Predator Of Souls

Alessandro Norsa

PREDATOR OF SOULS

Journey in the land of the vampires

Compiled by signor Alessandro Norsa and accompagned on location by most highly praised advisors

Original title: Il ritorno del non morto. Viaggio nel regno dei vampiri

Translation: Peter Fogg

TEKTIME 2017

Thanks for the kind cooperation from:

Prof. Rudolf M. Dinu, Direttore Istituto Romeno di Cultura e Ricerca Umanistica â Venezia [Director of the Romanian Institute of Culture and Humanities Research â Venice]

Dr Mihai Stan, Istituto Romeno di Cultura e Ricerca Umanistica â Venezia [Romanian Institute of Culture and Humanities Research â Venice]

Prof. Tudor SÄlÄgean, Direttore Muzeul Etnografic al Transilvanei â Cluj-Napoca (Romania) [Director of the Ethnographic Museum at Cluj-Napoca (Romania)]

Prof. Ion ToÅa, Historian at the Muzeul Etnografic Transilvanei â Cluj-Napoca (Romania) [Transylvanian Ethnographic Museum at Cluj-Napoca (Romania)]

Prof. Alberto Borghini, Direttore Centro di Documentazione della Tradizione Orale [Director of the Oral Tradition Documentation Centre] Piazza al Serchio (CTDO) engaged in the construction of a national folklore archive and Professor of Cultural Anthropology, Polytechnic University â Turin

The Romanian advisers: Mocan Lena Zamfira (Zalau â Salaj), Florea Cosmi (Runcu Salvei) and Pivasu Lucia (BraÅov).

Particular thanks go to my friends Aldo Ridolfi, who, with the greatest patience and painstaking thoroughness helped to edit the text, Gigi Speri, who with shrewd graphics expertise gave form to the book and Simona Strugar, valuable contributor, to whom goes all my gratitude for the translation of the Romanian texts and for having given me the possibility to get to know and appreciate the culture of her country, as well as providing me with valuable suggestions on reading about the myths of Transylvania.

Original title: Alessandro Norsa: Il ritorno del non morto.

Viaggio nel Regno dei Vampiri. Liberamente: March 2016 ©. English version: The predator of souls. Journey in the land of the vampires, March 2017 ©.

https://www.facebook.com/Il-ritorno-del-non-morto-218253505241025/

e-mail: norsaalessandro@yahoo.it Publisher: Tektime â www.traduzionelibri.it Translation: Peter Fogg All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, including by any mechanical or electronic system, without the written permission of the editor, except for brief passages taken for the purposes of review.

Edizioni LiberAmente [Editions]

Psychology and Anthropology Series

- Alessandro Norsa. Nellâantro della strega [In the witchesâ cave]. La magia in Italia tra racconti popolari e ricerca etnografica [Magic in Italy from popular stories to ethnographic research]. 2015

- Alessandro Norsa. Nel sabba delle streghe sotto il Noce di Benevento [In the witchesâ Sabbath under the walnut tree of Benevento]. 2016

- Alessandro Norsa. Il predatore di anime [The predator of souls]. Viaggio nella terra dei vampiri [Journey in the land of the vampires]. 2016

Fiction and Poetry Series

- Aldo Ridolfi. Novelle e racconti [Short stories and tales]. 2015

- Simona Strugar. Solstizio [24th June]. 2016

PREFACE

This brief but rich - and interesting - work by Alessandro Norsa, which is about vampirism and what we can call its âsurroundingsâ, also makes use of some interviews made by the Author himself in Romania.

For our part, we limit ourselves to emphasise certain points. The first, among those we wish to recall, regards the practice of covering up mirrors on the occasion of a death:

On the death of a family member the mirrors in the house are covered because otherwise the soul, being reflected, remains imprisoned between the walls of the house,

The old lady Florea tells us. Thus, in turn, the youngest Lena says:

(...) the mirrors and any other reflective surface are covered to avoid the spirit (i.e. of the dead person) remaining a prisoner in the house.

Beyond the euphemistic âexplanationâ (the soul of the dead would remain âimprisonedâ inside the house), we are confronted - it seems to me fair to support) - by one of the practices of âexpellingâ the deceased from the domestic space.

And, naturally, we are confronted by the basic themes of the reflected image.

It is relevant, along an âanalogousâ line, what Lucia (about 50 years old), from the area of BraÅov, refers to when she tells us inter alia:

At midnight... I donât know at what time of the year... Perhaps when a person has died...â I switched off the lights, looked in the mirror and saw the vampire in the mirror... Meaning that the dead person had not been happy in their life...

Therefore, cover the mirror when someone dies so that the dead person is not reflected... if they are reflected it would be a vampire...

And she added:

(...) The vampire would be the spirit of the dead person when he or she was not happy in their life... when a dead person is not happy it is very bad...

Previously she had said:

When someone dies, a husband, brother, sister, someone in the family... a baby... it is customary to cover the mirrors with a dark cloth and to light the candles.... you cover the mirrors because they say that it brings bad luck... if you donât cover the mirrors, the dead person is reflected in the mirror - for three days the spirit remains in the house - it goes out and remains near the house for forty days and after forty days it disappears - it goes away into its own world...

It would seem to be understood that if you do not cover the mirrors the dead person who was not happy in life, being reflected, remains in the house as a vampire - as a vampire reflection - and âthat is very badâ. The fear, essentially, is of the vampire-reflection - and that this vampire-reflection (âif it is reflected it would be the vampireâ) remains in the house; etc. Hence the ânecessityâ - it is revealed - to cover the mirrors in an event of a death so that the spirit of the dead person does not remain âa prisoner in the houseâ (a âeuphemistic imageâ). Coming back to Lena, the woman tells also of a girl who was transformed into a toad by the effect of a spell the girl requested from the witch herself. Here is what happened:

(...) my mother told me about an engagement opposed by the boyâs mother. The girl went to a witch who put a spell on her. Every night the girl changed into a toad to enter her fiancéâs house. The boyâs mother, often finding that big, croaking and squirming animal under her feet, wanted to kill it, and, one day, achieved her intention. In that moment, the boy died (...).

It is a matter here of a narrative outline - of an âeventualityâ that one encounters frequently also in Italian folklore: a witch changes herself into an animal or an object, which it then hit, and the witch ends up, therefore, maimed in a âcorrespondingâ part of her body. Just because it has to do with a transformation into a toad, I report that this attestation comes from Garfagnana (Cogna), in the province of Lucca [Central Italy]:

A young man from Villa Collemandina was returning home after having been at his fiancéeâs. It was the middle of the night, and to see he had a torch made of straw. At a certain point, he stumbled on something soft; he stopped, and in the faint light of the flame saw a large toad; annoyed, he thrust the torch towards the poor animal and gave it a good scorching. The next day he met a friend, whose face was disfigured by a horrible wound. âWhatâs happened to you?â - he asked him - âAh!, after having ruined me in this way you also ask me what happened to me?!â - âBut what are you saying?â Could it have been me that burned you?â - âYes, it was really you, last night! That toad that you met, it was really meâ.

Consider, moreover, as an example, the following tale, heard in Piedmont, relating to the connection between âbramblesâ and witch (masca):

There was between Castiglion Tinella and Valdivilla nearby on a bend a short-cut called âthe goatâs short-cutâ. And it was near this short-cut that everyone who passed by saw the masks. On this road, there were always some brambles which blocked the road. One day someone says: âI want to see properlyâ. Take this scythe and cut it downâ. Having reached the place, he hits him and suddenly hears someone say: âHit him againâ But the man did not hit him a second time. At a later stage, they learned that there was someone with his arm torn off.

On the bramble hit by the scythe, it is obvious that the arm cut off by the masca âmatchesâ. Another point that I intend to touch upon is that relating to âconviction that girls with blue eyes have the power to put the âevil eyeâ on someone, without - âsometimesâ - âdoing it on purposeâ (and itâs still Lena talking). However, regardless of other types of âexplanationâ, I would not rule out the fact that also in this case we are faced with an emergence of the colour, light blue/blue/deep blue, inasmuch as the colour of the negative.

Dealing now with the account of Alessandro Norsa, the Author highlights how the negative beings assembled âcircling around in the airâ (p. ex 9) For my part, I would take this opportunity to underline how the âcircle/curve/spiralâ element may be considered as a characteristic of such a being (and we have seen how the âcurveâ intervenes in the Piedmont attestation (referred to above). As far as concerns - finally - the practice of placing a spindle on the tomb of the deceased (Norsa, p. ex 10), I would not be out of place in recalling the tale, which one comes across widely, at least in Italian folklore, relating to the woman who, for a bet, goes into the cemetery at night, carrying out the gesture, in fact, to place a fuse on the tomb.

For the rest, it would perhaps be right to assume that also on the basis of accounts relating to the âfuse betâ - so to speak - an analogous meaning: an analogous âbasic valueâ remains valid, at least at that time.

Alberto Borghini, 14.03.2015

TO THE GRACIOUS READER

Who of you has not heard talk of Dracula and the vampires? These names are so popular as to become part of our common cultural heritage. For three hundred years, in fact, at least once in a century the world is completely prey to a vampire fashion: in the first half of the sixteenth century it was the time of the so-called âvampire plagueâ, towards the end of the nineteenth century / the beginning of the twentieth century the novel Dracula by Bram Stoker reawakened interest and even today (in the feast of Halloween and the television saga Twilight) we see a new wave of interest. The books already written follow roughly the same script with very few variations. Notwithstanding the mention initially made, the sense of this book, as already widely explored by other authors, is not that of dwelling on the famous Stoker novel, nor even going into the making of the horror film. We will try instead to understand the origin of the story between the leaves of the ancient myths, above all those coming from Romania and the Balkans, because it is from there that the image of the vampire that we all have in mind is formed. To enter further into the matter we have started our research with the reading of old Romanian texts on ethnography and mythology, to then go directly to Transylvania among the villages and the people, searching for directions in the traces of Dracula. It is therefore a journey into the past to understand where the image and the characteristics were born of the vampire, which is well-known to us, as well as to learn about the place from which it originates.

INTRODUCTION: OR, RATHER, WHERE THE INTENTION OF THE STUDY IS EXPLAINED

Let us close our eyes for a moment and try to imagine ourselves as Dracula. How do we imagine him? Probably tall, old and dressed in black. The aquiline face, the thin nose with a pronounced bump and strangely arched nostrils. The noble and wide forehead, the hair shaved at the temples, but full on top. The eyebrows thick - they almost join up over the nose. The mouth, for what emerges under the moustache, is stiff and with an almost cruel profile. The teeth, white and strangely pointed, emerge from the lips, whose bright colour reveals an amazing vitality for a man of his age. The ears are pale, and pointed; the chin wide and strong, the cheeks firm, even though hollowed. The whole face is suffused by an incredible pallor.

This is the sinister figure of Dracula which, in a detailed and incisive manner, is described by Stoker in his novel. Like an expert folklore student, Stoker merges into one personage mythological figures from various traditions: above all those relating to the Irish folklore heritage mixed with myths and legends from other countries, particularly from Romania. For example, the characteristics of the particular eyebrows just observed we find again in some disturbing mythological figures from Eastern Europe, as we shall see, while the pallor is typical of the wandering ghosts, the souls of the dead. But let us turn again to the novel to touch on other elements that can be useful to us. Dracula is noble. He has fascinating manners and speaks various languages. But he does not have servants, he does not go to worldly receptions, he does not indulge in the earthly pleasures of good food or beautiful women. He has magic abilities and knows the language of animals so well that he can command them. He has the icy skin of the dead, his image does not reflect in the mirror, he possesses enormous physical strength and incredible speed of movement, he can hypnotise you with his stare, transform himself into a dog, a wolf or a bat. He sleeps during the day and at that time he looks dead, even if he is concious of what is happening around him. But why have these become the coordinates on which we orientate our knowledge of Dracula? Essentially you need the creative genius of the famous Irish novelist who, in an astute way, to greater convince the reader, made the presence of Dracula realistic, associating it with a personage really identifiable in history: the ferocious Wallachian Voivoda Vlad III who lived from 1431 to 1476, son of Vlad II called Dracul. This chief ruthless enemy of the Turks, inheriting his nickname from his father and became known also as Dracula, a name that in Romanian means the devil, the suffix âulâ corresponds to the definite article, which, in that language, is put at the end of the word.

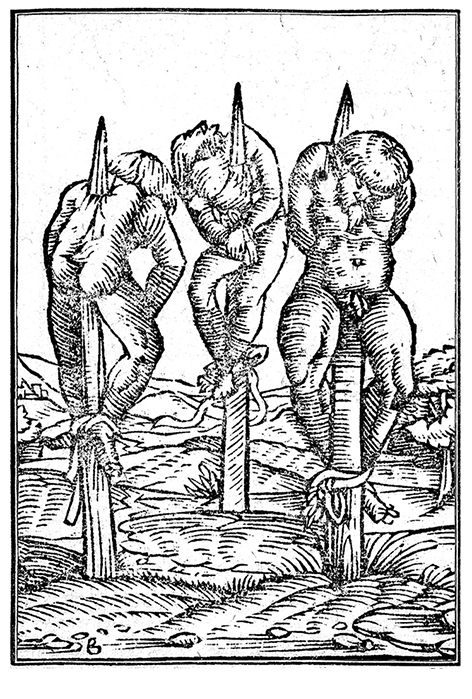

It should be underlined that from a historical point of view Vlad III, also called Tepes (Å£eapa in Romanian means stake or pole), has never been associated with vampirism. There were however some coincidences that could have effectively lead to the comparison with that Romanian prince so present in Eighteenth century European literature. The reason for such notoriety resides in some customs that resemble vampires. Above all the method of execution that Vlad III preferred was impalement, which is the practice considered most suitable to destroy vampires. Other convictions, instead, regard its gory operation. Vlad III was in fact likened to those men who were marked by particular wickedness and who, after their death, were said to have transformed into vampires. Tepes, in the end, was decapitated as was done to those who were accused of vampirism and, after the burial, his tomb was opened and looted, which makes one think about the lengths to which the local population would resort. In the course of reading the book we find again these convictions associated with particular exorcist practices developed in an authentic vampire culture which has continued over the centuries.

THE MANY VAMPIRE ROOTS ALL OVER EUROPE, IN PARTICULAR IN THE BALKAN COUNTRIES

The legendary and mythological tradition of vampires, disturbing figures, is rich: beyond the Greek and Roman worlds which have conditioned all western culture, they are present also in Arab, Indian, Chinese and Japanese legends.

In some traditions handed down over time, the vampire is a dead person in flesh and bones who appears to the living in his body and feeds on their blood; in other legends vampires are also the mythological and fiendish spirits that attack the living - and sometimes eat them, or feed on their blood - but that have never been human. In the first case, we will have, for example, that which for Greeks and Romans was called strix (from which the Italian term âstregaâ [witch in English] is derived) which was not a human person, but a nocturnal demon which came out of the tomb, and was feared because considered capable of attacking babies and feeding on their blood. In the second case, the vampire was a dead human person, a living thing that drank blood, it was a particularly malevolent and blood-thirsty witch. In the third case, vampires are dead human beings who appear in their bodies, which assume a physical and tangible reality and are not a simple image or illusion. It is the image that we have of the classic vampire that comes out of the tomb in its body and which you can not only see, but also touch: or rather, it is very resistant and must be destroyed with drastic measures. We maintain that it is not possible to understand the true nature of this being if we do not fall into that type of thinking âof the originsâ that characterised men in the Neolithic period: a world where everything was pervaded by the divine: places, objects, animals, food, rivers, trees and lightning. The divine, under this logic, was not found in an unattainable sky, but here on earth, the place of burial and therefore the home of our ancestors who become in their turn divinities. Starting from these assumptions, there was research for a dimension in which to find an explanation for calamitous events otherwise inexplicable. In an animist logic, therefore, the weakness of the body, not being able to be understood by the medical knowledge which we have today, became the effect of fearful malevolent beings, but not only, they could be the effects also of nightmares, the death of foetuses, convulsions, hysterical crises, depression, distrust, illnesses, pains all over the body, death by suffocation and above all chest tightness with sensations of lack of breath. To be able to carry out so many wicked deeds these entities possessed enormous physical strength and incredible speed of movement, they could hypnotise with their stare and transform themselves into disturbing animals. We will see later the various elements making up the image of vampires which has been traditionally handed down, just like it has been consolidated in nineteenth century literature and in cinema, retracing the origins among the folds of the popular myths and legends. Starting from a reading of the legendary Romanian figures that can be associated with vampires, we will extend our investigation to analogous entities that are found in Eastern Europe. We will then analyse the origins of the myth of Dracula in the myths and symbolic aspects of the animist culture, studying in depth, therefore, the theme of the capacity to transform oneself into a bat and to fly during the night, of the proofs of meetings with the vampire, seducer of young girls, and, finally, of exorcisms as we will see better in the paragraph dedicated to these aspects.

OF THE ORIGIN OF VAMPIRES IN THE MYSTERIOUS LAND OF ROMANIA WITHOUT IGNORING OTHER IMPORTANT ANALOGIES

The myth of Dracula was born from the union of various Romanian myths and legends. What do they call vampires in Transylvania? The Australian ethnographer, Agnes Murgoci, documented in Transylvania various types of blood-suckers, like, for example, the ÅiÅcoi (known elsewhere by the name Moroi) and the Vârcolaci (Svârcolaci) and Pricolici called Vrykolakas in Greece. So many different names to describe figures that assume, on the whole, similar characteristics, indicating deteriorating, damaging or deadly action. We will therefore start our voyage in the realm of the vampires through reading the Romanian literature relating to the legends and demonic figures principally of the Strigoi and Moroi, fundamental to understanding that culture in which the myth of the vampire originates. We will let ourselves be led into the land of Dracula by some important local ethnographers such as Romulus VulcÇnescu and Simeon Florian Marian. To delve into the theme, we will discover the symbolic and anthropological aspects conserved in the myths that we will find, comparing them, also with other analogous supernatural beings present in Central Europe. According to VulcÇnescu, the Strigoi (a term that derives from the Latin strix and that means strega in Italian [witch in English]) are among the mythical beings that have greater importance in the Romanian demonology tradition. There are two types of Strigoi: the so-called Strigoi vii (living) and the Strigoi mort (dead). While the Strigoi mort, effectively, can well number among the non-dead which, although not sucking peopleâs blood, commit atrocities of every type, the Stringy vii are living witches and wizards who can occasionally kill but do not have the powers traditionally associated with vampires: they will become vampires, in fact, after their death. As regards Romania, VulcÇnescu states that there are some precise characteristics that identify a living Strigoi, comparable, therefore, to a witch in flesh and bone. These characteristics are associated with persons really existing and who, by societyâs need to find a scapegoat, were identified as witches. The Romanian ethnographer recounts that you can be a Strigoi from birth or become one if, during your life, you convert to the cult of the Devil. The descendants of a Strigoi can be hereditary in the case in which there is found in the genealogy the presence of a Strigoi of a Strigoaice [female Strigoi]. One can discover if a person belongs to this lineage by various means: if, for example, a baby is the seventh child, and is preceded by all male brothers (or all female, according to a Polish tradition), it is born with a part of the placenta on its head and swallows it immediately after being born; if it had an equine foot; or, finally, if its hair is reddish and the base of the spine ends in a tail covered in hair. Some physical characteristics or behaviour also identify a baby Strigoi: he, in fact, has a precocious development, is strong and evil, tortures and kills animals, takes pleasure in being malicious, lies, cheats, steals and swears. As an adult, you can recognise the Strigoi by its generally hairless look, by the bloodshot eyes, by the more pronounced canine teeth and by the coccyx which is longer than normal. From a behavioural point of view, it is marked by the evil actions that it performs. In the female, these beings are called Strigoaice: they have origins completely similar to the Strigoi and the same physical characteristics, but, in their behaviour, they are much more brutal. The people who are identified as witches bringing misfortune can be recognised by some distinctive traits that are found spread all over Europe. The most common physical characteristics that mark them out were the ugly look, sometimes due to the signs of poverty and misery. From the physical aspect point of view there have been merged, from ancient times, characteristics of witches that remain impressed on our minds still today in popular tradition: curved fingernails like wolfsâ claws or the talons of raptors, bad teeth, even though capable of tearing you to pieces with incredible ferocity and, finally, their heads could be bald or have dishevelled hair. Even women who assumed strange behaviour were looked upon with diffidence. Among the characteristics of witches, with the Romans we find those known as nocturnal vampires, the total aversion to light and the exsanguinated pallor of the face, an unequivocal sign of death. According to Festo, Strix (âStregaâ in Italian [âwitchâ in English]) is the name given to evil women also called âvolatileâ [âflyingâ in English]. Flight in fact is for Latin authors a common and distinctive element of these terrible beings. There is not always agreement on which volatile can transform itself: the owl is often identified, but Plinio the Elder presupposes that it can also be the bat. Over and above these comments the most symbolic example is that of the female Striges on the cradle of Proca from Ovid. The passage reports meticulously the meal of this horrendous creature. They say - writes the Latin author - âthat with their beaks they tear open the entrails of suckling babies and that they fill their throats drinking the bloodâ. These descriptions in the sphere of the ancient world of witches, cruel blood-thirsty beings, find corresponding elements in narratives kept in the popular tales handed down right up until our days. Alberto Borghini, for example, in his Semiosi in folklore 2, reports two accounts in which some witches suck the blood of young victims: the first collection in the Garfagnana valley in Tuscany in Italy, the second in the Piedmont region of Monferrato-Langhe [in central Italy]. The analogies and reports of winged, blood-sucking beings are so persistent as to constitute, according to the scholar, a real âidentity of a narrative typeâ. Over and above these examples, in general terms, the people identify witches with those persons that went beyond conventional behaviour. There could be considered as witches even those people who had had problems, or because they were present at the moment of some misfortune. Moreover, the character of the persons or some physical deformity could be indicative: a surly and withdrawn temperament or a woman with a bent back offered further indications. In any case, they were considered to be marginalised people or otherwise outside the social group or poor beggars. Sometimes it was the territory that was considered inhabited by witches, or it was considered that they lived in remote areas or, again, that they lived in ugly, small and dirty or isolated houses. Also, some specific illnesses, like for example epilepsy, denounced them as belonging without doubt to accursed women. In some communities, the negative powers were handed down from generation to generation. It was considered that these persons could do evil or bring misfortune: meeting them meant having adverse consequences in life, regarding the people or the outcome of the agricultural season. The general idea was that because of meeting them something bad would certainly happen and that nothing could be done to change the course of events. The witches were, therefore, hated and respected at the same time and, anyway, you tried to keep as far away from them as possible. Among the behaviour arousing suspicion was moving house often. Some situations of living independently, like being an orphan or being raised by prostitutes, could arouse strong suspicions. Moreover, suicide or premature death constituted implicit admission of being one of the terrible witches. The lowest common denominator of the examples given up until now leads to the anomaly, the physical difference compared with so-called normality. In the case of the unfortunate meeting with one of these terrifying crones, the appropriate exorcism was resorted to, sharing with others the fear that the witch could cast some kind of spell. Women who were identified as witches lived a wretched life because they were unpopular and avoided by everyone. They answered to the need of the community to identify a scapegoat, in order to project all their personal and social tensions. There were some cases, then, in which those persons that were identified with the pejorative name of witches were not only humiliated, persecuted or beaten, but even killed. In Romania, as in the rest of Europe, the scourge of religious persecution was put down: records of trials of witches that were held in the period between 1463 and 1777 report faithfully, sometimes even with too much precision (not to say with a bit of complacency), the account of the confessions and the executions. In this country, they were accused of blasphemy, holding black masses, cannibalism, criminal rituals (above all, infanticide). The persecution occurred particularly in Transylvania, which in the Middle Ages was Hungarian territory. The inquests that they had in this region were numerous over the centuries and there were repeated convictions with brutal cruelty. In 1686, for example, the wife of the prince of Transylvania, Michael Apasi, I went mad and the witches were blamed; a vast inquest was conducted, following which the flames of the burnings at the stake flared almost everywhere in this region. Even after the end of the legal persecutions, the firm beliefs on witchcraft remain deep-rooted. In Transylvania, they believe that leading the nocturnal flight over the rocky mountains was the mythical Meneges: the noisy mythological figure capable of carrying out extraordinary magical deeds. Still in the last century there were cases in which they believed that nocturnal witchesâ Sabbaths were held; their inhabitants abandoned them and they remained empty; many places where it was considered that the witchesâ Sabbaths were held had a very bad reputation. Another Romanian belief concerning the male Strigoi, was that they had a nocturnal existence that began at midnight and lasted until the first cock-crow. During sleep, their souls came out of their mouths and, in the form of human shadows, the Strigoi went around the villages or the farms of their parents, their neighbours and fellow countrymen doing every reprehensible thing that came into their mind: they dried up the orchards, they took out the nutrients from the wheat and the milk and poisoned the springs. They became invisible and in this way, without anyone being able to identify them, they could call out to people by name, frighten them, disfigure travellers and knock over the objects in the courtyard and in the houses they entered. At the third crow of the cock, however, the spirit of the Strigoi had to return to its body. It was said that they had such a deep sleep that on reawakening they did not remember any more what they had done during the night. Only if courageous men had had the strength to tackle them and slash them with a particular sign on the face would their true identity have been discovered. These legends are born from the most ancient fears present in man, like, for example, for the beings that populated the night from the moment of dusk falling. The thing, that man has always thought was absolutely his deepest anxiety, is the darkness without any precise form, witches are in that regard both the impersonal representation of this anguish but also, through a physical form, the attempt to diminish the horrific emotional charge. Witches, in fact, dressed in black, or transformed into black cats, can be confused with the darkness of the night to carry out evil deeds. When in a village there lacks concrete proof to recognise the culprits, like in the case of identifying a witch, proof can be found in disabled people who, transformed into black or invisible animals, are held culpable of every kind of malice. In Romania, they said moreover that when men go out at midnight, behind their houses or to the crossroads, they made three somersaults and transformed themselves even into wild beast-men, horse-men, wolf-men or wild boar-men. Thus transformed, they wandered around the village, along the roads between the villages, on the hills, along the riverbanks and between the meadows of the forest, carrying out cruelties. At times they road on magic sticks, brooms or pâserâ maiastrâ (magic birds) to circle the world far and wide and to make their enemies, or those suspected of being so, ugly. This aspect of the flight of the witch is a rather complex mythological element that is found in many traditions, not only European, therefore a wider description of it will be given later in this book. Every year the Strigoi men meet for three nights in a sort of Walpurgis Night festival on the feast of Saint Theodore, Saint George and Saint Andrew. On Saint Theodore, the Strigoi men transform themselves into the horses of Saint Theodore, kinds of centaurs which went around to punish the girls and women who did not respect their festival. In thinking about the origins, so that good luck is preserved, it is necessary to observe both the obligations and the prohibitions. The legends characterised by the prohibitions, or rather, the âdo-notsâ, underline the rules that must not be infringed in absolutely any way, because, on non-compliance with the rules, there will ensue an inevitable and terrible punishment. They recounted a time in Romania when, on the anniversary of Saint George (23rd April), the Strigoi