Marching to the Mountaintop: How Poverty, Labor Fights and Civil Rights Set the Stage for Martin Luther King Jr's Final Hours

“We shall overcome. We shall overcome.

We shall overcome some day-ay-ay-ay-ay.

Deep in my heart, I do believe,

We shall overcome some day.”

Freedom song adapted from a gospel hymn for a southern labor fight during the 1940s

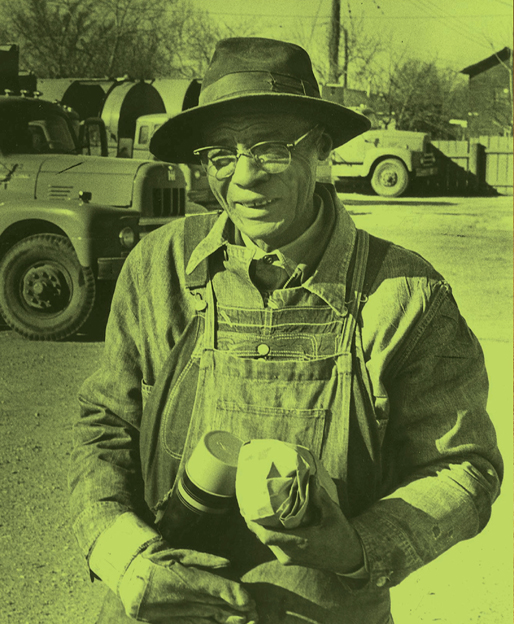

In 1968 many Memphis residents stored their trash in uncovered 50-gallon drums. Frequent rains added to the soupy, unsavory nature of the garbage that workers transferred to waiting trucks. The exclusively African-American workforce took its orders from white supervisors (above).

Unbeknownst to Mrs. C. E. Hinson, another man was already trapped inside the vibrating truck body. Before vehicle driver Willie Crain could react, Echol Cole, age 36, and Robert Walker, age 30, would be crushed to death. Nobody ever identified which one came close to escaping.

Cole and Walker wore raincoats for good reason on February 1, 1968. At the end of a wet workday, Willie Crain’s four-man crew had divvied up the truck’s available shelter for the trip to the garbage dump. Elester Gregory and Eddie Ross, Jr., squeezed into the driver’s cab with Crain and left the younger members of the crew with two choices. They could hold on tight to exterior perches while the truck passed through torrential rains. Or they could climb inside the truck’s garbage barrel, wedged between the front wall of the vessel and the packing arm that pressed a load of refuse against the rear of the truck. Walker and Cole opted for the dryer and seemingly more secure interior space.

Rain or shine, the 1,100 sanitation workers of Memphis collected what amounted to 2,500 tons of garbage a day. This all-male, exclusively African-American staff worked six days a week with one 15-minute break for lunch and no routine access to bathroom facilities. Their pay was based on their garbage routes, not their hours worked, so there was no overtime compensation when the days ran long. Workers supplied their own clothing and gloves, toted rain-saturated garbage in leaky tubs supplied by the city, and had no place to shower or to change out of soiled clothes before returning home. Even though the men worked full-time, their earnings failed to lift their families from poverty. To make ends meet, many found extra jobs, paid for groceries with government-sponsored food stamps, lived in low-income housing projects, and made use of items scavenged during their garbage runs.

The men toiled under a system with eerie echoes of the pre–Civil War South, what some called the plantation mentality. Whites worked as supervisors. Blacks, who made up almost 40 percent of the city’s population, performed the backbreaking labor. Bosses expected to be addressed as “sir.” Workers endured being called “boy,” regardless of their ages. Whites presumed to know what was best for “our Negroes,” and blacks tolerated poor treatment for fear of losing their jobs, or worse. City officials had no motivation to recognize the fledgling labor union that sought to protect the workers and to advocate for their rights. As a result, employees “acted like they were working on a plantation, doing what the master said,” recalled sanitation worker Clinton Burrows.

Memphis residents, or Memphians, called their sanitation workers garbagemen, walking buzzards, and tub toters, a name that reflected the washtubs they used for ferrying garbage from backyard storage barrels to city trucks. Workers (above, R. J. Sanders) balanced the large tubs on their heads or pushed them in three-wheeled carts.

Garbage collectors faced back injuries and other strains because of the physical demands of the work, and they fretted about the use of unsafe equipment. Willie Crain’s truck had been purchased on the cheap in 1957 at a time when Henry Loeb ran the department of public works. By 1968, when Loeb returned to public office as the newly elected Memphis mayor, the city had begun replacing the old trucks. Two of the vehicles, including Crain’s truck, had been retrofitted with a makeshift motor after the unit’s trash-compacting engine had worn out. As best as anyone could figure after the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, a loose shovel had fallen into the wiring for the replacement motor and had accidentally triggered the reversal of the trash compactor.

Like those of other sanitation workers, the families of Cole and Walker managed paycheck to paycheck, leaving no reserves for emergencies. Their jobs came without the benefits of life insurance or a guarantee of support in the case of work-related injury or death. Mayor Loeb honored the victims by lowering public flags to half-mast, but he offered scant assistance to their survivors. The city contributed $500 toward the men’s $900 funerals and paid out an extra month’s wages to Cole’s widow and the widow of Walker (who was pregnant).

The deaths of Cole and Walker wrapped up a particularly bad week for African Americans employed at the department of public works. This unit handled garbage collection, street repairs, and other city maintenance. On January 30, two days before the sanitation-worker fatalities, 21 members of the sewer and drainage division had been sent home with only two hours of “show-up pay” because of bad weather. The previous public works director had kept staff employed regardless of the weather, but Mayor Loeb had ordered Charles Blackburn, his new director, to return to Loeb’s old rainy-day policy from the 1950s. In a climate where rain fell frequently, workers lost their ability to predict their income. “That’s when we commenced starving,” explained road worker Ed Gillis.

Street workers turned to Thomas Oliver Jones for help. T. O. Jones was among 33 sanitation workers who had started a strike in 1963 and lost their jobs. When officials were pressured to rehire the workers, Jones refused to rejoin the force. Over time he established a fledgling union for public works employees and gained recognition for his small group by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, better known as AFSCME. Jones’s group called itself Local 1733 in honor of the 33 men fired during the 1963 strike. Jones tried to lead another walkout in 1966. This time 500 workers agreed to strike, but the work stoppage collapsed after a local judge declared the strike illegal. “All city employees may not strike for any purpose whatsoever,” the judge declared. This injunction, or prohibition against striking, had never been challenged in court, so it remained in force and discouraged further strikes. Nonetheless, Jones continued to quietly recruit members for Local 1733 and became its unofficial spokesperson.

“THERE wasn’t too much opportunity for a black man at that time. Really wasn’t no other jobs hardly to be found. I was at a point I had to take what I could get.”

Taylor Rogers, who became a Memphis sanitation worker about 1959

Jones raised the men’s rainy-day concerns with Charles Blackburn and left the meeting thinking the public works director had agreed to pay the 21 men their missing wages. Blackburn said he would reconsider the rainy-day policy, too, and, within a few days, he instructed supervisors to try to keep everyone fully employed regardless of the weather. During that same period, Panfilo Julius Ciampa, field director for Washington, D.C.-based AFSCME, visited Memphis. Jones arranged for his union contact to meet the new public works director on February 1. P. J. Ciampa learned that Blackburn was a personal friend of the newly elected mayor and had gained appointment to the job after an unrelated career in insurance work. He would later describe Blackburn as “a guy who didn’t know a sanitation truck from a wheelbarrow.”

By 1968 the city of Memphis had replaced most of its garbage trucks with a rear-loading model (above, carrying unidentified workers). Echol Cole and Robert Walker died in an older side-loading vehicle nicknamed the wiener barrel because of its rounded shape. Their fatalities followed the deaths of two other sanitation workers during a 1964 truck rollover accident.

The men toiled under a system with eerie echoes of the pre–Civil War South, what some called the plantation mentality. Whites worked as supervisors. Blacks performed the backbreaking labor.

Their afternoon meeting took place shortly before

Willie Crain’s truck began crushing two sanitation workers to death. Jones learned of the accident almost immediately. As he drove back from taking Ciampa to the Memphis airport, Jones followed a hunch that trouble was brewing and pursued an emergency public works vehicle that turned out to be racing toward the reported accident. Events snowballed as the news spread. Surviving workers knew they could just as easily have lost their own lives. They grew offended when the city didn’t cover the full costs of burying the victims. They fretted over the potential for lost wages during bad weather. They worried about how to survive on the money they earned even at full employment. And they fumed when the 21 workers opened their pay envelopes the following week and discovered no boost in pay for the rainy day of January 30.

Something snapped—or perhaps ignited—under the weight of these pressures in a system run with that plantation-style mind-set. In theory, slavery had ended 100 years earlier, but blacks in Memphis during 1968 had more in common with African-American slaves who had worked the region’s cotton fields than with the whites who ran Memphis businesses, served in city government, and covered the local news. Even poor whites, thanks to decades of segregated southern living, focused more attention on their racial superiority over blacks than the common interests they and blacks could have pursued through unions for higher wages and better working conditions. Poverty, racial isolation, and a history of voter intimidation left blacks underrepresented and their needs ignored.

“Nobody listens” to black people, observed Maxine Smith, executive director of the Memphis branch of the NAACP. “Nobody listened to us and the garbage men through the years. For some reason, our city government demands a crisis” before noticing African-American concerns.

Whites may not have seen it coming, but a crisis of epic proportions loomed on the horizon for Memphis, Tennessee.

Chapter 2

STRIKE!

“I’m ready to go to jail,” announced union organizer T. O. Jones.

“Why are you going to jail?” asked Charles Blackburn.

Jones, having excused himself to change into khaki pants—jail clothes—reminded the new public works director of the court injunction that prohibited strikes by Memphis public workers. Blackburn had offered no resolution of the list of demands Jones had just shared with him, demands that he had developed earlier that evening during a meeting with more than 700 department workers. Key principles included union recognition, pay increases, overtime compensation, full employment regardless of weather, and improved worker safety. Now Jones knew the men would strike.

“Oh, workers can you stand it? Oh, tell me how you can.

Will you be a lousy scab, or will you be a man?

Which side are you on, oh, which side are you on?

Which side are you on, oh, which side are you on?”

Verse from a labor song written in 1932 by Florence Patton Reece, a coal miner’s wife

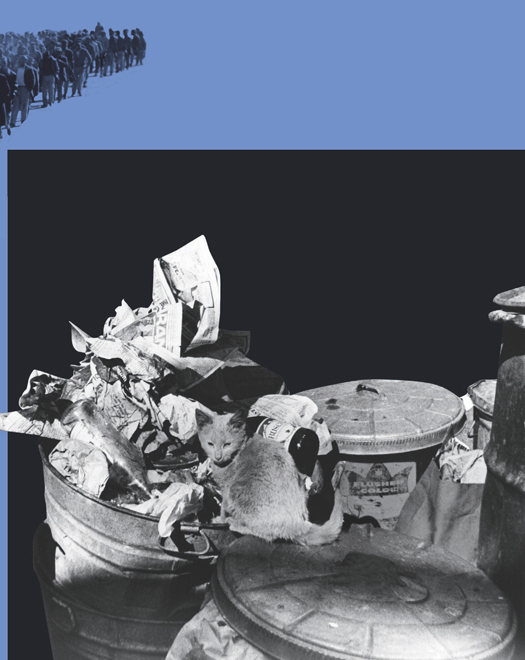

Among the ways mayor Henry Loeb (above, walking with striking workers to their February 13 meeting) offended blacks was to mispronounce Negro, the era’s term for African Americans, as the racism-laced Nigra. In 1968 blacks refused to contribute their garbage for collection by strike-breaking workers. Uncollected, the waste accumulated by the week (above).

“He gives us nothing, we’ll give him nothing,” yelled one of the men when waiting workers learned of Blackburn’s stance. Those gathered held no official vote on whether or not to strike; they just reached a collective agreement to quit working. Maybe city officials would take notice if the garbage stopped being picked up and road repairs ceased.

The next morning, empty work barns must have erased whatever illusions Blackburn held about the submissiveness of his workforce. Only 170 of the city’s 1,100 garbage workers reported for duty on Monday, February 12. Just 16 members of the 230-man street crew appeared. Almost without warning, more than 85 percent of the workforce had failed to show up for work. The numbers were even worse the next day. Some workers had reported on Monday because they hadn’t heard about the strike. Now they joined the walkout, too. Peer pressure kept others off the job. If employees kept working, they knew they’d hear about it back in the neighborhoods and churches they shared with the strikers. Better to stay home. Hundreds of enthusiastic men rushed to join the union.

Public Works Director Blackburn struggled to organize his skeletal workforce into the five-man crews required to run a garbage truck. On Monday he managed to staff 38 garbage trucks, leaving as many as 150 vehicles idle for the day. By Wednesday he could fill only four. Every truck required a police escort in order to ensure that striking workers wouldn’t harass those few men who had stayed on the job.

P. J. Ciampa groaned at his AFSCME office on Monday when he learned of the Memphis walkout. This veteran organizer of countless labor strikes knew the Memphis timing was all wrong. Garbage strikes worked best in hot weather when garbage smelled its worst. Plus, city leaders would find it easy in February to hire unemployed agricultural workers to break the strike. And how were workers going to feed their families when their paychecks stopped coming? Usually union dues supported a strike fund, but Local 1733’s small membership base had created few assets. Furthermore, because southern business leaders and politicians disliked unions, the South was the hardest place to win a strike. On top of it all, in the face of an unexpected strike, public support would probably favor the newly elected leaders of Memphis. Never strike in anger, AFSCME officials always advised, and strike only when victory is certain. The Memphis strike looked like a disaster.

Holes peppered the corroded bottoms of many city-supplied washtubs, so garbage slop dripped onto the bodies and clothes of sanitation workers as they toiled. Tubs rested unused (above) during the 1968 strike. The Memphis action began just as a nine-day garbage strike ended in New York City (above, sweeping up some accumulated trash).

Tell the men to go back to work, Ciampa told Memphis labor leader Bill Ross by telephone. Ross refused, explaining that he had never seen such a determined group of men. “I said, buddy, I’m the only one white man in this building with 1,300 black souls out there. I’m not about to go out there and tell those people to go back to work. Now if you want to tell them to go back to work, you come down here and you do it yourself.”

Almost immediately the AFSCME field director flew to Memphis. By Monday night, three other AFSCME staffers had arrived, including Bill Lucy, a black Memphis native pulled from an assignment in Michigan. After meeting on Tuesday with Mayor Henry Loeb and with a room full of striking workers, Ciampa realized that nobody, not even T. O. Jones, could have stopped the strike. Jones “had to run to stay out front,” Ciampa would later say.

Ciampa could find no common ground with the mayor. Loeb insisted that negotiations take place in front of news reporters, a tough environment for reaching the compromises necessary for strike settlements. Ciampa sized up Loeb as insincere, close-minded, and happy to make comments that played well to his white citizen base while avoiding serious negotiation. Meanwhile, Ciampa, a tough-talking negotiator with an Italian-American accent, struck Loeb as rude and intrusive, and Ciampa’s assertive northeastern style grated against other whites, too. After Ciampa directed a few choice comments at the mayor—“Oh, put your halo in your pocket and let’s get realistic”; “Because you are mayor of Memphis it doesn’t make you God”; and “Keep your big mouth shut!”—orange bumper stickers reading “Ciampa Go Home” appeared all over Memphis. Within days AFSCME international director Jerry Wurf would decide to take personal charge of the negotiations, leaving Ciampa to coordinate strategy regarding the workers.

Traditionally, striking workers would set up picket lines and march with protest signs at their places of work. Replacement laborers, known as scab workers, would have to “cross the picket lines” and face verbal harassment by strikers in order to get to work. But Ciampa’s team and local union leaders worried that this aggressive approach might backfire in the racially charged South. They didn’t want to give members of the city’s almost entirely white police force an excuse to attack black strikers. Instead, strike organizers turned to tried-and-true forms of nonviolent civil disobedience: mass meetings, peaceful marches, boycotts, and so on. Such strategies had worked in past labor fights and were central to the ongoing civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King, Jr.

“WE’VE got to stay together in the union to win the victory. Strength is in numbers. We must stay together for however long is necessary—a day, a week, a month.”

P. J. Ciampa, AFSCME field director, addressing workers on February 13, 1968

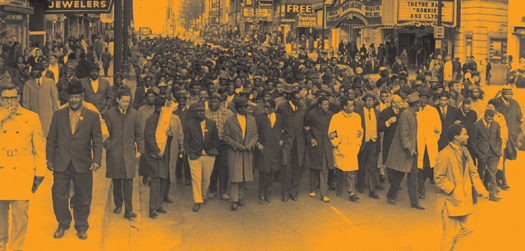

The first mass march occurred the afternoon of Tuesday, February 13, day two of the strike. T. O. Jones and Bill Lucy led a formation of more than 800 workers, walking in rows of four or five men, from their union meeting place in north Memphis to downtown. They clapped, cheered, and sang freedom songs as they marched a distance of about five miles to city hall. “The men are here,” Lucy told the mayor. “You said, ‘Any men you want to bring down to talk to me, I’ll talk to them.’ Here they are.” At first Loeb misunderstood the size of Lucy’s group and asked him to escort the men into the mayor’s office. Soon he corrected himself and met workers in a large assembly hall.

Loeb’s so-called plantation-mentality approach backfired when he spoke to the workers as if they were children—humoring, scolding, and pressuring them to return to work. To the mayor’s shock, the men laughed at him.

Strike organizers credited Henry Loeb (above, at desk, during early negotiations) with becoming their best ally because his attitudes and behavior united blacks (below, marching on February 23) in their opposition to the city.

They clapped, cheered, and sang freedom songs as they marched a distance of about five miles to city hall. “The men are here,” Lucy told the mayor. “You said, ‘Any men you want to bring down to talk to me, I’ll talk to them.’ Here they are.”

When Loeb expressed his empathy for them by using the expression, “I’d give you the shirt off my back,” one of the men called in reply, “Just give me a decent salary, and I’ll buy my own.” The workers’ cheekiness and disrespect infuriated the mayor. Loeb vowed to get the garbage collected with or without the men’s help. “Bet on it!” he declared as he stormed out of the meeting.

Loeb was a well-educated business-owner-turned-politician. Three generations of his family had exploited black workers and amassed a fortune in the family laundry business. His father had prevented black washerwomen from organizing a union or striking for better pay by filling their jobs from the ranks of the unemployed. Employees put up with miserable wages because some job was better than no job. When Henry Loeb became public works director in the 1950s, he brought along his family business mind-set. As director he bought the cheapest of equipment, instituted the program of staff cuts on rainy days, justified unpaid overtime by offering paid vacation, and beat back every attempt to form unions. For Henry Loeb, the 1968 strike became a battle of wills—mayor against rebellious blacks. If he just held out long enough, he believed, the workers would give up. Early in the strike, Loeb told a white acquaintance and union advocate that his father “would turn over in his grave if he knew he had ever recognized a damn union,” Taylor Blair recalled. “I knew there wasn’t much point in arguing with a fellow like that because he was trying to uphold what his daddy had said.”

“THIS IS just a warning. Please don’t bring another damn truck out of that gate. Do you love your family? Please, please.”

Anonymous note sent by a strike supporter to a worker who continued to collect garbage

Loeb suspended settlement negotiations soon after his first meeting with the workers, and he announced that the city would begin replacing workers two days later. To poll the striking workers, union officials asked them to stand if they wanted to keep fighting. “They stood in unison—1,000 plus. They’re not going back,” an AFSCME official reported. By Friday Loeb had recruited replacements for only a fraction of the missing workers. Most whites dismissed garbage collection as beneath them, and only the most desperate of African Americans agreed to work against the cause of fellow blacks.

The city developed emergency rules to cope with the labor shortage. Trash collection dropped from twice to once a week. City officials instructed citizens to haul their trash to the curb. They encouraged families to include food waste in their trash—left uncollected it would encourage breeding of the city’s persistent population of rats—but to store other trash until the strike ended. Burning garbage remained illegal. Boy Scout groups volunteered to carry garbage barrels to curbs for the elderly, or even to haul trash to emergency dump sites. Others earned cash from such chores.

Members of the city council struggled to find their roles in the growing crisis. Like the mayor, they were new to their jobs and to a weeks-old governance system. The mayor insisted that he alone could negotiate on behalf of the city, and he became angry whenever council members tried to settle the strike. The ten whites on the council (including the council’s sole female member) saw little reason to challenge his authority, and the three blacks on the council lacked the political power to argue otherwise.

After the strike carried on into a second week, though, black councillor Fred Davis, chair of the city’s public works committee, offered to meet with workers to discuss their grievances. The February 22 session deteriorated after union reps recruited hundreds of workers to march on city hall and crowd the council chamber. Volunteers arrived with more than 100 loaves of bread, and wives of striking workers made bologna sandwiches for the group. Workers applauded as union reps and supportive ministers spoke forcefully on their behalf, and they refused to leave without having their demands met. Committee members struggled to construct a settlement resolution that could be presented to the full council for approval the next day. It took more than an hour to persuade T. O. Jones and the men to accept the one-day delay.