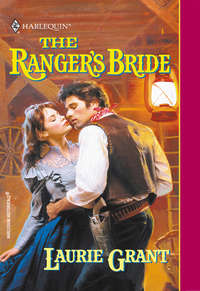

The Ranger's Bride

“Asa…there’s five more people dead out there, about three miles out, where we were attacked. The driver, two women—”

“Women?” someone cried. “They killed women?”

Suddenly feeling more weary than she ever had in her life, she nodded and went on. “Another man who was a drummer, and the sh—” She shut her mouth. She had almost said, “the shotgun guard.” Quickly she corrected herself and told the lie. “And a Ranger.”

“There was a Ranger aboard? They killed a Texas Ranger?”

“Where was the shotgun guard? The stage company usually has a shotgun guard riding up top with the driver.”

“I—I—” Addy stammered. Was her lie to be exposed so easily? She thought fast. “The Ranger was riding up on top…I guess he was acting as the shotgun guard?” Then she thought it would be best to mix in as much truth with her lie as she could. “The stagecoach driver was killed first, and he fell off the top. Then I think the—the Ranger grabbed the reins and tried to fire back at them…but they caught up and then the man…inside there—” she shuddered as she gestured at the interior of the coach “—was shot and fell over on me. I guess I must have fainted, for when I awoke and managed to get out from under…the body—” she closed her eyes, and her shudder was not the least put-on “—I found everyone else lying dead outside the coach.”

“Sweet heaven,” someone muttered.

“Sounds like the Fogarty Gang,” someone else said.

“Didja see their faces, Miss Addy? Any of them buzzards?” someone else asked.

Addy shook her head. “Not really,” she said, though the image of a face half-concealed by a red bandanna as he stuck a pistol in the window flashed through her brain.

She shut her eyes again, suddenly feeling more than a little dizzy. She swayed.

“Miss Addy, didja—”

“Shut up! Can’t you see she’s about to swoon?” snapped Asa. “Back away, gentlemen, back away. I’m gonna take Miss Addy inside so she can sit down where it’s cooler.” Asa Wilson inserted an arm bracingly around her and guided her firmly but gently toward the door of the jail. “You men, stick around,” he called over his shoulder. “We’re going to have to form a posse—and if someone can drive a buckboard out there, those bodies have to be brought in for identification and proper burial. Oh, and Miss Morgan, would you have any smelling salts with you?”

“Oh, dear me, no,” Addy heard Beatrice Morgan say. “But I could run back to my house….”

Beatrice Morgan was a plump old maid of perhaps sixty years who had already come to Addy once for the making of a new black bombazine dress. Black was all she seemed to wear, though who she was in mourning for was a mystery to Addy and the rest of the town.

“No smelling salts, Asa,” Addy protested. The stinging scent of hartshorn always nauseated her.

“Never mind, Miss Morgan, perhaps it would be more helpful if you’d come in and be with Miss Addy,” Asa said. “A feminine presence, you know…just Miss Morgan,” he said, as a handful of Connor’s Crossing ladies moved to follow them. He pushed open the door and ushered Addy and Beatrice Morgan inside.

It felt good to sink into Asa’s big chair while he bustled about, pouring Addy a drink of cold water from the pitcher he always kept on his desk. The cool dimness of the jail office was restorative, too, after the heat of a Texas summer afternoon.

“Here, my dear, let’s elevate your feet on this,” Beatrice said, lifting Addy’s feet and shoving a stack of unread newspapers underneath them. “Addy,” she whispered, “surely we had better loosen your stays, too? Sheriff,” she called in a coy voice, “would you please step out while I…ahem!…assist Miss Addy to breathe better?”

Addy had no need for tight-lacing and had had about enough of Miss Morgan’s fluttering, well-intentioned though it was. She opened her eyes. “Never mind, Miss Beatrice, I’m breathing just fine, truly I am,” she said with as much firmness as she could muster.

Beatrice Morgan looked disappointed. “Well, if you’re sure, dear.”

Asa Wilson cleared his throat. “Well, Miss Addy, I’ll be leaving for a little while anyway. I’ve got to go out there now and organize a posse. I won’t be gone any longer than it takes to capture those no-good bas—Pardon me, ladies, those outlaws,” he amended. “In the meantime, Miss Morgan can stay with you here. And then I’ll take you home in my buggy.”

Addy knew there wasn’t a chance in a million that the outlaws would still be in the area, but she didn’t want to deflate his pride by arguing with him. She couldn’t stay here, though, not with the wounded Ranger awaiting her return!

“But it could take you hours to find their trail and capture the outlaws, and then you’ll be much too busy guarding them to be worrying about me, Asa—though I thank you for your concern, of course. I’m feeling much better, truly I am,” she insisted. “Let me just sit here for a few minutes, and then I’ll just walk on home—”

“You’ll do no such thing,” Beatrice said, clucking disapprovingly. “It’s out of the question for you to be alone tonight. After your grueling ordeal, you need the company of another woman. You’ll come to my house and stay the night. You’ll have a hot bath while I wash the bloodstains out of that dress, and you can wear an old wrapper of mine while it dries.”

“I’m much obliged, Miss Morgan,” Asa said, looking relieved as he strode to the door. “Miss Addy, you do just what she says. I’ll call on you there in the morning.”

If it hadn’t been for the presence of Rede Smith at her house, Addy would have been tempted to allow Beatrice to take her to her home and fuss over her. Addy had already been invited for supper twice and knew that Beatrice Morgan was a legendary cook, and she was sure she would feel much better for a bit of the kindly older woman’s pampering. But she had to get home to the Ranger. Every minute she delayed increased the Ranger’s chance of developing fatal blood poisoning.

“But I’m afraid I can’t—”

The sheriff let the door slam shut behind him, a man on a mission of justice.

“Miss Beatrice, I appreciate your kindness,” Addy began, “truly I do, but I’m fine. I’ll just walk on home. I have so much to do—”

“Addy Kelly, all that stitching can wait. You’ve had a dreadful shock. Walking on home by yourself, indeed! You wouldn’t make it five yards beyond the barber shop! If you won’t come to my house, I’m coming to yours!”

Oh, dear, now she had truly made things worse. She could just picture Beatrice Morgan discovering the wounded man in her bedroom!

She could see there was no use arguing with the determined spinster. But the excitement appeared to have taken a toll on the old woman, for she looked suddenly fatigued. That gave Addy an idea.

“Miss Beatrice, I suppose you’re right,” she said meekly. “I shouldn’t think of going home right now. In fact, I’m suddenly so tired I can’t even move beyond this jail. I think I’ll just go lie down in there for a few minutes,” she said, pointing to the cot in one of the jail’s two cells. As soon as I’ve rested, we’ll walk down to your house, all right?” She wasn’t worried about using the same cot on which lawbreakers slept. The cells rarely had occupants, and Asa was so fastidious that the whole town teased him about having the sheets laundered after a cell had been occupied.

“Now you’re sounding more sensible!” Miss Beatrice crowed triumphantly. “You do just that! I’ll sit right here and wait. Don’t you get up a single moment before you’re ready.”

As soon as Addy rose and moved toward the cell on the right, she plopped herself down in the same chair Addy had been sitting in. Already, the plump older woman’s eyelids were sagging over her watery, pale eyes. “I’ll be right here, dear,” the older woman murmured.

Addy made a great show of settling herself down on the narrow cot, yawning elaborately while she said, “I declare, I’m suddenly so tired…don’t let me fall asleep, Miss Beatrice….”

Beatrice Morgan’s eyes had already drifted shut.

Addy lay on the cot in the jail cell, listening to the horses’ snorting and stamping of hooves, the creak of leather and the jingling of spurs and bits as the men of Connor’s Crossing prepared to ride in pursuit of the Fogarty Gang.

It took about half an hour, but finally they were ready and Addy heard Asa Wilson call, “All right, men, looks like we’re ready to move out. Sooner we hit the trail, the sooner we catch those no-account bastards and bring them to trial. Now, there’ll be no talk of lynching, is that clear?”

Dear Asa, Addy thought. As upright and steadfast as the day was long. He truly believed that he and his little Connor’s Crossing posse were going to come upon the outlaws, milling around out there among the hills, just waiting to be caught.

Asa was a good man, and Addy was fond of him, and even fonder of his little boy Billy. Billy’s mama had died two years ago during a cholera epidemic, and Addy knew Asa wanted to give the boy a mother again. And so Asa had decided he was in love with Addy, and perhaps he really was. But Addy knew she didn’t love Asa, and probably never would, and that her assumed widowhood functioned as a sort of shield from his ready devotion. She realized that when the year was up since her husband’s supposed “death” she was going to have to either accept the proposal of marriage Asa would undoubtedly offer, or admit that she didn’t love him.

She also knew that all it would take to discourage Asa Wilson was the truth—that she was a divorced woman, not a widow. Shock would widen those clear blue eyes, and then he would look sad. He would say he understood, and of course he would not trouble her with his attentions again. And he would never tell anyone in town that she had deceived them all in order to retain their goodwill, and that she was no honest widow, but a woman who was beyond the pale of respectability—who had actually divorced her husband.

Addy couldn’t tell him, or anyone, the truth. No one must know that her former husband still lived back in St. Louis—assuming, of course, he had not fallen afoul of some liquored-up gambler who caught him cheating at cards.

All sound had died away outside. Carefully, moving slowly to minimize the rustling of the straw-stuffed mattress beneath her, she sat up and then tiptoed to the shuttered window.

By the desk, Beatrice Morgan snored, her mouth slackly open, her head sagging on her thick neck.

The shutter creaked on its hinges as she pulled it open, and Addy froze, but the old woman did not awaken.

Cautiously, she peered out.

The streets were deserted for as far as she could see in either direction. The stagecoach had been moved down the street and parked in front of the undertaker’s shop, no doubt to make removal of the big man’s body easier. Someone had unhitched the four horses that had pulled it. She couldn’t see the livery from here, but she was sure the horses had been put into the corral with hay and water and would remain there until the stage company claimed them.

She had to leave Asa a note, or he’d worry, and perhaps come looking for her at her house. She’d better include Miss Beatrice too, who would be distraught when she woke to find her gone. Careful not to make a noise that would wake the still-snoring woman, Addy grabbed a wanted notice lying on the desk and a stub of a pencil, turned the stiff paper over, and wrote:

Dear Asa and Miss Beatrice,

Thank you for your kindness. I’ve gone on home, as I’m sure I’ll be more comfortable in my own place. I’m going to go to bed as soon as I get there. I’ll be fine, don’t worry. I’ll see you both tomorrow.

Gratefully,

Addy Kelly

Then she tiptoed to the back door and stealthily lifted up the latch and let herself out. So that no one would see her, she would go down the back street, which connected up with the main road at the edge of town. Once she crossed the bridge over the rocky-bedded Llano, it was just a short walk to her house.

Chapter Five

The house was quiet—much too quiet—when Addy entered it. Dear Lord, had his wound somehow started bleeding again? Had Rede Smith bled to death?

The thought pierced her with guilt for having left him, even at his direction and for so brief a time. Addy hurried down the hall and through the kitchen to the back bedroom.

“Judas priest, woman, where have you been?”

Rede Smith was sitting up in bed, propped up by her two feather pillows, his color pale but no paler than when she had left him.

She let out the breath she’d unconsciously been holding.

“It took considerable cunning to escape a woman like Miss Beatrice Morgan, I’ll have you know,” she informed Rede tartly, and then explained how the sheriff and the old woman, determined to coddle her after her ordeal, had conspired to keep her in town.

He frowned as she described Asa Wilson’s concern for her.

“Don’t worry,” she said, assuming he was just worrying about the bandits’ trail getting cold, “he didn’t remain any longer than he had to, once he’d gotten the facts and seen to my welfare. He’s already out there with a posse, looking for the Fogartys. It was the Fogarty Gang, you think?”

He gave her a baleful look. “I don’t think, I’m sure of it,” he said. “You didn’t tell him about me, did you?”

She was already exhausted from the day’s events, and his scornful tone sparked her ire. “No, I most certainly did not, though it felt despicable to be lying to that good man, not to mention the whole town—telling him the Ranger was dead, when you’re lying right here in my bed!”

She felt herself blushing at what she had said, and hoped he hadn’t noticed, but of course the Ranger missed nothing.

He scowled. “What’s the matter, is the virtuous Widow Kelly the sheriff’s secret sweetheart? Are you afraid he’ll find me here and think he has a rival?”

Her temper reached the flashpoint and ignited.

Hand raised to slap his face, Addy took one step toward the bed before she realized what she was about to do and stopped dead in her tracks.

Addy saw in his eyes that he fully realized her intention, and wanted to die of shame. She took a deep shaky breath. “I won’t do it. I won’t slap a wounded man, though you richly deserve it after what you just said.”

He looked away first, scowling again. “I’m sorry. It’s none of my business who visits your bed, Mrs. Kelly,” he said stiffly.

“No one—” she started to say, and then stopped herself. He was right. It was none of his business. Let Rede Smith think Asa Wilson was her lover, if it would keep him from behaving improperly toward her. He didn’t have to know Asa was the last man who’d make an ungentlemanly move toward a woman he thought was a six-month widow and whom he considered a lady. But if she expected meekness out of Rede Smith now, she was doomed to disappointment.

“Are you a good liar?” he demanded. “Did they believe you?”

“I think so,” she said, striving for a level tone. Oh, you don’t know how good a liar I am, Rede Smith. I’ve been living a lie ever since I came to Connor’s Crossing.

“All right, good. I need you to get this bullet out, now that you’re back. And I’ll take that whiskey now, if you don’t mind,” he added.

Addy bristled anew at his brisk tone, and again when she had brought in the bottle and a freshly washed glass, only to hear him say, “I need you to boil whatever knife you’re going to use for several minutes.”

She started to bark back a sarcastic reply, then saw the apprehension that lurked within his dark gaze. Rede Smith was worried about how he’d react to the pain of having that bullet removed. The realization rendered him more human and made her stifle her stinging retort.

“Certainly.” She turned on her heel and left the room.

It took her half an hour to get ready. She had to light a fire in the stove, pump a kettle full of water, set it to boiling, and after selecting a knife she normally used for paring fruit, boil it for several minutes. While she waited she washed her hands thoroughly, using the lye soap she used on laundry days.

By the time she returned to her bedroom, carrying the kettle with the aid of two clean cloths, the whiskey had apparently mellowed his mood.

“Will this do, do you think?” she said, holding the kettle so he could see the paring knife in the still-bubbling water.

He darted a glance at it in the steaming water, then quickly back at her. “I guesh sho—so,” he said, his exhaled breath sending a cloud of whiskey fumes in her direction.

He was apparently aware that some of his words were slurred. “Shorry—I mean, sorry I was so gr-grouchy, Miz Addy. I r-reckon I’m not lookin’ forward to this little bullet-huntin’ exspedition we’re ’bout to go on.”

His face was flushed, his dark eyes dulled. She glanced at the liquor bottle, and saw that he’d drunk over half the contents of the bottle, which had been nearly full. Heavens! It was amazing he was still conscious, let alone talking.

“I can understand that,” she said.

He sighed, and said in a resigned tone, “Well, le’sh get thish over with, then,” he said, and sank back in the bed. “D’you have anyshing—thing I can bite into?”

She stepped over to her chest of drawers, pulled out one of her handkerchiefs and rolled it up, but when she stepped back to the bedside, his eyes were closed and he was breathing deeply and evenly. She hoped he was unconscious from the prodigious amount of whiskey he’d drunk so fast, and that he wouldn’t come to until she was done.

She reached inside the pocket of the apron she wore and brought out the lump of lye soap. Dipping one of the clean cloths with which she had carried the hot kettle into the hot water, she rubbed it over the lump of soap until the cloth was soapy. Then she used it to cleanse the remaining dried blood from around the wound’s edges. He winced slightly when she rubbed hard at a stubborn clot, but otherwise did not stir.

Once she had cleansed a wide circle of skin around the raw red edges of the arm wound—making it ooze a trickle of blood, she noted—she touched the flesh gingerly, feeling for the spent bullet within.

For a moment she could feel nothing, but then she closed her eyes and palpated his upper arm again, using just the ball of her index finger, exploring a widening circle around the arm. Finally she found it—a hard lump about half an inch beneath the surface of the back of his arm. She sighed in relief that she would not have to probe blindly with her makeshift scalpel. But the wound was awkwardly situated. How was she to get to it without standing on her head?

After a moment, she tucked Rede’s hand, palm up, under his head, which exposed the posterior of his upper arm perfectly. Movement of the wounded arm made him flinch and mutter something unintelligible, but once she let go of the arm, he seemed to sink back into insensibility.

She turned to retrieve the knife.

But the water was still too hot to dip her hand into. Crossing the room, she raised the windowsill and dumped most of the water onto her kitchen garden below. A couple of radish plants might never be the same, she thought, but it couldn’t be helped.

Now she could reach the knife. Using the other clean cloth to pick up the still-hot handle, she moved back to the bedside, her insides churning within her.

Gently bred ladies did not do such things. Extracting a bullet was a job for a doctor, or at least a tough frontier woman, not Adelaide Kelly of the St. Louis Kellys.

But he didn’t want her to call a doctor or anyone else. He believed it was important for his presence here to remain a secret. If the bullet was not removed he might very well develop gangrene and die. So it was up to her.

Uttering a prayer that God would help her do this without causing him too much pain, she bent to her work.

Her first tentative slice into his skin brought him yelping up off the bed, both fists clenched. “Whaddya think you’re do—”

She sprang back, but before she could say anything, his bloodshot gaze focused on her and he muttered, “Oh. ’S you, Miz Kelly. I…’member. G’wan, finish it.”

She darted close and threw him—much as one would throw a hunk of meat at a vicious dog—the handkerchief she’d gotten out for him to bite. He thrust the rolled square in between his jaws, closed his eyes, and replaced the hand of his wounded arm underneath his head. He gestured with his other hand that she was to go ahead, then grabbed hold of the bedpost. Gritting her teeth and holding back the sob that threatened to choke her, she did just that.

Five minutes later, drenched in perspiration, she straightened, her bloodstained fingers clutching the bloody, misshapen slug.

“I got it, Rede,” she said softly. “It’s out.”

He opened bleary eyes and sagged in the bed, letting out a long gusty breath.

“Quick, pour the rest o’ that whiskey over my arm,” he growled, closing his eyes and setting his jaw. He flinched as she obeyed, but made no sound.

She had done it. The room spun, and she leaned on the bed for support. Then she felt his hand on her wrist.

“You did real fine, Miz Kelly,” he said. “Thanks. Now maybe you better sit down. Oh, an’ you might oughta open up s’ more whishkey. You’re lookin’ a mite pale.”

Rede lay in Adelaide Kelly’s bed, hearing her rooster crow and watching dawn gradually light the square of glass opposite his bed. The ache in his arm—and the matching throb in his head due to the whiskey he’d drunk the evening before—had awakened him an hour ago.

He’d been a fool to think that he could steal back into the area by taking the stage. He should have just taken his chances riding in—traveling under cover of darkness, perhaps, and making cold camps in gullies. Now, because someone had had loose lips, five innocent people were dead. And the sixth had had to dig a bullet out of him and was going to have to play hostess while he laid low here and recovered.

The whiskey had made his memories of last night fuzzy around the edges, but he remembered enough that he could still picture her bending over him, her pale, sweat-pearled brow furrowed in concentration as she clutched the paring knife that had eventually rooted the bullet out of his flesh.

She’d done a hell of a job, he thought, for a refined lady who’d obviously never planned on performing surgery. Captain McDonald couldn’t have done any better, and he sure as hell wouldn’t have bothered apologizing up and down for each and every twist and turn of the knife, as Addy Kelly had done. Yessir, she had grit, Addy Kelly did.

But she did do one thing better than his captain: snore. He’d camped out plenty with the Rangers’ commander when they’d been in pursuit of outlaws or marauding Indians, so he should know, and Addy Kelly could outsnore all of his company any night of the week.

Possibly it was the uncomfortable position she had slept in, Rede thought, eyeing her sympathetically. She hadn’t left the room but had passed the night in the chair next to the bed. She was there still, her head resting against the wall, her hands clasped together in a ladylike primness that was entirely at odds with the buzzing noise coming at frequent intervals from her mouth.

Sometime during the night she’d left him long enough to wash up and change out of her bloodstained dress and into a violet-sprigged wrapper. She’d let her hair down and braided it, and now the thick chestnut plait hung over the curve of her breast.

All at once she gave a particularly rattling snore. It must have awakened her because she blinked a couple of times, then shut her eyes again and still sitting, breathed deeply, stretching long and luxuriously.

The action stretched the flowered cotton across her breasts, and he luxuriated in the sight. Lord, but he loved the shape of a woman not wearing a corset.

Something—perhaps the groan of pleasure he had not succeeded in altogether smothering—must have alerted her she was not alone, for Addy’s eyes flew open and she caught sight of him watching her.

She uttered a shriek and jumped to her feet.

“Whoa, easy, Miss Addy,” he murmured, and put out a hand in an attempt to soothe her. He tried to relieve her embarrassment by making a joke. “I don’t look that frightenin’, do I?”