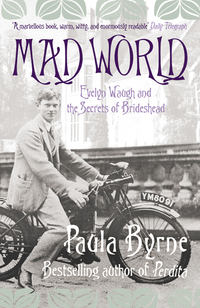

Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead

PAULA BYRNE

Mad World

Evelyn Waugh and the

Secrets of Brideshead

COPYRIGHT

Harper Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This HarperPress paperback edition published 2010

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2009

Copyright © Paula Byrne 2009

PS Section copyright © Sarah O’Reilly 2010, except ‘Other Worlds’ by Paula Byrne © Paula Byrne 2010

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

Paula Byrne asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007243778

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007455478

Version: 2016-09-22

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter 1: A Tale of Two Childhoods

Chapter 2: Lancing versus Eton

Chapter 3: Oxford: ‘… her secret none can utter’

Chapter 4: The Scarlet Woman

Chapter 5: In the Balance

Chapter 6: The Lygon Heritage

Chapter 7: Untoward Incidents

Chapter 8: Bright Young Things

Chapter 9: The Busting of Boom

Chapter 10: Madresfield Visited

Chapter 11: The Beauchamp Belles

Chapter 12: Christmas at Mad

Chapter 13: An Encounter in Rome

Chapter 14: Up the Amazon

Chapter 15: A Gothic Man

Chapter 16: Fiasco in the Arctic

Chapter 17: Ladies and Lapdogs

Chapter 18: A Year of Departures

Chapter 19: Three Weddings and a Funeral

Chapter 20: Waugh’s War

Chapter 21: The Door to Brideshead

Chapter 22: Brideshead Unlocked

Keep Reading

P.S. Ideas, interviews & features …

About the Author

The Waugh Generation: Sarah O’Reilly talks to Paula Byrne

A Writing Life

Life at a Glance

About the Book

Other Worlds by Paula Byrne

Read On

Have You Read?

If You Loved This, You Might Like …

Find Out More

Coda: ‘Laughter and the Love of Friends’

Sources

Index

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Early 1944 and Captain Evelyn Arthur St John Waugh has fallen out of love with the army. He has turned forty and is considering his options. To become a screenwriter? An overture to Alexander Korda comes to nothing. To join MI5, the intelligence service? He is turned down without an interview. Only one possibility remains: to revert to his pre-war occupation.

On 24 January he writes a letter to Colonel Ferguson, Officer Commanding, Household Cavalry Training Regiment. Copies are sent to the Secretary of State for War and to Brendan Bracken, Winston Churchill’s Minister of Information and string-puller in chief on behalf of Captain Waugh. ‘I have the honour to request,’ the letter begins, ‘that, for the understated reasons I may be granted leave of absence from duty without pay for three months.’ The understated reasons are various. That his previous service in the Royal Marines, the Commandos, the Special Services and the Special Air Service Regiment does not qualify him for his current position in a mechanised unit of the cavalry. That he no longer has the necessary physical agility for active service. That he is no good at admin, so can’t do a desk job. And that he doesn’t have the foreign languages to make him useful for the purposes of intelligence work.

Assurances are given: the novel to which he will devote his leave ‘will have no direct dealing with the war’. But expectations are dampened: ‘it is not pretended that it will have any immediate propaganda value’. The necessity of immediate action is stressed: ‘It is a peculiarity of the literary profession that, once an idea becomes fully formed in the author’s mind, it cannot be left unexploited without deterioration. If, in fact, the book is not written now it will never be written.’

Colonel Ferguson responds by ordering Waugh to go and train the Home Guard at Windsor. A less determined man than Evelyn might have capitulated and the book would never have been written. But he perseveres. By the end of January he has been granted his three months’ leave, qualified only by a commitment to a little light part-time work for the Ministry of Information. He leaves his comfortable billet in the Hyde Park Hotel and his military uniform with it.

On the morning of Tuesday 1 February 1944 he is settled in another hotel, deep in the West Country: Easton Court, Chagford, Devon – a thatched fourteenth-century farmhouse with low, dark rooms and small windows. He has been there before, in the late autumn of one of the momentous years of his life, 1931. It is a place that in his memory he cannot separate from a house and a family with which he had fallen in love that year.

In London he had regularly lain in till mid-morning. At Chagford he is up at 8.30 and at work by 10. By dinnertime on that first Tuesday, though his mind is ‘stiff’ from the tedium of army life, he has written and rewritten 1,300 words. He reports to his wife that he has made a good beginning on what he calls his ‘magnum opus’. He has ‘bought a very expensive concoction of calcium and halibut liver oil which the chemist thought would restore me to strength but on reading the label more closely I find it to be a cure for chilblains’. This may prove handy, since the lounge he has been given as a private room in which to write has a fire that smokes so badly that he has to choose between streaming eyes and frozen extremities.

By ‘close of play’ on Wednesday the score is ‘3,000 words odd’. Through the ensuing weeks he works steadily at the rate of up to 2,000 words a day, occasionally more. He revises arduously as he goes. In the end it takes him closer to five months than three, but the book that he knows in his heart he has to write is completed. The idea that had ‘become fully formed’ in his mind is ‘exploited without deterioration’.

What was that idea? The book’s original working title was ‘The Household of the Faith’. The story of a household, a family. A journey shaped by religious faith. These are its key themes. But the working title does not find its way into print. When the book is published the following year, its title page reads Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred and Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder: A Novel.

On the reverse side of that title page there is a notice to the effect that the volume has been ‘produced in complete conformity with the authorised economy standards’ of wartime publishing. You can tell that this is true when you hold a first edition in your hands and turn the coarse, rough-hewn pages.

Above the routine announcement concerning production standards, there is something more intriguing. A mysterious Author’s Note is signed ‘E. W.’, Evelyn Waugh. It reads: ‘I am not I: thou art not he or she: they are not they.’

‘I am not I’: yet Charles Ryder manifestly is Evelyn Waugh. Brideshead Revisited contains as large a dose of autobiography as Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield or Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. So who, then, was the ‘thou’ who was and was not ‘he or she’? The ‘they’ who were and were not ‘they’? What was ‘the household of the faith’ that was and was not Brideshead? What were the events that inspired the novel?

This biography sets out to find the hidden key to Waugh’s great novel, to unlock for the first time the full extent to which Brideshead encodes and subtly transforms the author’s own experiences. In so doing, it illuminates the obsessions that shaped his life: the search for an ideal family and the quest for a secure faith. The solution to the mystery can be found in that magical year of 1931. The hidden key will also unlock several of Waugh’s other major novels, including his very best one, A Handful of Dust. And it will bring us to a secret that dared not speak its name.

But we must begin with two very different childhoods. And then we must go, as Captain Charles Ryder does when he begins his recollections, to Oxford, in the years immediately after the Great War.

CHAPTER 1 A Tale of Two Childhoods

‘My name is Evelyn Waugh I go to Heath Mount school I am in the Vth Form, Our Form Master is Mr Stebbing.’

So begins his first extant literary composition, a brief self-portrait called ‘My History’, written in September 1911, at the age of seven. It is the work of a boy of strong opinions and sharp wit:

We all hate Mr Cooper, our arith master. It is the 7th day of the Winter Term which is my 4th. Today is Sunday so I am not at school. We allways have sausages for breakfast on Sundays I have been watching Lucy fry them they do look funny befor their kooked. Daddy is a Publisher he goes to Chapman and Hall office it looks a offely dull plase. I am just going to Church. Alec, my big brother has just gorn to Sherborne. The wind is blowing dreadfuly I am afraid that when I go up to Church I shall be blown away. I was not blown away after all.

The child, William Wordsworth once said, is father to the man. Here is Evelyn Waugh the writer in embryo: a good hater of bad masters, a spectator of the world who can make ordinary things (like sausages) look funny. He is just going to church: eventually he will be blown in the direction of Rome. His household is comfortably middle class: prep school, domestic servants (Lucy in the kitchen with sausages), the home dominated by Daddy, with his important-sounding job (Publisher) in his dull London office. And a big brother who has just gone to a big, renowned public school: Sherborne. Some years later, an ill wind will blow dreadfully from there, redirecting Evelyn to another school.

Mother is not mentioned in this first little sketch. But Evelyn was closer to her than he was to his father, chiefly because Arthur Waugh, managing director of the publisher Chapman and Hall, idolised his first-born son Alec to an absurd degree. Albeit with good intentions: Arthur was determined not to be like his own father, a sadistic bully who rejoiced in the nickname ‘The Brute’. Arthur, educated at Sherborne School and then New College, Oxford, had married Catherine Raban, a gentle girl from an English colonial family originally hailing from Staffordshire, in 1893. Their first child, Alexander (‘Alec’) was born in 1898. Arthur called him ‘the son of my soul’ and, as the boy grew, developed a relationship with him that was intense, exclusive and all consuming.

Evelyn was born on 28 October 1903 at the family home in Hampstead. When Evelyn was four and the family moved to a larger house, closer to Golders Green, Alec left for boarding school. This might have been the moment when the younger son could have come out from under the wing of Mother and Nurse. But he didn’t. Evelyn’s relationship with his father always remained difficult. There is already a hint of irreverence in that early sketch, with its dismissal of Chapman and Hall’s offices as ‘a offely dull plase’. Evelyn would grow into a rebellious teenager who carefully cultivated a satirical, worldly, disengaged persona, not least in order to set himself against what he perceived to be his father’s nauseating sentimentality and histrionic tendencies.

Arthur Waugh, who was very well respected and connected in the London literary world, had the tastes of his age and class: Shakespeare, the King James Bible, Dickens and cricket (this was the era of the legendary Dr W. G. Grace). The Dickens copyright was the jewel in Chapman and Hall’s crown. Arthur Waugh was rotund, diminutive, with twinkling eyes and candyfloss white hair. Ellen Terry, the greatest actress of the age, had the perfect name for him: ‘that dear little Mr Pickwick’.

In such a literary household, it was probably inevitable that Evelyn should grow up literary – or at the very least that he should view his own family through the filter of books and plays. Arthur Waugh seemed to spend all his time acting out roles. When he greeted visitors, he was the over-hearty Mr Hardcastle of Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer. In deploring the ingratitude of his sons, he was Shakespeare’s King Lear. Above all, he was Mr Pooter in George and Weedon Grossmith’s Diary of a Nobody. ‘Why, I am Lupin!’ Evelyn cried out delightedly when he first read the book, identifying instantly with Pooter’s rebellious, loutish and troublesome son. It remained a favourite book, which he regarded as the funniest in the English language. The hilarious clashes in values and attitude between the respectable lower-middle-class civil servant Pooter and his reckless, extravagant son mirrored to a tee Evelyn’s sense of his own disjointedness from his father. It is no coincidence that in Brideshead Revisited Lady Marchmain reads Diary of a Nobody aloud to lighten the tension generated by her son Sebastian’s drunken behaviour at dinner.

Evelyn later displayed his father’s gift for adopting theatrical roles, particularly in his middle age when the part that he cast for himself was, as he put it in his autobiographical novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, ‘that of the eccentric don and testy colonel’: ‘he acted it strenuously, before his children … and his cronies in London, until it came to dominate his whole outward personality’.

Arthur Waugh would have been delighted by Ellen Terry’s Pickwick comparison. He often read Dickens aloud in his marvellously theatrical voice. Though Evelyn, ever the Lupin, affected to despise his father’s theatricality (‘his sighs would have carried to the back of the gallery at Drury Lane’), he also later acknowledged Arthur’s verbal gifts: ‘he read aloud with a precision of tone, authority and variety that I have heard excelled only by John Gielgud’. Had Evelyn lived to witness the celebrated 1981 Granada Television adaptation of Brideshead, he would have found it fitting that Gielgud stole the show with his performance in the role of Charles Ryder’s father. Arthur kept Evelyn and his friends enthralled with his readings of Dickens and Shakespeare and his favourite poets. In the autobiography A Little Learning Evelyn wrote of how his father’s love of English prose and verse ‘saturated my young mind, so that I never thought of English Literature as a school subject … but as a source of natural joy’.

The account of Waugh’s happy childhood in A Little Learning belies the common view that he was deeply ashamed of his middle-class, suburban upbringing. He paints a delightful picture of the pleasures of life at Underhill, the family home on the edge of Hampstead Heath. He felt lucky to be at a day school and not to be sent away to board: ‘it was a world of privacy and love very unlike the bleak dormitories to which most boys of my age and kind were condemned’.

He viewed Hampstead as something like an eighteenth-century pleasure garden. He loved the thrice-yearly fair, with its aromas of ‘orange-peel, sweat, beer, coconut, trampled grass, horses’ and the rowdy crowd of ‘costers’ from the East End of London, kitted out in pearl-buttoned caps and suits. Feared by some, they were creatures of fascination to the young boy who saw in them a ‘kind of Pentecostal exuberance which communicated nothing but goodwill’. It did not seem to matter that father was forever preoccupied with Alec’s triumphant exploits down in Dorset on the playing fields of Sherborne.

At the centre of this small boy’s ‘paradisal’ world were ‘two adored deities’: his mother and his nurse, Lucy. Mother was associated with ‘earthy wash-leather gloves and baskets of globe artichokes and black and red currants’. Lucy was a devout Christian, ‘strictly chapel’, who loved him unconditionally and was ‘never cross or neglectful’.

Equally adored was a trio of maiden aunts who lived at Midsomer Norton in Somerset. When visiting in the summer holidays, Evelyn nosed around their house. It was stuffed with Victoriana: cabinets of curiosities, fans, snuff boxes, nuts, old coins and medals. The smell of gas, fruit, oil and leather. The aunts’ life was like something out of the previous century, locked in aspic. A whirl of church bazaars, private theatricals, picnics and games, ‘the place captivated my imagination as my true home never did’.

‘Save for a few pale shadows’ – as, for example, when he almost choked to death on the yolk of a hard-boiled egg – Evelyn’s childhood was bathed, he claimed, in ‘an even glow of pure happiness’. Like nearly all literary recollections of times past, A Little Learning offers up the image of childhood as a paradise lost, an Eden from which the author has been expelled, a secret garden glimpsed through a door in the wall, an alternative world like the one into which the child tumbles in one of Evelyn’s favourite books, Alice in Wonderland. This theme of exile and exclusion from Arcadia would preoccupy him throughout his life and his work. He always felt as if he did not quite belong. That was what fired his imagination and his comic vision. Whether writing about a deranged provincial boarding school, or the exploits of London’s Bright Young Things, or the old Anglo-Catholic aristocracy, he was always the outsider looking in.

His sense of displacement from his own family was there from the start, despite all the genuine memories of a happy and stable early childhood. In later years he was never close to his parents and his brother. With Alec away at boarding school, he was drawn to other families. When Evelyn was six he watched three children, two girls and a boy his own age, playing in a nearby street. He befriended the family. In his autobiography he calls them the Rolands. They were actually called Fleming and they became the first of his substitute families, and remained so for more than a decade.

The children built themselves a fort and formed a gang called The Pistol Troop. They endured tests of courage, walking barefoot through stinging nettles, climbing dangerously high trees and signing their names in blood. Evelyn threw himself into these boisterous games. He was as physically brave as a young boy as he would be when a traveller and a soldier in later years.

The children also devised their own magazine and put on amateur dramatics, writing and acting in their own short plays. The magazine, containing one of Evelyn’s first stories, was typed and handsomely bound. So began his lifelong obsession with fine bindings. Whenever he finished writing a novel, he had the manuscript expensively bound, and most of his works were produced in not only a mass-market printing but also a beautiful hand-bound limited edition for presentation to friends.

Mrs Fleming thought that Evelyn was an only child, until she was put right by one of her own children: ‘Oh, but he isn’t, he has a brother at school whom he hates.’ He did not hate Alec. Rather, he accepted with seeming equanimity that the five years that separated him from his brother made ‘in childhood, a complete barrier’. Having no sister, he was drawn to female friends and held girls in high regard.

After an appendix operation at the age of nine, he spent time convalescing with a family called Talbot who lived near the Thames Estuary. He was drawn to their stuff – a banjo, old photograph albums, a phonograph, china vases and great coats – but it was the family that really captured his affections: ‘the household was extraordinarily Dickensian, an old new world to me. I was very happy there, so happy that I neglected to write home and received a letter of rebuke from my father … I returned home and this glimpse of another world was occluded.’

From this time on, he would always be drawn to glimpsed other worlds and large, seemingly happy families. The Talbots were not rich or grand. Far from it: the money they received for Evelyn’s board and lodging was used to release furniture from the local pawnshop. The father, an unemployed old sailor, was mildly drunk every night, but he was a jolly drunk. He built the children a makeshift tree house. It was there that Evelyn and the eldest Talbot girl, Muriel, exposed their private parts to each other.

Despite the idealisation of other families, the impression persists of Evelyn as a happy boy in the ‘lustrum between pram and prep school’, collecting microscopes and air-guns, squirrelling away ‘coins, stamps, fossils, butterflies, beetles, seaweed, wild flowers’. Like most boys he went through obsessive phases, one year with his chemistry set, another with magic tricks. He was drawn to dexterity, observing the local chemist melting wax to seal paper packages and the Hampstead shopkeepers working deftly with weights and scales, shovels and canisters, paper and string: ‘Always from my earliest memories I delighted in watching things well done.’

Years later, when his Oxford friend Henry Yorke took him to his family’s factory in Birmingham, he was able to appreciate the aesthetic beauty of the industrial plant, recording in his diary how impressed he was by the ‘manual dexterity of the workers … The brass casting peculiarly beautiful: green molten metal from a red cauldron.’ This is not to say that he was drawn to the white heat of a technological future. The manual dexterity of those workers was, he said, ‘nothing in the least like mass labour or mechanisation’. Rather, it was ‘pure arts and crafts’. His delight in watching things well done was bound up with a sense of custom and tradition. As he admits in A Little Learning, he was in love with the past. He longed for the loan of a Time Machine. Not to take him to the future (‘dreariest of prospects’), in the manner of H. G. Wells, whose The Time Machine was published just a few years before he was born, but rather ‘to hover gently back through the centuries’. To go back into the past ‘would be the most exquisite pleasure of which I can conceive’.

If the adult Evelyn had travelled on his Time Machine back to the childhood of one of the aristocrats who would become his Oxford contemporaries, he would have found – and been pleased to find – that little had altered over the years. Hugh Lygon and his siblings were typical products of a system that had endured for generations. For the boys, prep school, Eton and Oxford; for the girls, very little in the way of formal education – a governess who taught in the schoolroom at home and the use of a well-stocked library were deemed to suffice.