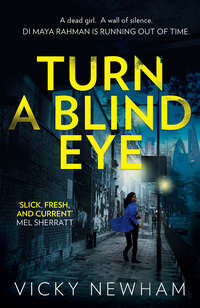

Turn a Blind Eye: A gripping and tense crime thriller with a brand new detective for 2018

I’d clocked Suzie as I was parking and told her to wait for me. I headed over to a uniformed officer who was standing at the main entrance to the school. I’d met PC Li several times.

‘Hi, Shen. Who’s the SIO?’

‘DCI Briscall, but he’s not here. DS Maguire’s over there.’

‘Who?’

‘He’s new. That’s him.’ She pointed at a man with ginger hair and urgent movements.

‘Okay, thanks.’ I surveyed the area outside the cordon. ‘Could you get me a list of everyone here, and their connection to the school?’

‘Sure.’ Shen took out her notepad.

I approached the man she’d gestured to. ‘DS Maguire?’

He whirled round and I was struck by his milky white skin, all the more pronounced by a crew cut.

‘I’m DI Rahman. I was expecting DCI Briscall…’

‘He’s at a meeting with the Deputy Assistant Commissioner. He’s sent me.’ His vowels had a twang, and his sentences rose at the end.

I was trying to think of a polite way of asking how he’d got on the team. ‘I don’t think we’ve met?’

‘I’m a fast-track officer.’

‘Ah.’

‘Don’t worry. I know we aren’t popular. I’m all up to speed.’ He waved his warrant. ‘Done a three-month intensive in West Yorkshire, a sergeant rotation, and passed my exams.’ He stopped there. ‘Aren’t you meant to be on leave?’

‘Until tomorrow, but never mind about that.’ This was a shock, but now wasn’t the time to debate the merits of the Met’s fast-track programme. ‘I’ve just had a call from a local reporter. She said the head’s dead.’ I used my eyes to indicate Suzie, who was holding court with a bunch of parents and locals. ‘If she doesn’t get some facts soon, she’ll make them up. If Briscall’s not coming, you’d better fill me in.’

*

Twenty minutes later, I’d dealt with Suzie James and was in the school canteen with the Murder Investigation Team. With its swimming pool acoustics and tortoise-slow broadband, it wasn’t ideal as a temporary incident room but it was a vast space with plenty of tables and chairs. Twenty-four hours ago I was on a long-haul flight home, and now I was perching at one of the tables by the serving hatch. The surface was sticky and I longed for a decent chair to sit on, rather than the plastic kiddie seats that were bolted to the floor. Round me, the investigation team was gearing up. Colleagues were installing our technology, setting up the HOLMES connection and erecting partition boards. DC Alexej Hayek stood, muscled arms folded and legs apart, bellowing instructions and gesturing, as though he was directing traffic. His clipped Czech accent lent authority to what he thought should go where. With DS Barnes suspended, and Briscall more interested in hob-nobbing with his seniors than covering my post, I wasn’t surprised when he accepted my offer to curtail my leave and appointed me SIO. If any of my colleagues wondered why I was back early from compassionate leave, they knew better than to ask.

I’d been mapping out our main lines of enquiry in my notepad. We were in the golden hour of the investigation, so these were organised round evidence gathering, witness interviews and suspect identification. Our quickest evidence source was going to be social media ring-fencing: once we found out from Facebook and Instagram who was in the school area between 12 noon and 1 p.m., we could target-interview those individuals.

As I surveyed the room, I remembered standing in line at that exact serving hatch, as a nervous eleven-year-old. The room seemed so much bigger then. Now, I imagined the cohorts of hopeful kids who, like I had, came here to learn, their lives ahead of them, their dreams in their hands. They’d be anticipating the first day of school now. For many, that would mean end-of-holiday blues. But not for everyone. I remembered how desperately I’d longed for the gates to open again after the lonely stretch of the holidays. Had any of today’s students come from the same part of Bangladesh as us?

On my laptop, I was watching Linda on the school video. I’d met her at a number of community events, and found her warm and engaging.

‘At Mile End High School we’ve achieved something unique.’ Linda’s eyes shone with pride, and passion radiated in the muscles of her face. ‘Since the school opened in 1949, we’ve made it our mission to welcome all pupils from our continually changing community. We value all ethnicities and creeds equally, so you can be confident that your sons and daughters will learn and thrive in an atmosphere of wellbeing and safety.’

‘I suspect that’s going to come back to haunt her.’ The Australian accent yanked me back into the present.

I jumped. ‘Jeez . . . Do you always creep up on people?’ I paused the video.

Dan Maguire stood in front of me, holding out a packet of chewing gum. ‘Are you always this jumpy?’

Touché.

His pale skin and ginger hair were unusual. When he’d joked earlier about not fitting the bronzed Australian stereotype, he wasn’t wrong. Irish heritage, he’d said. Hated water and had a sunlight allergy.

I waved the gum away. Recalibrated. ‘Sorry. It’s this place. Weird being back here after all this time.’

‘I’ve been reading up on Haniya Patel. Doesn’t seem she felt safe either.’

I heaved in a breath. ‘No. Her death was a tragedy but nothing suspicious.’ I shivered and pulled my woolly scarf round my neck. ‘I don’t remember this place being so draughty. Don’t they have the heating on?’

Dan’s face was blank. ‘You think you’re cold? I went from summer in Australia to winter in the North of England. Back home my kids are swimming at Coogee Beach every day.’ He zipped up the neck of his jumper as if to support his point. ‘Dr Clark is downstairs at the crime scene with the CSIs if you’re ready to conduct a walk-through. And I’ve put the teacher, who found the body, in an office.’

‘Yup.’ I got up. Bundled my notebook and pen into my bag. Questions shot through my mind about Dan’s appointment but they’d have to wait. ‘I’m officially back off leave. I’ve told Briscall, who was delighted to hand over the SIO baton so, hopefully, we can get cracking.’

‘Good.’

I followed Dan across the canteen to the door, pushing down the awkwardness that was circling between us. A few minutes later, we were walking along the main corridor on the ground floor towards Linda Gibson’s office. My mobile rang. It was Alexej from the incident room.

‘Until we have a media liaison officer, put all press calls through to me,’ I replied. ‘The last thing we need is a sensational headline splashed on the front page. I’ll compile a holding statement.’ I rang off. ‘So much for sorting Suzie James out,’ I said to Dan. ‘She’s interviewing parents and the national news teams are on their way.’

‘It’s inevitable.’ He shrugged.

It was strange having a new team member. DS Barnes had been careering towards Professional Standards for years, but I’d got used to the way he and Alexej worked.

‘Right.’ I took a deep breath. ‘Let’s make a start on this crime scene.’

Outside Linda’s office, Dan and I reported to the guard, pulled on forensic clothing and followed the common approach path. It was a large room with floor to ceiling windows, and thick brown curtains pushed to the side. The first thing that hit me was the smell of vomit. Dotted round the room, crime scene investigators were quietly dusting for fingerprints, bagging up evidence, taking measurements, drawing plans and taking photographs. Objects had been knocked over. So, there’d been a struggle.

I headed over to Dougie McLean, the crime scene manager.

A grin darted across his features when he saw me. ‘I thought your flight only arrived back last night? You look shattered.’ He reached towards me, but he must’ve caught my frown as he retracted his arm quickly.

‘It did. You know me. Can’t see my old school in trouble, can I?’ I tucked my hair behind my ears and shifted into work mode. ‘What’ve we got?’

‘No sign of forced entry.’ He gestured to the windows. ‘The killer must’ve walked straight through the door.’

‘Prints?’

‘Lots. As you’d expect for a school. But a high cross-contamination risk. The guys have found some footprints and are still checking for blood and saliva. There’s a good chance of exchange materials, particularly fibres, hair and skin.’

‘Have we got a cause of death?’

‘Strangulation.’

I cast about. Objects were strewn round the room. The computer monitor, keyboard and telephone were in a tangle of cables on the floor, surrounded by several silver photograph frames. Soil, from a dislodged pot plant, was sprinkled over the cream carpet like brown sugar, and Linda’s office chair lay on its side several yards from the desk. It was as though someone had made an angry sweep of the desk surface or even hauled Linda’s petite frame over it.

Swarms of photographs adorned the walls: year groups, award ceremonies, openings, school plays, and sports days. Hundreds of lives in one room, all brought together by the school and Linda. What a terrible loss this woman was going to be.

Over by the corpse, the photographer was packing away his equipment.

‘Maya?’ Dr Clark, the pathologist, signalled for me to come over.

It was my first look at Linda’s body. Close up the rancid smell of vomit was more intense. A watery pool of it had collected at the bottom of her neck, with lumps of food speckling the white blouse on her chest. The perky face I’d seen on the video was barely recognisable; her delicate features had already swollen and her skin was blotchy. But it was her eyes that caught my attention, bulging from their sockets, bulbous and staring, the whites bloodshot. Beneath each socket, in a semi-circle, broken veins and congestion were forming dark channels. It was as though the killer had wanted to squeeze the life from her; to squeeze the eyes out of her head while they watched her suffer; to squeeze the last breath from her throat and lungs so she could never utter again.

‘Where’s the vomit come from?’ I was absorbing the scene in front of me.

‘Unless it was our killer, my guess is that whoever found her threw up over her.’ He moved closer to the body. ‘D’you see here?’ His gloved finger pointed at the reddish marks that were creeping through the surface of the skin on her neck. ‘I’ll be able to tell more after the post-mortem but these’ he pointed at fingernail gouges beneath her jaw ‘are probably defence wounds. The CSIs have taken nail scrapings. It’s likely the killer was squeezing her jugular vein and carotid artery, and crushing her windpipe, so she would have been gasping for breath immediately, and probably trying to pull their hands off her.’

Seeing Linda’s bloated face, with broken blood vessels and bruising spreading by the second, what struck me was that she would’ve known she was going to die. And that her last few moments of life weren’t going to be with her family but with someone who wanted her dead. She would have died while looking into the eyes of her killer.

‘You can see the swelling in her neck. Her tongue is engorged and has been bleeding where she’s bitten it.’ Dr Clark faced me. ‘There’s a good chance she scratched her killer’s face or pulled their hair. Even poked them in the eye.’

‘Any signs of sexual assault?’

He shook his head. ‘Not that I’ve seen. She has a small frame. Wouldn’t have taken much to overpower her.’ He moved closer to the body. ‘My guess is there was a struggle over by the desk, and she was killed on the floor or on the sofa, but Dougie’s team will know more.’

Had there been an argument and things had escalated? Or was this premeditated? One good thing was that strangulation involved high levels of contact: combined with the struggle, there was a good chance that fibres and hair from the murderer had transferred onto Linda.

On the cushion beneath her head, dark brown hair splayed, ruffled in places. Below her waist, her wrists rested at her solar plexus, bound together with a piece of white cloth. If the killer had simply wanted her dead, why had they tied her wrists?

‘Yes, the forearms are interesting.’ Dr Clark must’ve seen me looking. ‘She has numerous scars. See, here?’ He pointed to Linda’s wrists, which had been positioned so that the left one faced upwards and the right one crossed it. On the inside, at angles across the veins, cut marks had healed into white scars, some thinner than others, now almost blended into her pale skin. Others were jagged and thick, raised and pinker in tone.

‘The other one’s the same.’ He raised her hands gently so I could see. The right one had fewer scars, but they were more jagged. ‘I would imagine she was right-handed.’ Dr Clark placed her arms at rest.

I gulped. The cut marks upset me. Shocked me, even. They seemed unexpected in a head teacher. Or perhaps they were simply at odds with the smiling face I’d seen in the school video. ‘How old are those likely to be?’

‘Twenty years or so. No new ones. I’d put her as mid-to-late-forties. Extinguished while she was in her prime. Shame. She did well for this school. My brother-in-law is on the board of governors. It was heading for special measures when Mrs Gibson was appointed. He said she was a nice lady.’

As my eyes drifted back to the sofa, I noticed two evidence spots had been marked out. ‘What was here?’

‘I’ve checked the exhibits register.’ Dan came over. ‘One was a Chanel lipstick. The other was a piece of white card, with lettering on it. I’ve got a photo of it here.’ He passed me the image.

‘Some sort of ancient writing.’ I inspected it more closely. ‘And it was left by the body?’

‘Correct,’ said Dan. ‘Her handbag was knocked on the floor. The lipstick probably came from that.’

I studied the image. Passed it back. ‘Thanks. I want to know what it means. Can we get a translation ASAP?’

‘Sure.’

‘Before you head off, Doctor, anything else I need to know?’

Dr Clark took a final glance at the body and let out a long sigh. ‘Not really. It’s tragic. A scandal of this sort could send the school’s reputation plummeting.’

‘Not if I can help it. This place will be a source of stability for hundreds of kids.’ My attention travelled round the room. ‘And Linda clearly cared a lot about it.’

‘Ah, yes. I’d forgotten you’re a local.’ He chuckled. ‘Good to see you back. Dougie was worried you’d stay in Bangladesh.’ Dr Clark and I weren’t too far apart in age but his avuncular manner had become a habit we indulged.

I laughed. ‘Doubt that. Dougie knows better than anyone, if anywhere is home for me, it’s here.’ I changed tack. ‘When can you do the post-mortem?’

He checked his watch. ‘Unlikely I’ll get it done this afternoon. I’ve got two others to do tomorrow morning but I’ll bump yours up the queue. I’ll call you when I’ve finished.’

I returned my attention to Linda. On her back on the sofa, her petite frame and height made her resemble a young girl. Slender limbs and tiny hands created an impression of vulnerability that, in the flesh, was at odds with the vitality that exuded from the photographs and the school video.

‘Poor woman,’ I said to no-one in particular. Protectiveness had begun to stir in me. Who had crept into this woman’s office and strangled her while the staff were having lunch? What had Dr Clark said? Chopped off in her prime. The only way we could help her now was to find her killer, and try to soften the blow for her family and friends.

By Linda’s desk a CSI was documenting the photographs, which had been flung round the room. These were the first hint of Linda Gibson’s personal life. They showed her with a man, both swathed in hats, woolly scarves and padded mountaineering jackets, smiling together on a hill, arms round each other.

‘Presumably this is her husband?’ I turned to Dan. ‘How is he?’ It wasn’t just the greying hair. The man’s clothes and mottled skin tone suggested he was a good ten years older than Linda. Next to this was a close-up of the same man. Kindness emanated from his features. Soft, intelligent eyes and a warm demeanour.

‘Still in the Royal London Hospital. They’re monitoring his heart and blood pressure. He hasn’t taken the news well. Not long retired, apparently. Medical grounds.’

I took a closer look at the man in the photographs. Perhaps ill health accounted for him seeming older? It was hard to tell when Linda radiated so much energy and strength.

I was keen to get cracking with the investigation. Lines of enquiry were settling into place in my mind. The writing on the card was likely to be the killer’s signature, and it was a good place to start while the forensic data were being processed.

Beside me, Dan was swiping at his smartphone.

‘What d’you reckon that writing is?’

‘I can tell you.’ He enlarged the text and showed it to me. ‘It’s Pali. Part of a system of ethics. From a set of five ancient Buddhist precepts.’ His pale face was alight. ‘This one is the second precept and translates as: I shall abstain from taking the ungiven, whatever that means.’ He screwed up his face, clearly no wiser than me.

Buddhist precepts? Bound wrists and strangulation? It looked like this was a ritualised killing – and rituals always held enormous significance for the murderer. They also involved careful thought and planning.

What was Linda’s killer trying to tell us?

Wednesday

The precept says:

adinnadanna veramani sikkhapadam samadyani

I shall abstain from taking the ungiven

A Buddhist would say that where coercion is used, whatever is obtained hasn’t been freely given. That includes manipulation and exploitation. Instead, we are encouraged to do the opposite of taking: to give without any desire for thanks or benefit.

I know you believed that your role gave you the right to make decisions, but surely someone in your position should have exercised discernment? Shouldn’t you have put the needs of the vulnerable before your own selfish desires?

Mile End High School, 1989 – Maya

All summer I’ve been wondering how this moment would feel. With each step along the corridor the knot in my stomach tightens. Lockers line the walls ahead like a metal tunnel, so much bigger than the ones at primary. All the classroom doors are closed. Everyone else has arrived on time and they’ve started without me.

A tired ceiling light flickers. The corridor of scuffed linoleum yawns ahead. Today it’s the rush and hurry that I feel in the small of my back, pushing me on, but for a moment it reminds me of Heathrow airport, the day we arrived. Of being herded along endless tunnels with the others from our plane, in the wrong season’s clothes. Past faceless officials shouting things we couldn’t understand, as we left one world behind and were jostled into another.

Muffled voices bring me back to the present.

Giggles ricochet off the metal lockers and excitement bubbles up. New things to learn, new people. But anxiety soon dampens my eagerness: I knew my class at primary school but I’m not going to know anyone here.

Sabbir is a few steps ahead of me, his gangly legs striding forwards. He tugs the arm of my hand-me-down blazer with one hand, carrying my bag in the other.

‘Come on,’ he keeps urging. ‘You aren’t the only one that’s late.’

I’m glad my brother’s with me. Not Mum, whose spokesperson I always have to be. Or Jasmina, whose poise and beauty means I may as well be invisible.

‘Here we are,’ Sabbir announces finally when we arrive outside one of the closed doors. He checks the room number, peers in and hands me my bag. ‘I’ll meet you at the front entrance at 3.45 p.m. Okay?’

My guts crunch again, and I screw up my face to say don’t leave me, attempting to swallow down the panic that’s creeping into my chest. ‘How do I know what subject they’re doing?’ It’s a croak. My throat has dried out on the silent walk to school.

Taller than me, he ruffles my hair with his hand.

‘Don’t.’ I dodge out of reach, smoothing the everywhere hair that I’d brushed and brushed this morning to try and get under control.

The classroom door opens inwards, and suddenly a frowning face is in front of us, all lipstick and powdery skin. ‘Can I help you?’ The woman glances from Sabbir to me and looks me up and down.

She’s seen the pins in my skirt. The floor draws my gaze like a magnet.

‘Sorry she’s late,’ Sabbir mumbles. ‘Our mother isn’t . . .’ His voice dies out.

Inside the room I hear chatter swirl. And giddy, first-day-of-term laughter. The sounds are amplified like when we go to the public baths to have our showers.

‘And you are?’ The voice has an accent.

Sabbir nudges me and I raise my head.

She’s peering at me, as if she’s used to having her questions answered immediately.

And now I wish Jasmina was here and then the woman would look at my sister and not me, and ask her questions instead of me. I swallow hard. You’ve practised this. Come on. ‘Rahman.’ Then louder, ‘Maya Rahman.’

‘Oh yes.’ The frown’s still there beneath a thick fringe. ‘The Bangladeshi girl. I wasn’t sure whether to expect you.’ She steps back. ‘You’d better come in.’ She leads me into the classroom with a swish of her patterned skirt, and Sabbir fades away as I’m swept in front of a cascade of faces, and rows of tables, not like the individual desks at primary school.

Everyone freezes the moment they see me, halting their conversations and their carefree laughter to stare.

‘Now, year seven,’ the woman announces, with a chirpy lilt, ‘this is Maya Rarrrman.’ She presents me with a flourish of her hand, like I’m a stage act.

There I stand, weighed down by dread, swamped by my sister’s old uniform, with my raggedy hair and my funny surname. And the fear leans in: you aren’t the same as them.

On the giant pull-down board there’s writing. I can’t read it. It’s not English and it’s not Maths.

‘We’ve just started to introduce ourselves in French,’ the woman says, as if she read my mind. ‘Je suis Madame Bélanger. Bonjour May-a.’ Her pasted smile does little to reassure me, and all I can think about is that everyone’s still staring at me and I can’t take in a word she’s saying and I haven’t a clue what she said her name is.

The room smells like stale crisps. I’m searching for a free seat.

‘Do you want to sit on the end there, next to Fatima?’ The teacher points to a grey table, wagging her finger. ‘Fatima, bougez-vous, s’il vous plaît? Voilà. You can have my chair.’ She picks up her seat, sets it down next to the wall and pats the back rest. ‘You can be friends, you two, n’est-ce pas?’

I take my bag over and perch.

‘Alors, on continue,’ the woman says as she glides back to her desk and surveys the class.

All the sounds merge together now. My senses swim and I eye the door. I can make it if I run. Throat tight, my eyes fill up. I blink and blink, determined not to dab them, and wipe my nose rather than sniff conspicuously. All the time I’m thinking, it wasn’t meant to be like this.

And I’m wondering whether I would feel different if Mum or Dad had come with me.

Wednesday – Dan

As soon as Dan entered Roger Allen’s scruffy office, two things struck him: Allen was out of favour, and was at the bottom of the management pecking order. Scuffed walls were crying out for a lick of paint, and two of the ceiling lights were on the blink. It gave a very different impression from the showroom of Linda Gibson’s office and the swish reception area.

Steve Rowe cut a dejected figure in a chair behind the desk. Trackie top. A face full of stubble. Mid-to-late twenties. A rookie.

Maya took the lead. ‘Mr Rowe? I’m DI Rahman and this is DS Maguire.’