now?”

I closed my eyes hard for a moment and took a deep breath before turning to face Jim. “My mother. Josephine Hamilton Caldwell. She’s a debutante socialite in Charlotte.”

“A what?”

“Well, she’s a socialite who thinks she’s still a deb. Josephine is sixty-something going on sixteen, with a mouth so sweet, candy won’t melt in it.”

“And she’s why you get sugary as rock candy when you’re pissed off?” He was laughing at me, staring down from his nearly six feet in height, brown eyes glinting.

“As a technique for getting my way, it seemed just as effective as grabbing the sheriff by his privates and has fewer side effects than violence. Being Mama has never resulted in a lawsuit or my being arrested. At least, not so far.”

Jim barked with laughter, the sound startling Mabel, who jerked up her head and blew hard. She wasn’t happy about the stable hand being on her back and was looking for a reason to startle or kick. “Be good, Mabel,” I said. The mare flattened her ears and looked around at the human planted on her back, as if pondering how much effort it might take to dislodge him.

“I said, be good.” She rolled her eyes at me and seemed to consider my command. With a grunt, the mare lifted her tail and dropped an aromatic load, seven distinct plops before she moved away, into the sunlight, and headed toward the barn. The cops found it funny, but I knew when I’d been dissed. “Thank you, Mabel,” I muttered. But at least she did as she was told.

“You want to tell me about the land around here?” Jim asked, controlling his laughter admirably as we walked deeper into the shaded wood.

“The better part of valor?” I asked.

“Retreat isn’t a cowardly action. Not when dealing with a woman who can channel her mother.”

I decided I should let that one go and moved with Jim to the first orange paint mark, set waist-high on a poplar. Behind us, the cops shouldered equipment and followed. One cop complained about having to walk when there was a perfectly good four-by-four right there. C.C. handled that one, growling that the deputy needed some exercise and if he didn’t take off a pound or two, he’d be out of a job.

I didn’t know what Jim was asking about, so I decided on a tutorial. “We’re at the edge of Chadwick Farms, heading toward the eighty acres, give or take a few, of Hilldale Hills. The property between the farms is partial wetland, marked by a sandy riverbed left over from the Pleistocene Age, I think. Anyway, the Chadwicks haven’t farmed this area in decades and the Hills acres were left to go fallow for ten years.”

“Why?”

I told Jim that Hoddermier Hilldale had lain fallow himself in a nursing home, the victim of a stroke that had left him in a vegetative state. His son lived in New York and was less than interested in being a farmer. “Hoddy died in early winter,” I said, “about sixteen months ago. The son, Hoddy Jr., came home and leased out most of the acreage to my nana, who bush-hogged it and put it into half a dozen crops. Hoddy Jr.’s in the middle of investing heavily in the house, outbuildings and grounds as part of a bed-and-breakfast-slash-spa he and his gentleman friend think they can make a go of. Why do you want to know?”

Instead of answering, Jim asked, “Any graveyards nearby?”

It wasn’t an idle question. The man who walked beside me had morphed into a cop as I spoke, his face unyielding, warm eyes gone flat.

“Graveyards? I’m not…Wait a minute.” I stopped and turned slowly, looking up the old riverbed and back down, orienting myself. “I wasn’t thinking about where I am, but yes. This land’s been a family farm since the 1700s. The first Chadwick settled here because of the access to creeks and several spring-heads. When the original cabin burned down, the family moved closer to where Nana’s house is now. Somewhere near here are the old foundations and a small family plot. Why?”

Jim glanced back at C.C. and the men nodded fractionally. The cops seemed abruptly tense, as if I had said something important, but I had no idea what part of my soliloquy it might have been. Why would my family plot make them react? I pointed off to the left and jumped over a ditch, leading the crew to the next mark, this one on a low boulder buried in the earth. “What’s up, Jim? Why are you here?” I asked softly.

“The sheriff asked me in on this.”

“And?”

He seemed to consider what he wanted to say. “The red sneaker.”

“You’ve got a missing child, one who was wearing red sneakers?”

“Something like that.”

I figured that was all I was going to get from him so I just pointed to the next marker, but Jim surprised me. “You might remember that Amber Alert in Columbia last September?” When I shook my head no, he went on. “We’ve had four preteen blond girls go missing in Columbia in the last twenty-four months. The girl in September was one of them. Blond. Wearing red sneakers.”

Which explained why the coordinator of the Violent Crime Squad was traipsing through the countryside with mud on his polished black shoes. The air in the shadowed woods grew colder as I again considered what a body buried here might mean. “Why are you looking for a graveyard?”

“We found one of the missing girls in December, buried in a Civil War-era graveyard. So I was just curious,” he said as we rounded the pile of lichen-covered boulders.

“Putting together a profile,” I guessed.

“We’re working on it.” His voice lost inflection. Cop voice, giving away nothing.

“But keeping it out of the media,” I suggested.

“Not so much keeping it out as not sure whether we have a serial thing going here. Other than the general hair coloration and age, the missing girls have nothing in common.”

“I was trying to stay away from the evidence. I didn’t get up close to the burial site so I’m not sure if it’s near the old homestead. I looked one time and backed away. But it may be. And if so, we’ll see a family burial plot, gravestones lying on the ground where they were washed by a big storm before I was born.”

We moved the rest of the way in silence, the birds flitting through the trees as we walked, chasing one another in spring courtship, preparing for nesting time, an occasional squirrel making a leap from tree to tree. A hawk circled overhead in lazy spirals, searching for prey.

Not far beyond the fallen tree, its bark ripped away by lightning, we caught the smell of old death carried on the breeze. It had been bad before, but with the rising heat, the putrid scent had grown fetid and pungent. One of the cops swore, and I had to agree.

4

I stayed behind the two old oaks when we arrived; Jim stood at the edge of the grave site only a few feet away, hands on his hips while cops ran crime-scene tape from tree to tree at the sheriff’s direction. Though the scene was far from pristine, Jim obviously wasn’t going to add tracks or evidence to it until the photos were finished. Skye and Steven, another deputy, set up cameras and began to take digital and 35mm shots. Steven was giant, an African American with a shaved head and biceps as big as my thighs. Well, almost as big as my thighs.

“Ramsey?” Skye said almost instantly. “Headstones. I count three, lying flat.”

“Where?” he demanded.

“With this marker as six, we got one at two o’clock, one between ten and eleven, and a broken stone that looks as if it’s been moved recently at five and eight.”

I looked where she pointed, my gut tightening.

“Got it. Keep your eyes open for any other signs of grave markers,” Jim said. “Ash says this is nearly three hundred years old. A plot like this might have some uncarved markers, too, or some carved stone that’s so old it’s not easily recognizable as a grave marker.”

She nodded and began removing equipment from the cases they had toted in.

After the shots, Skye passed out protective clothing, paper shoes and coats that shed no fibers. Then she handed out gloves, evidence bags, small cans of orange paint, a one-hundred-foot tape measure for marking a grid and string to run from one spot to another, indicating straight lines. Together, working like a precision team, she and Steven measured the circumference and diameter of the space between the trees, marking off specific intervals around the vaguely circular area. They mapped it out on a pad, creating a visual grid to prevent the crime-scene guys from tripping, adding measurements and other indicators. Skye took more photographs while Steven recorded the dimensions into a tape recorder and on a separate spiral pad.

I had seen cops mark a grid on television using spray paint, and in class we had been lectured extensively on the proper way to handle a scene, but I had never seen one detailed in person. It was very clean and geometrical. I noticed that Skye and Steven walked carefully, studying the ground before putting down a bootie-clad foot. They avoided the center of the area, where clothing peeked from the makeshift grave. The alleged makeshift grave.

I knew that, until they saw human remains, it would be only a suspected grave. All this effort and we didn’t even know for certain if there was a body or if it was human. The toe could have come from somewhere else. This grave could be a dog, buried in a pile of rags. Not a child. It could be anything. I wanted it to be anything, anything but a little girl.

All the cops seemed to have a job except the sheriff. Gaskins stood back and looked important. Jim was out in the trees, walking a course around the site in a spiral, marking things on the ground with painted circles. A quiet hour passed during which I found I could disassociate myself from the meaning of the scene and watch. Perhaps that was part of my nursing training, being able to put away normal human feelings and simply do a job. The cops moved in slow, studied precision, touching nothing, recording everything on the detailed evidence map that would be one result of today.

Into the silence that followed I said, “Cheeks buried his face in that strip of cloth right there. There’ll be drool and hair on it. And I think my other two dogs—” I paused, breathless as the meaning of my words slammed into me. I licked lips that felt dry and cracked. “I think they actually dug up the body and rolled in it. You’ll want to take samples from each dog, I’m sure.” The cops were looking at me. I thought I might throw up. I pressed my hand to my stomach. “Johnny Ray has Big Dog and Cherry both locked up in the barn.”

The cops went back to work without a word. Gaskins called in my information to one of the investigators driving in from Ford County and told him to take care of the dog samples before coming out to the site. No one said anything much after that.

The preliminaries over, Jim donned fresh gloves and booties and tossed several evidence bags into a larger bag he marked with black ink. With the digital camera slung over his shoulder on its long back cord, he followed a straight line he referred to as CLEAR. Walking slowly from the two oaks into the center of the small clearing, back hunched, eyes on the ground, he marked evidence as he moved but left each item in place, a paper bag beside it. When he reached the scrap of cloth that Cheeks had drooled on, Jim looked up at me with a question on his face and I nodded. “That’s the one.”

He photographed the scrap of cloth where it lay and took another shot in relation to the total scene. “Document contaminant information,” he said to Steven, “with the year, case number and item.”

“Got it,” Steven said.

Jim marked the photo with the same numbers and continued his slow methodical pace to the center of the circle. Taking several shots, he backed out the same way he’d gone in, and handed the photos and camera off to Skye. “You the acting coroner today, too?”

“I have that pleasure,” she said, her tone belying the words. It was common in poor counties for law-enforcement officers to be trained in several different fields. Skye was a trained crime-scene investigator and also worked as part-time county coroner. She moved closer to the edge of the clearing. “What do we have?”