The Mysterious Affair at Styles

‘And he’s a great friend of Mary’s,’ put in Cynthia, the irrepressible.

John Cavendish frowned and changed the subject.

‘Come for a stroll, Hastings. This has been a most rotten business. She always had a rough tongue, but there is no stauncher friend in England than Evelyn Howard.’

He took the path through the plantation, and we walked down to the village through the woods which bordered one side of the estate.

As we passed through one of the gates on our way home again, a pretty young woman of gipsy type coming in the opposite direction bowed and smiled.

‘That’s a pretty girl,’ I remarked appreciatively.

John’s face hardened.

‘That is Mrs Raikes.’

‘The one that Miss Howard –’

‘Exactly,’ said John, with rather unnecessary abruptness.

I thought of the white-haired old lady in the big house, and that vivid wicked little face that had just smiled into ours, and a vague chill of foreboding crept over me. I brushed it aside.

‘Styles is really a glorious old place,’ I said to John.

He nodded rather gloomily.

‘Yes, it’s a fine property. It’ll be mine some day—should be mine now by rights, if my father had only made a decent will. And then I shouldn’t be so damned hard up as I am now.’

‘Hard up, are you?’

‘My dear Hastings, I don’t mind telling you that I’m at my wits’ end for money.’

‘Couldn’t your brother help you?’

‘Lawrence? He’s gone through every penny he ever had, publishing rotten verses in fancy bindings. No, we’re an impecunious lot. My mother’s always been awfully good to us, I must say. That is, up to now. Since her marriage, of course –’ He broke off, frowning.

For the first time I felt that, with Evelyn Howard, something indefinable had gone from the atmosphere. Her presence had spelt security. Now that security was removed—and the air seemed rife with suspicion. The sinister face of Dr Bauerstein recurred to me unpleasantly. A vague suspicion of everyone and everything filled my mind. Just for a moment I had a premonition of approaching evil.

Chapter 2

The 16th and 17th of July

I had arrived at Styles on the 5th of July. I come now to the events of the 16th and 17th of that month. For the convenience of the reader I will recapitulate the incidents of those days in as exact a manner as possible. They were elicited subsequently at the trial by a process of long and tedious cross-examinations.

I received a letter from Evelyn Howard a couple of days after her departure, telling me she was working as a nurse at the big hospital in Middlingham, a manufacturing town some fifteen miles away, and begging me to let her know if Mrs Inglethorp should show any wish to be reconciled.

The only fly in the ointment of my peaceful days was Mrs Cavendish’s extraordinary and, for my part, unaccountable preference for the society of Dr Bauerstein. What she saw in the man I cannot imagine, but she was always asking him up to the house, and often went off for long expeditions with him. I confess that I was quite unable to see his attraction.

The 16th of July fell on a Monday. It was a day of turmoil. The famous bazaar had taken place on Saturday, and an entertainment, in connection with the same charity, at which Mrs Inglethorp was to recite a War poem, was to be held that night. We were all busy during the morning arranging and decorating the Hall in the village where it was to take place. We had a late luncheon and spent the afternoon resting in the garden. I noticed that John’s manner was somewhat unusual. He seemed very excited and restless.

After tea, Mrs Inglethorp went to lie down to rest before her efforts in the evening and I challenged Mary Cavendish to a single at tennis.

About a quarter to seven, Mrs Inglethorp called to us that we should be late as supper was early that night. We had rather a scramble to get ready in time; and before the meal was over the motor was waiting at the door.

The entertainment was a great success, Mrs Inglethorp’s recitation receiving tremendous applause. There were also some tableaux in which Cynthia took part. She did not return with us, having been asked to a supper party, and to remain the night with some friends who had been acting with her in the tableaux.

The following morning, Mrs Inglethorp stayed in bed to breakfast, as she was rather over-tired; but she appeared in her briskest mood about 12.30, and swept Lawrence and myself off to a luncheon party.

‘Such a charming invitation from Mrs Rolleston. Lady Tadminster’s sister, you know. The Rollestons came over with the Conqueror—one of our oldest families.’

Mary had excused herself on the plea of an engagement with Dr Bauerstein.

We had a pleasant luncheon, and as we drove away Lawrence suggested that we should return by Tadminster, which was barely a mile out of our way, and pay a visit to Cynthia in her dispensary. Mrs Inglethorp replied that this was an excellent idea, but as she had several letters to write she would drop us there, and we could come back with Cynthia in the pony-trap.

We were detained under suspicion by the hospital porter, until Cynthia appeared to vouch for us, looking very cool and sweet in her long white overall. She took us up to her sanctum, and introduced us to her fellow dispenser, a rather awe-inspiring individual, whom Cynthia cheerily addressed as ‘Nibs’.

‘What a lot of bottles!’ I exclaimed, as my eye travelled round the small room. ‘Do you really know what’s in them all?’

‘Say something original,’ groaned Cynthia. ‘Every single person who comes up here says that. We are really thinking of bestowing a prize on the first individual who does not say: “What a lot of bottles!” And I know the next thing you’re going to say is: “How many people have you poisoned?”’

I pleaded guilty with a laugh.

‘If you people only knew how fatally easy it is to poison someone by mistake, you wouldn’t joke about it. Come on, let’s have tea. We’ve got all sorts of secret stores in that cupboard. No, Lawrence—that’s the poison cupboard. The big cupboard—that’s right.’

We had a very cheery tea, and assisted Cynthia to wash up afterwards. We had just put away the last teaspoon when a knock came at the door. The countenances of Cynthia and Nibs were suddenly petrified into a stern and forbidding expression.

‘Come in,’ said Cynthia, in a sharp professional tone.

A young and rather scared-looking nurse appeared with a bottle which she proffered to Nibs, who waved her towards Cynthia with the somewhat enigmatical remark:

‘I’m not really here today.’

Cynthia took the bottle and examined it with the severity of a judge.

‘This should have been sent up this morning.’

‘Sister is very sorry. She forgot.’

‘Sister should read the rules outside the door.’

I gathered from the little nurse’s expression that there was not the least likelihood of her having the hardihood to retail this message to the dreaded ‘Sister’.

‘So now it can’t be done until tomorrow,’ finished Cynthia.

‘Don’t you think you could possibly let us have it tonight?’

‘Well,’ said Cynthia graciously, ‘we are very busy, but if we have time it shall be done.’

The little nurse withdrew, and Cynthia promptly took a jar from the shelf, refilled the bottle and placed it on the table outside the door.

I laughed.

‘Discipline must be maintained?’

‘Exactly. Come out on our little balcony. You can see all the outside wards there.’

I followed Cynthia and her friend and they pointed out the different wards to me. Lawrence remained behind, but after a few moments Cynthia called to him over her shoulder to come and join us. Then she looked at her watch.

‘Nothing more to do, Nibs?’

‘No.’

‘All right. Then we can lock up and go.’

I had seen Lawrence in quite a different light that afternoon. Compared to John, he was an astoundingly difficult person to get to know. He was the opposite of his brother in almost every respect, being unusually shy and reserved. Yet he had a certain charm of manner, and I fancied that, if one really knew him well, one could have a deep affection for him. I had always fancied that his manner to Cynthia was rather constrained, and that she on her side was inclined to be shy of him. But they were both gay enough this afternoon, and chatted together like a couple of children.

As we drove through the village, I remembered that I wanted some stamps, so accordingly we pulled up at the post office.

As I came out again, I cannoned into a little man who was just entering. I drew aside and apologized, when suddenly, with a loud exclamation, he clasped me in his arms and kissed me warmly.

‘Mon ami Hastings!’ he cried. ‘It is indeed mon ami Hastings!’

‘Poirot!’ I exclaimed.

I turned to the pony-trap.

‘This is a very pleasant meeting for me, Miss Cynthia. This is my old friend, Monsieur Poirot, whom I have not seen for years.’

‘Oh, we know Monsieur Poirot,’ said Cynthia gaily.

‘But I had no idea he was a friend of yours.’

‘Yes, indeed,’ said Poirot seriously. ‘I know Mademoiselle Cynthia. It is by the charity of that good Mrs Inglethorp that I am here.’ Then, as I looked at him inquiringly: ‘Yes, my friend, she had kindly extended hospitality to seven of my country-people who, alas, are refugees from their native land. We Belgians will always remember her with gratitude.’

Poirot was an extraordinary-looking little man. He was hardly more than five feet four inches, but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandified little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police. As a detective, his flair had been extraordinary, and he had achieved triumphs by unravelling some of the most baffling cases of the day.

He pointed out to me the little house inhabited by him and his fellow Belgians, and I promised to go and see him at an early date. Then he raised his hat with a flourish to Cynthia and we drove away.

‘He’s a dear little man,’ said Cynthia. ‘I’d no idea you knew him.’

‘You’ve been entertaining a celebrity unawares,’ I replied.

And, for the rest of the way home, I recited to them the various exploits and triumphs of Hercule Poirot.

We arrived back in a very cheerful mood. As we entered the hall, Mrs Inglethorp came out of her boudoir. She looked flushed and upset.

‘Oh, it’s you,’ she said.

‘Is there anything the matter, Aunt Emily?’ asked Cynthia.

‘Certainly not,’ said Mrs Inglethorp sharply. ‘What should there be?’ Then catching sight of Dorcas, the parlourmaid, going into the dining-room, she called to her to bring some stamps into the boudoir.

‘Yes, m’m.’ The old servant hesitated, then added diffidently: ‘Don’t you think, m’m, you’d better get to bed? You’re looking very tired.’

‘Perhaps you’re right, Dorcas—yes—no—not now. I’ve some letters I must finish by post-time. Have you lighted the fire in my room as I told you?’

‘Yes, m’m.’

‘Then I’ll go to bed directly after supper.’

She went into her boudoir again, and Cynthia stared after her.

‘Goodness gracious! I wonder what’s up?’ she said to Lawrence.

He did not seem to have heard her, for without a word he turned on his heel and went out of the house.

I suggested a quick game of tennis before supper and, Cynthia agreeing, I ran upstairs to fetch my racquet.

Mrs Cavendish was coming down the stairs. It may have been my fancy, but she, too, was looking odd and disturbed.

‘Had a good walk with Dr Bauerstein?’ I asked, trying to appear as indifferent as I could.

‘I didn’t go,’ she replied abruptly. ‘Where is Mrs Inglethorp?’

‘In the boudoir.’

Her hand clenched itself on the banisters, then she seemed to nerve herself for some encounter, and went rapidly past me down the stairs across the hall to the boudoir, the door of which she shut behind her.

As I ran out to the tennis court a few moments later, I had to pass the open boudoir window, and was unable to help overhearing the following scrap of dialogue. Mary Cavendish was saying in the voice of a woman desperately controlling herself: ‘Then you won’t show it to me?’

To which Mrs Inglethorp replied:

‘My dear Mary, it has nothing to do with that matter.’

‘Then show it to me.’

‘I tell you it is not what you imagine. It does not concern you in the least.’

To which Mary Cavendish replied, with a rising bitterness: ‘Of course, I might have known you would shield him.’

Cynthia was waiting for me, and greeted me eagerly with:

‘I say! There’s been the most awful row! I’ve got it all out of Dorcas.’

‘What kind of row?’

‘Between Aunt Emily and him. I do hope she’s found him out at last!’

‘Was Dorcas there, then?’

‘Of course not. She “happened to be near the door”. It was a real old bust-up. I do wish I knew what it was all about.’

I thought of Mrs Raikes’s gipsy face, and Evelyn Howard’s warnings, but wisely decided to hold my peace, whilst Cynthia exhausted every possible hypothesis, and cheerfully hoped, ‘Aunt Emily will send him away, and will never speak to him again.’

I was anxious to get hold of John, but he was nowhere to be seen. Evidently something very momentous had occurred that afternoon. I tried to forget the few words I had overheard; but, do what I would, I could not dismiss them altogether from my mind. What was Mary Cavendish’s concern in the matter?

Mr Inglethorp was in the drawing-room when I came down to supper. His face was impassive as ever, and the strange unreality of the man struck me afresh.

Mrs Inglethorp came down at last. She still looked agitated, and during the meal there was a somewhat constrained silence. Inglethorp was unusually quiet. As a rule, he surrounded his wife with little attentions, placing a cushion at her back, and altogether playing the part of the devoted husband. Immediately after supper, Mrs Inglethorp retired to her boudoir again.

‘Send my coffee in here, Mary,’ she called. ‘I’ve just five minutes to catch the post.’

Cynthia and I went and sat by the open window in the drawing-room. Mary Cavendish brought our coffee to us. She seemed excited.

‘Do you young people want lights, or do you enjoy the twilight?’ she asked. ‘Will you take Mrs Inglethorp her coffee, Cynthia? I will pour it out.’

‘Do not trouble, Mary,’ said Inglethorp. ‘I will take it to Emily.’ He poured it out, and went out of the room carrying it carefully.

Lawrence followed him, and Mrs Cavendish sat down by us.

We three sat for some time in silence. It was a glorious night, hot and still. Mrs Cavendish fanned herself gently with a palm leaf.

‘It’s almost too hot,’ she murmured. ‘We shall have a thunderstorm.’

Alas, that these harmonious moments can never endure! My paradise was rudely shattered by the sound of a well-known, and heartily disliked, voice in the hall.

‘Dr Bauerstein!’ exclaimed Cynthia. ‘What a funny time to come.’

I glanced jealously at Mary Cavendish, but she seemed quite undisturbed, the delicate pallor of her cheeks did not vary.

In a few moments, Alfred Inglethorp had ushered the doctor in, the latter laughing, and protesting that he was in no fit state for a drawing-room. In truth, he presented a sorry spectacle, being literally plastered with mud.

‘What have you been doing, doctor?’ cried Mrs Cavendish.

‘I must make my apologies,’ said the doctor. ‘I did not really mean to come in, but Mr Inglethorp insisted.’

‘Well, Bauerstein, you are in a plight,’ said John, strolling in from the hall. ‘Have some coffee, and tell us what you have been up to.’

‘Thank you, I will.’ He laughed rather ruefully, as he described how he had discovered a very rare species of fern in an inaccessible place, and in his efforts to obtain it had lost his footing, and slipped ignominiously into a neighbouring pond.

‘The sun soon dried me off,’ he added, ‘but I’m afraid my appearance is very disreputable.’

At this juncture, Mrs Inglethorp called to Cynthia from the hall, and the girl ran out.

‘Just carry up my despatch-case, will you, dear? I’m going to bed.’

The door into the hall was a wide one. I had risen when Cynthia did, John was close by me. There were, therefore, three witnesses who could swear that Mrs Inglethorp was carrying her coffee, as yet untasted, in her hand. My evening was utterly and entirely spoilt by the presence of Dr Bauerstein. It seemed to me the man would never go. He rose at last, however, and I breathed a sigh of relief.

‘I’ll walk down to the village with you,’ said Mr Inglethorp. ‘I must see our agent over those estate accounts.’ He turned to John. ‘No one need sit up. I will take the latch-key.’

Chapter 3

The Night of the Tragedy

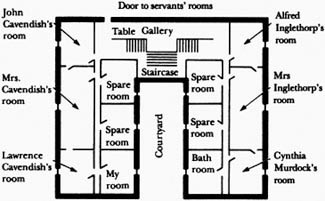

To make this part of my story clear, I append the following plan of the first floor of Styles. The servants’ rooms are reached through the door B. They have no communication with the right wing, where the Inglethorps’ rooms were situated.

It seemed to be the middle of the night when I was awakened by Lawrence Cavendish. He had a candle in his hand, and the agitation of his face told me at once that something was seriously wrong.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked, sitting up in bed, and trying to collect my scattered thoughts.

‘We are afraid my mother is very ill. She seems to be having some kind of fit. Unfortunately she has locked herself in.’

‘I’ll come at once.’

I sprang out of bed, and pulling on a dressing-gown, followed Lawrence along the passage and the gallery to the right wing of the house.

John Cavendish joined us, and one or two of the servants were standing round in a state of awe-stricken excitement. Lawrence turned to his brother.

‘What do you think we had better do?’

Never, I thought, had his indecision of character been more apparent.

John rattled the handle of Mrs Inglethorp’s door violently, but with no effect. It was obviously locked or bolted on the inside. The whole household was aroused by now. The most alarming sounds were audible from the interior of the room. Clearly something must be done.

‘Try going through Mr Inglethorp’s room, sir,’ cried Dorcas. ‘Oh, the poor mistress!’

Suddenly I realized that Alfred Inglethorp was not with us—that he alone had given no sign of his presence. John opened the door of his room. It was pitch dark, but Lawrence was following with the candle, and by its feeble light we saw that the bed had not been slept in, and that there was no sign of the room having been occupied.

We went straight to the connecting door. That, too, was locked or bolted on the inside. What was to be done?

‘Oh, dear, sir,’ cried Dorcas, wringing her hands, ‘whatever shall we do?’

‘We must try and break the door in, I suppose. It’ll be a tough job, though. Here, let one of the maids go down and wake Baily and tell him to go for Dr Wilkins at once. Now then, we’ll have a try at the door. Half a moment, though, isn’t there a door into Miss Cynthia’s room?’

‘Yes, sir, but that’s always bolted. It’s never been undone.’

‘Well, we might just see.’

He ran rapidly down the corridor to Cynthia’s room. Mary Cavendish was there, shaking the girl—who must have been an unusually sound sleeper—and trying to wake her.

In a moment or two he was back.

‘No good. That’s bolted too. We must break in the door. I think this one is a shade less solid than the one in the passage.’

We strained and heaved together. The framework of the door was solid, and for a long time it resisted our efforts, but at last we felt it give beneath our weight, and finally, with a resounding crash, it was burst open.

We stumbled in together, Lawrence still holding his candle. Mrs Inglethorp was lying on the bed, her whole form agitated by violent convulsions, in one of which she must have overturned the table beside her. As we entered, however, her limbs relaxed, and she fell back upon the pillows.

John strode across the room and lit the gas. Turning to Annie, one of the housemaids, he sent her downstairs to the dining-room for brandy. Then he went across to his mother whilst I unbolted the door that gave on the corridor.

I turned to Lawrence, to suggest that I had better leave them now that there was no further need of my services, but the words were frozen on my lips. Never have I seen such a ghastly look on any man’s face. He was white as chalk, the candle he held in his shaking hand was sputtering on to the carpet, and his eyes, petrified with terror, or some such kindred emotion, stared fixedly over my head at a point on the further wall. It was as though he had seen something that turned him to stone. I instinctively followed the direction of his eyes, but I could see nothing unusual. The still feebly flickering ashes in the grate, and the row of prim ornaments on the mantelpiece, were surely harmless enough.

The violence of Mrs Inglethorp’s attack seemed to be passing. She was able to speak in short gasps.

‘Better now—very sudden—stupid of me—to lock myself in.’

A shadow fell on the bed and, looking up, I saw Mary Cavendish standing near the door with her arm around Cynthia. She seemed to be supporting the girl, who looked utterly dazed and unlike herself. Her face was heavily flushed, and she yawned repeatedly.

‘Poor Cynthia is quite frightened,’ said Mrs Cavendish in a low clear voice. She herself, I noticed, was dressed in her white land smock. Then it must be later than I thought. I saw that a faint streak of daylight was showing through the curtains of the windows, and that the clock on the mantelpiece pointed to close upon five o’clock.

A strangled cry from the bed startled me. A fresh access of pain seized the unfortunate old lady. The convulsions were of a violence terrible to behold. Everything was confusion. We thronged round her, powerless to help or alleviate. A final convulsion lifted her from the bed, until she appeared to rest upon her head and her heels, with her body arched in an extraordinary manner. In vain Mary and John tried to administer more brandy. The moments flew. Again the body arched itself in that peculiar fashion.

At that moment, Dr Bauerstein pushed his way authoritatively into the room. For one instant he stopped dead, staring at the figure on the bed, and, at the same instant, Mrs Inglethorp cried out in a strangled voice, her eyes fixed on the doctor:

‘Alfred—Alfred –’ Then she fell back motionless on the pillows.

With a stride, the doctor reached the bed, and seizing her arms worked them energetically, applying what I knew to be artificial respiration. He issued a few short sharp orders to the servants. An imperious wave of his hand drove us all to the door. We watched him, fascinated, though I think we all knew in our hearts that it was too late, and that nothing could be done now. I could see by the expression on his face that he himself had little hope.

Finally he abandoned his task, shaking his head gravely. At that moment, we heard footsteps outside, and Dr Wilkins, Mrs Inglethorp’s own doctor, a portly, fussy little man, came bustling in.

In a few words Dr Bauerstein explained how he had happened to be passing the lodge gates as the car came out, and had run up to the house as fast as he could, whilst the car went on to fetch Dr Wilkins. With a faint gesture of the hand, he indicated the figure on the bed.