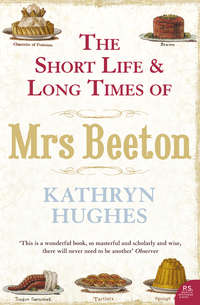

The Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton

As William’s eldest son, Henry Dorling gradually took over the running of the business. His appointment as Clerk of the Course in 1839 was a recognition of the family’s growing involvement in Epsom’s chief industry. But there was only so much that the position allowed him to do in the way of cleaning up the moral slurry that was keeping respectable people away. To have real influence, to pull Epsom together so that it was a smoothly integrated operation, Dorling would need to take control of the Grandstand too. When it had opened in 1830 the Grandstand had been the town’s pride and joy. Designed by William Trendall to house 5,000 spectators, it had cost just under £14,000 to build, a sum raised by a mixture of mortgage and shares. The imposing building – all Doric columns, raked seating and gracious balconies – was designed to combine the conveniences of a hotel with the practicalities of a head office. According to the Morning Chronicle, which puffed the grand opening on its front page of 12 April 1830, the Grandstand incorporated a ‘convenient betting room, saloon, balcony, roof, refreshment and separate retiring rooms for ladies’. And in case any readers of the Morning Chronicle were still doubtful that Epsom racecourse really was the kind of place for people like them to linger, they were assured that ‘The whole arrangement will be under the direction of the Committee, who are resolved that the strictest order shall be preserved.’

From the moment that the Grandstand had first been mooted back in 1824, the Dorlings had been eyeing it hungrily. William Dorling had been canny enough to buy some of the opening stock, and by 1845 Henry was the single biggest shareholder. Early on, in 1830, William suggested that he might put the prices of entry on the bottom of Dorling’s Correct Card, a stealthy way of identifying the name of Dorling with that of the Grandstand. Although the Grandstand Association initially rejected the idea, by the time of next year’s Derby the prices are firmly ensconced at the bottom of the card, where they would remain for over a century. William Dorling’s hunch about Epsom’s promise had paid off after all.

But by the 1840s, and despite all that ‘strictest order’ promised by the committee, the Grandstand was not quite the golden goose that it had once seemed. Its early glamour and promise had leaked away and it was no longer turning a profit. Now that people came to think about it properly, it was not actually very well placed, being parallel to the course and unable to offer more than a partial glimpse of the race. The majority of visitors, everyone from Guards officers to clerks, preferred to follow the action from the Hill, the large high bank which offered a much better view of the entire proceedings. Having finished their Fortnum and Mason picnic (Fortnum and Mason so dominated the feasting on the Hill that Dickens declared that if he were ever to own a horse he would call it after London’s most famous grocery store), they simply stepped up onto their hampers in order to see the race. Unless a Derby-goer was actually inside the Grandstand – and increasingly there was no reason why he would wish to be – then not a penny did he pay.

In 1845 Henry Dorling became the principal leaseholder of the Grandstand, thanks to Bentinck’s strenuous string-pulling at the Jockey Club. This meant that Dorling was now in complete charge of all aspects of racing at Epsom. But in order to deliver the 5 per cent annual return he had promised the Grandstand Association on its capital, he would need to make substantial changes to the way things were done. So he came up with a series of proposals designed to make racing more interesting for the spectators, especially those who had paid for a place in the Grandstand. Horses were now to be saddled in front of the stand itself, where punters could look over their fancy (this already worked a treat at Goodwood and Ascot). And to make the proceedings more intelligible for those who were not already initiates, Dorling instituted a telegraph board for exhibiting the numbers of riders and winners. Races were now to start bang on time (Dorling would have to pay a fine to the Jockey Club if they did not) and deliberate ‘false starts’ by jockeys anxious to unsettle their competitors were to be punished. And, not before time one might think, Dorling put up railings to prevent the crowds surging onto the course to get a better view. Finally, and most controversially, he laid out a new course – the Low Level – which incorporated a steep climb over 4 furlongs to provide extra drama for the watchers in the Grandstand.

The fact that these changes were designed for the convenience of investors rather than devotees of the turf was not lost on Dorling’s critics. For every person who benefited from his innovations – the Grandstand shareholders, Bentinck, Dorling himself – there was someone ready to carp. Different interest groups put their complaints in different ways. The Pictorial Times of 1846, for instance, suggested that as a result of Dorling’s tenure of the Grandstand (only one year old at that point) ‘the character of its visitors was perhaps less aristocratic than of old; but a more fashionable display we have never met in this spacious and, as now ordered, most convenient edifice.’ In other words, the punters were common but at least the event was running like clockwork. The modern equivalent might be the complaint that corporate sponsorship of sport has chased away the genuine fans.

Within Epsom itself the opprobrium was more personal. By the end of his life Dorling had become a rich man and, according to one maligner, strode around ‘as if all Epsom belonged to him’. The obituary in which this unattributed quote appeared went on to add, in the interests of balance, that under Dorling’s reign there had been ‘no entrance fees, no fees for weighing, no deductions’ nor the hundred other fiddles by which clerks of racecourses around the country attempted to siphon off extra income. In other words: Dorling was sharp, but he was straight. Other carpers couched their objections to his dominance by attacking the new Low Level Course which, while it might provide excitement for the Grandstanders, was actually downright dangerous for the horses and jockeys. But, no matter how the comments were dressed up, the real animus was that Henry Dorling was simply getting too rich and too powerful. A letter of complaint written by ‘concerned gentlemen’ on 30 April 1850 can still be seen in Surrey Record Office: ‘we may add that it has become a matter of great doubt whether the office of Clerk of the Course is not incompatible with that of Lessee of the Grand Stand, especially as one result has been the recent alteration of the Derby Course which we hear is so much complained of.’ Henry Dorling’s gradual monopolization of power was beginning to stink of the very corruption that he had been brought in to stamp out.

The bickering rumbled on through the 1860s and 1870s, pulling in other players along the way. There were constant disputes, some of which actually came to court, over who had right of way, who was due ground rent, who was entitled to erect a temporary stand. Timothy Barnard, a local market gardener, had the right to put up a wood and canvas structure to the right of the Grandstand, which naturally narked the Association. Local grandees who disapproved of betting (and there were some) refused to allow their land to be used for the wages of sin. The overall impression that comes through the records of Epsom racecourse is that of a bad-tempered turf war, a contest between ancient vested rights and newer commercial interests. Everyone, it seemed, wanted a slice of the pie on the Downs.

By the time Charles Dickens visited Epsom in 1851 to describe Derby Day to the readers of his magazine Household Words, Henry Dorling was sufficiently secure in his small, if squabbling, kingdom to be a legitimate target of Dickens’ pricking prose:

A railway takes us, in less than an hour, from London Bridge to the capital of the racing world, close to the abode of the Great Man who is – need we add! – the Clerk of Epsom Course. It is, necessarily, one of the best houses in the place, being – honour to literature – a flourishing bookseller’s shop. We are presented to the official. He kindly conducts to the Downs … We are preparing to ascend [the Grand Stand] when we hear the familiar sound of the printing machine. Are we deceived? O, no! The Grand Stand is like the Kingdom of China – self-supporting, self-sustaining. It scorns foreign aid; even to the printing of the Racing Lists. This is the source of the innumerable cards with which hawkers persecute the sporting world on its way to the Derby, from the Elephant and Castle to the Grand Stand. ‘Dorling’s list, Dorling’s correct list!’ with the names of the horses, and colours of the riders!

But there were limits even to Dorling’s ascendancy. No amount of cosy cooperation with Lord George Bentinck–Bentinck lent him £5,000 and Dorling responded by giving his third son the strangely hybrid moniker William George Bentinck Dorling – was going to turn Dorling into anything more than a useful ledger man as far as the aristocrats of the Jockey Club were concerned. Dorling, a small-town printer, had made a lucky fortune from Epsom racecourse and that, as far as the toffs were concerned, was that. One family anecdote has Henry complaining to his new wife Elizabeth that being Clerk of the Course was not a gentleman’s job. She was supposed to have replied, ‘You are a gentleman, Henry, and you have made it so.’ But both of them knew that, actually, it wasn’t true.

The new home to which the just-turned-seven Isabella Mayson arrived in the spring of 1843 was simply the Dorlings’ sturdy High St business premises. But by the time Dickens visited Epsom eight years later she had moved with her jumble of full, step and half siblings into one of the most imposing residences in the town. Ormond House, built as a speculative venture in 1839, stood, white and square, at the eastern end of the High Street, usefully placed both for driving the 2 miles up to the racecourse and for keeping a careful eye over the town’s goings-on. A shed adjacent to the building housed the library and, initially, the printing business too. For all that Dickens described Dorling in 1851 as a ‘great man’ with a house to match, the census of that year tells a more modest tale. By 1851 there is just one 16-year-old maid to look after the entire household which includes fifteen-year-old ‘Isabella Mason’ [sic], and a permanent lodger called James Woodruff, a coach proprietor. Whatever Epsom gossips might have said, it was not until the 1860s that Dorling really began to live like a man with money.

The emotional layout of the newly blended Mayson-Dorling household is harder to gauge. Initially there were eight children under 8 crammed into the house. The four children on each side matched each other fairly neatly in age, with Henry Mayson Dorling just the oldest at 8, followed by Isabella Mayson, a year younger. At the outset of the marriage Henry Dorling had promised that ‘his four little Maysons were to be treated exactly the same as his four little Dorlings’ and, in material terms, this certainly does seem to have been the case. There were no Cinderellas at Ormond House. The Mayson girls received the same education as their Dorling stepsisters and, as soon as he was old enough, John Mayson was integrated into the growing Dorling business empire along with Henry’s own sons. On Henry’s death in 1873 his two surviving stepchildren, Bessie and Esther, were left £3,000 each, a sum that allowed them to live independently for the rest of their very long lives.

The new Mr and Mrs Dorling quickly went about adding to their family. Charlotte’s birth, an intriguing seven and a half months after their marriage, was followed by another twelve children in all, culminating with Horace, born in 1862 when Elizabeth was 47. In total the couple had twenty-one children between them, a huge family even by early Victorian standards. People didn’t say anything to their faces, but there must have been smirking about this astonishing productivity which Henry, a touchy man, did not find funny. By 1859, 13-year-old Alfred Dorling was clearly feeling embarrassed by his parents’ spectacular fertility. As a joke, the boy sent his papa a condom anonymously through the post. Henry Dorling was not amused: condoms were the preserve of men who used prostitutes and were trying to avoid venereal disease, not of a paterfamilias who wished to limit the size of his brood. In effect, Alfred Dorling was calling his mother a tart and his father a trick. His punishment was to be sent to join the Merchant Navy where presumably he learned all about condoms and a great deal more. That Alfred drowned in Sydney harbour three years later is no one’s fault. And yet, given the way that anecdotes get compressed in their retelling, it is hard to avoid the impression that it was Henry’s awkwardness over his sexual appetite that was responsible for the death of his teenage son.

What was 7-year-old Isabella like, as she packed up her toys in the City of London, and prepared to move to Epsom? Over the previous three years, she had lost her father, been sent to live on the other side of the country with an old man she didn’t know, acquired a new papa and was now being moved from her home in Cheapside to a grassy market town. She had also acquired four stepsiblings and was now obliged to share her mother with a series of exhausting new babies who arrived almost yearly. The one thing she would have picked up from the tired and distracted adults who bustled round her was that there was no time and space in this hard-pressed world for the small worries and anxious needs of one little girl. The best thing she could do – for herself and other people – was to become a very good child, one who could be guaranteed never to make extra work for the grown-ups. And so it was that in order to distance herself from the chorus of tears, tantrums, dripping noses and dirty nappies that surrounded her in a noisy, leaking fug, little Isabella Mayson became a tiny adult herself, self-contained, brisk, useful. A sketch executed by Elizabeth Dorling in 1848 shows the entire family, at this point consisting of thirteen children, gathered in a jostling group. Elizabeth, who puts herself in the picture, is in a black dress and white cap and is nursing the latest baby, Lucy. Henry, dishevelled and standing slightly apart, gazes wild-eyed on the sketchy crew of small dependants as if contemplating how on earth he will cope. The only other figure who is properly inked in is Isabella, who stands immediately behind Elizabeth. She is wearing a black dress and white cap identical to her mother’s, with the same centre-parted hairstyle. In her arms she holds a wriggling toddler on whom her watchful gaze is fixed. She is 12, going on 25.

Soon Isabella’s nannying duties were expanded even further. As the clutch of children increased, it soon became clear that Ormond House could not hold the growing Dorling brood. The noise alone was unbearable: one day Henry Dorling, disturbed by the din, stuck his head around his study door and demanded to know what was going on. ‘That, Henry,’ Elizabeth is reported to have said, ‘is your children and my children fighting our children.’ The solution, though, was close at hand. The Grandstand was not needed for all but a few days a year. It would provide the perfect place to store extra children, those who were old enough to leave their mother but not yet sufficiently independent to be sent away to school. In this satellite nursery, housed in a building that resembled a stranded ocean liner on a sea of green, the little Dorlings would be watched over by Granny Jerrom and sensible, grown-up Isabella.

The fact that Isabella Beeton spent part of her youth in the Epsom Grandstand has insinuated itself into her mythology, until the idea has become quite fixed that she spent years at a time up there, running a kind of spooky orphanage. This, as commentators have been quick to point out, could not be in greater contrast to the cosy intimate atmosphere that Mrs Beeton urges her readers to create for their own families: ‘It ought, therefore, to enter into the domestic policy of every parent, to make her children feel that home is the happiest place in the world; that to imbue them with this delicious home-feeling is one of the choicest gifts a parent can bestow.’ What has been missed, though, in the rush to point out the discrepancy between Mrs Beeton’s advice and her personal experience, is the fact that in the first half of the nineteenth century it was entirely usual for tradesmen to shunt their families round in this way. Grocers, drapers, and chemists all used their premises flexibly, sometimes raising an entire family over the shop, and at others sending some of the children to live in other buildings associated with the business. The Dorlings’ decision to use the Grandstand as an annexe to Ormond House may seem odd to us now, but to their Epsom neighbours it was simply the way things were done. No more peculiar than the fact that the now elderly William Dorling had moved out of Ormond House and gone to live with his daughter at the post office in the High Street. People were more portable than buildings.

The second point about Isabella’s creepy kingdom on top of the hill is that there is no way of telling how often and for how long she was up on the Downs. For at least two years of her teens she was away at boarding school, first in London and then Heidelberg, and so unavailable for Grandstand duties. Once she returned home for good, probably in 1854, her letters make clear that, far from being marooned for weeks at a time, she moved constantly between Ormond House and the Downs. For instance, in a letter that she writes to her fiancé Sam Beeton in February 1856 she explains that she and her stepsister Jane have just got back from the Grandstand where they ‘have been doing the charitable to Granny. Poor old lady, she complained sadly it was so dull in the evening sitting all alone, so we posted up there to gossip with her.’ Another time she mentions that she has been up at the Grandstand all day ‘and of course have not sat down all day’, yet makes it clear that she is now writing from the relative calm of Ormond House. When the Grandstand was needed for a race meeting, it was Isabella who was responsible for ‘transporting that living cargo of children’ to alternative accommodation, usually a house at 72 Marine Parade in Brighton, close to the racecourse where Dorling also held the position of clerk. Far from being in permanent exile, Isabella Mayson was a body in a perpetual state of motion.

Still, whether or not Isabella was in attendance at any particular moment, it remains the case that the Grandstand made a strange kindergarten. A huge barn of a building, 50 yards long and 20 yards wide, and designed to hold 5,000 people, it was now home to perhaps no more than six little children and their minders. It has been suggested that the closest analogy would be that of living in a boarding school during the holidays. But there was an important difference. The Grandstand had never been built with children in mind. It was designed for adults and adult activity – betting, drinking, flirting, parading, coming up before the makeshift magistrate. On the one hand the world of the Dorlings and the world of Epsom racecourse were soldered together to the point where one had become a synonym for the other: or, as the Illustrated London News would put it in a few years’ time: ‘What cold punch is to turtle, mustard to roast beef, ice to Cliquot champagne, Chablis to oysters, that is Mr Dorling to the Derby.’ Yet, at the same time, there were occasions when those two worlds, the world of the bourgeois family and that of the seedy racetrack were a very awkward fit. It was this paradox that poor little Alfred Dorling, acquiring his fatal condom from among the ‘racy’ characters who hung around the Downs, had failed to understand.

Certainly we can say that the scale of the place was grand, designed to see and be seen in. As such it was a public theatre, something that older, aristocratic members of the racing fraternity found hard to grasp. The Duchess of Richmond of Goodwood wrote to Dorling about this time grandly informing him: ‘The Duchess of Richmond would prefer a portion of the Grand Stand railed off, if she could have it to Herself.’ But there was little chance of the Duchess, even with her Goodwood credentials, getting her way. The point about the Grandstand was that it belonged to the modern world and, as such, was a democratic space to which anyone could buy the right to enter. There was a huge pillared hall, a 30-yard-long saloon, four refreshment rooms, and a series of committee rooms. In 1840 when Queen Victoria had made her second and final visit to Epsom, £200 had been spent on getting the Grandstand’s wallpaper and carpets up to scratch, with the result that the Dorling children, quite literally, lived in a place that was fit for a queen. Eighteen years later when Prince Albert made a return visit, this time with his future son-in-law the German Crown Prince Frederick, the papers reported that on the receiving room wall was ‘the Royal Coat of Arms, executed in needlepoint by the Misses Dorling’. The nursery, then, was a curiously public and even ceremonial space inside which the children were expected to eat and sleep while leaving as little trace as possible of their small lives. At night they lay on truckle beds that could be folded up during the day. Whenever Henry Dorling needed to show a visiting dignitary around they could be herded into another room. At a moment’s notice all evidence of their existence could be made to disappear.

Particularly intriguing about the Grandstand set-up is the fact that the future Mrs Beeton spent formative stretches of her young life next to a commercial kitchen that catered to thousands at a time. Much has been made of Mrs Beeton’s picnic plans for forty people, or her dinner party menus for eighteen. Perhaps the fact that she lived on a Brobdingnagian scale – the eldest girl in a family of twenty-one and an amateur nursery maid in a space designed for thousands – explains the ease with which she came to think in large numbers. For this reason Dickens’ description of the Grandstand kitchens working at full pelt for the Derby is worth quoting in full.

To furnish the refreshment-saloon, the Grand Stand has in store two thousand four hundred tumblers, one thousand two hundred wineglasses, three thousand plates and dishes, and several of the most elegant vases we have seen out of the Glass Palace, decorated with artificial flowers. An exciting odour of cookery meets us in our descent. Rows of spits are turning rows of joints before blazing walls of fire. Cooks are trussing fowls; confectioners are making jellies; kitchen-maids are plucking pigeons; huge crates of boiled tongues are being garnished on dishes. One hundred and thirty legs of lamb, sixty-five saddles of lamb, and one hundred shoulders of lamb; in short, a whole flock of sixty-five lambs, have to be roasted, and dished and garnished, by the Derby Day. Twenty rounds of beef, four hundred lobsters, one hundred and fifty tongues, twenty fillets of veal, one hundred sirloins of beef, five hundred spring chickens, three hundred and fifty pigeon pies; a countless number of quartern loaves, and an incredible quantity of ham have to be cut up into sandwiches; eight hundred eggs have got to be boiled for the pigeon-pies and salads. The forests of lettuce, the acres of cress, and beds of radishes, which will have to be chopped up; the gallons of ‘dressing’ that will have to be poured out and converted into salads for the insatiable Derby Day, will be best understood by a memorandum from the chief of that department to the chef-de-cuisine, which happened, accidentally, to fall under our notice: ‘Pray don’t forget a large tub and a birch-broom for mixing the salad!’

We do not know if some of the Grandstand rooms were permanently out of bounds to the children, but certainly Amy Dorling, born in 1859 and still going strong during the Second World War, remembered playing tag around the huge public rooms, which must have echoed strangely to tiny thudding feet and shrill screams. The children might have turned feral were it not for the fact that Henry Dorling now ran his printing business from the Grandstand (yet more evidence of the fudging of interests which so alarmed hostile commentators) and visited almost daily. And then, of course, there was Granny Jerrom, that solid constant in this story who nonetheless left virtually no trace in the formal records. All we have to make her real is a family anecdote, and a recently discovered photograph.