0

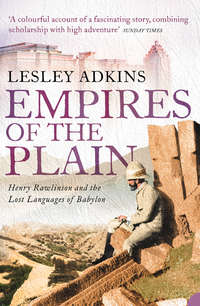

0Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon

Nearly five years earlier, despite the chill of gloomy, showery spring weather, Wednesday 11 April 1810 had been a day of rejoicing for Abram and Eliza Rawlinson, when their second son was born at Chadlington in north Oxfordshire. Henry’s birth came at a time of continuing upheaval and worry in Europe. That same month Napoleon’s troops began to annex Holland, and the Emperor himself married Marie-Louise, Archduchess of Austria, while France headed towards deep economic crisis. As the year wore on, the Napoleonic Wars were concentrated in Spain and Portugal, where the British troops fought the French under the command of Wellington. In Britain King George III’s mental condition deteriorated, and the following year he was declared insane; his son the Prince of Wales, the future George IV, ruled in his stead as the Prince Regent.

The Rawlinson family had already grown many branches, but their roots were in Lancashire in northern England – respectable but hardly noteworthy members of the gentry, who owned land mainly in the isolated Furness area. The derivation of the surname remains uncertain, possibly ‘son of Roland’, as in the associated surnames Rowlinson and Rollinson, yet these names occur in Lancashire only from the sixteenth century, decades later than Rawlinson. One of Henry’s ancestors was Daniel Rawlinson, a wealthy London vintner, tea merchant and keeper of the Mitre Tavern in Fenchurch Street, much frequented by his friend and neighbour Samuel Pepys until its destruction in the Great Fire of 1666. Daniel’s son Sir Thomas Rawlinson, who inherited his estates and businesses, was Lord Mayor of London in 1705–6. His own eldest son Thomas developed a passion for books and manuscripts, amassing over 50,000 volumes and 1,000 manuscripts that were eventually sold to settle his debts. This unpalatable task was forced upon his younger brother Richard, himself a book collector and antiquary, who in 1750 set up an endowment for a professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University. Now called the Rawlinson and Bosworth Chair of Anglo-Saxon, its most notable incumbent was J. R. R. Tolkien. Another Anglo-Saxon scholar was Henry’s ancestor Christopher Rawlinson, born in 1677, who is most famous for having prepared and published an Anglo-Saxon edition of King Alfred’s translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy.

Although Henry was not directly descended from Daniel and Christopher, they could all trace their roots back to two brothers, William and John, in the reign of Henry VIII. Earlier still the family tree lacks detail, but ancestors certainly served at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 under Henry V, who awarded the Rawlinson coat-of-arms that has three silver-bladed swords with gold hilts on a sable ground, and for the crest a lower arm sheathed in armour, with the hand grasping a sword. Henry’s own father, Abram Tyzack Rawlinson, was the elder of the twin sons of Henry Rawlinson, a merchant and Member of Parliament for Liverpool who married a Newcastle upon Tyne heiress, Martha Tyzack. The twins’ father died in 1786 when they were nine years old, but they continued to live at Caton near Lancaster, in the ancestral home of Grassyard (now Gresgarth) Hall. Here Abram and his twin Henry Lindow were raised by their mother and subsequently educated at Rugby School and Christ Church, Oxford, where they concentrated on sporting, not educational attainment. On inheriting Grassyard Hall and its estate, Abram promptly sold up and began to look for an estate ‘in the more civilised part of England’,1having come to despise northern England ‘for its roughness, its coarseness, and its “savagery”’.2 In August 1800 at St George’s Church in Hanover Square, London, he married Eliza Eudocia Albinia Creswicke, who had inherited the enormous sum of £20,000 from her deceased brother Henry.

Six years after his marriage to Eliza, Abram bought a 700-acre agricultural estate at Chadlington, an ancient pre-Domesday village just south of Chipping Norton and 13 miles north-west of Oxford – close to his wife’s former home at Moreton-in-Marsh. The spacious L-shaped manor house at Chadlington, where Henry Creswicke Rawlinson was born and spent his childhood, was built of Cotswold stone and was separated from the medieval church of St Nicholas and the village to the north by a belt of trees, while in front was a lawn terrace, a ha-ha and a hay meadow. The extensive view across the Evenlode Valley first took in clumps of elms and oaks in the meadow, with fields and copses beyond as far as the river, while the extensive Wychwood forest covered the hillside in the distance. It was a perfect place to live.

For much of the day Abram rode from field to field, watching over the running of his largely arable farm, talking to the labourers and discussing business matters with his bailiff. The months of September and October were occupied by shooting and the rest of the autumn and winter by riding with the Duke of Beaufort’s hunt. Another of Abram’s passions was the breeding and training of racehorses, in which he had several successes, and he was also involved in civic duties as a Justice of the Peace and a Deputy-Lieutenant of Oxfordshire.

When Henry was born, he was the seventh, but not the last, of Abram’s children – he and his older brother Abram and sisters Anna, Eudocia, Maria, Georgiana and Caroline were soon joined by four more brothers – Edward (who died only a few months old), George, Richard and, three months after the Battle of Waterloo, another Edward. At a time when a farm labourer was earning less than £30 per year, the income of the Rawlinson family in good years was around £2,000, partly from property Abram had inherited in the West Indies, but primarily from the farm. The ending of the Napoleonic Wars in June 1815, though, witnessed a period of severe agricultural depression in Britain that affected income from the land, and freak weather the following year led to harvest failures, starvation, unemployment, bankruptcies, increased emigration, demonstrations and riots. Although Abram sent his eldest son to Rugby School, he was forced to economize on the education of the other boys during this period of financial uncertainty, and so up to the age of eleven Henry attended a day school at Chadlington and was also educated at home by his mother, learning Latin, English grammar and arithmetic, supplemented by lessons from his sisters’ governesses.

Not only did Henry spend his early years in rural Chadlington, but also in the contrasting environment of the city of Bristol. For over five years, from the time the Royal Scots Greys marched to Waterloo, he often lived with his maternal aunt Anna and her husband Richard Smith, in their elegant terrace house at 38 (now 80) Park Street, and for a short while attended a day school in the city. Richard Smith was a surgeon to the Bristol Royal Infirmary, and he successfully treated his nephew’s serious eye condition that had threatened his vision, so that in the end only his left eye was partially impaired. When Henry was seventeen years old, he was told a story about ‘good Aunt Smith’s marriage’, that she was engaged to Henry Pelly, but he went to sea to make his fortune, and on returning discovered that Anna, like Henry’s own mother, had inherited a fortune. He was too proud to approach her, and because she was annoyed at being ignored, Anna eloped with another admirer, Richard Smith. In view of Henry’s sight being saved, this was a happy outcome, and he himself noted: ‘Who that has seen their perfect content and happiness will ever believe in the inevitable miseries of an elopement.’3

At Bristol, Henry came under the influence of his aunt’s wide literary circle, including Hannah More, a poet and playwright who had achieved great success in London and whose hugely popular religious tracts aimed at the reform of conditions for the poor had led to the founding of the Religious Tract Society in 1799. She was then living at Wrington in Somerset, to the south-west of Bristol, where Henry’s maternal grandmother also had her home. From 1813 his aunt’s closest companion was Mrs Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, an author of popular religious and educational works and a campaigner for the abolition of slavery. She often talked to Henry, who recorded that she ‘took a great interest and taught me scraps of Hebrew’,4 which she herself was studying with his aunt.

In January 1821, eight months after the death of his eleven-year-old sister Caroline, Henry was sent to a boarding school at Wrington. He later condemned his two-and-a-half years there as of limited use, because he ‘got well grounded in Latin and Greek. Also in General History but learned no Mathematics’.5 Much more influential for him must have been spending nearly every Sunday in the company of Hannah More and her supporters. A few weeks after starting this school, just before Easter, Henry undoubtedly heard about his uncle’s involvement with John Horwood, hanged at Bristol’s New Gaol on Friday 13 April for murdering a woman who had rejected him. By order of the court, Horwood’s body was released to Richard Smith at the Bristol Royal Infirmary for dissection, which was carried out before a large audience and was followed by several lectures. Smith had an account of the trial, execution and dissection bound into a book that was covered by Horwood’s own tanned skin – a macabre volume now held in the Bristol Record Office.

Henry’s older sister Anna Maria died in 1823, and in August the following year he was moved to the much larger Great Ealing School, then considered to be ‘the best private school in England’.6 Although now swamped by the suburban spread of London, the village of Ealing was predominantly agricultural, dotted with fashionable country houses. Henry judged his two-and-a-half years at this school to have been crucial, because for the first time he developed a desire to excel in academic studies rather than just in sports. He acquired such a good command of Classical languages that by the time he left he was first in Greek and second in Latin within the entire school, a substantial accomplishment considering his previous piecemeal education. Even so, he had no intention of going to university, as he had long cherished an ambition to seek adventure by entering the army; apart from his nickname of ‘Beagle’, from an early age his brothers and sisters called him ‘the General’.7

Although diligent in his school work, Henry was a strong character, not above breaking the rules when it suited him. On one occasion he was caught with another boy, Frank Turner, after they had walked to and from London to see an opera. The penalty for such a premeditated breach of the school’s strict discipline could be harsh – flogging or expulsion. Instead they were set the task of learning by heart, in the original Latin, all 476 lines of the Ars Poetica, written by the Roman poet Horace around 19 BC in the form of a letter giving views on the nature of poetry. After a fortnight, Henry completed the task and recited the lengthy poem without a flaw, but the other boy failed and was expelled.

As might be expected from a family background so steeped in field sports, Henry had a natural talent for all the games played at the school: prisoners’ base, cricket, football and fives. He was exceptionally gifted at fives, a rough ball game that required great physical endurance, using the hands rather than bats or rackets. He spent the school holidays at Chadlington entirely immersed in the outdoor pursuits of hunting, shooting and fishing, and at times was invited by Lord Normanton to attend shooting parties with his father in the woods east of Chadlington that formed part of the Ditchley Park estate. On his first occasion Henry shot and killed every pheasant before Lord Normanton had taken aim, and so he had to be advised of the correct etiquette. He then held back, only to prove himself the best shot after Lord Normanton had fired – in the sporting slang of the time, ‘wiping his lordship’s eye’.8

In December 1825, Henry’s older sister Eudocia died at Bristol at the age of twenty-three. Five months later, when he was sixteen years old, Henry left school with a nomination to a cadetship in the East India Company, a position he owed to the influence of his mother’s half-brother, although his formal nominator was William Taylor Money, one of the Company’s directors. Henry was now 6 feet tall (6 inches above the average height at the time) and was ‘broad-chested, strong limbed, with excellent thews and sinews, and at the same time with a steady head, a clear sight, and a nerve that few of his co-mates equalled’.9 In fact, with all the qualities of a young soldier.

For the sons of gentry, entering the British army as an officer meant buying a commission and having a private income to supplement the low pay, but this burden could be avoided by entering the army of the East India Company as a cadet and rising through the ranks by promotion – which Henry Rawlinson proposed to do. Granted a charter on the last day of December 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I, the East India Company (more correctly ‘The Governor and Company of Merchants of London, Trading into the East Indies’) had exclusive rights to trade with the ‘East Indies’, a term covering the entire south-east expanse of Asia. Initially, the Company competed with the Dutch for the Indonesian spice trade, but after the ‘Massacre of Amboyna’ in 1623 when Company merchants and their servants were tortured and executed by the Dutch, the Company turned to the subcontinent of India.

In the mid-eighteenth century the East India Company was still a purely commercial company, importing and exporting goods from its bases at Bombay on the west coast, Madras on the east coast and Calcutta on the Hooghly River in the north-east. So successful was its business that it was able to loan money to the British government, but all this began to change, because conflict with the French and the crumbling of the Mughal Empire provoked the Company’s intervention in political and military struggles in India, initially in the south and east. In 1756 the new nawab (ruler) of Bengal captured Calcutta, where scores of his prisoners suffocated in an airless room, an incident dubbed ‘the Black Hole of Calcutta’. In revenge, the Company’s army, led by Robert Clive, recovered Calcutta and took control of the entire province of Bengal. The land tax revenue from this new territory enabled the Company to build up a sophisticated civil service and an extensive army, which gave them the means to conquer further territory and defeat the French.

By this time, many Company employees found themselves able to amass huge fortunes, often by unscrupulous means, while soldiers and officers were eager for further military campaigns because of the resulting opportunities to acquire loot and prize money. These ‘nabobs’ (a corruption of nawab) would retire to Britain with their new wealth, causing much resentment of their lavish lifestyles and their efforts to gain political advancement. Perceived as being answerable only to its shareholders, the Company was the target of several hostile government reports, and with mounting debts, the Company’s Board of Directors was obliged to accept a degree of government control under Acts of Parliament in 1773 and 1784.

The East India Company, also known as John Company, became primarily an administrative rather than a commercial body, acting as an agent of the government and no longer relying on trade, but on the collection of land taxes from the territories it ruled. The Governor of the Bengal Presidency, based at Calcutta, was now also the Governor-General of India, exercising superiority over the Bombay and Madras presidencies. By the time Henry arrived in India, large swathes of the area now divided into India and Pakistan were ruled by the Company through conquest, or indirectly through alliances with hundreds of small states ruled by Indian princes. The Company’s army was 300,000 strong and was split between the three presidencies; it accounted for over three-quarters of the Company’s expenditure. Most of the East India Company troops were native sepoys (from the Persian word sipahi, ‘soldier’) and their officers were mainly British, but all were regarded as inferior to the regular British army, a judgement based on class rather than efficiency.

Having been nominated directly, Henry could have sailed for India immediately, as he was not obliged to attend the Company’s Military Seminary at Addiscombe, near Croydon. Instead, he chose to receive private tuition from Thomas Myers, a mathematician and geographer and formerly a professor at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich. Myers was now living and teaching at Blackheath village, a small and affluent suburb just over 5 miles south-east of London. ‘Here’, Henry noted, ‘I learned Hindestanee and Persian, surveying, advance Mathematics, Military drawing, fencing and all other requisites for an Indian soldier’s life.’10 Numerous languages were spoken throughout India, but it was important to have some knowledge of the Hindustani language (known today as Urdu), because it was the main language of communication between East India Company officials and the natives. It had its origins in the Muslim courts and cities of northern India. For hundreds of years Persian had been the language of administration in India, although by the nineteenth century the version of Persian used in India was very different to the language used in Persia. In Persian, Hindustan meant ‘land of the Hindus’.

Impatient to embark on his new career, Henry regarded the six months spent at Blackheath with Myers as wasted. By the end of 1826 he was ready to leave on the first available ship for India, but was destined to be disappointed, because early in the new year he fell ill of typhus fever during an epidemic at Bristol when he was staying with his aunt and uncle. He was looked after by his beloved sister Maria and for that reason he later remembered this moment as one of his happiest. Spring and summer 1827 were spent in convalescence at Chadlington in the continuous company of his three younger brothers George, Richard and Edward, who were also home from school following a bout of the fever. Henry ordered them to do constant broadsword exercises, while he entertained them with tales of the war with Burma and graphically hacked the trunk and lower branches of a tree near the house in imitation of the terrible wounds he intended inflicting on his barbarian opponents. This was an idyllic time for Henry and his younger brothers, all innocent of the fact that one of them would be dead and the rest grown men before Henry set foot in England again.

After the long months of waiting, the seventeen-year-old nearly missed setting sail for India. Thinking there was time to spare, he had gone to see one of his father’s horses win in the races at Cheltenham, but a messenger rushed up to him with the news that the ship was about to leave London Docks for Portsmouth. Hurrying back to London, Henry managed to get kitted out and rapidly purchased around one hundred books. Even without the necessity of buying a commission, it was still an expensive undertaking to send Henry as a cadet to India, as his passage alone cost over £100, while his father spent a further £500 on his kit, and he himself would only be paid from his arrival at Bombay. Henry managed to reach the south coast just before the 644-ton chartered ship Neptune set sail for Bombay from Portsmouth harbour on 6 July 1827. An old East Indiaman vessel built in 1815, it was captained by its owner John Cumberlege.

The Neptune followed the fastest route available, around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, but even so the journey lasted four months. From the outset Henry was desperately homesick, missing above all else his two surviving sisters, Maria and Georgiana. Having promised Maria that he would keep a journal to send home, he often recorded his adolescent feelings of misery and anxiety in a style that was intimate, spontaneous, often poetic and lacking the polished structure and formality of his later writing. He began the journal on his very first day: ‘Shook hands with my brother Abram and stept into the boat at Portsmouth which was about to bear me from my native shore, to exchange the society of parents, friends, brothers and sisters whom I love with an affection never to be shaken for a life of misery and sorrow among strangers and barbarians. During my crossing over to the ship the beautiful blue waves, glittering beneath a July sun and placid as the calm I once enjoyed, lulled my feelings into something like repose, and I reached the ship Neptune in a species of mental stupefaction … The calling of the sea makes any head so giddy that I can hardly tell what I am about, and my fellow passengers so disturb my attention that it is only when I sit by myself on the poop and view the moon beams glancing on the silvery sea that I can believe I am wretched, miserable, alone, in one word that I am an exile.’11

Three days later, he felt no better: ‘It is now Saturday July 7th 6 o’clock in the evening and I am sitting alone in my cabin writing this commencement to my journal. Maria, if your bright blue eyes should ever chance to rest on these promised pages, know that I am now thinking of your lovely face which, perchance, I never may behold again, and I swear that I may be destined to pass the remainder of my days in banishment and misery. Whenever the natural instability of my disposition may bring me to engage in a quarrel, I will think of your angelic form, and I shall be the coolest of the cool, and though you seem to think that I shall never remember you, be informed that not a day or an hour will ever elapse without your sweet face being presented to my memory, and whatever may be my fate, prosperous or unhappy, good or bad, I never never will forget you. I think I have been writing a great deal of nonsense which can be of no interest to anyone, but I was alone, I was unhappy, the bitterness of my feelings seemed to overpower my understanding, and I have shed tears of the bitterest anguish. We are now sailing down the channel at the rate of 9 knots an hour, but every league I proceed adds but another link to the chain of my misery, for I am sailing farther and farther away from everything which I love in this world. I intend commencing hard fagging [hard work] as soon as this cabin, which I have with another man of the same following, is in tolerable order … now for a tune on my flute and then a walk upon deck.’12

The next day, Sunday, Henry wrote: ‘I am in rather better spirits today, I am come down to my cabin to proceed with my journal. We are sailing down the channel at a tolerable pace and they say today we shall pass Land’s End.’13 Although less homesick, he was awkward and unhappy in his relationships with the other passengers, being constrained by etiquette in approaching them. He felt especially ignored by Sir John Malcolm, who was on his way to Bombay to take up the governorship: ‘Sir John now speaks to every other passenger on board except me, and as I cannot get introduced to him I see no probability of our ever conversing.’14 Misery again overwhelmed Henry: ‘I am sure I shall hate India and [wish] that I was once more in England – could I but once more see Georgiana and Maria, there is no situation however menial that I feel at present I had not rather undergo in my native land than be a private among strangers and savages … the rest of my life will be merely a mechanical employment of the body … I cannot write without becoming unhappy so I had better conclude for the present and read Scott’s Life of Napoleon.’15

The advice given in The Cadet’s Guide to India was to pass the time usefully and ‘to devote two or three hours in the morning to the study of the Hindoostan language; then let reading, or drawing, fill up the space after dinner, after which he [the cadet] will be at leisure and like to walk the quarter-deck with his companions, or partake of their rational sports’.16 Henry began to follow this advice, as seen in his journal entry for 9 July: ‘It has been a very uncomfortable day and I have been all day in my cabin reading, fagging and playing the flute. Begin to get rather more comfortable, though I cannot as yet reflect with any comfort on my future destiny. Until I become tolerably habituated to banishment, I should deem it best to think as little as possible of my former happiness … Maria and Georgiana – I still think of you, and whatever pain the thought may cost me, the recollection of my home and infancy shall never be forgotten.’17