Death and the Dancing Footman

‘Come along, Nick,’ said Jonathan, and when it appeared that Nicholas had not heard him, he murmured in an undertone: ‘You and William go on, Aubrey. We’ll follow.’

So Mandrake and William did not hear what Nicholas and Dr Hart had to say to each other.

IV

Mandrake had suspected that if Jonathan failed it would be from too passionate attention to detail. He feared that Jonathan’s party would die of over-planning. Having an intense dislike of parlour-games, he thought gloomily of sharpened pencils and pads of paper neatly set out by the new footman. In this he misjudged his host. Jonathan introduced his game with a tolerable air of spontaneity. He related an anecdote of another party at which the game of Charter had been played. Jonathan had found himself with a collection of six letters and one blank. When the next letter was called it chimed perfectly with his six, but the resulting word was one of such gross impropriety that even Jonathan hesitated to use it. A duchess of formidable rigidity had been present. ‘I encountered her eye. The glare of a basilisk, I assure you. I could not venture. But the amusing point of the story,’ said Jonathan, ‘is that I am persuaded her own letters had fallen in the same order. We played for threepenny points, and she loathes losing her money. I hinted at my own dilemma, and saw an answering glint. She was in an agony.’

‘But what is the game?’ asked Mandrake, knowing that somebody was meant to ask this question.

‘My dear Aubrey, have you never played Charter? It is entirely vieux jeu nowadays, but I still confess to a passion for it.’

‘It’s simply a crossword game,’ said Hersey. ‘You are each given the empty crossword form and the letters are called one by one from a pack of cards. The players put each letter, as it is read out, into a square of the diagram. This goes on until the form is full. The longest list of complete words wins.’

‘You score by the length of the words,’ said Chloris. ‘Seven-letter words get fifteen points, three-letter words two points, and so on. You may not make any alterations, of course.’

‘It sounds entertaining,’ said Mandrake with a sinking heart.

‘Shall we?’ asked Jonathan, peering at his guests. ‘What does everybody think? Shall we?’

His guests, prompted by champagne and brandy to desire, vaguely, success rather than disaster, cried out that they were all for the game, and the party moved to the smoking room. Here, Jonathan, with a convincing display of uncertainty, hunted in a drawer where Mandrake had seen him secrete the printed block of diagrams and the requisite number of pencils. Soon they were sitting in a semicircle round the fire with their pencils poised and with expressions of indignant bewilderment on their faces. Jonathan turned up the first card:

‘X,’ he said, ‘X for Xerxes.’

‘Oh, can’t we have another,’ cried Madame Lisse, ‘there aren’t any – Oh, no, wait a moment. I see.’

‘K for King.’

Mandrake, finding himself rather apt at the game, began to enjoy it. With the last letter he completed his long word, ‘extract,’ and with an air of false modesty handed his Charter to Chloris Wynne, his next-door neighbour, to mark. He himself took William’s Charter, and was embarrassed to find it in a state of the strangest confusion. William had either failed to understand the game, or else had got left so far behind that he could not catch up with the letters. Many of the spaces were blank, and in the left-hand corner William had made a singular little drawing of a strutting rooster, with a face that certainly bore a strong resemblance to his brother Nicholas.

‘Anyway,’ said William, looking complacently at Mandrake, ‘the drawing is quite nice. Don’t you think so?’

Mandrake was saved from making a reply by Nicholas, who at that moment uttered a sharp ejaculation.

‘What’s up, Nick?’ asked Jonathan.

Nicholas had turned quite pale. In his left hand he held two of the Charter forms. He separated them and crushed one into a wad in his right hand.

‘Have I made a mistake?’ asked Dr Hart softly.

‘You’ve given me two forms,’ said Nicholas.

‘Stupid of me. I must have torn them off the block at the same time.’

‘They have both been used.’

‘No doubt I forgot to remove an old form, and tore them off together.’

Nicholas looked at him. ‘No doubt,’ he said.

‘You can see which is the correct form by my long word. It is “threats.”’

‘I have not missed it,’ said Nicholas, and turned to speak to Madame Lisse.

V

Mandrake went to his room at midnight. Before switching on his light he pulled aside the curtains and partly opened the window. He saw that at last the snow had come. Fleets of small ghosts drove steeply forward from darkness into the region beyond the windowpanes, where they became visible in the firelight. Some of them, meeting the panes, slid down their surface and lost their strangeness in the cessation of their flight. Though the room was perfectly silent, this swift enlargement of oncoming snowflakes beyond the windows suggested to Mandrake a vast nocturnal whispering. He suddenly remembered the blackout and closed the window. He let fall the curtain, switched on the light, and turned to stir his fire. He was accustomed to later hours and felt disinclined for sleep. His thoughts were busy with memories of the evening. He was filled with a nagging curiosity about the second Charter form, which had caused Nicholas Compline to turn pale and to look so strangely at Dr Hart. He could see Nicholas’s hand thrusting the crumpled form down between the seat and the arm of his chair. ‘Perhaps it is still there,’ Mandrake thought. ‘Without a doubt it is still there. Why should it have upset him so much? I shall never go to sleep. It is useless to undress and get into bed.’ And the prospect of the books Jonathan had chosen so carefully for his bedside filled him with dismay. At last he changed into pyjamas and dressing-gown, visited the adjoining bathroom, and noticed that there was no light under the door from the bathroom into William’s bedroom at the farther side. ‘So William is not astir.’ He returned to his room, opened the door into the passage, and was met by the indifferent quiet of a sleeping house. Mandrake left his own door open and stole along the passage as far as the stairhead. In the wall above the stairs was a niche from which a great brass Buddha, indestructible memorial to Jonathan’s Anglo-Indian grandfather, leered peacefully at Mandrake. He paused here, thinking. ‘A few steps down to the landing, then the lower flight to the hall. The smoking room door is almost opposite the foot of the stairs.’ Nicholas had sat in the fourth chair from the end. Why should he not go down and satisfy himself about the crumpled form? If by any chance someone was in the smoking room he could get himself a book from the library next door and return. There was no shame in looking at a discarded paper from a round game.

He limped softly to the head of the stairs. Here, in the diffused light, he found a switch and turned it on. A wall-lamp halfway down the first flight came to life. Mandrake descended the stairs. The walls sighed to his footfall, and near the bottom one of the steps creaked so loudly that he started and then stood rigid, his heart beating hard against his ribs. ‘This is how burglars and illicit lovers feel,’ thought Mandrake, ‘but why on earth should I?’ Yet he stole cat-footed across the hall, pushed open the smoking room door with his fingertips and waited long in the dark before he groped for the light-switch and snapped it down.

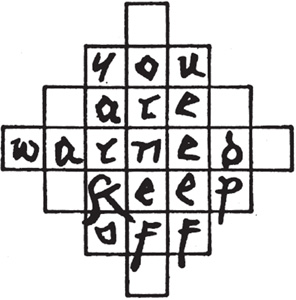

There stood the nine armchairs in a semicircle before a dying fire. They had an air of being in dumb conclave, and their irregular positions were strangely eloquent of their late occupants. There was Nicholas Compline’s chair, drawn close to Madame Lisse’s and turned away contemptuously from Dr Hart’s saddle back. Mandrake actually fetched a book from a sporting collection in a revolving case before he moved to Nicholas’s chair, before his fingers explored the crack between the arm and the seat. The paper was crushed into a tight wad. He smoothed it out on the arm of the chair and read the five words that had been firmly pencilled in the diagram.

The fire settled down with a small clink of dead embers, and Mandrake, smiling incredulously, stared at the scrap of paper in his hand. It crossed his mind that perhaps he was the victim of an elaborate joke, that Jonathan had primed his guests, had invented their antipathies, and now waited maliciously for Mandrake himself to come to him, agog with this latest find. ‘But that won’t wash,’ he thought. ‘Jonathan could not have guessed I would return to find the paper. Nicholas did change colour when he saw it. I must presume that Hart did write this message and hand it to Nicholas with the other. He must have been crazy with fury to allow himself such a ridiculous gesture. Can he suppose that Nicholas will be frightened off the lady? No, it’s too absurd.’

But, as if in answer to his speculations, Mandrake heard a voice speaking behind him: ‘I tell you, Jonathan, he means trouble. I’d better get out.’

For a moment Mandrake stood like a stone, imagining that Jonathan and Nicholas had entered the smoking-room behind his back. Then he turned, and found the room still empty, and realized that Nicholas had spoken from beyond the door into the library, and for the first time noticed that this door was not quite shut. He was still speaking, his voice raised hysterically.

‘It will be better if I clear out now. A pretty sort of party it’ll be! The fellow’s insane with jealously. For her sake – don’t you see – for her sake –’

The voice paused, and Mandrake heard a low murmur from Jonathan, interrupted violently by Nicholas.

‘I don’t give a damn what they think.’ Evidently Jonathan persisted, because in a moment Nicholas said: ‘Yes, of course I see that, but I can say …’ His voice dropped, and the next few sentences were half-lost. ‘… it’s not that … I don’t see why … urgent call from headquarters … Good Lord, of course not! … Miserable fat little squirt. I’ve cut him out and he can’t take it.’ Another pause, and then: ‘I don’t mind if you don’t. It was more on your account than … But I’ve told you about the letter, Jonathan … not the first … Well, if you think … Very well, I’ll stay.’ And for the first time Mandrake caught Jonathan’s words: ‘I’m sure it’s better, Nick. Can’t turn tail, you know. Good night.’ ‘Good night,’ said Nicholas, none too graciously, and Mandrake heard the door from the library to the hall open and close. Then from the next room came Jonathan’s reedy tenor:

‘Il était une bergère

Qui ron-ton-ton, petit pat-a-plan.’

Mandrake stuck out his chin, crossed the smoking room, and entered the library by the communicating door.

‘Jonathan,’ he said, ‘I’ve been eavesdropping.’

VI

Jonathan was sitting in a chair before the fire. His short legs were drawn up, knees to chin, and he hugged his shins like some plump and exultant kobold. He turned his spectacles towards Mandrake, and, by that familiar trick of light, the thick lenses obscured his eyes and glinted like two moons.

‘I’ve been eavesdropping,’ Mandrake repeated.

‘My dear Aubrey, come in, come in. Eavesdropping? Nonsense. You heard our friend Nicholas? Good! I was coming to your room to relate the whole story. A diverting complication.’

‘I only heard a little of what he said. I’d come down to the smoking room.’ He saw Jonathan’s spectacles turned on the book he still held in his hand. ‘Not really to fetch a book,’ said Mandrake.

‘No? One would seek a book in the library, one supposes. But I am glad my choice for your room was not ill-judged.’

‘I wanted to see this.’

Like a small boy in disgrace, Mandrake extended his right hand and opened it, disclosing the crumpled form.

‘Ah,’ said Jonathan.

‘You have seen it?’

‘Nick told me about it. I wondered if anyone else would share my own curiosity. May I have it? Ah – Thank you. Sit down, Aubrey.’ Mandrake sat down, tortured by the suspicion that Jonathan was laughing at him.

‘You see,’ said Mandrake, ‘that I am badly inoculated with your virus. I simply could not go to bed without knowing what was on that form.’

‘Nor I, I assure you. I was about to look for it myself. As perhaps you heard, Nick is in a great tig. It seems that before coming here he had had letters from Hart warning him off the lady. According to Nick, Hart is quite mad for love of her and consumed by an agonizing jealousy.’

‘Poor swine,’ said Mandrake.

‘What? Oh, yes. Very strange and uncomfortable. I must confess that I believe Nick is right. Did you notice the little scene after dinner?’

‘You may remember that you gave me to understand very definitely that my cue was to withdraw rapidly.’

‘So I did. Well, there wasn’t much in it. He merely glared at Nick across the table, and said something in German which neither of us understood.’

‘You’ll be telling me next he’s a fifth columnist,’ said Mandrake.

‘Not at all. He gives himself away much too readily. But I fancy he has frightened Nick. I have observed, my dear Aubrey, that of the two Complines, William catches your attention more than Nicholas. I have known them all their lives, and I suggest that you turn your eyes on Nicholas. Nicholas is rapidly becoming the – not perhaps the jeune premier – but the central character of our drama. In Nicholas we see the vain man, frightened. The male flirt who finds an agreeable stimulant in another man’s jealousy, and suddenly realizes that he has roused the very devil in his rival. Would you believe it, Nicholas wanted to leave tonight? He advanced all sorts of social and gallant reasons, consideration for me, for the lady, for the success of the party; but the truth is Nick had a jitterbug and wanted to make off.’

‘How did you prevent him?’

‘I?’ Jonathan pursed his lips. ‘I have usually been able to manage Nicholas. I let him see I understood his real motive. He was afraid I would make a pleasing little anecdote of his flight. His vanity won. He will remain.’

‘But what does he think Hart will do?’

‘He used the word “murderous.”’

There was a long silence. At last Mandrake said: ‘Jonathan, I think you should have let Nicholas Compline go.’

‘But why?’

‘Because I agree with him. I have watched Hart tonight. He did look murderous.’

‘Gorgeous!’ Jonathan exclaimed, and hugged his hands between his knees.

‘Honestly, I think he means trouble. He’s at the end of his tether.’

‘You don’t think he’ll go for Nick with a dinner-knife?’

‘I don’t think he’s responsible for his behaviour.’

‘He was a little tipsy, you know.’

‘So was Compline. While the champagne and brandy worked he rather enjoyed baiting Hart. Now, evidently, he’s not so sure. Nor am I.’

‘You disappoint me, Aubrey. Our æsthetic experiment is working beautifully and your only response –’

‘Oh, I’m absorbingly interested. If you don’t mind – after all, it’s your house.’

‘Exactly. And my responsibility. I assembled the cast, and, my dear fellow, I offered you a seat in the stalls. The play is going too well for me to stop it at the close of the first act. It falls very prettily on Nick’s exit, and I fancy the last thing we hear before the curtain blots out the scene is a sharp click.’

‘What?’

‘Nicholas Compline turning the key in his bedroom door.’

‘I hope to God you’re right,’ said Mandrake.

CHAPTER 5

Attempt

I

The next morning Mandrake woke at the rattle of curtain rings to find his room penetrated by an unearthly light, and knew that Highfold was under snow. A heavy fall, the maid said. There were patches of clear sky, but the local prophets said they’d have another storm before evening. She rekindled his fire and left him to stare at his tea-tray and to remember that, not so many years ago, Mr Stanley Footling, in the attic-room of his mother’s boardinghouse in Dulwich, had enjoyed none of these amenities. Stanley Footling always showed a tendency to return at the hour of waking, and this morning Mandrake asked himself for the hundredth time why he could not admit his metamorphosis with an honest gaiety; why he should suffer the miseries of unconfessed snobbery. He could find no answer, and, tired of his thoughts, decided to rise early.

When he went downstairs he found William Compline alone at the breakfast-table.

‘Hallo,’ said William. ‘Good morning. Jolly day for Nick’s bath, isn’t it?’

‘What!’

‘Nick’s bath in the pool. Have you forgotten the bet?’

‘I should think he had.’

‘I shall remind him.’

‘Well,’ said Mandrake, ‘personally I should pay a good deal more than ten pounds to get out of it.’

‘Yes, but you’re not my brother Nicholas. He’ll do it.’

‘But,’ said Mandrake uncomfortably, ‘hasn’t he got something wrong with his heart? I mean –’

‘It won’t hurt him. The pool’s not frozen. I’ve been to look. He can’t swim, you know, so he’ll just have to pop in at the shallow end and duck.’ William gave a little crow of laughter.

‘I’d call it off, if I were you.’

‘Yes,’ said William, ‘but you’re not me. I’ll remind him of it, all right.’ And on this slightly ominous note they continued with their breakfast in silence. Hersey Amblington and Chloris Wynne came in together, followed by Jonathan, who appeared to be in the best of spirits.

‘We shall have a little sunshine, I believe,’ said Jonathan. ‘It may not last long, so doubtless the hardier members of the party will choose to make the most of it.’

‘I don’t propose to build a snowman, Jonathan, if that’s what you’re driving at,’ said Hersey.

‘Don’t you, Hersey?’ said William. ‘I rather thought I might. After Nick’s bath, you know. Have you heard about Nick’s bath?’

‘Your mother told me. You’re not going to hold him to it, William?’

‘He needn’t if he doesn’t want to.’

‘Bill,’ said Chloris, ‘don’t remind him of it. Your mother –’

‘She won’t get up for ages,’ said William, ‘and I don’t suppose there’ll be any need to remind Nick. After all, it was a bet.’

‘I think you’re behaving rather badly,’ said Chloris uncertainly. William stared at her.

‘Are you afraid he’ll get a little cold in his nose?’ he asked, and added: ‘I was up to my waist in snow and slush in France not so long ago.’

‘I know, darling, but –’

‘Here is Nick,’ said William placidly. His brother came in and paused at the door.

‘Good morning,’ said William. ‘We were just talking about the bet. They all seem to think I ought to let you off.’

‘Not at all,’ said Nicholas. ‘You’ve lost your tenner.’

‘There!’ said William. ‘I said you’d do it. You mustn’t get that lovely uniform wet, Nick. Jonathan will lend you a bathing suit, I expect. Or you could borrow my uniform. It’s been up to –’ Mandrake, Chloris, Hersey, and Jonathan all began to speak at once, and William, smiling gently, fetched himself another cup of coffee. Nicholas turned away to the sideboard. Mandrake had half-expected Jonathan to interfere, but he merely remarked on the hardihood of the modern young man and drew a somewhat tiresome analogy from the exploits of ancient Greeks. Nicholas suddenly developed a sort of gaiety that set Mandrake’s teeth on edge, so falsely did it ring.

‘Shall you come and watch me, Chloris?’ asked Nicholas, seating himself beside her.

‘I don’t approve of your doing it.’

‘Oh, Chloris! Are you angry with me? I can’t bear it. Tell me you’re not angry with me. I’m doing it all for your sake. I must have an audience. Won’t you be my audience?’

‘Don’t be a fool,’ said Chloris. ‘But, damn it,’ thought Mandrake, ‘she’s preening herself, all the same.’ Dr Hart arrived, and was very formal with his greetings. He looked ghastly and breakfasted on black coffee and toast. Nicholas threw him a glance curiously compounded of malice and nervousness, and began to talk still more loudly to Chloris Wynne of his bet with William. Hersey, who had evidently got sick of Nicholas, suddenly said she thought it was time to cut the cackle and get to the ’osses.

‘But everybody isn’t here,’ said William. ‘Madame Lisse isn’t here.’

‘Divine creature!’ exclaimed Nicholas affectedly, and showed the whites of his eyes at Dr Hart. ‘She’s in bed.’

‘How do you know?’ asked William, against the combined mental opposition of the rest of the party.

‘I’ve investigated. I looked in to say good morning on my way down.’

Dr Hart put down his cup with a clatter and walked quickly out of the room

‘You are a damned fool, Nick,’ said Hersey softly.

‘It’s starting to snow again,’ said William. ‘You’d better hurry up with your bath.’

II

Mandrake thought that no wager had ever fallen as inauspiciously as this one. Even Jonathan seemed uneasy, and when they drifted into the library made a half-hearted attempt to dissuade Nicholas. Lady Hersey said flatly that she thought the whole affair extremely boring and silly. Chloris Wynne at first attempted an air of jolly house-party waggishness, but a little later Mandrake overheard her urging William to call off the bet. Mrs Compline somehow got wind of the project and sent down a message forbidding it, but this was followed by a message from Madame Lisse saying that she would watch from her bedroom window. Mandrake tried to get up a party to play badminton in the barn, but nobody really listened to him. An atmosphere of bathos hung over them like a pall, and through it William remained complacent and Nicholas embarrassingly flamboyant.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов