The March Against Fear: The Last Great Walk of the Civil Rights Movement and the Emergence of Black Power

Meredith departed from Memphis, Tennessee, on foot, bound for Jackson, Mississippi, 220 miles away, on June 5, 1966. Friends and onlookers joined him for stretches of the first day’s walk. Credit 6

This time, Meredith wanted his activism to be different from the confrontation at Ole Miss. He wanted no federal troops, no bloodshed, no drama.

No big deal.

That was the plan.

He couldn’t have chosen a tougher place for his undertaking. Mississippi was arguably, in 1966, the most segregated, most oppressive state in the Union when it came to its treatment of African Americans. The Mississippi power structure ensured that whites controlled the governor’s office, the state legislature, and local communities. Whites served as judges, and jurors, and jailers. Whites ran its school boards, elections, and voter registration. Whites controlled the newspapers in the state and ran its most prosperous businesses. Whites dominated the farms that produced the cotton that was synonymous with Mississippi, a crop that for centuries had been picked almost exclusively by slaves and their descendants.

Meredith’s walk seemed guaranteed to provoke controversy. He would be striding into a state where people had threatened his life repeatedly during the Ole Miss fight just four years earlier. The sheer audacity of a black man walking into Mississippi, head held high, afraid of no one, could only spell trouble in an era when such organizations as the terror-based Ku Klux Klan and the less violent but equally racist local White Citizens’ Councils influenced life in Mississippi as much as—or more than—elected officials and the rule of law.

Despite the dangers, Meredith made the barest of plans for his trip, although he later claimed to have purchased a sizable life insurance policy to provide for his family in case someone killed him. He debated whether to arm himself. Months before his departure, Meredith had alerted local authorities of his intentions and requested law enforcement protection during his walk; perhaps he should trust he would be secure. Although Meredith had not seen himself as being devoted to the power of nonviolence, he wasn’t an advocate for violence either. In the end, he dismissed the idea of bringing a weapon and decided to arm himself with a Bible instead.

Meredith set off on the afternoon of Sunday, June 5, 1966, with $11.35 in his pockets. He carried no backpack, or bedroll, or food. “There are a million Negroes in Mississippi, and I think they’ll take care of me,” he told the cadre of reporters on hand to accompany him. A handful of local black supporters came along, too, as did several allies who had traveled from northern cities to take part in the effort. Memphis officials didn’t want to invite criticism for failing to protect Meredith if something went wrong, so a police escort joined the group, too.

The entourage departed from the historic Peabody Hotel in downtown Memphis, crossed through the city’s segregated neighborhoods, and passed the gates of Elvis Presley’s Graceland home, bound for the Mississippi state line. Most people along the route were friendly. Blacks waved. Whites generally stared or ignored him. A few people expressed their objections by jeering, making threatening comments, or waving the Confederate battle flag, a Civil War–period symbol that segregationists had resurrected during the civil rights era.

Meredith hiked with his own symbols, including a walking stick made from ebony and ivory that a Sudanese village chief had given him during his stay in Africa. “We shall arrive,” the chief had told his American friend at the time; Meredith hoped the memory would serve him well on his new journey. Meredith wore a short-sleeved cotton shirt, gray slacks, and hiking boots on that hot, sunny afternoon. He shaded his face with a yellow pith helmet, another symbol of his connection to Africa. After covering 12 miles in fewer than five hours, Meredith reached his objective for the day: Mississippi. The state line lay just ahead and could wait until tomorrow.

He and his companions resumed their walk the next morning, Monday, June 6, accompanied once again by members of a press corps that, at the time, was predominately composed of white men. Mississippi law enforcement officers took the place of those from Tennessee as they crossed the boundary. The high point for Meredith on the second day’s hike came when they reached Hernando, the first town south of the state line. Some 150 local blacks turned out to greet him, offer encouragement, and give him assistance—everything from a free hamburger to a dollar bill.

“I was ecstatic,” Meredith recalled, decades later. He hadn’t been sure if his walk would inspire others to be brave. Just gathering to meet him took real nerve during an era when any demonstration of support for racial equality in the Deep South could trigger retaliation from whites who controlled the region’s jobs and jails. When he’d set out on his walk, Meredith had believed, as he would later state, that the “day for Negro men being cowards is over,” and here was evidence that he was right.

Then 90 minutes later a gunman literally stopped James Meredith in his tracks.

“With this announcement black people across the country began crossing Meredith’s name from the list of those in the land of the living…

They were black and they knew.

Mr. Meredith had announced his death.”

Julius Lester, civil rights activist and author, recalling reactions to James Meredith’s announcement for his walk through Mississippi

“I don’t think it’s going to amount to much.”

Nicholas Katzenbach, attorney general of the United States, commenting on James Meredith’s plan to walk from Memphis to Jackson

“I think the entire incident is God’s gift to the civil rights movement. We can do with it what we will. If we accept it and build on it, who knows what might come of it?”

James Lawson’s thoughts for Martin Luther King, Jr., about the attack on James Meredith and his survival

After being ambushed on June 6, James Meredith fell beside a row of cars where witnesses to his attack had sought shelter. Credit 7

CHAPTER 2

REACTIONS

NOTHING ABOUT Aubrey Norvell’s life appeared particularly noteworthy until Monday, June 6, 1966, when he started firing a shotgun at an icon of the civil rights era. Norvell and his wife lived in a quiet suburban neighborhood in Memphis, Tennessee. They had no children. They’d married shortly after World War II, a conflict in which Norvell had served with distinction. He and his father had owned and run a local hardware store together until 1963; in recent months he had been unemployed. No one could recall him commenting for or against racial equality, nor did he have any known connections to white supremacy groups.

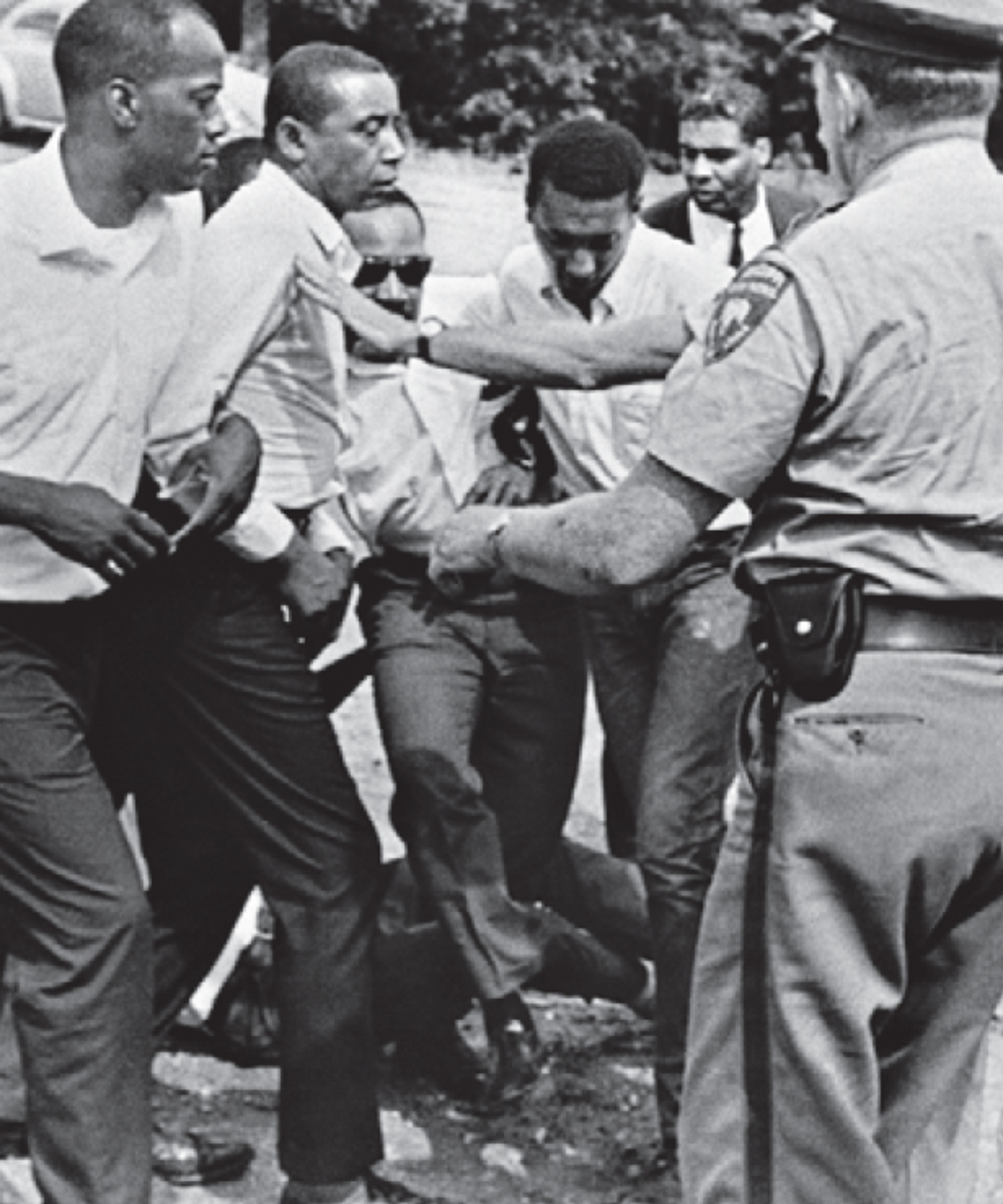

After firing three shots at James Meredith, Norvell had turned to reenter the roadside underbrush alongside Highway 51. Only then had law enforcement officers recovered from their shock at his sudden attack and arrested the gunman. Norvell offered no explanation for his actions, and his motivations remained a mystery. Perhaps due to Meredith’s prominence, the local judge set a steep bail for the attacker’s release, $25,000, a sum equivalent to more than $180,000 today. This was more than double the typical rate for such offenses, and it exceeded the value of the Norvell home. Unless someone helped to secure his bail, Norvell would remain behind bars until his trial, which was set for November.

Norvell’s silence, his unremarkable past, and his ability to attack Meredith despite the presence of law enforcement prompted widespread speculation. Many people shared a feeling of outrage: How could officials have just stood by and done nothing to stop the shooting? Others seemed annoyed: Mississippi is getting blamed even though the shooter is from Tennessee! Still others appeared bewildered: Why hadn’t Norvell—an experienced hunter with wartime commendation for marksmanship—used deadlier ammunition or aimed to kill?

DATE WALKED: June 7 MILES WALKED: 6 ROUTE: South of Hernando to north of Coldwater

In the absence of a more logical narrative, people began to invent explanations for what had occurred. Maybe Norvell had acted on behalf of a white supremacy effort and the police were in on the plan, some speculated. Or maybe someone sympathetic to the civil rights movement had hired Norvell to shoot Meredith and make Mississippi look bad, others suggested. Those who avoided conspiracy theories were left to conclude that Norvell must have been a confused man during confusing times, acting alone for no apparent reason. Initial press coverage of the shooting compounded the chaos, for some of the earliest and most prominent reports mistakenly claimed that Meredith had been shot dead.

Local law enforcement officers apprehended Aubrey Norvell at the scene of Meredith’s roadside shooting south of Hernando on June 6. Credit 8

Martin Luther King, Jr., had followed the breaking news from his home base in Atlanta, Georgia, two states east of Mississippi. Even after it became clear that Meredith had survived, King and his allies in the civil rights movement prepared to respond. Words of sympathy and concern would not be enough, leaders agreed during phone calls and staff meetings. The movement’s commitment to nonviolence required action, as well. Advocates for racial equality had to resume Meredith’s effort—with or without him—and continue until they reached his objective of Jackson. To do otherwise would allow violence to have the last word. Not acting would embolden those who opposed change.

Reaching that determination was easy; deciding how to execute the plan was not. The dimensions of the undertaking were staggering. Activists viewed the previous year’s walk from Selma to Montgomery as an unprecedented achievement, but the logistical challenges of completing Meredith’s hike dwarfed that undertaking by every measure. Distance. Time. Summer heat. Endless meals. Perpetual housing. Enormous costs. It would be a monumental challenge.

Movement leaders turned almost immediately to the Reverend James Lawson in Memphis for help. This veteran activist had joined the civil rights movement after meeting King in 1957. The two men shared a deep confidence in the power of nonviolence to bring about social change. Lawson had personally trained countless movement volunteers in the principles and practice of nonviolence, and many of his students had become essential activists in the struggle for equal rights. In 1962, Lawson had assumed leadership of Centenary United Methodist Church in Memphis, the region’s largest congregation of black Methodists. His prominence in the movement, his leadership role in the local area, his experience with nonviolent protests, his organizational skills—all these factors and more made him an ideal ally in making plans for a renewed walk.

Movement leaders (from left) Floyd McKissick, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Stokely Carmichael converged on Meredith’s hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, on June 7, one day after he’d been shot. Soon after the trio announced plans to revive his walk. Credit 9

National leaders mobilized overnight, and by Tuesday, June 7, Lawson was welcoming them to Memphis. By day’s end, leaders from all five of the nation’s leading civil rights organizations—the so-called Big Five—would be in town. The first to arrive were King, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Floyd McKissick, the newly appointed national director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They and some key associates piled into Lawson’s family car and headed to the hospital to see Meredith.

Stokely Carmichael, the newly elected chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) arrived soon after, accompanied by additional representatives of his group. Leaders of two other organizations visited Meredith later that day, as well, Whitney Young of the National Urban League and Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, spoken as “N-double-A-C-P”).

While Meredith, of course, knew all of the Big Five leaders by reputation, he found himself meeting some of them, such as King, for the first time. The arrival of such dignitaries at his bedside reinforced Meredith’s sense of his own importance. King, McKissick, Lawson, and Carmichael offered Meredith their concern and presented him with a proposal. It was clear that he faced a lengthy recovery. He had dozens of open wounds that needed to heal, and he was in no condition to resume marching. While he recuperated, they asked, would he let them organize an effort to continue his walk? If he made a speedy recovery, he could rejoin them later on.

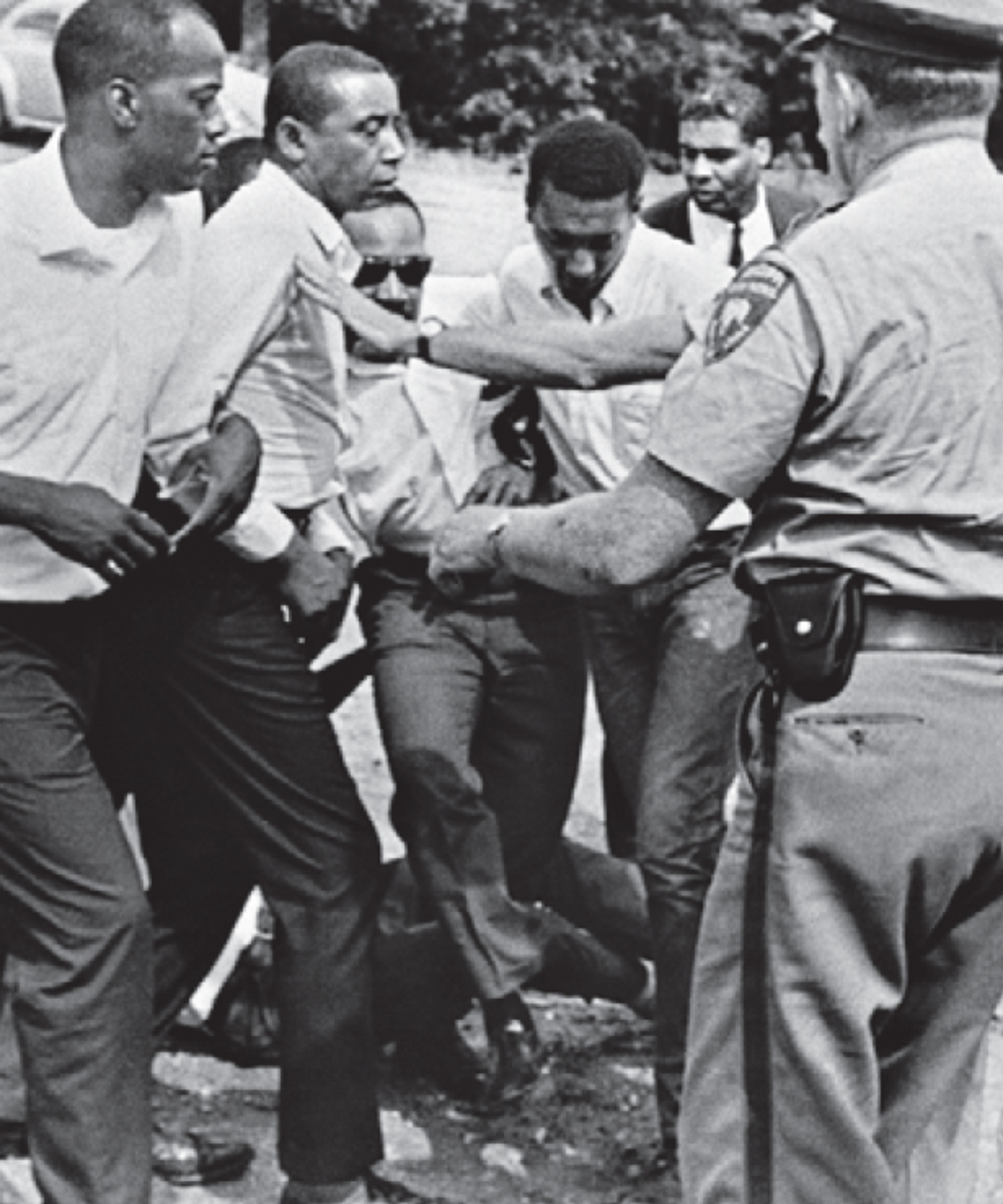

Mississippi state troopers ordered marchers off the pavement when they began walking in honor of James Meredith on June 7. When King objected, an officer shoved him toward the roadside. Credit 10

Overall the concept appealed to Meredith; he appreciated their endorsement of his effort and liked the idea of seeing it completed. But Meredith also realized that letting others carry on without him meant the walk would likely stray from his goals: Gone would be his plan for a small walk under his control from which he could exclude women and children. Meredith weighed the trade-offs and gave his visitors permission to proceed. The three leaders promised to seek his input while he recuperated and to keep Meredith updated as the walk progressed. Everyone agreed they needed to move fast.

Not even 24 hours had passed since Meredith’s shooting, and the news was still hot. By acting quickly, organizers would receive vital media coverage that would boost the flow of volunteers and donations for their effort. Details would have to fall into place as they went. The first priority was to return to Highway 51. By doing so, the leaders would demonstrate the movement’s determination to revive a campaign interrupted by violence. They made plans to start walking that very day from the spot where Meredith’s blood had stained the highway. Before nightfall, more than a dozen men—including King, McKissick, Carmichael, and Lawson—had covered some six miles of new ground. Then they returned to their temporary base in Memphis to regroup.

That evening hundreds of people joined the day’s marchers for a rally at Lawson’s church. They sang freedom songs and listened to a parade of speakers. Representatives from each of the Big Five civil rights organizations shared their outrage over the shooting, their intention to complete the walk to Jackson, and their impatience with the pace of change. Wilkins, of the NAACP, spoke at the rally about how the residents of Meredith’s home state seemed to be living in “another country” that followed a different set of laws and standards. He promised the crowd, “We are going to show the people of Mississippi that they are part of the 50 states,” and therefore they must follow its laws. Speakers outlined the motivation for the effort, including their determination to answer a violent act with nonviolent solidarity.

But there were other reasons to act, as well. Like Meredith, they wanted to encourage blacks to become registered voters. And they hoped that their walk toward Jackson, when combined with shock over Meredith’s shooting, would prompt members of Congress to pass the civil rights bill of 1966, the latest proposal in a series of such legislation. If approved, the bill would make it illegal to discriminate in housing and jury selection; extend federal protection to civil rights workers; and expand the integration of public schools. The march from Selma to Montgomery had influenced the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; perhaps another great march—the Meredith march—would inspire lawmakers to act again.

Even as they fired up the local base and sent appeals for support to allies around the country, movement leaders still needed to determine how to pull off their plans. That night, after the public meeting at Lawson’s church, representatives from the Big Five crammed into one of the guest rooms at the Lorraine Motel to establish the fundamentals. Slowly, over the course of a long and contentious discussion, civil rights leaders and their associates debated what to do.

Would voter registration be the focus of the march? Or passage of the civil rights bill? Both, if possible. They considered what roles whites should play in the protest. Some asked if whites should even be included at all: Wasn’t it time for blacks to stand up on their own? Organizers compromised. Whites would be welcome to participate, but the effort would depend on African-American leadership and support.

Leaders debated the role of nonviolence versus the need for security. Could the Mississippi police be trusted to keep the marchers safe? Or should armed guards help protect participants? They finally agreed that the power of nonviolence would guide the effort; therefore, marchers would be unarmed. But, adopting a strategy already employed for other SNCC and CORE projects in the Deep South, members of a southern organization called the Deacons for Defense and Justice would accompany them as bodyguards, ready to defend the marchers from attacks by Klan members and other white supremacists.

Three of the Big Five groups had already expressed their support for a renewed march, and each brought its own strengths to the effort. McKissick’s CORE could recruit plenty of volunteers but had little money. Carmichael’s SNCC had the best sense of the territory they would cross, having done fieldwork in rural Mississippi since 1962. The SCLC, led by King, had access to donors. Furthermore, King’s presence automatically guaranteed increased media coverage, funding, and participation. By joining forces, they might truly make a difference to the local people through voter registration drives while continuing the momentum of the national fight for civil rights. Maybe, as Carmichael hoped, their successes could “really make this the last march” for the movement.

The other Big Five leaders—Whitney Young of the National Urban League and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP—thought the goals for the revived walk were too fragmented. They wanted to focus only on passing the civil rights bill, not voter registration, too. And they regarded the militant tone of SNCC leaders as both counterproductive and offensive. Hearing the youthful Carmichael refer to Lyndon B. Johnson, the president of the United States, with street slang as “that cat Johnson,” helped to send them packing. Their departure deprived the march of extra financial support and the appearance of Big Five unity, but it strengthened the ability of the participating trio of organizations to focus on their shared goals for the undertaking.

The remaining leaders crafted a document to summarize their motivations for the march, which they called their manifesto. This statement called on President Johnson to increase the nation’s investment in the country’s African-American citizens in four ways: enforcement of legal rights, increased economic opportunity, improved voting access, and greater representation by blacks on juries and police forces. Some of these concerns would be addressed by the proposed civil rights bill, but not all of them. Leaders of the revived march asked for broader action.

It was one o’clock in the morning by the conclusion of the meeting. Movement leaders settled down for a few hours of rest, knowing they’d be back on the road after daylight, traveling to the spot where they’d left off walking the day before. Until they could make more permanent arrangements, they planned to sleep in Memphis by night and walk in Mississippi by day, with each new hike extending their commute between the two locations.

Meredith remained in Memphis, too. Doctors had recommended he stay under observation at the hospital until he flew home to New York on Thursday. Those plans changed unexpectedly, though, on Wednesday, June 8. That morning, King and McKissick had stopped by Meredith’s room to secure his support of their newly created manifesto. A hospital administrator interrupted their meeting to inform Meredith that he was to be discharged a day early. Regardless of his condition, hospital personnel had grown tired of the security concerns, news media attention, and high-profile visitors that accompanied his stay.

Meredith, King, and McKissick protested this unexpected eviction, but the hospital staff held firm. He had to leave that day. When Meredith tried to speak to reporters as he departed, he fainted from the sudden exertion and stress. Medical personnel revived him then ferried him to the curb in a wheelchair. Meredith flew home later that day. June Meredith had remained in New York with their six-year-old son, John, during her husband’s walk and hospitalization. That evening she met his flight, joined by a throng of reporters. “I shall return to my divine responsibility,” a weakened Meredith told the journalists, “and we shall reach our destination.”

Despite his injuries—or, really, because of them—Meredith felt angry. He had entrusted his safety to local law enforcement officers, and they had failed him. Meredith, the military veteran who liked to plan with precision, wondered if he’d made a mistake when he’d brought a Bible to Mississippi instead of a gun. The day after his attack he had conveyed his frustration with dramatic language in a written statement for the press: “I could have knocked this intended killer off with one shot had I been prepared.” Journalists knew the idea of anyone taking the law into his own hands, even in self-defense, could be seen as inflammatory and controversial. Thus, when reporters had the chance to question Meredith in New York, they pressed him on his comment and asked if he would arm himself should he be able to rejoin the campaign.

Meredith noted that he had turned to state officials for protection originally, and it hadn’t worked; deputies had been present, but they had just stood by while Norvell took shots at him. Could he be confident they’d behave any differently the next time? Meredith told the reporters that if he could not count on receiving protection from local law enforcement personnel, then he had the right to consider arming himself in self-defense when he rejoined the march. When someone asked how he squared such a thought with the doctrine of nonviolence, Meredith replied, “Who the hell ever said I was nonviolent? I spent eight years in the military and the rest of my life in Mississippi.”

Nonviolent protest or not, James Meredith didn’t plan to get shot again.

“The shooting of James Meredith is further savage proof that brutality is still the white American way of life in Mississippi.”

Floyd McKissick, national director for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), June 6, 1966