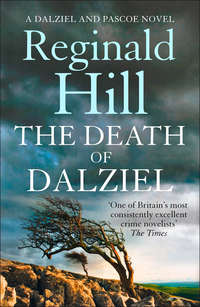

The Death of Dalziel: A Dalziel and Pascoe Novel

Geoff B snorted incredulously, but that was to be expected. It was Geoff O’s disappointed frown that Andre focused on.

He said, ‘War’s like fishing. Hours of empty fucking tedium punctuated by moments so crowded they burst at the seams. Learn to enjoy the emptiness. Now, I’m going to pack up before these fucking midges chew my face off. I’ll be in touch.’

He rose and began to reel in his line.

Geoff B said, ‘Tell Hugh, if that cop dies, I’m out. I’m serious.’

‘Let’s hope the poor sod makes it then,’ said Andre indifferently. ‘See you.’

The couple started to walk away. Geoffrey O glanced back. Andre gave a conspiratorial wink but got nothing in return.

Didn’t bother him.

What did bother him was the weight of the discarded backpack.

He checked no one was close then opened it.

Like he’d thought, one weapon missing.

He looked after the two Geoffreys. No prize for guessing which one had hung on.

He recalled a training sergeant once saying to him, ‘You’ve earned yourself a big kiss for keenness, a big bollocking for stupidity. Which do you want first, son?’

He smiled, dropped the backpack into his basket, slung it over his shoulder, gathered up the rest of his gear and set off along the tow path.

6 blue smartie

Peter Pascoe was still having trouble with time.

He opened his eyes and Ellie was there.

‘Hi,’ he said.

‘Hi,’ she said. ‘Pete, how are you?’

‘Fine, fine,’ he said.

He blinked once and her hair turned gingery as she aged ten years and put on a Scottish accent.

‘Mr Pascoe. Sandy Glenister. Feel up to a wee chat?’

‘Not with you,’ said Pascoe. ‘Sod off.’

He blinked again and the face rearranged itself into something like a Toby jug whose glaze had gone wrong.

‘Wieldy,’ said Pascoe. ‘Where’s Ellie?’

‘At home making Rosie’s tea, I expect. She’ll be back later. How are you doing?’

‘I’m fine. What am I doing here? Oh shit.’

Wield saw Pascoe’s face spasm with remembered pain as he answered his own question.

‘Andy, how’s Andy?’ he demanded, trying to push himself upright.

Wield pressed the button which raised the back of the bed by thirty degrees.

‘Intensive Care,’ he said. ‘He’s not come round yet.’

‘Well, what do they expect?’ demanded Pascoe. ‘It’s only been .. a couple of hours?’

His assertion turned to interrogation as he realized he’d no idea of the time.

‘Twenty-four,’ said Wield. ‘A bit more. It’s four o’clock, Tuesday afternoon.’

‘As long as that? What’s the damage?’

‘With Andy? Broken leg, broken arm, several cracked ribs, some second-degree burns, multiple contusions and lacerations from the blast, loss of blood, ruptured spleen, other internal damage whose extent isn’t yet apparent—’

‘So, nothing really serious then,’ interrupted Pascoe.

Wield smiled faintly and said, ‘No, not for Andy. But till he wakes up…’

He left the sentence unfinished.

‘Twenty-four hours is nothing,’ said Pascoe. ‘Look at me.’

‘You’ve been back with us a lot longer than that,’ said Wield. ‘Bit woozu maybe with all the shit they pumped into you, but making sense mostly. You don’t think Ellie would have taken off if you’d still been comatose?’

‘I’ve spoken with Ellie then?’

‘Aye. Don’t you remember?’

‘I think I recall saying hi.’

‘Is that all? You’d best hope you didn’t make a deathbed confession,’ said Wield.

‘And there was someone else—ginger hair, Scots accent, maybe the matron. Or did I dream that?’

‘No. That would be Chief Superintendent Glenister from CAT. I was there when she turned up.’

‘You were? Did I say much to her?’

‘Apart from “sod off”, you mean? No. That was it.’

‘Oh hell,’ said Pascoe.

‘Not to worry. She didn’t take offence. In fact, she’s sitting outside in the waiting room. You’ve not asked what’s wrong with you.’

‘With me?’ said Pascoe. ‘Good point. Why am I in here? I feel fine.’

‘Just wait till the shit wears off,’ said Wield. ‘But they reckon you were lucky. Contusions, abrasions, few muscle tears, twisted knee, couple of cracked ribs, concussion. Could have been a lot worse.’

‘Would have been if I hadn’t had Andy in front of me,’ said Pascoe grimly. ‘What about Jennison and Maycock?’

‘Joker reckons he’s gone deaf but his mates say he were always a bit hard of hearing when it came to his round. Their cars are a write-off though. Andy’s too.’

‘What about Number 3? Was there anyone in there?’

‘I’m afraid so. Three bodies, they reckon. At least. They’re still trying to put them together. No more detail. The CAT lads are going over the wreckage with a fine-tooth comb, and they’re not saying much to anyone—and that includes us. Of course, they’ve got a key witness.’

‘Have they? Oh God. You mean Hector?’

‘Right. Glenister spent an hour or so with him. Came out looking punch-drunk.’

‘Hector did?’

‘No. He always looks punch drunk. I mean Glenister. I’d best let her know you’re sitting up and taking notice.’

‘Fine. Wieldy, do a check on Andy, will you? You know what they’re like in these places, getting good info’s harder than getting your dinner wine properly chambré.’

‘I’ll see what I can do,’ said Wield. ‘Take care.’

He left and Pascoe eased himself properly upright in the bed, trying to assess what he really felt like. There didn’t seem to be many parts of his body which didn’t give a retaliatory twinge when provoked, but, ribs apart, nothing that threatened much beyond discomfort. He wondered if he could get out of bed without assistance. He had got himself sitting upright and was pushing the bed sheet off his legs preparatory to swinging them round when the door opened and the ginger woman came in.

‘Glad to see you’re feeling better, Peter,’ she said, ‘but I think you should stay put a wee while longer. Or was it a bed pan you wanted?’

‘No, I’m fine,’ said Pascoe, pulling the sheet back up.

‘That’s OK then. Glenister. Chief Super. Combined Anti-Terrorism unit. We met briefly earlier, you probably don’t remember.’

‘Vaguely, ma’am,’ said Pascoe. ‘In fact I seem to recall being a bit rude…’

Glenister said, ‘Think nothing of it. Rudeness is good, it needs a working mind to be rude. I’d just been interviewing Constable Hector for the second time. I couldn’t believe the first, but it didn’t get any better. Is it just shock, or is that poor laddie always as unforthcoming?’

‘Expressing himself isn’t his strongest point,’ said Pascoe.

‘So you’re saying that what I’ve got out of him is probably as much as I’m likely to get?’ said Glenister. ‘His descriptions of the men he saw are, to say the least, sketchy.’

‘He does his best,’ said Pascoe defensively. ‘Anyway, surely it’ll be DNA, fingerprints, dental records, that are going to identify the poor devils in there?’

‘Aye, we should be able to find enough of them for that,’ said Glenister.

She was mid to late forties, Pascoe guessed, full figured to the point where she fitted her tweed suit comfortably but if she didn’t cut down on the deep-fried Mars Bars, she’d soon have to upsize. She had a pleasant friendly smile which lit up her round slightly weather-beaten face and put a sparkle into her soft brown eyes. If she’d been a doctor he would have felt immensely reassured.

Pascoe said, ‘You’ll want to debrief me, ma’am.’

Glenister smiled.

‘Debrief? I see you’re very with it here in Mid-Yorkshire. Me, I’m too old a parrot to learn new jargon. A full written report would be nice when you’re up to it. All I want now is a wee preliminary chat.’

She pulled a chair up to the bedside, sat down, produced a mini-cassette recorder from the shoulder bag she was carrying, and switched it on.

‘In your own words, Peter. All right to call you Peter? My friends call me Sandy.’

Trying to work out if this were an invitation or a warning, Pascoe launched into an account of his part in the incident, with some judicious editing, in the interest of clarity and brevity he told himself.

‘That’s good,’ said Glenister, nodding approval. ‘Succinct, to the point. Just what I need for the record.’

She pressed the off button on the recorder, sat back in her chair and took a tube of Smarties out of her shoulder bag.

‘Help yourself,’ she said. ‘So long as it’s not blue.’

‘No thanks,’ said Pascoe.

‘Wise man,’ she said. ‘I started on the sweeties when I stopped the ciggies. When I realized five bars of fruit-and-nut a day were going to kill me as surely as forty fags, I tried to go cold turkey and that nearly had me back on the nicotine. Now I treat myself to a Smartie whenever the urge comes on. Just the one. Except if it’s a blue one. Then I can have another. God knows what I’ll do now they’re stopping the blue ones.’

She gave him that attractive smile, mocking herself. She really should have been a doctor, thought Peter. With a bedside manner like this, she could have sold urine samples at a guinea a bottle.

‘Now let’s stray off the record, Peter,’ she said, popping one of the tiny sweets into her mouth (a yellow one, he noticed) and settling herself more comfortably into her chair. ‘Just you and me. Thoughts and impressions this time. And maybe just a wee bit more detail. For a start, why were you really there?’

‘I told you. Inspector Ireland rang me and I went to assist.’

‘And why did Paddy Ireland ring you?’

‘Because of my negotiating experience, I suppose,’ said Pascoe. But even as he spoke he was registering the Paddy as a gentle reminder that Glenister had already interviewed the inspector.

‘And because I think he felt that, as the video shop had been flagged by you people, Mr Dalziel might be grateful for some assistance,’ he added.

‘And was he?’

‘I think so.’

‘But he hadn’t contacted you himself?’

‘He wouldn’t care to disturb me on my day off,’ said Pascoe.

‘A most considerate man then. I gather he even offered to obtain refreshment for the people inside Number 3.’

So she knew about the bit of knockabout with the bullhorn. Hector. Or Jennison. Or Maycock. Why wouldn’t they describe exactly what had happened? Even if they’d tried to play it down, they’d have been easy meat for this bedside manner.

He said, ‘Yes, Mr Dalziel did try to make contact with anyone who might be inside the shop.’

‘Who “might” be? You had doubts?’

‘Our information seemed a bit vague.’

‘Vague? Not quite with you there. Foot patrol sees an armed man in Number 3. Reports it to the car-patrol officers who pass it on to the duty inspector who alerts the station commander. Don’t see where the vagueness lies. All by the book so far.’

‘Yes, and that’s the way it continued,’ said Pascoe firmly. ‘Knowing that the property was flagged, Mr Dalziel made sure your people were alerted then proceeded to Mill Street as instructed.’

‘As instructed?’ Glenister chuckled.

Chuckling was a dying art, thought Pascoe; genuine chuckling that was, not just that pretence of suppressed mirth which politicians still use to make or, more often, avoid a point. But Glenister’s chuckle was the real McCoy.

‘My understanding of his instructions,’ continued the superintendent, ‘is that he was told to withdraw any police vehicles from Mill Street, establish blocks at its ends, maintain observation from a distance, and make no attempt to approach Number 3. Which bit of his instructions would you say Mr Dalziel followed, Peter?’

‘I don’t know because I’ve only your say-so that that’s what they were,’ retorted Pascoe, consigning to the recycle bin what the Fat Man had told him as they squatted behind the car. ‘But, if we’re portioning out responsibility, what I’m certain your instructions didn’t contain was any reference to the fact that there was enough explosive in the place to blow up the whole bloody terrace! But I guess you didn’t know that, else why would it only have a bottom-level flagging?’

Glenister shook her head and said sadly, ‘You’re so right, Peter. We should have known that. But you’re completely wrong if you think I’m here to offload blame. Wrists will be slapped at CAT, have no fear. If your Mr Dalziel got it wrong, then we got it wrong just as much, and he’s paid a far higher price. I hope he comes through but the signs aren’t good. So the only person I’ve got who can give me a close-up account of what took place is you. All I want is to be absolutely sure about everything you saw during your time outside Number 3 Mill Street.’

‘That’s easy,’ said Pascoe. ‘From my arrival to the explosion, I saw absolutely no sign of life in the house, or anywhere else in the terrace. Full stop.’

‘Fine, that’s good enough for me,’ said Glenister, standing up and offering her hand. ‘We’ll talk again when you’re back on your feet. I hope that will be very soon.’

‘But can’t you tell me what you think happened in there?’ demanded Pascoe, holding on to the hand.

Glenister hesitated, then said, ‘Why not? I hear you’re a discreet man. In fact you might turn vain if you knew how highly you’re rated. Quite the blue Smartie yourself.’

She smiled at her joke. Pascoe gave her a token flicker and said, ‘So?’

‘We had the shop flagged as a meeting place, at best a casual message centre, for a group who showed little inclination to move from dialectic to destruction. At some time in the past few days a decision must have been taken to upgrade it to a storehouse for explosive in preparation for an event. We had some non-specific intelligence that something big was being planned in the north.’

‘Like blowing up Mill Street?’ said Pascoe incredulously. ‘Not exactly the Houses of Parliament, is it?’

‘I said Number 3 was just the storehouse,’ said Glenister. ‘Though it won’t have escaped your notice that the terrace backs on to the embankment carrying the main London line, and your fair city is being honoured with a royal visit the week after next. Be that as it may, suddenly there is a large quantity of explosive on site, harmless enough when being handled by experts. But, as I say, the group who had hitherto made use of the shop were anything but experts. Your Constable Hector disturbed them, your Mr Dalziel made them panic. Perhaps they were simply trying to conceal the explosive more thoroughly and something went wrong. Or perhaps when they saw you and Mr Dalziel moving forward, they weighed a long night in an interview room with you against an eternity in Paradise with a martyr’s promised houris. Either way, boom!’

She gently disengaged her hand, which Pascoe now realized he’d been clinging on to like an ancient mariner eager for a chat.

‘You take care of yourself now, Peter,’ said Glenister. ‘The Force can’t spare its blue Smarties in these troubled times. I hope you’re back at work really soon.’

She went out of the room. Pascoe stared at the closed door for a while, then shoved back the sheet and swung his legs on to the floor. He was surprised to find how weak this simple movement left him and he was still sitting on the bed, nerving himself to test his knee, when Wield came in.

‘Where do you think you’re going?’ demanded the sergeant.

‘I’m going to see Andy.’

‘Not now you’re not,’ said Wield.

Something in his tone alerted Pascoe that the sergeant wasn’t just coming the nurse-substitute.

‘Why? What’s happened?’ he demanded.

‘I asked the ward sister to check how Andy was doing in Intensive Care,’ said Wield. ‘She was talking to someone there when all hell broke loose at the other end of the phone. Pete, his heart stopped. They’ve got the crash team working on him now, but from what the sister said, it’s not looking good. Pete, we need to face it. This could be the end for Fat Andy.’

7 dancing with death

Andy Dalziel is in the Mecca Ballroom, locked in a tango with Tottie Truman from Donny.

He feels as light as a feather. His feet hardly seem to be in contact with the floor, his muscles responding to every modulation of the music as if the notes were vibrating along his arteries rather than through his ears. And he can feel the blood pulsing through Tottie’s veins in a perfect counterpoint to his own rhythms as they move inexorably towards that blissfully explosive moment of complete fusion…

But not on the dance floor! It’s all a question of timing. In search of delay, he makes his mind step back and take in his surroundings.

The Mirely Mecca has changed a lot since his last visit which was…he can’t recall when. Never mind. The ceiling’s higher now and the soaring windows, spring-bright with coloured glass, wouldn’t disgrace a cathedral. The walls are lined with long tables, covered in white linen cloths on which rest a royal banquet of everything he loves—on one table crowns of lamb, barons of beef, loins of pork ridged with crackling, honey-glazed hams; on another roasted geese, Christmas turkeys, duck with cherries, pheasant adorned with their own feathers; on a third whole salmon, pickled herring, mountain ranges of oysters and mussels. Yet another is crowded with desserts: bread-and-butter pudding, rhubarb crumble, Spotted Dick, and his childhood favourite, Eve’s Pudding.

And there, by a table laden with bottles of every kind of malt whisky he’d ever tasted, stands Peter Pascoe, an open bottle of Highland Park in one hand and in the other a king-size crystal tumbler full to the brim which he is holding out in smiling invitation…

Later, lad, he mouths. Later. First things first. Dance till the music reaches its climax, then straight out of the door into that dark alcove at the end of the corridor to reach his and hers…

After which, being a gentleman, he’ll wait a decent interval of mebbe a minute and a half before heading back inside for another helping of Eve’s Pudding…

But just as he begins to wonder if he can hold out any longer, the music changes, accelerating from the sensuous pulse of the tango into the mad whirl of a Viennese waltz. His muscles obey the new commands effortlessly though his mind wonders what the fuck the band leader’s playing at. Round and round and round he spins, till the high walls and coloured windows and laden tables retreat to a blur of Arctic whiteness and Tottie’s body, which during the tango had been a comfortable armful of warm softness moulding itself ever closer to his, begins to feel like a sackful of old bones.

Now he too is beginning to feel tired, as if age and exertion and all the excesses of a life spent in mad pursuit of God knows what are at last catching up with him. He wants to rest. Surely Tottie would want to sit this one out too? He nuzzles his lips against her ear to whisper the suggestion, but he can’t find it. The cheek pressed against his no longer feels soft and warm but cold and hard and smooth.

He moves his head back to look into his partner’s face. Instead of the lustrous brown bedroom eyes of Tottie Truman, he finds himself peering into the deep shadowy sockets of a skull whose toothy leer and vacant gaze have something familiar about them.

Then recognition dawns.

Dalziel laughs.

‘Hector, lad,’ he cries. ‘I always said tha’d be the death of me, but I never meant it so literal!’

The skeletal figure does not reply but its grip tightens round the Fat Man’s broad frame and he finds his weary legs being urged into an even wilder dance which feels as if it will only end when those bony arms have squeezed out of him everything that makes up the life force—sun and wind and air and rain, good grub and mellow whisky, light and laughter—and whirled what little remains away into some icy eternity.

For a moment he is lost. He, the great Dalziel, who on his day has danced from dusk to dawn and then washed down the Full British Breakfast with a tumbler of whisky, has no strength to resist as Death, or Hector, bears him off to oblivion.

Then at the very point of submission, something happens.

New resolve seems to course through his weary limbs like an electric shock. Then another, even stronger. A third…a fourth…a fifth…

Sod this for a lark! he thinks. I’ll give this bugger a run for his money afore I let him dance me off my feet!

Pressing Death or Hector even closer to his chest, he rises on to his toes and goes whirling round the room, once more the leader not the led, faster and faster, till he leaves the wild music trailing in his wake. And this time, instead of blurring out his surroundings, the speed of the dance seems to bring them back into focus. First the high windows with their multi-coloured lights, and then white-clothed tables laden with provender, and finally he becomes aware that the brittle bones in his arms are once more clothed in the warm and yielding flesh of Tottie Truman from Donny.

8 blame

‘He’s stable now, but it was a close-run thing,’ said Dr John Sowden. ‘With anyone else I’d have called it after the fifth shock. But I looked down at the fat old bastard lying there and I thought, I’m not going to risk being haunted by you! And I gave him one more go.’

Dr Sowden was an old acquaintance of the Pascoes, a relationship which had started way back in a close encounter with Andy Dalziel under suspicion of causing death by drunk driving.

‘And that did the trick?’ said Ellie Pascoe.

‘It started his heart beating again. Which is something, but don’t get your hopes up. He’s only back to where he was. Still showing no sign of regaining consciousness. And we’ve no idea what state he’ll be in if and when that happens. You, Peter, on the other hand are looking remarkably spry, considering.’

‘So when can I go home?’ said Pascoe. ‘I feel fine.’

It was almost true. The anxiety caused by the news about Fat Andy, the relief at hearing they’d got him back, and the pleasure of having Ellie sitting on his bed, had seemed to combine as a sort of tonic. John Sowden ought to be showering praise on him for his resilience rather than pursing his lips.

‘Let’s see how you are in a couple of days,’ said the doctor dismissively. ‘Ellie, nice to see you again. Make sure he behaves himself.’

He went out.

‘John ought to brush up his bedside manner, don’t you reckon?’ said Pascoe.

‘I think he’s a bit worried there may be some delayed emotional reaction,’ said Ellie carefully.

‘He’s been talking to you, has he? Don’t tell me he actually used those tired old words posttraumatic stress disorder!’ Pascoe laughed harshly. ‘Listen, if ever I start feeling sorry for myself, I just have to think of Andy lying up there in a coma.’

Ellie took his hand and squeezed it.

‘I know, I know,’ she said. ‘I often wished the earth would open up and swallow the fat bastard, but it’s almost impossible to imagine a world without Andy, isn’t it?’

‘Not almost,’ said Pascoe. ‘You said you’d seen Cap. How’s she taking it?’

‘Hard to say. She once told me that the only worthwhile thing she learned at St Dot’s Academy was to deal with crisis and catastrophe by not letting it mark your upper crust. While us plebs scream and shout and run about, people of Cap’s class maintain an even keel and look to the practicalities.’

Pascoe smiled at ‘us plebs’. Ellie’s family were irremediably petit bourgeois despite all her efforts to downgrade them to acquire street cred in the class war. By contrast Cap Marvell, while making no effort to deny her upper-class background and education, had been much more successful in her efforts to disoblige her old connections. Having a secret weapon like Andy Dalziel you could produce at will can’t have been a disadvantage either.

Pascoe liked her in a cautious kind of way. She was good for Dalziel emotionally and intellectually and, one presumed, physically, but her readiness to strain the law in pursuit of her animal rights causes was a ticking bomb for a working cop. On the other hand it struck him as one of God’s better jokes that after many years of heavy-handed jesting about Ellie’s unbecoming behaviour as a political activist, Dalziel should find himself hoist with the same petard.