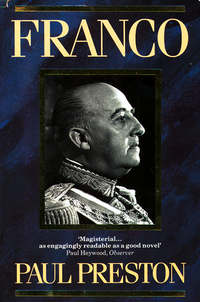

Franco

By 17 September 1921, Berenguer was able to order a counter-attack to recoup some of the territory lost. The Legion was once more in the vanguard. On the first day of the offensive, near Nador, Millán Astray was seriously wounded in the chest. He fell to the ground shouting ‘they’ve killed me, they’ve killed me’ then sat up to shout ‘¡Viva el Rey! ¡Viva España! ¡Viva la Legión!’. As stretcher-bearers came to carry him away, he handed over command to Franco.

When the young major and his men entered Nador, they found heaps of the unburied, rotting corpses of their comrades killed six weeks earlier. Franco wrote later that Nador, with the bodies lying in the midst of the scattered booty of the attackers, was ‘an enormous cemetery’.99 In the following weeks, he and his men were used in many similar operations, taking part in the recapture of Monte Arruit on 23 October. He saw no contradiction in the fact that, although he approved of the atrocities committed by his own men, he was appalled by the mutilation of the hundreds of corpses of Spanish soldiers found at Monte Arruit. He and his men left Monte Arruit ‘feeling in our hearts a desire for revenge, for the most exemplary punishment ever seen down the generations’.100 Franco himself recounted that, on one occasion during the campaign, a captain ordered his men to cease firing because their targets were women. One old Legionarie muttered ‘but they are factories for baby Moors’. ‘We all laughed’, wrote Franco in his diary, ‘and we remembered that during the disaster [at Melilla], the women were the most cruel, finishing off the wounded and stripping them of their clothes, in this way paying back the welfare that civilization brought them.’101

On 8 January 1922, Dar Drius fell to Berenguer’s column and much of what had been lost at Annual had been recaptured. Franco was indignant about the fate of Spanish soldiers massacred by the Moors at Dar Drius in 1921 and outraged that the Legion was not permitted to enter the village and take its revenge.102 However, they had their chance a few days later. An incident took place which led the press in Galicia to praise ‘the sang froid, the fearlessness and the contempt for life’ of the ‘beloved Paco Franco’. A blockhouse near Dar Drius was attacked by tribesmen and the defending legionãrios were forced to appeal for help. The Commander of the Spanish forces in the village ordered the entire detachment of the Legion there to go to their aid. Franco said that twelve would be enough and asked for volunteers. When the entire unit stepped forward, he chose twelve and they set off. The attack on the blockhouse was driven off. The next morning Franco and his twelve volunteers returned carrying ‘as trophies the bloody heads of twelve harqueños (tribesmen)’.103

When occasional leave permitted, Franco would visit Carmen Polo in Asturias. On these trips to Oviedo, as an ever more celebrated military hero, he was a welcome guest at the dinner parties of the local aristocracy. His presence was entirely compatible with a reverence for the nobility which would remain constant throughout his life.104 Here, as he socialised, he began to make contacts which would be useful in later life and he also began to make an investment in his public image which suggests the scale of his ambition. The press began to seek him out. In interviews, speeches made at banquets given in his honour and in his publications, he began consciously to project the image of the selfless hero. Shortly after he had taken over command of the Legion from Millán Astray, Franco had received a telegram of congratulations from the Alcalde (mayor) of El Ferrol. In the heat of battle, he found time to make a self-deprecatory reply: ‘The Legion is honoured by your greeting. I merely fulfil my duties as a soldier. An affectionate greeting to the town from the legionarios’.105 It was typical of Franco’s perception of himself at the time as the brave but self-effacing officer who is interested only in his duty. It was an image in which he believed implicitly and also one which he made some effort to project publicly. On leaving an audience with the King in early 1922, he told reporters that the King had embraced him and congratulated him on his success commanding the Tercio during Millán Astray’s absence: ‘What he has been said about me is a bit exaggerated. I merely fulfil my duty. The rank-and-file soldiers are truly valiant. You could go anywhere with them’.106 It would be wrong to say that when Franco spoke in such terms he was merely being cynical. There is little doubt that the young major sincerely saw himself in the Beau Geste terms of his own diary. Nonetheless, his behaviour in interviews and the fact that he published the diary in late 1922, freely giving away copies of it, suggest an awareness of the value of a public presence in the longed-for transition from hero to general.

* Francisco in memory of his paternal grandfather, Hermenegilda in memory of his paternal grandmother and in honour of his godmother, Paulino in honour of his godfather and Teódulo because he was christened on the feast of Saint Teódulo.

† There has been much idle speculation that his family was Jewish, on the basis of his appearance and because both Franco and Bahamonde are common Jewish surnames in Spain.

‡ Indeed, after Franco’s death, there were press revelations concerning Nicolás’s relationship in Manila with a fourteen-year-old girl, Concepción Puey, with whom he was said to have had an illegitimate son, Eugenio Franco Puey, who made himself known to Francisco Franco in 1950 – Opinión, 28 February 1977; Interviu, No. 383, 14–20 September 1983.

* Nicolás was born 1 July 1891, Pilar 27 February 1895 and Ramón 2 February 1896.

* Often he would join her in the difficult trek up the Pico Douro to the east of El Ferrol to pray to the Virgen de Chamorro in fulfilment of promises she had made in her prayers for his safe return.

* ‘Pacón’ means ‘big Frank’ which he was always called to distinguish him from Franco, who was known in the family as ‘Paquito’ or ‘little Frank’.

* In retrospect, he nurtured considerable resentment about his failure to receive the Gran Cruz for what happened at El Biutz. Forty-five years later, when he reconstructed the episode, he said that the wound had been to the liver rather than the lower abdomen, which might suggest some sensitivity about its alleged consequences for his masculinity. He claimed that, despite the gravity of the wound, he had heroically continued directing operations from his stretcher. In this fanciful recollection, he had missed the medal only because the doctor who attended him had reported later that he had been on the verge of collapse, in the mistaken belief that this would strengthen his case for the award. As it was, according to Franco, this led the adjudicators to conclude that his state of health would not have permitted him to continue in command. Ramón Soriano, La mano izquierda de Franco (Barcelona, 1981) pp. 141–2.

II

THE MAKING OF A GENERAL

1922–1931

FRANCO WAS beginning to evince signs of cultivating his public image, but he was genuinely popular with his men because of his methodical thoroughness and his insistence on always leading assaults himself. He was a keen advocate of the use of bayonet charges in order to demoralize the enemy. With his exploits well reported in the national press, he was being converted into a national hero, ‘the ace of the Legion’. The rotund and plain-speaking General José Sanjurjo, himself one of the heroes of the African campaign and Franco’s superior officer, said to him ‘you won’t be going to hospital as a result of shot fired by a Moor but because I’m going to knock you down with a stone the next time I see you on horseback in action’.1

In June 1922, Sanjurjo recommended Franco for promotion to Lieutenant-Colonel for his role in the recapture of Nador. Because enquiries were still being held into the disaster of Annual, the request was turned down. Nevertheless, Millán Astray was promoted to full colonel and Sanjurjo himself to Major-General. Franco merely received the military medal and remained a Major. Outraged by civilian criticisms of the Army and by indications that the government was contemplating withdrawal from Morocco, Millán Astray made a number of injudicious speeches and was removed from command of the Legion on 13 November 1922. To his chagrin, Franco was not invited to take his place since, still a major, he was too junior. Command was given instead to Lieutenant-Colonel Rafael de Valenzuela of the Regulares. Having been passed over for command, Franco then left the Legion. For the man who had built it up from scratch with Millán, the prospect of being second-in-command to a newcomer must have seemed unacceptable.2 He requested a mainland posting and was eventually sent back to the Regimiento del Príncipe in Oviedo.

To the dismay of most Army officers, the collapse at Annual reinforced the pacifism of the Left and diminished the public standing of both the Army and the King. Alfonso XIII was widely suspected of having encouraged Silvestre to make his rash advance.3 In August 1921, General José Picasso had been appointed to head an investigation into the defeat. The Picasso report led to the indictment of thirty-nine officers including Berenguer, who was obliged to resign as High Commissioner on 10 July 1922. Throughout the autumn of 1922, the Picasso report was the object of hostile scrutiny by a committe of the Cortes, known as the ‘Responsibilities Commission’, set up to examine political responsibilities for the disaster. The brilliant Socialist orator Indalecio Prieto denounced the corruption which had weakened the colonial Army and so ensured that Silvestre’s temerity would turn into overwhelming defeat. The Socialist deputy called for the closure of the military academies, the dissolution of the quartermasters corps and the expulsion from the Army of the senior officers in Africa. His speech was printed as a pamphlet and one hundred thousand copies were distributed free of charge.4

Berenguer had been replaced by General Ricardo Burguete, under whom Franco had served in Oviedo in 1917. Burguete as High Commissioner followed government orders to attempt to pacify the rebels by bribery rather than by military action. On 22 September 1922, he made a deal with the now obese and burnt-out El Raisuni whereby, in return for controlling the Jibala on behalf of Spain, he was given a free hand and a large sum of money. Since he was already under siege in his headquarters at Tazarut in the Jibala, El Raisuni’s power might have been squashed definitively had the Spaniards had the imagination and daring to occupy the centre of the Jibala. The policy of accommodation was a major error. Spanish troops were withdrawn from the territory of a man on the verge of defeat. He was enriched and his reputation and power inflated.

Burguete’s aim was to pacify the tribes in the west in order to have more freedom in his efforts to crush the altogether more dangerous Abd-el-Krim in the east. After first pursuing negotiations with him for the ransom of Spanish prisoners of war, Burguete passed to the offensive in the autumn. Burguete intended to use, as his forward base, the hill-top fortified position of Tizi Azza, to the south of Annual. However, before his attack could get under way, the Rif tribes struck at the beginning of November 1922. Safely ensconced in the slopes above the town, they fired down on the garrison causing two thousand casualties and obliging the Spaniards to dig in for the winter.5

The worsening situation in Morocco and the compromises pursued by Burguete may have convinced Franco that he was right to have left the Legion, whatever his reasons might have been. He was showered with honours as he passed through Madrid en route to Asturias. The King bestowed on him the Military Medal on 12 January 1923 and the honour of being named gentilhombre de cámara, one of an élite group of military courtiers.6 Franco was also the guest of honour at a dinner given by his admirers.

He was also the subject of an immensely flattering and revealing profile written by the Catalan novelist and journalist Juan Ferragut. It constitutes a portrait of Franco at the point when, with marriage around the corner, heroism was giving way to a more calculated ambition.* In Ferragut’s profile, there can still be heard the tone of the eager man of action which would soon disappear from Franco’s repertoire. Nevertheless, the clichéd patriotism and romanticised heroism of many of his remarks suggest that the persona of the intrepid desert hero was not entirely natural and spontaneous. When asked why he had left Morocco, Franco replied ‘because we aren’t doing anything there anymore. There’s no shooting. The war has become a job like any other, except that it’s more exhausting. Now all we do is vegetate.’ There was a contrived element about Franco’s answers which suggested an intense consciousness of his public image. When Ferragut asked him if he liked action, the thirty year-old Major replied ‘yes … at least up to now. I believe that a soldier has two periods, one of war and one of study. I’ve done the first and now I want to study. War used to be more simple; all you needed was heart. But today it is more complicated; it is, perhaps, the most difficult science of them all’. Ferragut described him as boyish: ‘his sunburnt face, his black, brilliant eyes, his curly hair, a certain timidity in his speech and gestures and his quick and open smile make him seem like a child. When he is praised, Franco blushes like a girl who has been flattered.’ He brushes aside the praise, as befits a hero, ‘but I’ve done nothing really! The dangers are less than people think. It’s all a question of endurance’.

Asked about his most emotional memory of the war, he replied ‘I remember the day at Casabona, perhaps the hardest day of the war. That day we saw what the Legion was made of. The Moors were pressing strongly and we were fighting at twenty paces. We had a company and a half and we suffered one hundred casualties. Handfuls of men were falling, almost all wounded in the head or the stomach, yet our strength never wavered for a second. Even the wounded, dragging themselves along covered in blood, cried ‘¡Viva la Legión! Seeing them, so manly, so brave, I felt an emotion which choked me.’ Asked if he had ever felt fear, he smiled as if puzzled, and shyly replied ‘I don’t know. No one knows what courage and fear are. In a soldier, all this is summed up in something else: the concept of duty, of patriotism.’ The romantic note continued with references to the anxious vigils of his mother and bride-to-be. Ferragut asked him directly, ‘Are you in love, Franco?’ to which the affable interviewee replied ‘¡Hombre!, what do you think? I’m just off to Oviedo to get married.’7

On 21 March 1923, Franco arrived in Oviedo where his exploits ensured that he would be feted. At the beginning of June, local society turned out in force for a banquet at which he was presented with a gold key, the symbol of his recently acquired status as Gentilhombre de cámara, purchased for him after a local subscription. The King had still not granted the reglamentary permission for his wedding. Since this was a mere formality, the ceremony was being planned for June. However, while Carmen and Francisco were waiting to hear from the Palace, their plans suffered another reversal. Franco had gone to El Ferrol where he spent most of May with his family. In early June, Abd el Krim launched another attack on Tizi Azza, the key to the outreaches of the Melilla defence lines. If Tizi Azza fell, it would have been relatively easy for other Spanish positions to collapse in a domino effect. On 5 June 1923, the new commander of the Legion, Lieutenant-Colonel Valenzuela, was killed in a successful action aimed at breaking the siege.8

An emergency cabinet meeting three days later, on 8 June 1923, decided that the most suitable replacement for Valenzuela was Franco. The Minister of War, General Aizpuru, telegrammed to inform him that he had been promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel with retrospective effect from 31 January 1922 and that the King had bestowed command of the Legion upon him. His marriage would have to be postponed again. The ambitious Carmen may have found consolation for the loss of her bridegroom in his promotion, the signs of royal patronage and the enormous local prestige that he thereby enjoyed, although, interviewed in 1928, she talked of her anxieties while he was away and of his principal defect being his love for Africa.9

Prior to leaving Spain, Franco was the guest of honour at banquets in both the Automobile Club in Oviedo and at the Hotel Palace in Madrid. One of the principal Asturian newspapers dedicated an entire front page to his promotion and his prowess, complete with extravagant tributes from General Antonio Losada, the military governor of Oviedo, from the Marqués de la Vega de Anzó and other local dignitaries.10 Interviewed on arrival at the Automobile Club banquet on the evening of Saturday 9 June, Franco showed himself to be the public’s ideal young hero, dashing, gallant and, above all, modest. He dismissed talk of special bravery and showed himself perplexed by all the fuss that was being made. Clearly conscious of the dash he was cutting, he interrupted the journalist’s attempted eulogy by saying ‘I just did what all the Legionaires did, we fought with a desire to win and we did win’. A discreet reminder of what he was leaving behind brought a delicate glimpse of emotion which Franco quickly put behind him. The journalist remarked sycophantically ‘how the brave Legionaires will rejoice at your appointment!’. Franco replied ‘Rejoice? Why? I’m an officer just like …’, only to be interrupted by a passing ex-Legionaire who said ‘say yes, that they will all rejoice, of course they will rejoice’. Like a hero of romantic fiction, Franco replied with a modest laugh, saying ‘Don’t go overboard. Yes, you’re right, the lads care for me a lot.’

The interview ended with Franco being asked about his plans, at which he gave another hint of the sacrifice he was having to make. He replied with a curious mixture of virile enthusiasm and self-regarding pomposity: ‘Plans? What happens will decide that. I repeat that I am a simple soldier who obeys orders. I will go to Morocco. I will see how things are. We will work hard and as soon as I can get some leave I will come back to Oviedo to … to do what I thought was virtually done, which for the moment duty prevents, taking precedence over any feelings, even those with roots deep in the soul. When the Patria calls, we have only rapid and concise response: ¡Presente!’11 There is no doubt that this, and other interviews from this period, show an altogether more attractive figure than the one that Franco was later to become, in large measure as a consequence of the corrupting influence of constant adulation. The Minister of War and future President of the Second Republic, Niceto Alcalá Zamora, thought Franco’s near contemporary and rival, Manuel Goded, a more promising officer than Franco. However, he liked Franco’s air of modesty, ‘the loss of which when he became a general damaged him significantly’.12

Within a week of passing through Madrid, Franco had taken up his new command in Ceuta and was soon in the thick of the action. Shortly after Franco’s arrival in Africa, Abd el Krim followed up his attack on Tizi Azza with another on Tifaruin, a Spanish outpost near the River Kert to the west of Melilla. Nearly nine thousand men besieged Tifaruin and they were dislodged on 22 August by two banderas of the Legion under Franco’s command.13

Such was the accumulated military discontent about what was perceived as civilian betrayal of the Army in Morocco that since early in 1923 two groups of senior generals, one in Madrid and the other in Barcelona under Miguel Primo de Rivera, had been toying with the idea of a military coup.14 The incident which triggered it off took place on 23 August. There were a number of public disturbances in Málaga involving conscripts being embarked for Africa. Civilians were jostled and Army officers assaulted. Some of the recruits were merely drunk, others were Catalan and Basque nationalists making political protests. Order was finally restored by the Civil Guard. An NCO in the Engineering Corps (suboficial de ingenieros), José Ardoz, was killed and the crime was attributed to a gallego, Corporal Sánchez Barroso. Sánchez Barroso was immediately tried and sentenced to death. Since Annual, there had been a widespread public revulsion against the Moroccan enterprise and, in consequence, there was a huge outcry about the death sentence. On 28 August, Sánchez Barroso was given a royal pardon, at the request of the cabinet. The officer corps was outraged by the humiliation of the Málaga incidents, by the subsequent public rejection of their cause in Morocco and by what they saw as the slight involved in the pardon.15

On 13 September, the Falstaffian eccentric General Miguel Primo de Rivera launched his military coup supported by the garrisons of his own military region of Catalonia and by that of Aragón, under the control of his intimate friend General Sanjurjo. There is considerable debate about the King’s complicity in the coup. What is certain is that he acquiesced in the military demolition of the constitutional monarchy and happily embarked on a course of authoritarian rule. After six years of sporadic bloodshed and instability since 1917, and the fashionable ‘regenerationist’ calls for an ‘iron surgeon’, the Military Directory set up by Primo de Rivera met with only token resistance and, given widespread disillusion with the caciquista system, much benevolent expectation.16 Despite the mutual admiration which, at this stage of their careers, united Franco and Sanjurjo, neither Franco nor most of the officers of the Legion were particularly enthusiastic about the coup. They regarded most of the officers who supported Primo as primarily members of the Juntas de Defensa and therefore enemies of promotion by merit. In addition, they were fully aware of the belief of Primo himself that Spain should abandon her Moroccan protectorate.17 It is clear, however, that Franco had no objections in principle to the military taking political power, particularly as royal approval was quickly forthcoming. In any case, his mind was on other things – his new command and his impending marriage, for which royal permission had finally been granted on 2 July.18

The thirty year-old Francisco Franco was married to the twenty-one year-old María del Carmen Polo in the Church of San Juan el Real in Oviedo at midday on Monday 22 October 1923. His fame and popularity as a hero of the African war ensured that substantial crowds of well-wishers and casual onlookers would gather round the church and on the pavements of the streets traversed by the wedding party. By 10.30 a.m., the Church was full and the crowd had spilled out and packed the surrounding streets. The police had difficulty maintaining the flow of local traffic. As befitted his position as a gentilhombre de cámara, Franco’s padrino (best man) was Alfonso XIII, by the proxy of the military governor of Oviedo. General Losada took Carmen’s arm and they entered the Church under the royal canopy (palio). That honour, combined with Franco’s growing reputation, was reflected in the fact that his marriage was reported in the society pages not only of local newspapers but also of the national press. A bemedalled Franco wore the field uniform of the Legion. The ceremony was carried out by a military chaplain while the organ played Franco’s choice of military marches. On leaving the church, the couple were greeted by wild cheering and applause. The crowd followed the cars back to the Polo house and continued to cheer.19 The marriage constituted a major social occasion in Oviedo, the centre-piece of which was a spectacular wedding banquet.20 Franco’s father, Nicolás Franco Salgado-Araujo, was not present. As might have been expected, it was to be a solidly enduring, if not a passionate, marriage.* Five years later, Carmen would recall her wedding day, ‘I thought I was dreaming or reading a beautiful novel … about me’.21 Among the mountains of telegrams was a collective greeting from the married men of the Legion and another from a Legion battalion which welcomed Carmen as their new mother.22