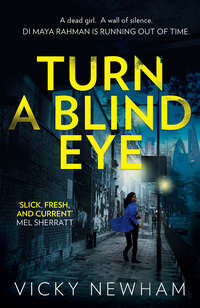

Turn a Blind Eye: A gripping and tense crime thriller with a brand new detective for 2018

Steve closed the flat door behind him. The place was hardly any warmer than outside. Never mind. He’d soon be under the covers. Then his gaze fell on his sister’s gym bag in the hall. ‘

‘Ah, bollocks.’ He’d left his messenger bag in the Morgan Arms. He’d get it tomorrow. He couldn’t face trekking back there now. Carrying a pint of water, he headed straight for the spare room at the end of the landing. This was home for the next few months until he could find a place of his own.

He took his mobile out of his jeans, rang the pub and asked them to hold on to his bag. Then he sat on the edge of the bed. On the floor his rucksack leaned against the wall and his attention fell to the key ring that Lucy had given him, with the letters NYC, when she’d first told him she wanted to return home to the USA.

He felt a dart of pain in his stomach. How long was it going to take until he could think about Lucy, and see things that reminded him of her, and not feel regret?

Just get into bed, you idiot. And stop feeling sorry for yourself. You’ve only got yourself to blame. Lucy gave you fair warning. Claiming indignation about her going home to the States was never going to cut it, and nursing your pride isn’t going to reverse things.

He exhaled, swung his legs up and lay back on the mattress. Within minutes of head and pillow meeting, Steve’s breathing slowed and he was snoring. Until –

‘Hey. Sleeping Beauty.’

The overhead light flicked on.

‘Wake up.’

Steve’s eyes were dazzled. The abrupt waking jolted him from his boozy sleep.

It was Jane in strident mode, standing over the bed with hands on hips. ‘It smells like a pub in here. How much have you had?’

‘Oh fuck,’ he groaned and pulled the pillow over his face. Dread surged through him along with ripples of nausea. Jane on a rant was bad enough when he was on top form.

‘From what I’ve heard, you already did that. D’you want to explain why I’ve had a call from Lucy first thing this morning, and then one from some DI Rahman woman about your school?’

‘Not really, no.’ He might have guessed Lucy would be on the phone to Jane. They’d been close for several years. ‘Look, do one, will you? My head hurts. I’m not up to one of your inquisitions.’ He replaced the pillow over his eyes.

She yanked the duvet off the bed and onto the floor, leaving Steve naked, except for his boxers and the pillow over his head.

‘Piss off. Don’t do that.’ He lobbed the pillow to one side, reached over to grab hold of the pastel pink duvet cover and pulled it back over him. This was something his sister used to do when they were growing up and it had always infuriated him. As she clearly remembered.

‘Well?’

Steve didn’t answer. He rolled over and tucked the pink duvet under his chin in case she tried to pull it off again, feeling like he was about six.

‘You heard me. What’s going on?’

‘I’m not talking to you when you’re in this mood. The last forty-eight hours have been a pile of crap. Now can you please leave me alone?’

‘The detective wanted me to confirm you’re staying here.’

‘I am, aren’t I?’

‘She said you’ve been involved in a serious incident. What’s happened?’

‘We aren’t allowed to talk about it.’

‘Bit late for that. It’s already on the national news. The head teacher of your new school’s been found dead.’

‘If you know what’s happened, why are you asking?’

‘Oh my God, was it you who found her?’

‘Yeah. Now please leave me alone.’

‘So, you aren’t interested in Lucy’s message then?’

‘What message?’ Curiosity replaced the world-weary, about-to-die tone in his voice. He was facing her now.

‘If you’re showered and dressed and in the kitchen in ten minutes, I’ll tell you.’

Brick Lane, 1990 – Maya

‘In here, you two,’ Mum calls from the kitchen.

Plunged into darkness, Jasmina and I grope our way out of the lounge to join Mum. Illuminated by the blue light of the gas ring, she’s at the stove. Sweet, spicy smells waft round the kitchen, and there’s a pot bubbling on the hob.

Outside, even the street lamps have gone off and the whole terrace is in darkness.

‘I wonder how long this one will last,’ I ask.

Mum has placed a candle on the table. She strikes a match and it fizzes. Smells. The wick catches, casting a ball of light momentarily before shrinking.

‘Sit here.’ She’s pointing to the table. ‘And for goodness sake mind your hair on the flame this time, Maya.’

Jaz and I cram round the tiny Formica table where the five of us sit every evening for tea, knees banging, feet jostling for space against Dad’s work boots and Sabbir’s huge school shoes.

Jasmina and I sit now, side by side on the wooden bench, and the soft light of the candle flickers, casting a spell over the room. Shadows sway around the dingy, smoke-yellowed walls. As the wick waves in the draught, the flame billows and casts looming shapes. Homework forgotten in the excitement, Jaz tickles me and I poke her; we giggle and wriggle in the tiny kitchen.

‘Stop it.’ Anxiety rattles in Mum’s voice. She always gets tense when the electric goes off. And when Dad’s late home. ‘When your father gets in, he can get some more candles. Jasmina, call upstairs to your brother, will you?’

In the chilly air of the flat, steam trails upwards from the saucepan as Mum stirs it. The walls round the cooker shine with condensation.

A few minutes later Sabbir arrives, with bed-head hair and sleep furrows in his bruised cheek. ‘What’s for tea?’ He glances round the kitchen.

We all know the answer, but each day we hope it might be different. We love Mum’s cooking, but after eight years of school dinners, and tea sometimes at friends’ houses, we’ve got used to eating different food. Perhaps Dad will come home with a treat for us all? A bagel each from the shop in Brick Lane, or some red jam to have on sliced bread?

‘Rice and curry,’ Mum says. She always talks to us in Sylheti, and at home my sister and I speak our mother tongue too. Unless, of course, it’s something we don’t want Mum to hear.

‘It’s the second power cut this week, isn’t it?’ Sabbir is the eldest of the three of us.

Mum serves out the stodgy rice and curry, and passes bowls over one by one. ‘Careful. They’re hot.’ All seated round the table now, Dad’s chair sits empty, no bowl on his place mat, just cutlery and an empty water glass. ‘We may as well eat. Your father’s obviously got held up again.’ The words ride a sigh.

My socked feet are cold. I like it when I can rest them on Dad’s work boots. Get them off the cold concrete and warm them up.

Just as we’re finishing our tea, we hear the front door bang shut downstairs, and a few moments later the grinding sound of a key in the flat door. Dad comes in, bringing a whoosh of bitter winter air and cigarette smoke, and another smell I’ve noticed before. The draught pulls the candle wick first one way then the other, and Mum jumps up to shield Sabbir from the billowing flame, bashing the table and knocking over her water glass. She uses a tea towel to mop first the water then the gash of wax that’s run onto the shiny tablecloth.

‘While we’ve been here with no power, you’ve been in that pub again. I can smell it.’ The reproach is unmistakeable. ‘This is the last candle. We need more. The children can’t sit in the dark.’

Dad looks at Mum, and then shines his gaze like a torchlight round the table. Pauses.

I’m watching him. Wondering what he’s thinking and what’s going to happen. I grab Jasmina’s hand under the table. He looks over at the hob, then back to the table. The room shimmers with tension and it makes my skin prickle. Every day now, Dad’s late and Mum says the same thing. He must be tired and hungry after working all day, but it’s as though there’s more to him going to the pub than either of them mentions.

Dad lets out a long sigh, like letting air from a balloon while holding on to its neck. In the soft light, his cheek muscles quiver. ‘I’ll go and get some now.’ He and Mum whisper to each other in very fast Sylheti.

My breathing tightens.

As he turns, I get another waft of that smell, the one his clothes so often reek of. ‘Won’t be long,’ he says in English.

I feel a swirl of something in my stomach, pulling at me. I put down my spoon. I don’t want Dad to go out again. He’s home now and it’s cold. I look into his face, with its gentle creases, the dark growth round his face, and his large eyes the colour of conkers.

‘Dad?’ I can’t help saying. I don’t know why.

‘You children be good for your mother,’ he says sternly, and ruffles my hair with his hand. When he stops, he lays his palm flat on the top of my head for a second, and I feel momentarily held in his warmth before he removes it. He gabbles something else to Mum in Sylheti, his voice even lower than usual. A jumble of sounds, noises, tones.

I squeeze Jaz’s thumb. Use my eyes to plead with her, but she shrugs and shakes her head.

Before I know it Dad pulls the flat door behind him and the latch clicks shut. He never even took off his coat and now he’s gone.

Mum’s spoon drops from her hand and clatters on the bowl in front of her. She closes her eyes, sucks in a long breath and lets it out, at first with a low moan, like an animal in pain, then in a full-throated wail.

‘Mum?’ She’s never made a noise like this before. ‘Are you okay?’

Sabbir’s chair screeches on the hard kitchen floor as he pushes it back to stand up. ‘Okay. Let’s all play a game.’

I know something’s happened, but have no idea what. ‘Dad will be back soon with the candles, won’t he? We can finish our homework then. I’ve got English to do and Jaz —’

‘We can play ’til then.’ Sabbir looks over at Mum, and I follow his gaze.

She’s sniffing, dabbing her nose and fanning herself with her hand. ‘I’m fine,’ she says, her voice faltering. ‘Just give me a minute.’

But I can still hear that moan in my ears and I know we can’t leave her.

‘How about we get the blankets from our bedrooms and put them on the floor in here?’ It’s Jasmina. ‘If we push the table over, we can make a camp. Mum?’

Excitement bubbles up. I love camps. ‘We could sleep down here too.’

‘We may have to if the power doesn’t come back on soon,’ says Mum.

Five minutes later, Jaz, Sabbir and I have fetched our bedding from upstairs. Mum has cleared away the dishes and pushed the table against the wall. On the gas hob a pan is heating for our hot water bottles. We pile cushions onto the eiderdowns and clamber on top. Our bottles filled, Mum joins us, but with her back against the wall and her legs under the covers.

‘Tell us about Bangladesh again,’ I ask Mum. ‘What was it like growing up outside the city?’ All three of us love to hear her stories. We’d lived in the city centre of Sylhet so this part of our home country wasn’t something we knew well.

Mum speaks slowly as though she’s combing through her memories and putting them in place. Hearing her speak in Sylheti feels completely natural. Comforting, somehow. It’s like being in our old flat by the river.

‘One of my favourite things was the rolling hills. The land often flooded, especially in the monsoons, and lakes formed on the flood plains. Sometimes your grandfather took us into the swamp forests by boat. They’re magical places where trees grow out of the water. Their branches join up at the top to form canopies and tunnels.’ Mum gestures with her hands.

In the soft candlelight I catch the look on her face, as though the memories bat her back and forth between pleasure and pain.

‘Living here in London, in the cold and grey and the dark, I miss life by the river and the lush green colour. After the monsoons, beautiful star-shaped pink water lilies would float on the lakes. Sabbir, d’you remember the migratory birds? You always loved the swamp hens, didn’t you?’ Her melancholy makes me wonder how she feels about us moving to Britain. ‘The tea estates are glorious,’ she says, making a sloping gesture with her arms. ‘Carpets of green bushes, all trimmed to waist height. My mother and her sisters would pick the tea. I went once to help.’ The soft candlelight melts the ache in her features. It warms her voice for the first time this evening. ‘My father’s family grew rice.’ Energy builds in her voice. ‘I liked to watch the buffalos treading on the rice hay to dislodge the grains. It’s the traditional way of doing it. Afterwards we’d all swim in the Surma, and watch the cattle as they drank in the river. They’re —’

The flat buzzer silences her, and we all jump. Wrenched from the vivid colours of Bangladesh back to our dark kitchen.

‘Who’s that, ringing at this time?’ Mum’s tense again.

‘Perhaps Dad’s forgotten his key?’ It’s all I can think of. ‘I’ll go.’ I get up and feel my way to the hall, my eyes used to the dark. I open the door, expecting Dad to rush in, laden with bags, full of apologies and jokes and stories.

But there’s no-one there.

‘Who is it, Maya?’ Mum shouts through.

‘No-one. Someone must’ve pressed the wrong bell.’ I step outside the flat into the hall and, smelling tobacco, I scour the darkness for a glowing cigarette end or the light of a torch. My foot knocks against an object on the ground. There’s something beside the doorway. I lean over to feel what it is. A plastic bag rustles in my fingers. In it is something hard, like a cardboard box. I pick up the package and carry it into the flat.

‘Someone left a parcel.’ I place it on one of the kitchen worktops.

‘At the door?’ That tone is back in Mum’s voice. ‘For pity’s sake, Maya —’

‘No-one was there, just this bag.’ I point, although it’s obvious.

‘Give it to me,’ says Mum sternly, moving towards the worktop.

But Sabbir has already begun rummaging in it. He looks at us all in turn, his face excited. ‘It’s candles and . . . you’re never going to guess what . . .’

‘Bagels?’ Jasmina and I shout in unison.

Wednesday – Maya

When I got home and closed the front door, relief surged through me. It wasn’t my brother’s photo in the hall that brought the tears, nor the suitcase I’d parked by the stairs when I arrived home in the early hours. It was that, all day, my attention and energy had been on the investigation when what I wanted was to be alone with my grief. Now, I finally had the chance to gather it up so I could feel close to Sabbir; to wade through all the conflicting emotions about how he’d died – and why.

In the kitchen, I lobbed my keys onto the worktop, followed by the soggy bag of chips I’d half-heartedly collected on the way home. In the cold air, the smell of malt vinegar wafted round the room and the greasy mass was unappealing. I flicked on the heating. Next to the kettle, the message light was flashing on the answerphone. Mum had probably forgotten I’d gone to Bangladesh for the funeral.

Through the patio doors, the light was reflecting on the canal water in the dark. When I was house-hunting, I’d had my heart set on this flat as it reminded me of Sylhet and our apartment there when we were growing up. I remembered how sometimes, when he’d been in a good mood, Dad would sit between Jasmina and me on our balcony there and read us the poems of Nazrul Islam. On those rare occasions, the two of us would lap up the crumbs of Dad’s attention, bask in his gentle optimism, oblivious to the stench of booze and tobacco on his breath, and the smell of women on his clothes and skin.

What I remembered most, though, was how yellow his fingertips were; the feel of his cracked, dry skin. And how much I’d loved his burnt-caramel voice.

I headed into the lounge. Last night’s array of mementos littered the coffee table, waiting to be stuck into the journal I’d bought from the market in Sylhet. The fire had destroyed most of Sabbir’s belongings so Jasmina and I had chosen what we wanted from the bits that were recovered. My eyes fell on the book of Michael Ondaatje poetry. He’d annotated it. On the plane home, I’d read every single poem and pored over all my brother’s notes, then wept in the darkness of the cabin. I’d learned more about Sabbir from those poems than all our conversations.

Sometimes the canal outside was soothing. Tonight, although the water was still, I felt it pressing in on me. Unable to shift Linda’s death from my mind, I kneeled in front of the wood burner. As I lay kindling on the bed of ash, my thoughts drifted back to the amalgam of conversations from earlier in the day. I was exhausted. A combination of jet lag, lack of sleep and not eating. I was contemplating having a bath when my mobile rang. It was Dougie.

‘Hey, how are you?’ We’d Skyped several times when I was in Bangladesh but, other than seeing him at the crime scene, I hadn’t had the chance to catch up with him since getting back. He was downstairs, so I buzzed him in and went to meet him at the door, pausing briefly to check my appearance in the mirror.

‘I was on my way home. Wanted to check you’re okay.’ He leaned over and his beard growth brushed my cheek as he gave me a kiss.

I drank in the smell I knew so well, and, for a moment, I longed to sink into his arms. ‘Shattered, but pleased to see you. Come in.’ I began walking away from the door. ‘I was going to call you.’

He followed me along the hall and into the kitchen. Pulled the overcoat off his large frame and draped it over a chair back.

‘Fancy a beer?’ I said.

‘If you’re having one.’

I took two bottles from the fridge and passed him one.

‘You’ve met the fast-track sergeant, then.’ He took a swig of beer.

‘Yeah.’ I sighed, irritated. ‘Briscall must’ve known about this for a while. Nice of him to mention it.’

Dougie’s bushy eyebrows shot up. ‘That man’s a prick.’ He strode over to the window and back. ‘Gather this Maguire bloke’s an Aussie? What’s he like? Have to say, he looks more Scottish than I do.’

‘He seems a good cop. Knows his stuff and he’s pretty sharp in the interview room. Briscall will never change. I had a lot of time to think when I was in Sylhet and I’m done with letting him wind me up. I joined the police to make a difference, and to help people like Sabbir. I’m fed up with Briscall side-tracking me with his petty crap.’

Dougie had one hand round his beer, the other in his pocket. He was taking in what I was saying. ‘How’s it going with the school and the Gibsons? It’s all over the media.’

‘No real leads. We’re waiting to interview two key witnesses. One’s under medical supervision, the other’s gone AWOL.’ I groaned with frustration. ‘We’re still puzzling over the Buddhist precepts. There are five of them. Why the killer has started with the second, we don’t know.’ The cold had reached my bones today and I needed to warm up. ‘Shall we go through? The stove’s on.’

In the lounge, Dougie sank into the sofa, his manner quiet and reflective.

‘As a murder method, what d’you reckon strangulation says about the killer?’

‘I’m not sure.’ He paused to think. ‘It’s quick and doesn’t require any weapons. Silent apart from victim protests. Excruciating agony for a few seconds, depending on the pressure, then the victim slips into unconsciousness. Death minutes after that. It’s certainly different from stabbings and shootings.’

I was nodding. ‘On training courses we’re continually told that murder methods are rarely random or coincidence, except in the heat of the moment. Whoever murdered Linda chose to strangle her, bind her wrists and leave a message by her body.’

Dougie was stroking his chin. Silent for a few moments. ‘It’s certainly symbolic. Whoever did it could’ve simply strangled her and left.’

The material that had been used to bind Linda’s wrists wasn’t expensive, but Dougie was right: for the killer to bother, it must symbolise something for them. And forethought had gone into what they had chosen to write. It wasn’t an impassioned scrawling of ‘BITCH’ across a mirror in red lipstick, for example.

‘The most logical explanation is that the two acts go together.’ I held my forearms the way Linda’s had been positioned. ‘The precept says, I abstain from taking the ungiven. If your wrists are tied, so are your hands.’

‘Bingo. You can work from there. Although, hang on.’ Dougie placed his beer on the coffee table. ‘Did you say there are five precepts? Do you think the killer’s started with the second precept because of its significance? Or do you suppose there’s been a murder before this one?’

Wednesday – Dan

The Skype ring tone danced around the small bedroom. ‘Pick up, pick up,’ Dan urged, as he pictured the early morning scene at home in Sydney: Aroona getting the girls ready for whichever club or friend they were going to today. It was nearly midnight and Dan was wide awake in his Stepney flat-share. Every cell in his body felt as though night-time had been and gone. He lay beneath his crumpled coat, shivering, longing for the unbearable heat of home.

On his phone the pixelated image solidified. ‘Daddee,’ came Kiara’s squeal through the ether, and the video clicked in. She had a huge grin on chubby cheeks, her face still full of sleep.

‘Hey, kiddo. How are you?’ Dan searched her features for tiny signs of change, drinking up their familiarity. ‘I really miss you guys.’

‘Is it cold there? Mum said you’ve got, like, minus twenty or something.’

Dan chuckled. Swallowed the lump in his throat. Her innocent exaggeration was refreshing. ‘Not quite. It is cold, though, and we’ve had a bit of snow.’ It was so good to hear her voice. ‘Did you go to the beach yesterday?’

Another face bombed the picture. Sharna. All soft curls and gappy teeth. ‘Snow? Take some photos.’ A gaping mouth loomed in, and she attempted to point at her gums. ‘The toof fairy came last night, Daddy.’

‘Is that right? What’d she bring?’

‘A new toofbrush.’

Both girls dissolved into giggles. It was a typical Aroona present.

Homesickness pinched at Dan. Being apart from his family and missing out on milk teeth and swimming lessons . . . He hoped they’d all be able to join him soon.

‘Mum’s coming,’ said Kiara. ‘I got burned today. I’m all scratchy.’ She rubbed at her neck and face as though needing to make her point.

He’d only been away four months. Living in Sydney, he was used to hearing an eclectic mix of accents, but the combination was different in East London. The familiar Aussie vernacular was comforting but sounded different from the way it normally did. More distinct.

Feet shuffled across the laminate of their apartment. Aroona peered over the top of the girls’ heads, her dark hair a contrast with Sharna’s blonde and Kiara’s red.

‘Hey,’ Aroona said. ‘How come you’re still up?’ She was holding a giant tub of mango yoghurt with a spoon in it, and in the background the TV was blaring out the weather in New South Wales.

‘Oh, you know. Wanted to speak to my girls.’ Around him, magnolia walls were devoid of home touches. On the floor beside his bed, the greasy KFC box reminded him how hungry he was. He brought his wife up to date with Maya’s return. ‘I’m still trying to find a proper apartment.’ He wanted to ask if she’d thought further on when she and the girls would join him, but didn’t want to upset the geniality of their conversation. Things were shifting for the Aboriginal communities and he knew how much Aroona cared about helping them. ‘I’ve heard about the tooth fairy. How did the swimming lessons go?’

In front of him the girls squirmed and giggled.

‘She did very well and —

Her reply was drowned out by a banging on the flimsy party wall of Dan’s room. ‘Trying to sleep here, mate!’ boomed the voice of the flatmate he’d heard but never met.

‘I’d better go,’ Dan hurried, irritation bubbling in his throat. ‘It’s late here. Speak soon, Okay?’