Shackles From the Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy

Credit 1

Credit 2-3

Copyright © 2017

Michael H. Cottman

Compilation copyright © 2017

National Geographic Partners,

LLC

All rights reserved.

Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 12,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. The Society receives funds from National Geographic Partners LLC, funded in part by your purchase. A portion of the proceeds from this book supports this vital work. To learn more, visit www.natgeo.com/info.

For more information, visit nationalgeographic.com, call

1-800-647-5463, or write to the following address:

National Geographic Partners

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688

U.S.A.

Visit us online at nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers: ngchildrensbooks.org

More for kids from National Geographic:

kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary

Rights: bookrights@natgeo.com

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Designed by James Hiscott, Jr.

Hardcover ISBN 9781426326639

Ebook ISBN 9781426326677

Reinforced library binding ISBN: 978-1-4263-2664-6

v4.1

a

Version: 2017-07-05

DEDICATION

For my daughter, Ariane

We have hurdled waves together in the Pacific Ocean, snorkeled in the Gulf of Mexico, smiled at parrotfish in the Caribbean Sea, and talked about life along the Chesapeake Bay. What wonderful father-daughter memories. Embrace your sense of adventure and continue to explore the world’s magnificent waterways, where you will always find peace. You are a blessing. Love, Dad.

A NOTE ABOUT LANGUAGE

As you retrace the route of the Henrietta Marie slave ship, the journey to faraway ports of call will also reveal an unpleasant side of history: Racial epithets spoken by slave traders to identify enslaved African people were uncovered in historical records and are presented in quotations. In the pages of this book, we offer an uncensored and sometimes uncomfortable portrayal of slavery in the 17th century to educate and enlighten young readers.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

A Note About Language

Foreword

Timeline of the Henrietta Marie

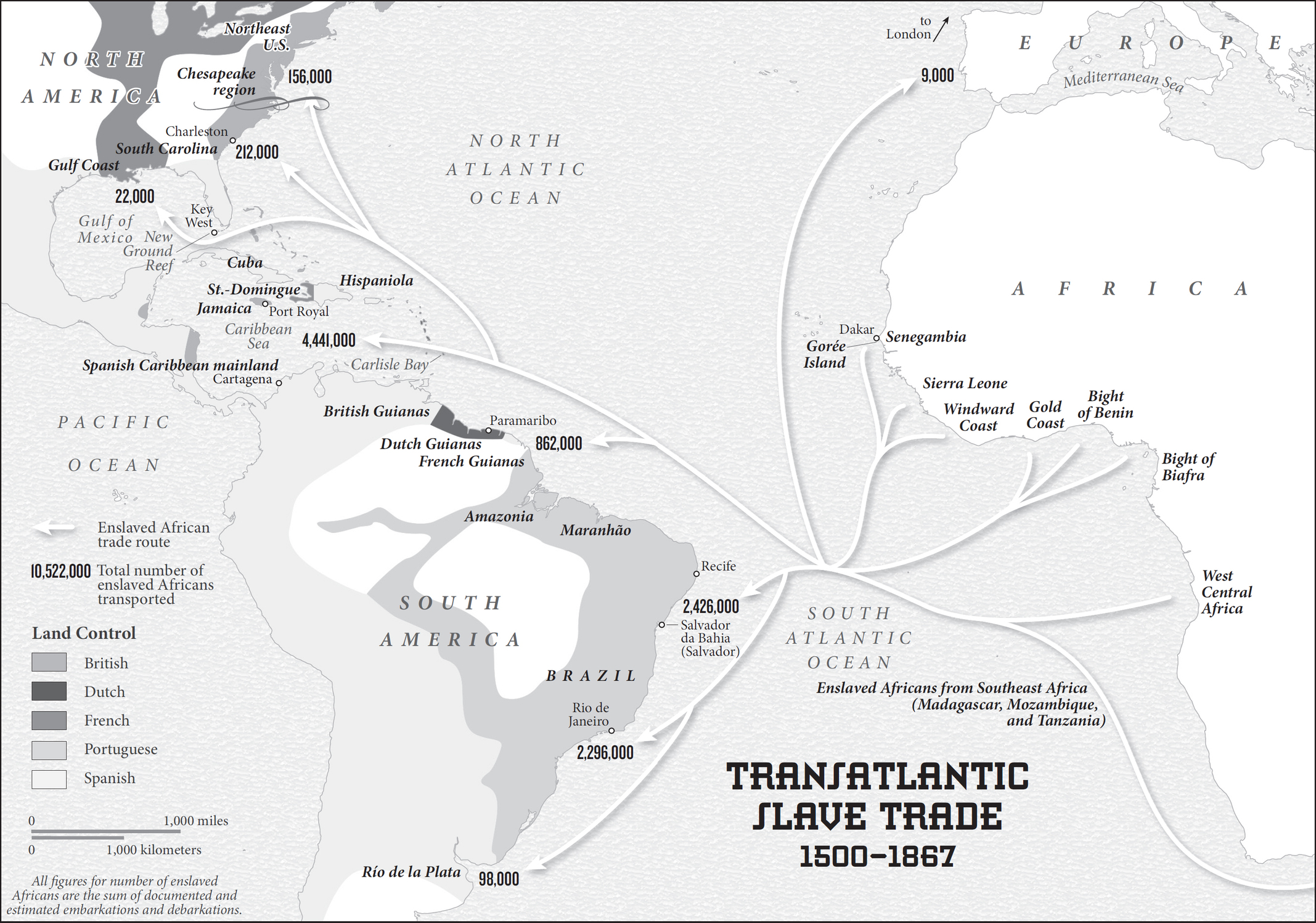

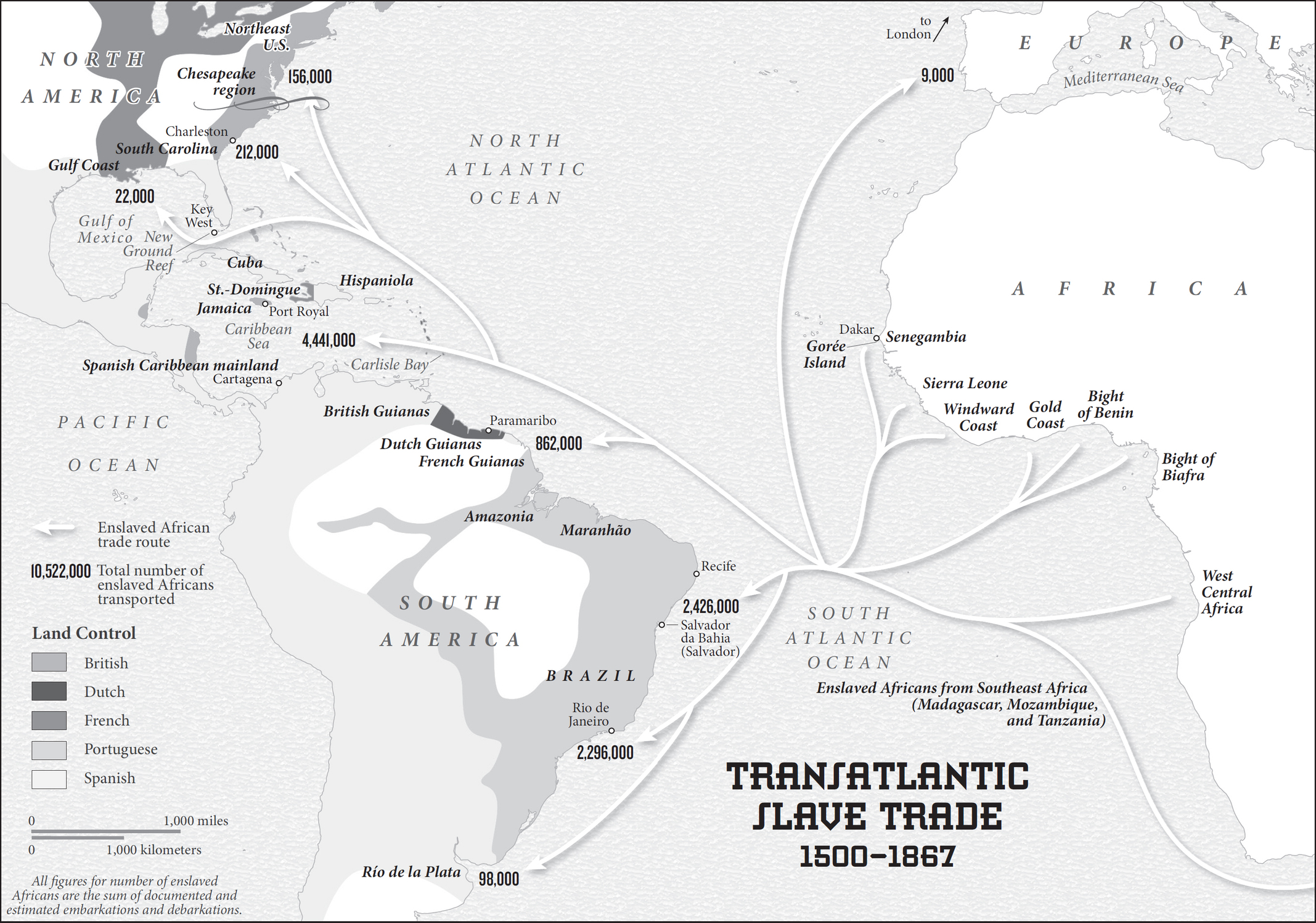

Map of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Epilogue: Voyage to Discovery

Further Reading & Other Resources

Acknowledgments & Photo Credits

FOREWORD

by Geoffrey Canada ∼ president of the Harlem Children’s Zone

THESE DAYS, when people talk about slavery in the United States, they think of it as ancient history, but for me it’s not so distant. That’s because I have spoken face-to-face with a slave, my great-grandmother.

She was born just a couple of years before the Emancipation Proclamation, so while she grew up free, she was born into slavery. I only learned about it years after her death, and I was stunned. Suddenly slavery was very real to me. Then something else happened and made me realize slavery is a legacy that’s part of who I am today.

For a segment on the PBS television show Finding Your Roots, historian and Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and his staff did a thorough search of my genetic makeup and my family history. My father had left our family when I was very young, so I had a lot of unanswered questions about my last name and genealogy. Like the characters in the comic books I loved as a young boy, I also wanted to know my “origin story,” to learn what I was made of, what slice of the African-American experience I read about in school was my own. What Gates uncovered was astounding to me.

The researchers dug into old records to see where my father’s surname and family had come from. After some twists and turns, they were finally able to trace the family back to the slave operations of a rural plantation in Virginia run by the Cannady family.

I traveled with Gates to the area where my ancestors were held as slaves. It was disturbing to think of my own flesh and blood living there, people like my great-grandmother, unable to read or write or even know where they were in this strange foreign place. As I walked through the land, surrounded by hills and hearing dogs barking in the distance, I felt in my gut how trapped and frightened my ancestors might have felt there. Even though I now know where my ancestors lived during slavery, I still have so many questions: How long were they there? How were they treated? Did they sail across the Atlantic on a ship like the Henrietta Marie? Sadly that ancestry is untraceable for so many African Americans, who lost their history along with their freedom and dignity.

For me, discovering my own family story highlighted the closeness of history—and that our collective history helps shape us into who we are today.

The Emancipation Proclamation ended the practice of slavery more than 150 years ago, but the tragic legacy of those prior decades continues to cast a long shadow over our present.

Like author Michael Cottman, and the intrepid treasure hunters and marine archaeologists unearthing the wreck of the Henrietta Marie under the sea, it’s critical for all of us to investigate the past—to learn what ground we stand on as we step forward into the future.

TIMELINE OF THE HENRIETTA MARIE

PROLOGUE

“WHERE IS YOUR VILLAGE?” the young girl asked me. It was 1997 and I was traveling through Timbuktu, which is a city in the country of Mali in West Africa.

While there, I met this girl, 10 years old, with brown skin and tiny earrings. She lived on the banks of the Niger River.

She was curious about me. She probably noticed my unusual clothes and correctly concluded that I wasn’t from there.

“I’m from Detroit, in the United States,” I told her.

She paused, then told me that she came from a family of kings and queens, that the men in her tribe were the village elders, and that the women taught young girls to read and write.

“Who are your people?” she asked.

This time I paused. I didn’t really have an answer to her question. I told her about a slave ship called the Henrietta Marie and how I was led to Africa because of this ship. And I told her that we’re all connected through the spirits of our African ancestors regardless of where we live or which villages or towns we come from.

She smiled and whispered to her friends in her West African dialect. I didn’t understand what she was saying, but all of the children smiled and waved to me as I left their village.

Are my people Igbo from Nigeria, or Fulani from Mali, or Wolof from Senegal, or Ashanti from Ghana? Sadly, I may never know. But somehow, as I stood on African soil, I felt at home.

CHAPTER 1

Instruction in youth is like engraving in stone. ∼ Moroccan proverb

I ZIP

UP MY

WET SUIT, adjust my mask, strap on my steel scuba tanks, breathe into my regulator, and slowly descend into a vast underwater world of translucent jellyfish, wide-winged manta rays, and giant sea turtles.

The gentle underwater currents nudge me along the colorful reefs—past the deep purple sea fans, the bursting orange coral heads, and the white tubular anemones that sway in the sea silt.

Bright yellow angelfish swim a few feet above me in synchronized rhythm.

Nearby, a shiny barracuda crosses my path with a snapped fishing line dangling from his mouth. He had no doubt stripped the bait from an unsuspecting fisherman and fled quickly into the deep.

In the distance, I watch the ocean’s most feared predators zig-zagging in and out of the shadows—the saw-toothed blacktip sharks that are more interested in observing the bubble-breathing scuba divers than confronting them.

I exhale and drop slowly to the sandy ocean floor.

I am a deep-sea scuba diver.

My love of the sea started when I was young. I grew up in a mostly black, middle-class neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan. In the evenings, I would sit in the living room watching Sea Hunt, an underwater adventure television program that aired when I was a boy in the late 1950s and early ’60s.

I enjoyed Sea Hunt because it was unlike anything I had ever seen. It featured ocean exploration and sunken ships and treasure—and I decided right then that I too would one day explore shipwrecks in distant oceans.

There was just one problem. Little boys from Detroit didn’t know much about scuba diving.

I was the only kid in my neighborhood who talked about diving, and I never missed an episode of this television show. My friends played basketball, football, and baseball. I enjoyed playing sports, too, but I yearned for travel and adventure.

For me, Sea Hunt was an escape of sorts, something to help me cope with the atmosphere surrounding the violent civil rights marches and demonstrations that were happening in Detroit at the time.

I didn’t know how to swim, but luckily my mother was not only supportive, she was also an excellent swimmer. She took me to the local pool and, in the protective shallow end, she taught me the “front crawl” and the breaststroke. Eventually she felt I was ready to master the deep end of the pool. I wasn’t so sure.

As I stood tentatively at the edge of the pool, looking into 10 terrifying feet of water, without warning, she pushed me in! I wish I could say that I swam around the pool with the grace of a delicate swan, but no—I sputtered and flailed to the side of the pool and clutched the cold tile as if it were a lifeline, gaping up at my mom and her sly smile.

But then, once my heart stopped racing, I looked back at the water and took a deep breath. I slipped under the surface and swam the entire length of the pool for the very first time. My mom told me how proud she was, and we drove home laughing about my first experience in the deep.

I’ve been swimming ever since.

This is a story about how my love of swimming, and later deep-sea diving, led me on a journey to three continents as I helped uncover the mystery surrounding a little-known 17th-century shipwreck. It’s about how I, along with others, pieced together a 300-year-old transatlantic puzzle that would teach me about myself—and where I came from. But more than that, it’s the untold story of millions of African people taken as captives to the New World, whose names and faces have been erased and eradicated by time, distance, and history.

CHAPTER 2

A patient person never misses a thing. ∼ Moroccan proverb

THE RUSTED

STEEL ANCHOR

CHAIN rumbled over the side of the Virgalona as the weathered boat engine sputtered to a stop.

Captain Demostenes “Moe” Molinar, a diesel mechanic turned boat captain from Panama and a legend among underwater treasure hunters, was at the helm of the Virgalona, his 51-foot salvage boat. He was monitoring the swift currents on the surface before making his decision to dive into the murky Gulf of Mexico.

It was July 1972 and Moe was searching for underwater treasure—and lots of it. He was looking for the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, a three-masted Spanish galleon that sank in 1622 after slamming into coral reefs during a hurricane. At the time, the ship was carrying chests full of gold, silver, and precious stones from Central and South America back to Spain. Moe and his team knew that there was so much treasure aboard that it took workers back then two months to record all the jewels and load it. Moe was hired by famed treasure hunter Mel Fisher to find glitter in the sand.

Over the course of more than a decade, Moe and his crew had researched the suspected location of the Nuestra Señora de Atocha by using a whole slew of technology and instruments, including side-scan sonars, metal detectors, and cesium magnetometers to search for piles of iron from Spanish galleons.

Moe and his mates were pretty confident that the fractured Spanish galleon rested on the ocean floor near an area known as the Marquesas Keys, about 25 miles west of Key West, Florida.

After Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the New World in 1492, the Spanish set out to conquer foreign colonies, and they would amass an array of riches during their voyages. During these roughly 400 years of plundering the New World, hurricanes occasionally tossed and sank Spain’s treasure ships, like the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, burying the bounty under layers of sand.

Based on extensive research by Mel Fisher and his family, Moe knew the Nuestra Señora de Atocha was within his reach, but locating the exact location of the ship on the seafloor would be like finding a needle in a haystack.

“It’s a big ocean out there and the bottom changes regularly,” Moe often told his crew.

Despite the odds, Moe was determined to find a cargo of riches.

Moe slipped on his fins, strapped on his scuba mask, popped his regulator into his mouth, and rolled backward off the Virgalona, plunging 30 feet into the Gulf of Mexico.

It was a familiar place.

Moe was known worldwide as one of the most accomplished treasure hunters in America—and certainly the most well-known black underwater treasure hunter in modern times.

Moe’s buddies say he used mystical abilities to locate underwater treasure when others had simply given up on their searches.

The Gulf of Mexico’s surface was choppy, so Moe knew he would need to descend quickly. His crew followed Moe into the water, one by one, and they all dropped under the foamy waves and down to the seafloor.

Swimming among the tall seagrass, Moe was annoyed by a fat-faced grouper that tugged on his regulator hose. The grouper probably confused Moe’s coiled scuba hose with the four-foot-long black worms that groupers like to eat. Moe gently pushed the grouper away and used his fins to kick through the silt.

He swam past sea fans, schools of colorful fish, and even sharks that circled nearby. Moe was accustomed to seeing sharks—big sharks, small sharks, aggressive sharks, and the kind of sharks that prefer to be left alone. And some sharks that just won’t go away.

On this particular day, Moe was harassed so much by a shark that he almost called off the search, worried for himself and his team.

After the shark finally left, Moe decided to make one last sweep of the shipwreck before calling it a day.

Moe saw something lying on the sand in the shadowy distance. After a few minutes of kicking hard against the current, he reached the object. Moe used his rugged hands to lightly part layers of sand and sediment from what appeared to be ancient relics.

As a veteran underwater treasure hunter, Moe had seen a lot of crazy things in his day, so he wasn’t easily surprised. But on that day, Moe was astounded by what he saw.

Moe stared at the small pile of iron caked in rust and limestone. He reached out to touch it. It was hard and menacing, and it sent a chill up his spine.

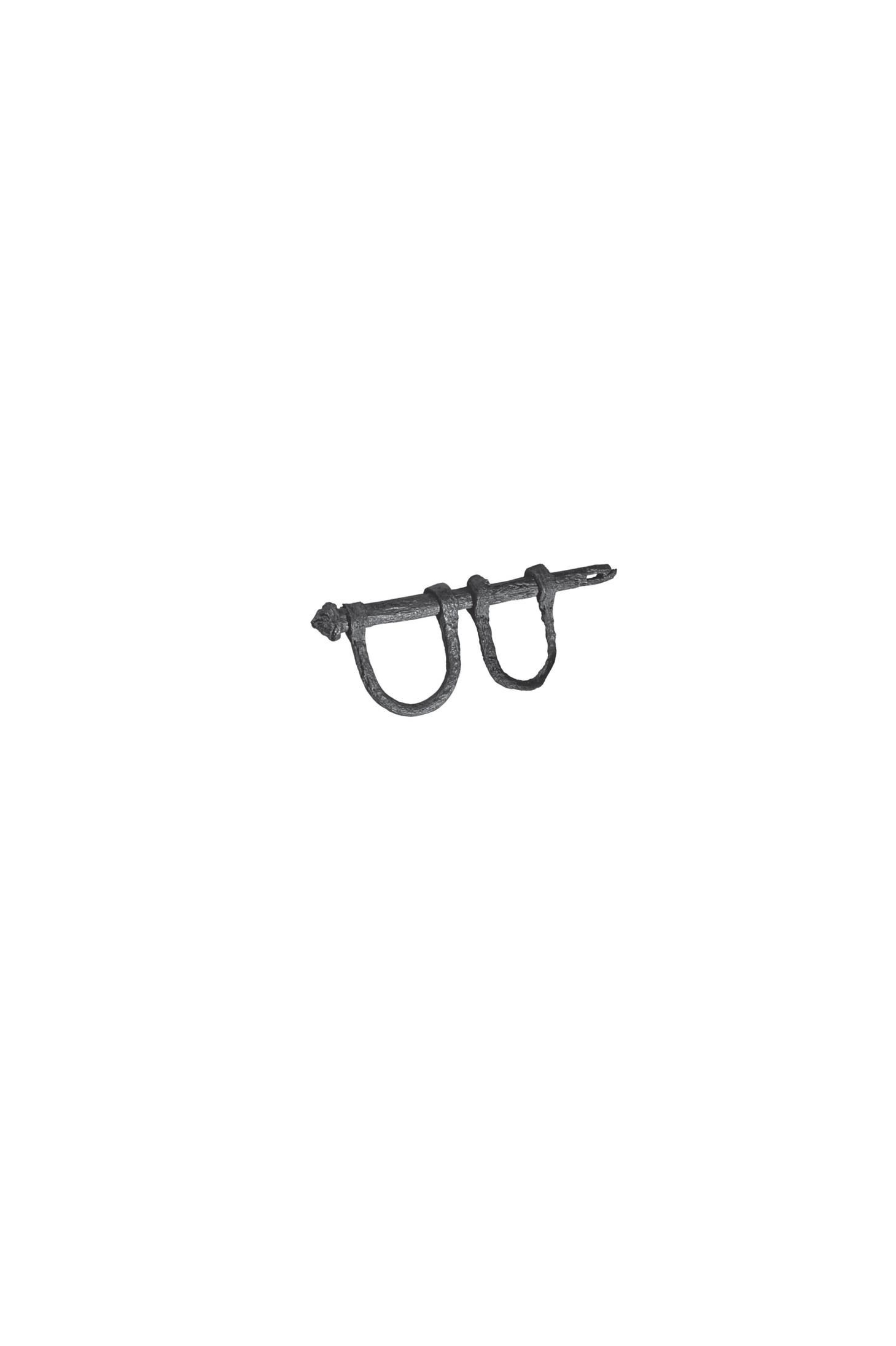

He gently picked up a large chunk of the iron and, with a sickening feeling, realized what he was holding in his seawater-wrinkled hands: a pair of hardened, ancient shackles—heavy manacles that he knew were designed specifically to handcuff the wrists of enslaved Africans, wrists that—he couldn’t help thinking—had probably looked much like his own.

Moe’s mind was racing with questions. Why were these shackles on this site? How did they get there? How long had they been there? He thought it unlikely that they would be from the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, which made him wonder, Where did these come from?

The discovery of the shackles made this shipwreck site different from all the other shipwrecks Moe had explored. He plunged his hands into the sand and began unearthing more shackles, several pairs at a time.

Each pair of shackles weighed six pounds and had two holes the size of quarters to hold a 13-inch-long bolt that locked into place to bind someone’s wrists tightly and efficiently. They were unyielding and they were sure to cause extreme discomfort and pain.

To give you an idea of how amazing it was that Moe even discovered this tiny mound of lost relics, you have to imagine how it must have been. A whole ocean stretches beneath you as, weightless, you peer hard through murky water and swirling sand, searching for a pinpoint of something slightly out of place—all against a backdrop of an ever shifting seafloor.

As he reached down into the sand again, Moe tugged at another pair of shackles from the pile, but these shackles were different from the others: They were tiny, thin, and almost flimsy, and they fit in the palm of Moe’s hand. He knew that these particular cuffs were designed specifically for the small wrists of children.

Suddenly Moe felt overwhelmed. Who would make handcuffs for children? And what kind of person would use these grisly tools? Where did these shackles come from and how many people had worn them?

Not all treasure is about glitter. Sometimes, along the route to discovery, we find something that is more valuable than precious stones. Sometimes we learn something about our human story and ourselves.

Moe’s discovery in and of itself was extraordinary—but it was even more so because of this: 300 years after those shackles were used to bind African people aboard a sweltering slave ship, the first man to touch those same shackles was Moe, a free black man.

While Moe and the crew began to survey the site in the Marquesas known as the New Ground Reef, they unearthed another artifact: an iron cannon weighing about 800 pounds. Moe was pretty sure he had stumbled upon the remains of a sunken slave ship. He surfaced with the shackles and went to work trying to make sense of what he’d found.

WHO WOULD MAKE HANDCUFFS FOR CHILDREN? AND WHAT KIND OF PERSON WOULD USE THESE GRISLY TOOLS?