Loose Cannon

Things would change soon, though, Hasem reasoned. Even as he was exhorting the recruits, the charismatic leader knew that JI teams in Banda Aceh were preparing to launch what would be the first in a series of counterstrikes against Densus 88. If all went well, when the dust settled, JI’s reputation would be such that once again they would be able to pick and choose from the swelling ranks of those eager to join the cause. For now, however, Hasem would make do with what he had.

Hasem lectured his minions a few minutes longer, giving the men a well-practiced spiel heavy on references to Allah and laden with vitriol demonizing the United States as the Great Satan. Much was made, too, of the threat posed by secular leaders throughout the islands—men like Governor Zailik of Aceh Province—who took a hardline stance against Islamic fundamentalists. Those local politicians, to Hasem’s way of thinking, were every bit a hindrance to what JI stood for as the Americans and their European counterparts. Indonesia, after all, contained the highest Muslim concentration in the world. What better place for Islam to flourish and lay the groundwork for a long-overdue return to global prominence?

A breeze rustled through the camp, and as the recruits detected the smell of fried rice and roast goat coming from the kitchens set up inside the former treatment plant, Hasem could see the men’s attention beginning to waver. He quickly wrapped up his remarks, then sent the men to eat.

A truck had pulled up to the site, parking near Hasem’s quarters, a rusting Quonset hut set back at the edge of the clearing. Hasem went to check on things, catching up with the driver as he was circling around the truck.

“Did you get it?” he asked.

“See for yourself,” the driver told him. He opened the rear doors of the truck, revealing an oblong wooden crate the size of a small coffin. The lid was unfastened, and when Hasem raised it, he smiled. Laid out in neat rows within the crate where thin slabs of Semtec. Once placed in the lining of snug vests worn beneath loose clothing, the plastic explosives would be difficult to detect to the visible eye. As such, they would be a far better choice for suicide missions than dynamite sticks or the other, bulkier explosive materials JI had been forced to rely on, thanks to Densus 88’s clampdown on the black market.

“Excellent,” Hasem said, placing the lid back on the crate. He told the driver to wait while he went for his payment, then headed toward the nearby hut. He was met in the doorway by one of his lieutenants, Guikin Daeng, a sallow, sneering man in his late twenties.

“I was just coming to track you down,” Daeng told Hasem. “We just received word from our team in Banda Aceh. Governor Zailik is setting out early for the airport, just as we hoped.”

“Our little demonstration scared him out of his cozy little nest?” Hasem asked.

Daeng nodded, then squawked like a chicken and laughed.

“Out of the frying pan,” Hasem intoned. “Into the fire…”

3

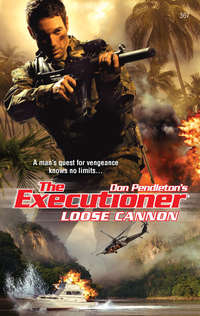

Nearly twenty-one hours after its departure from a private airfield in Washington D.C., the Cessna Citation X jet carrying Mack Bolan dropped through the cloud cover veiling the Strait of Malacca, giving the Executioner a glimpse of Banda Aceh. He was seated in the lavishly appointed eight-seat passenger cabin, his view out the right window only partially obstructed by the jet’s sub-mounted wing. The jet was RICCO booty recently claimed by the government after the arrest and conviction of a high-rolling Chicago drug dealer.

The Executioner wasn’t the only passenger aboard the jet.

“Y’know, I could get used to this,” John “Cowboy” Kissinger drawled from the seat next to Bolan. Legs stretched out, the Stony Man weaponsmith had his feet propped on a foldout table that also held the remains of a gourmet breakfast he’d put together in the jet’s galley after sleeping most of the trip with his leather-and-suede chair fully reclined. “Only thing missing was some foxy stewardess ready to initiate me into the Mile-High Club.”

“Maybe next time,” Bolan deadpanned.

Some years back, Kissinger had left his career as a DEA field agent to join the covert ops team at Stony Man Farm. The original plan had been for him to stay on-site and oversee the acquisition and maintenance of the vast arsenal stockpiled in an outbuilding near the main quarters, and he’d excelled at both functions while finding time to tinker with new prototypes and modify existing weapons to improve performance and reliability in the battlefield. In time, though, he’d come to miss taking on the enemy firsthand, and whenever Hal Brognola or Barbara Price found themselves shorthanded when doling out assignments, Kissinger was usually the first to volunteer. Conversely, whenever Bolan felt the need for backup going into a mission, he invariably turned to Cowboy, as well as the pilot currently minding the Citation’s controls.

“Okay, boys and girls,” Jack Grimaldi called out over the intercom as the jet continued its descent toward the airport located six miles inland from Banda Aceh. “You know the drill. Seats up, belts on, and stash away anything you don’t want pinballing around the compartment should I suddenly forget what the hell I’m doing and wind up dribbling this sucker across the landing strip.”

Kissinger got up long enough to take his and Bolan’s breakfast trays back to the galley, then strapped himself in for landing. He saw the Executioner still staring out the portal beside him.

“Already looking for that needle in the haystack, eh?”

“Something like that,” Bolan replied.

In truth, though, the Executioner’s attention was focused on a flurry of activity around one of the far hangars, where a handful of armed men in combat fatigues were crossing the tarmac toward where crews were hastily fuelling what looked to be a vintage Vietnam-era Huey. A pair of military Jeeps had pulled up alongside the combat chopper as well, ready to take on a few more passengers. Kissinger finally glanced out the window and caught a glimpse of the pandemonium.

“That’s our hangar, isn’t it?” he asked Bolan.

Bolan nodded as he continued to monitor the activity. “I have a feeling they’re up to something besides rolling out the red carpet….”

“NICE TIMING, MATE,” Shelby Ferstera told Bolan ten minutes later as the Executioner deplaned. “You want to hit the ground running, you’ve come to the right place.”

Ferstera was a tall, broad-shouldered Australian in his early forties. A former member of that country’s elite Special Forces, Ferstera now served as field commander for Densus 88, eighty-eight being the number of Australians killed during the deadly 2002 bombings in downtown Bali. Ferstera had lost a sister in that bloodbath, so he’d been among the first to volunteer for the counterterrorist unit, joining forces with several U.S. Delta Force veterans and a handful of CIA operatives, who, with the help of well-trained Indonesian nationals, had been instrumental in thwarting Jemaah Islamiyah’s efforts to surpass the carnage wreaked in the Balinese incident. Their tactics over the years had been as effective as they had been controversial, resulting in the arrest of several thousand JI conspirators and the deaths of several hundred others.

Still, Ferstera knew the enemy was far from defeated, and he was not the sort of man to let pride get in the way of welcoming another ally in the fight. He’d been given the standard cover story that Bolan, under the alias of Matt Cooper, and his crew were special agents for the Justice Department, but the Aussie knew better. When told by his CIA colleagues not to pry into Cooper’s background, Ferstera felt certain that by sending these men to help with the situation in the islands, the U.S. had decided to play an ace stashed up its sleeve.

For his part, Bolan at first misinterpreted the commando’s greeting.

“You found Ryan?” the Executioner asked as he shook the Australian’s hand.

“We’ll give you a hand with that in good time,” Ferstera assured Bolan. “Meantime, how about a little warm-up exercise?”

Bolan stared past Ferstera at the Huey and the waiting Jeeps. If Ryan had not yet shown up on their radar, he knew enough about Densus 88 to know who they were preparing to go after. “JI?”

Ferstera nodded. “We’ve got an informant who says they staged a rally in town so they could flush the governor from his quarters. He’s on his way here, and he left without a full security clearance. Worse yet, he’s taking the back way to avoid traffic. My money says he’s heading for trouble.”

The situation seemed far afield from Bolan’s intended mission, but he wasn’t about to back away from Ferstera’s request. Once Grimaldi and Kissinger caught up with him, he quickly relayed the news, then turned back to Ferstera and asked, “Where do you want us?”

DUE TO THE LAST-MINUTE change in the governor’s itinerary, only two of the intended six motorcycle patrol officers were available to escort Noordin Zailik when he prepared to leave his government quarters in a chauffeured Lincoln Town Car. The police helicopter scheduled to provide aerial support at the original departure time was en route from an assignment in nearby Lheue. It was expected to catch up with the governor by the time he reached the back country road serving as his alternate route to the airport. In the meantime, the down-sized motorcade took a circuitous route through the city, taking care to avoid Baiturrahman Grand Mosque as well as main thoroughfares or any other area where protestors were likely to be gathered.

Zailik was too preoccupied with other matters to give much thought to his compromised security. He’d been on the phone since the moment he’d sat down in the car, and now, miles later, as he closed his cell phone after speaking with Provincial Intelligence Director Sinso Dujara, Zailik frowned to himself. Something about Dujara’s demeanor during the call had seemed off. Dujara was, by nature, both contentious and territorial, and Zailik had expected the man to bristle at the suggestion that not enough was being done to ferret out clues regarding the deadly incidents in Gunung Leuser. Instead of being defensive, however, Dujara had gone so far as to apologize for the lack of progress in the investigation and welcomed Zailik’s suggestion to allot more manpower to the task. An apology? A gesture of humility from the most arrogant man in his makeshift cabinet? It just wasn’t like Dujara. Something wasn’t right.

Or maybe I’m just being paranoid, Zailik thought.

He tried to put the matter out of his mind as he fished through his coat pocket, taking out the notes he’d been working on for his upcoming fund-raiser speech in Takengon. He was glad that he’d decided not to cancel the appearance, which he knew could have a strong bearing on the final stretch of the governor’s race.

Takengon, located in the center of the province on the shores of Laut Tawar Lake, had long had aspirations of becoming a tourist mecca, but most travel guides still balked at recommending the area based on years of bloody skirmishes in the vicinity, most of them involving GAM separatists. In truth, there had been no political violence in the area since the tsunami. But the stigma remained, and as such Takengon’s movers and shakers were adamantly opposed to the gubernatorial candidacy of Anhi Hasbrok, who’d commandeered GAM forces in most of the battles waged near the aspiring resort. And since third-party candidate Islamic cleric Nyak Lamm had denounced leisure pursuits such as water-skiing and sunbathing as degenerate Western vices, Zailik was certain he’d be able to replenish his campaign coffers by assuring the locals that he remained a steadfast champion of tourism as well as a foe of clerical involvement in regional politics.

The governor quickly lost himself in his speechwriting, and it wasn’t until his chauffeur cursed under his breath that Zailik took his mind off the task long enough to glimpse out the window. In an instant, he realized it may have been a mistake to take the back way to the airport.

The motorcade was passing along a remote, two-lane stretch of roadway that separated a partially completed low-income housing development from a rolling meadow overrun by tents and clapboard shanties where thousands of displaced residents of Banda Aceh had been living in squalor and discontent as they waited for construction on the new homes to be completed. The development was two years behind schedule, thanks largely to the former U.S. ambassador’s pilfering of tsunami relief funds. However, many of the indigents held Zailik responsible for their dire straits, and it seemed someone had leaked word that he would be passing through the area. Several dozen people had wandered out from the tenement and taken up positions along the road, where they jeered and waved their arms angrily at the approaching motorcade. The crowd was made up primarily of men, though there were a handful of women and several boys in their early teens. As the car drew closer, they collectively drifted out onto the road, forming a human barricade.

“So much for avoiding demonstrators,” Zailik mused as he eyed the throng. The chauffeur slowed the car and the patrolman who’d been riding behind them pulled around to the front, joining his counterpart. They stopped their motorcycles at an angle, forming a protective V behind which the governor’s car eased to a halt twenty yards shy of the protestors. Beyond the demonstrators, Zailik saw two cars approaching from the direction of the airport. Apparently dissuaded by the commotion, both drivers slowed and made quick U-turns, leaving the confrontation behind.

Zailik fumed. He wanted to get out and confront his detractors. What business did they have making him a scapegoat for their miseries? The tsunami hadn’t been his fault, and when Ambassador Ryan’s wholesale embezzlement had come to light, it had been Zailik who’d spearheaded efforts to secure relief funding elsewhere. If not for him, the lot across the road would still be nothing more than a pad of dirt instead of a development where there were at least signs of forward progress.

The governor’s indignation was quickly tempered when a piece of rotten fruit splattered against the tinted windshield he was looking through. Zailik instinctively recoiled, then let out a gasp when the next projectile—a rock the size of a baseball—struck the window. The glass was bulletproof and the rock left only small, weblike cracks, but Zailik suddenly realized he was facing more than a mere inconvenience. Casting aside his speech notes, the governor quickly grabbed his cell phone. Too flustered to dial a number, he instead pressed Redial, putting a call through to Intelligence Director Dujara. The official had little to do with the governor’s security arrangements, but Zailik was desperate.

“There’s a mob on the road to the airport!” he bellowed once Dujara picked up. “They’re after me…!”

4

The two motorcycle officers were brothers. Muhtar Yeilam, the oldest by three years, had joined the Banda Aceh police force straight out of college and distinguished himself as a patrol officer during the tsunami, saving a handful of lives and helping to maintain order in the storm’s traumatic aftermath. Muhtar’s example—along with the ceremony where he’d been decorated for heroism—had inspired his younger brother to follow in his footsteps. In three months Ashar would have his first year under his belt.

Muhtar had pulled strings to get his brother assigned to the governor’s detail, and this was the first time they’d worked together. Escorting Governor Zailik to the airport was a routine, inconsequential assignment. While waiting for the motorcade to get underway less than an hour earlier, the brothers had been joking with one another, enjoying their sibling camaraderie as they argued over who would be the first to get laid after they hit the discos later that night.

Suddenly, everything had changed.

“I thought this was supposed to be a walk in the park,” Ashar said. It was meant to be a wisecrack, but there was an edge in his voice. He idled his motorcycle and planted his boots on the road as he grabbed for the police-issue 9 mm automatic pistol nestled in its holster.

Muhtar had his gun out and was pointing it at the mob. Like Ashar, he remained on his bike, left hand lightly on the clutch, ready to get back in gear at a moment’s notice. He glanced quickly over at his brother. Save for a couple of high-speed chases, this was Ashar’s first true taste of danger since he’d received his badge. Muhtar could sense a glimmer of fear in his brother’s demeanor.

“I guess some parks aren’t as safe as others,” Muhtar quipped, trying to sound nonchalant and put his brother at ease.

The mob before them slowly began to fan out. Most of the protestors had already been unnerved by the sight of the armed policemen. They receded en masse to the shoulder. However, several men and one young boy split off from the group and began to circle around the governor’s car as if hoping to reach the vehicle from behind. Meanwhile, nearly a dozen protestors—many of them women and young boys—held their ground in front of the motorcade, linking arms to form a human chain that stretched across the entire width of the road and out onto the shoulder. Those at the end of the line clutched rocks slightly larger than the one that had already been thrown.

“We want the governor!” one of the women shouted at the two officers.

“Tell him to show his face!” another cried out.

Muhtar lowered his gun slightly and forced himself to remain calm. He ignored their demands but tried to reason with them.

“Please,” he said, trying to make eye contact with as many of the demonstrators as he could, “there’s no sense letting this get out of hand. Just drop the rocks and move away from the road.”

The plea fell on deaf ears. Those blocking the road stayed where they were, arms entwined, and continued to demand an audience with Zailik.

Ashar was less tactful than his brother when he swiveled astride his bike to contend with those making a move toward the car’s unprotected rear flank.

“Don’t even think about it!” he shouted.

When the stray demonstrators ignored him and continued toward the car, Ashar fired a warning shot over their heads. Startled, the group scrambled back. One man stumbled into another, knocking loose a rock the second man had been preparing to throw. Together, they retreated to the shoulder and rejoined the others, content, for the moment at least, to merely hurl insults at the man inside the car.

“The governor drives in a fancy limousine while we have no running water!” one taunted. “When will we have new homes instead of having to live out of tents and boxes?”

Another bellowed, “And what about those GAM workers he had executed the other night? Explain that, Governor!”

“If you have a problem with the governor, take it up at the ballot box!” Ashar snapped. “Not here!”

Muhtar whirled on his bike and shouted at his brother, “Don’t antagonize them! Just do your job!”

Ashar nodded and fell silent. Muhtar could see that his brother’s gun hand was trembling slightly, as were his knees, which were pressed close to the sides of his idling motorcycle. Muhtar knew that Ashar had gone through crowd-control drills during his training at the police academy, but in the heat of the moment his brother had clearly reverted to his hothead instincts.

“Just relax, Ashie,” Muhtar called out. “Don’t rile them up and we’ll get through this.”

Ashar continued to nod, but Muhtar was concerned. If his brother’s uneasiness was as obvious to the mob as it was to him, things could easily go from bad to worse in an instant.

By now a small delivery truck and a minivan were coming up behind the governor’s car. Both vehicles slowed to a stop. The minivan’s driver, like those in the cars that moments ago had been coming from the other direction, quickly assessed the situation and thought better of trying to move past the confrontation. Veering off the road for a moment, the van turned around and doubled back toward Banda Aceh. The driver of the truck was apparently not about to let matters throw him off schedule. After the van had passed him, he drove forward, picking up speed as he moved into the oncoming lane as if intent on passing the governor’s car. However, when a hurled rock smashed through the passenger side of the front windshield, just missing him, the man had second thoughts. He slammed on his brakes, then jammed the truck into Reverse and backed down the road a good thirty yards before making a quick three-point turn. Like the driver of the minivan before him, he retraced his route back to the city.

The motorcycle officers, meanwhile, remained on their bikes and kept a wary vigil over the protestors. Pistols outstretched before them, they fanned the weapons steadily from side to side in an effort to keep the mob at bay. It looked to Muhtar as if he’d gotten through to his brother. Ashar’s visible fidgeting had stopped and he seemed locked in to his police mentality, forearms rigid as he continued to keep his gun trained on the demonstrators. Muhtar was relieved. Though they were clearly outnumbered, he felt certain they would keep the upper hand so long as they gave the sense of being in control.

There was, however, the matter of the human chain that continued to block their way to the airport. No one had moved, and the man on the right end of the chain was still holding the rock Muhtar had told him to drop. The man at the other end of the line had only partially complied with the order; his rock had gone through the windshield of the now-retreating delivery truck.

“Put the rock down and everyone move off the road!” Muhtar told the group again, this time with more authority.

The demonstrators held their ground.

“We want answers!” one of the women shouted, raising her shrill voice to make certain the mob could hear it over the drone of the motorcycles. She pointed past the officers at the car, adding, “Tell that coward to show his face and give him to us!”

As she’d hoped, the woman’s harangue rallied the mob. Once again they began to chant and jeer. Another rock and several ears of corn bounded off the car, and Muhtar grimaced when a small, flat stone struck him squarely on the shoulder.

“Zailik’s a coward!” someone in the crowd howled. Some began to clap their hands in rhythm, as if at a sporting event. “Zailik’s a coward! Zailik’s a coward!”

Drawn by the commotion, more residents of the tent city began to emerge from their dingy quarters and head toward the road. Some had already grabbed tools and makeshift clubs, and several others paused along the way to pick up more rocks.

“Not good,” Muhtar murmured under his breath, refusing to visibly acknowledge the stinging welt on his shoulder.

Concerned the balance would soon shift out of their favor, the two brothers, without taking their eyes off the growing mob, spoke hurriedly to one another, trying to determine the best course of action. There was no way they were going to let Zailik out of the car—it was too dangerous and both brothers doubted there would be anything the governor could say to diffuse the situation. Ashar thought their best chance was to proceed with the motorcade in hopes the demonstrators would scramble out of the way once they realized their bluff was being called. Muhtar, however, was concerned about the possible ramifications if the crowd failed to move and some of them wound up being struck by their motorcycles.

“They put women and children out there for a reason,” Muhtar explained. “We run in to any of them and we’ll have a riot on our hands.”

“If we wait around for this mob to get any larger, all hell is going to break loose anyway,” Ashar countered, allowing his anger and frustration to override his earlier fears. “I say we head out and pick up speed as fast as we can, and whatever happens—”

“Wait!” Muhtar held a hand up to silence his brother. He stole a glance over his shoulder and peered back over the roof of the car. Ashar did the same.

“Finally!” the younger brother called out.