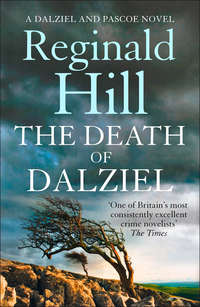

The Death of Dalziel: A Dalziel and Pascoe Novel

They went straight into a room with twenty chairs set in four rows of five before a large TV screen. Pascoe and Glenister took seats in the second row. He glanced round to see Freeman in the row behind. Was this indicative of a pecking order? And if so did they peck from the front as in a theatre or from the rear as in a cinema?

As if in answer, the man sitting directly in front of him turned round and smiled at him. Pascoe recognized him instantly. His name was Bernie Bloomfield, his rank was commander and the last time Pascoe saw him, he’d been giving a lecture on criminal demography at an Interpol conference. If he hadn’t pursued a police career, he might well have filled the gap left by that most sadly missed of British actors, Alastair Sim.

‘Peter, good to see you again,’ said Bloomfield.

For a moment Pascoe was flattered, then he remembered his security label.

‘You too, sir,’ he said. ‘Didn’t realize you were in charge here.’

‘In charge?’ Bloomfield smiled. ‘Well, in this work we like to keep in the shadows. How’s my dear old friend Andy Dalziel doing?’

‘Holding on, sir.’

‘Good. I’d expect no less. A shame, a great shame. Andy and I go way, way back. We can ill spare such good men. But it’s a pity it was one of your less indispensable officers who was first on the scene. Constable…what was his name?’

‘Hector, sir,’ said Glenister.

‘That’s it. Hector. From what I read, we’re likely to get more feedback from the speaking clock. “Sort of funny and not a darkie”, isn’t that the gist of his contribution?’

There was a ripple of laughter, and Pascoe realized that their conversation had moved from private chat to public performance. He felt a surge of irritation. Only here two minutes and already he was having to defend Hector in front of a bunch of sycophants who clearly felt very superior to your common-or-garden provincial bobby.

Time to lay down the same markers he’d already put in place with Glenister.

He said with emphatic courtesy, ‘With respect, sir, as I’ve told the superintendent, I think it would be silly to underestimate Constable Hector’s evidence. While it’s true that in his case the picture may take a bit longer to come together, what he does notice usually sticks and emerges in a useful form eventually. What he’s given us so far has proved right, hasn’t it? In fact, with respect, isn’t most of what we know about what happened in Mill Street that day down to Hector rather than CAT?’

This defensive eulogium, which in the Black Bull would have had colleagues corpsing, reduced the audience here to silence. Or perhaps they were simply waiting to see how Bloomfield would deal with this uppity newcomer who’d just called him silly and his unit inefficient.

The commander gave Pascoe that Alastair Sim smile which indicates he knows a lot more than you’re saying.

‘That’s very reassuring, Peter,’ he said. ‘Or are you just being loyal?’

‘Never back down,’ was the Fat Man’s advice. ‘Especially when you’re not sure you’re right!’

Pascoe said firmly, ‘Loyalty’s nothing to do with it, sir. You find us a live suspect and I’m sure you’ll be able to rely on Hector for identification.’

‘I’m glad to hear it. Now I think it’s time to get our show on the road.’

He rose to his feet and let his gaze drift down the rows.

‘Good day to you all,’ he said. ‘What you are about to see is a tape played on Al Jazeera television earlier today. It isn’t pretty, but no point closing your eyes. Some of you will need to see it many times.’

He sat down and the lights dimmed.

The tape lasted about sixty seconds, but even to sensibilities toughened by a gruelling job as well as by general exposure to the graphic images shown most nights on news programmes, not to mention the computer-generated horrors of the modern cinema, the unforgiving minute seemed to stretch for ever.

There was no soundtrack. Someone said ‘Jesus!’ into the silence.

After a long moment, another man stood up in the front row. Fiftyish, balding, wearing a leather patched jacket, square-ended woollen tie and Hush Puppies, he spoke with the clipped rapidity of a nervous schoolmaster saying grace before he is interrupted by the clatter of forks against plates. His label said he was Lukasz Komorowski.

‘This is without doubt Said Mazraani. His body was found in his flat this morning with the head severed, preliminary examination suggests by three blows as illustrated in the video clip. The chair, carpet and background in the tape sequence correspond precisely with what was found at the flat. There was a second body in the flat. This belonged to a man called Fikri Rostom who, as you will hear, Mazraani introduced as his cousin. Rostom, a student at Lancaster University, was shot in the head.’

He paused for breath.

Glenister said, ‘What’s the writing say?’

‘It says Life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.’

He paused again, this time like a schoolmaster waiting for exegesis. Pascoe knew it was biblical, probably Old Testament, but could go no further. Andy Dalziel would have given them chapter and verse. He claimed his disconcerting familiarity with Holy Writ had been acquired via a now largely neglected pedagogic technique which involved his RK teacher, a diminutive Welshman full of hwyl and hiraeth, boxing his ears with a leather-bound Bible each time he forgot his lesson.

Pascoe found himself blinking back tears at the same time as Glenister said, ‘Exodus 21.’

Commander Bloomfield twisted in his chair to look at her.

‘I’m glad to see we’re not yet a completely godless nation,’ he murmured. ‘Do go on, Lukasz.’

Komorowski resumed at a slightly slower pace.

‘Verses 23 to 25; the language is Arabic and the source is a tenth-century translation of the Bible by Rabbi Sa’adiah ben Yosef who was the gaon, or chief sage, of the Torah academy at Sura. The Torah is an Hebraic word meaning the revealed will of God, in particular Mosaic law as expounded in the Pentateuch, which is the first five books of the Old Testament of which Exodus is the second…’

He paused again.

‘Tell us something we don’t know,’ murmured Glenister.

Clearly they educated kids differently in Scotland, thought Pascoe.

Komorowski resumed, ‘Below we find the words In memory of Stanley Coker. Coker, you will recall, was the English businessman taken hostage and subsequently beheaded by the Prophet’s Sword group. The flat and the bodies are currently being examined. Full reports will be issued as soon as they are available. Preliminary post-mortem findings confirm the timetable indicated by our tapes. The bullet recovered from Fikri Rostom was a nine millimetre round almost certainly fired from a Beretta 92 series semi-automatic pistol.’

Pascoe turned to look at Glenister, who continued to stare straight ahead.

‘I have the tape here which gives us the timings,’ continued Komorowski. ‘Mazraani, even if he had not discovered the exact location of our listening device, always assumed he was being overheard. Indeed, as you will hear, he refers to our tape. So he always took the precaution of playing masking music. Here is what we have.’

He raised his index finger and a recording started to play.

First sound was of a door being opened.

‘Tape activated by arrival, we guess, of the alleged cousin,’ said Komorowski.

Music began to play, then a female voice began to sing.

‘Elissa, the Lebanese singer,’ said Komorowski. ‘Fikri seems to have been a fan. We can run on here I think.’

The tape gabbled forward then slowed again to normal speed.

‘Fifteen minutes on, the door opens again, Mazraani arrives, beneath the music we can hear greetings being exchanged,’ said Komorowski. ‘Then the music is turned up louder, suggesting that what they say next they do not wish to be overheard. AV are not hopeful of extracting anything useful from this portion of the tape but will continue to try. A minute later…here it comes…’

The singing suddenly sank to a low background and a click was heard.

‘The intercom. Our killers have rung the door bell downstairs,’ interposed Komorowski rapidly.

Now a voice spoke, educated, urbane.

‘Gentlemen, how can I help you?’

‘Mazraani,’ said Komorowski.

‘Just like a quick word, sir.’

This voice, even though distant and tinny through the intercom, had the unmistakable flat force of authority.

‘By all means. Won’t you come up?’

The sound of a door being opened then a pause, presumably to wait for the newcomers to make their ascent.

‘Evening, Mr Mazraani. And this is…?’

The voice of authority again. Northern. Presumably a linguist could get closer.

‘My cousin, Fikri. He’s staying with me for a few days.’

That’s nice. Anyone else in the flat?’

‘No. Just the two of us.’

‘Mind if we check that? Arch.’

Doors opening and shutting.

‘Clear.’

A third voice. Lighter, tighter. Holding on to control?

‘So now we can perhaps get down to what brings you here. Won’t you introduce yourselves? For the tape?’

The urbanity came close to mockery. Poor bastard, thought Pascoe. He thinks he’s just got the law to deal with.

‘Certainly, sir. I’m called Andre de Montbard. Andy to my friends. And my colleague is Mr Archambaud de St Agnan. He’s got no friends. And this lady singing is, I’d say, the famous Elissa? Compatriot of yours, I believe? Gorgeous girl. Lovely voice and those big amber eyes! I’m a great fan.’

And now the singing was turned up to a volume even higher than before.

Lukasz Komorowski let it run for a moment then made a cut-off gesture and the tape stopped.

‘During the next couple of minutes we believe the killings took place. First the shooting, then the beheading. The killers leave. At eight thirty-nine the Elissa CD stops. Five minutes later the recording stops too and is not reactivated until our team enter this morning. Right. Questions? Observations?’

Glenister began to say something but Pascoe cut across her. Make his presence felt. Show the bastards he wasn’t here just to make up the numbers.

‘Mazraani said “Gentlemen”, plural, when he answered the intercom. Like he knew there was more than one of them.’

‘Your point being…?’

‘My point is it suggests he’d spotted them earlier.’

‘Very likely. Mazraani must have got used to being followed. Even if he didn’t see anyone, he’d assume they were there.’

‘Meaning he’d think these two were yours?’

‘Possibly,’ said Komorowski dismissively. ‘Thank you, Mr Pascoe. Sandy…’

But Pascoe wasn’t done.

‘Then why the hell weren’t they?’ he demanded.

‘Sorry?’

‘Why weren’t there any of your men around? OK, I gather you’d managed to lose track of Mazraani earlier that day. I’d have thought the obvious thing to do was put someone on watch outside his flat. At least that’s the way we’d have done it back in good old-fashioned Mid-Yorkshire CID, despite our staffing problems.’

Komorowski put his hand to his mouth as though to inhibit an over-hasty reply and looked down at Pascoe with a speculative gaze. Presumably he was high enough up the pecking order on the Intelligence half of CAT to feel he didn’t need to take crap from DCIs. Pascoe noticed with distaste that his fingernails were cracked and none too clean.

Commander Bloomfield twisted his long frame in his chair and smiled at Pascoe.

‘If I didn’t know you were one of Andy Dalziel’s boys, I think I’d have guessed,’ he said. ‘Thing is, Peter, despite all this crisis talk, we’re desperately short of manpower here in CAT. Probably in real terms even shorter than you doubtless are in your good old-fashioned CID. Result: we’re continually re-assessing priorities. The chaps on Mazraani lost him. Procedure is report it in, return to base for reassignment. As for watching the flat, why waste men when we’ve got a bug inside? Soon as the tape was checked and we became aware there was activity, we’d have had someone round there.’

‘So when was the tape checked?’ asked Pascoe.

Bloomfield glanced at Komorowski.

‘Midnight that night,’ said the man.

‘So you sent a surveillance team round then?’

‘Well, no,’ admitted Komorowski. ‘There’d been no further activation of the tape after the CD finished playing, so it was assumed the flat was now empty.’

‘While actually it was full of dead people,’ said Pascoe. ‘And didn’t whoever checked the tape out wonder who these two guys—what did they call themselves…?’

‘Andre de Montbard and Archambaud de St Agnan,’ said Glenister, who was looking at Pascoe with the gentle smile of a mother proud of her prodigious son.

‘…which to anyone but the brain-dead sound suspiciously like assumed names—didn’t he wonder who this pair were?’

Komorowski now looked like a schoolteacher cornered by a smart-arse pupil.

‘Or,’ Pascoe went on relentlessly, ‘did he make the same error as Mazraani and assume they were official, maybe because he’d got used to working in an environment where the right hand doesn’t always know what the left is doing?’

A silence followed this question, and in Pascoe’s eyes answered it too.

Then Freeman spoke from behind him.

‘Lukasz,’ he said, ‘if Pete here’s quite finished…’

Pascoe glowered round at him. Teacher’s pet, he thought. Get your boss off the hook, earn brownie points.

He said, ‘I’m done. For now.’

‘Thanks,’ said Freeman. ‘Lukasz, these weird names the killer gave—or rather, the man we assume is the killer gave—do we have anything on them?’

‘Yes, as a matter of fact we do,’ said Komorowski. ‘But first I should draw your attention to an e-message every newspaper, TV news centre and news agency received two days ago. It read: It would appear that a new order of knighthood has been founded on earth.’

He paused as if inviting identification.

When none came he said, ‘Don’t worry. Of the great intellects who run our press, only one recognized it, and that, curiously, was the sports editor of the Voice. He was intrigued enough to mention it to the paper’s Security correspondent, who passed it to us. We put it on file with a question mark. Now I think the question mark can be removed.’

He paused again and Bloomfield said, ‘In your own time, Lukasz.’

‘Thank you, Bernie,’ said Komorowski, as if taking the remark at face value. ‘In fact this is a translation of the opening words of St Bernard of Clairvaux’s Liber ad milites Templi, written at the request of his friend, Hugh de Payens, to define, justify and encourage a new order of knights Hugh and a few others had just founded. These were the Knights Templar, whose initial function was to protect the many pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem. Although the First Crusade had seen the establishment of new Christian states in the region, it was still a dangerous place for the unwary pilgrim, who provided an easy target both for religious zealots and for common thieves. Rapidly, however, the new Order outgrew its founding purpose and evolved into an independent fighting force dedicated to driving the infidels out of the Holy Land. Eventually it became so powerful that it had to be crushed by the very powers of Western Christendom whose values it was formed to defend. But it is its beginnings not its ending that concern us here.’

He paused again and looked around as though anxious for approval.

Bloomfield said, ‘Good, good. And your point, Lukasz?’

‘Besides Hugh de Payens there were eight other founder members of the order, all French noblemen,’ said Komorowski. ‘One is unknown, possibly Hugh Count of Champagne who was de Payens’ liege lord. Two are known only by their Christian names: Rossal and Gondamer. The names of the others are Payen de Montdidier—incidentally, the fact that Payen here and its plural form in the name of the Order’s founder look like medieval forms of modern paien, pagan, seems to be a coincidence.’

Another pause, another glance around as if looking for comment or contradiction. There was none, unless an audible sigh from Bloomfield could be interpreted as either.

‘Now where was I?’ said Komorowski. ‘Oh yes. Montdidier. Then there are two Geoffreys: de St Omer and Bisol. And finally, and for our present purpose, most significantly, there is a knight called Archambaud de St Agnan, and a future Grand Master of the Order whose name is Andre de Montbard.’

2 a pale horse

Hugh de Payens was galloping his grey stallion across a wide green meadow under an ancient castle’s beetling walls. On either side ranks of armed men held their eager mounts under strict control, their restless hooves rising and falling on the same spot, their heaving breasts creating a dark ripple of muscle that ran as far as the eye could see. Cuirasses glinted in the bright summer sun, pennants bearing lions, bears, griffins and dragons, rampant, courant, couchant, fluttered above them, and high over all floated the broad banners which on a lily-white ground bore the symbol of their purpose and their faith, the red cross.

Then a little bell rang and in a trice the castle became an insubstantial ruin, the mounted men and their flags vanished, leaving the rider hacking gently along the edge of a field on a placid grey mare with nothing for company but a few uncurious cows.

He reined in, took out a mobile, accessed Messages and found a single capital X.

He erased it and urged his mount forward into a spinney of beech trees slimming into willow as he approached a narrow but deep and fast-moving stream. On its bank he came to a halt and slackened the rein so that the horse could crop the long grass.

He speed-dialled a number.

‘Bernard.’

‘Hugh.’

‘De Clairvaux.’

‘De Payens.’

Silence. He counted mentally.

one thousand two thousand three thousand

Dead on three seconds the other voice spoke.

Anything less, anything more, and he would have switched off, removed the SIM card, cut it in half with the pair of electrical wire strippers attached to his belt, and hurled the pieces and the phone into the stream.

‘Hugh, the loose end, there’s been a suggestion it might not be so harmless as we thought. I wonder if it wouldn’t be as well to tie it up. Discreetly, of course.’

A moment’s silence then Hugh said, ‘I’m not sure I like the sound of that. It’s not what we’re about.’

‘Of course it isn’t. But in the field sometimes the choice is between collateral damage and protecting our own. Or, let’s not be mealy-mouthed, protecting ourselves.’

‘Our structure protects us.’

‘There are always links. You know me. Andre knows you. The Geoffreys know Andre.’

‘I hope you trust my discretion. I trust Andre. And he says the Geoffreys are reliable.’

‘Are they? From what you reported of Bisol’s reaction to Mill Street, I would have doubts.’

‘He’s concerned about the injured policeman. Removing another as damage limitation isn’t going to make him feel any better.’

‘Properly done, no reason why he should ever know, is there? Look, I don’t like this any more than you do, but I know how easily things can unravel. I’ve already had to put one nosey policeman on a tight rein. The loose end in question seems to be accident prone, so it shouldn’t be too difficult to remove him without arousing either suspicion or further agitating Bisol’s tender conscience. From what you say of him, I imagine Andre would take it in his stride. I leave it with you.’

The phone went dead.

Hugh switched off. His patient horse, alert to signals, raised its head, then resumed cropping the grass as its rider made no movement but sat in thought for a while.

Finally he activated his phone once more, texted an X, and disconnected.

A few moments later the phone rang.

‘Hugh.’

‘Andre.’

‘De Payens.’

‘De Montbard.’

one thousand two thousand three thousand

‘Andre, how are you? I’ve just been talking to Bernard. There’s a little job which sounds very much your cup of tea…’

3 kaffee-klatsch

Two days after Pascoe had gone west, Ellie Pascoe and Edgar Wield met outside the Arts Centre. Wield knew it wasn’t by chance when Ellie, uncomfortable with deception, over-egged her look of surprised pleasure.

She wants to talk about Peter, he guessed, but is worried about looking disloyal.

‘How do, Ellie?’ he said before she could speak. ‘Fancy a coffee at Hal’s?’

He saw he’d stolen her line, and she’d been married to a detective long enough to work out why by the time they climbed up to the mezzanine café-bar in the Arts Centre.

With relief, because she hated masquerade, she took this as an invitation to cut straight to the chase as soon as they’d got their coffee.

‘Have you heard from Peter?’ she asked.

‘Aye.’

‘And what’s he say?’

‘This and that,’ he answered vaguely. ‘Have you not heard yourself?’

‘Of course I have,’ she said indignantly. ‘He rings me every night.’

Every night seemed a large term for the two nights Pascoe had been away.

‘Rings me during the day,’ said Wield. ‘Don’t expect he misses me at night.’

They smiled at each other like the old friends they were.

‘So what’s he talk to you about?’ said Ellie.

‘That and this,’ repeated Wield. ‘Work stuff. You know Pete. Thinks the place is going to fall apart if he’s not there to keep an eye on things.’

Ellie saw that he might have opened things up for her, but he had his loyalties too. This was her call.

She said, ‘I’m a bit worried about him, Wieldy. More than a bit. A hell of a lot. I think he’s got really obsessive about this bomb investigation.’

‘Came close to killing him,’ said Wield. ‘Enough to make you both obsessive.’

‘Meaning, how clear’s my own judgment here?’ interpreted Ellie. ‘Wieldy, if you can put your hand on your heart and tell me he’s fine, that’ll do the trick for me.’

He drank his coffee. His face was as unreadable as ever, but Ellie knew because she’d known it from the start that she wasn’t going to hear much for her comfort.

He said, ‘Wish I could. But it’s not so odd that I can’t. Being close to something like Mill Street doesn’t just go away. I reckon it shook Pete up more than he’ll admit. Since it happened, he’s definitely not been himself. Trouble is, from what I’ve seen of him, what he’s trying to be is Andy Dalziel. The way he deals with people, the way he talks, even, God help us, the way he walks, it’s like he feels he’s got to fill in for Fat Andy. But likely you’ll have noticed?’

‘I noticed something,’ said Ellie unhappily. ‘But he’s a great bottler-up. Stupid sod imagines he’s protecting me and Rosie by clamping down the hatches. He said an odd thing when he went back to work that first time. He said he felt he had to, as if him not being there would lessen the chances of Andy recovering. A sort of sympathetic magic.’

‘Very like,’ said Wield. ‘Look, luv, I don’t think you should worry too much. Either Andy’ll make it and we’ll all get back to normal, or he won’t, and we’ll all get back to normal then too, only it’ll take a bit longer and normal will have changed.’

She’d wanted honesty before comfort. This sounded to her reasonably close to the former and a long way short of the latter.

She said, ‘I just wish he hadn’t gone to Manchester. I suppose we should be grateful to Sandy Glenister for seeing how much it meant to him to stay involved, but I don’t really see how he can be of any use to those CAT people across there…What?’

Wield knew that in the innermost reaches of his mind he had grunted sceptically, but he was certain that nothing in his larynx had uttered even the ghost of an echo of that grunt. Also he had the kind of face which made the Rosetta Stone seem as easy to read as the back of a cornflake packet. ‘Watch his left ear,’ advised Andy Dalziel. ‘It doesn’t help, but it means you don’t have to look at the rest of his face.’