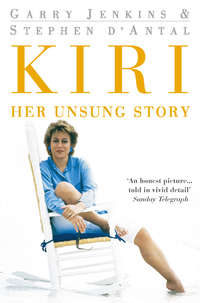

Kiri: Her Unsung Story

Approaching her forty-seventh birthday, Nell, the mother of two children from a previous marriage, was now too old to bear Tom a child. The couple had decided to adopt instead. According to their own account, passed on to their daughter later, Tom Te Kanawa was particularly keen to adopt a boy and rejected Claire on first meeting her. Unable to find another home for the baby, however, the social worker persisted. When Claire was taken to Grey Street for a second time Tom had been smitten by the dusky-skinned little girl with huge limpid eyes. He and Nell agreed to adopt her as their daughter.

As the legal formalities were completed Tom and Nell were asked to choose the child’s new name. Nell had agreed with Tom’s idea of calling the little girl Kiri, after Tom’s father, a Maori name meaning ‘bell’ or ‘skin of the tree’, depending on the dialect. For her other names they chose Jeanette, one of Nell’s own middle names, and Claire, the only name they had heard the social workers use when referring to the child. For decades to come, the name her birth mother had chosen for her would remain Kiri Jeanette Claire Te Kanawa’s sole link with her troubled past.

As she handed her baby over to the town’s social services, Noeleen Rawstron had accepted that she could have no say in choosing the family who would become Claire’s parents. As she dwelled on her daughter’s fate back in Tokomaru Bay, she would have hoped for a life filled with love and security. On a deeper level, her instincts may have wished for a home and a family background that fitted the little girl’s own complex beginnings. In time Noeleen would come to discover the identity of the couple who had taken her daughter in, but she would never appreciate quite how alike Claire’s real and adopted parents were.

In the course of a colourful and eventful life, the redoubtable Mrs Tom Te Kanawa had found herself addressed by any number of names, not all of them charitable. At birth on 14 October 1897, she had been christened Hellena Janet Leece. Since then she had been addressed at different times, and with varying degrees of happiness, as Mrs Alfred John Green and Mrs Stephen Whitehead. In electoral and postal directories around the North and South Islands of New Zealand, her unusual Christian name had been rearranged as Ellenor, Eleanor and even Heleanor. It was little wonder she insisted new friends simply call her Nell. To her family and the boarders she took in at her guest house there was little cause for confusion, however. To them she was The Boss – and she always would be.

A boisterous, ruddy-cheeked woman with a heart – and a temper – to match her oversized frame, Nell Te Kanawa cast her considerable shadow over every aspect of life at the house that became baby Claire Rawstron’s new home. During the formative years of her new daughter’s life she would be its dominant – and at times overwhelmingly domineering – force. She would not thank her for it until later in life. Yet without The Boss, it is unlikely Kiri Te Kanawa would have left the town of Gisborne, let alone the North Island of New Zealand.

Like Thelma and Noeleen Rawstron, Nell Te Kanawa had endured a life of early hardship. She was born in the gold-mining town of Waihi in the Bay of Plenty. Nell’s mother, Emily Leece, née Sullivan, was the daugter of a miner, Jeremiah Sullivan. She was one of fifteen children Emily bore with her husband, another miner, John Alfred Leece, originally from Rushen on the Isle of Man. Like many men of his generation, John Leece dreamt of making a fortune at Australasia’s largest gold mine. Instead, however, his life seems to have disintegrated there. It is unclear whether Emily Leece was widowed or divorced her husband. What is certain is that when Hellena was a teenager her mother uprooted the family to the town of Nelson, at the northerly tip of the South Island, where she set up a new life without John Leece.

‘Nell’, as everyone called Hellena, was less than lucky in her own relationships with men. It was certainly not for the lack of trying.

She had wasted little time in finding a husband. She had been just eighteen when she married Alfred John Green, a twenty-year-old labourer from Hobart. Nell had been employed as a factory worker in the town and living with her mother, now re-married to a Nelson labourer called William John Staines. Emily and her new husband were the witnesses at the wedding, held at the town’s Catholic Church on Manuka Street on Monday, 1 November 1915.

Within four years, the Greens had two children; Stan, born in 1916, and Nola, born three years later. Around the time of Nola’s arrival in the world the family moved to a farm in the remote community of Waimangaroa, outside Westport on the stormy west coast of the South Island where Nell’s parents had been married. Life on the land seems to have proven too hard and soon the family were living in the tiny village of Denniston, where Alfred had found work as a carpenter. The move was no less of a failure. With Stan and Nola, Nell left her husband and Denniston for Gisborne on the East Cape of the North Island. She and Alfred Green were divorced in October 1933.

The divorce inspired a new energy in Nell’s life. In the years that followed, she often proclaimed that she had arrived in Gisborne with nothing but ‘two suitcases and two kids’. With the determination that would characterise her later years, she began the process of building a more secure life for herself and her family.

With Stan and Nola and a relation of her mother’s, Irene Beatrice Staines, she moved into a large boarding house at 161 Grey Street. It was while lodging here that, according to some, Nell began performing illegal abortions. Her services were much in demand in the busy coastal town where too many young women found themselves compromised by visiting sailors and other transient workers. As discreet as she was efficient, she apparently found much of her custom within members of the Gisborne’s growing Greek and Italian immigrant population.

Nell had soon found herself a new husband too. Around the time her first marriage was dissolved she met Stephen Whitehead, a forty-eight-year-old widower from Gisborne. Nell and Whitehead, a bicycle dealer and mechanic, were married at the registrar’s office in Gisborne on 8 August 1935. The marriage proved childless, short-lived and somewhat scandalous. It was Kiri herself who later suggested Nell’s second marriage had left her in disgrace, both with her family and the Catholic Church. ‘There had even been talk of excommunication,’ she remembered. If the exact details of Nell’s shame are unclear, it is not difficult to imagine the outrage her backstreet operations would have provoked if they had become known within the church.

From baby Claire’s perspective, at least, there were more encouraging threads linking the lives of Nell Te Kanawa and Noeleen Rawstron. Of all the parallels, perhaps none would prove so significant as the fact that both Nell and Noeleen had found themselves involved in mixed-race relationships.

As her second marriage headed towards divorce, Nell had met and fallen in love with a soft-spoken, deeply reserved truck driver also lodging at Grey Street. In Atama ‘Tom’ Te Kanawa, it turned out, she had found the ideal man with whom to reinvent herself.

Tom Te Kanawa’s family originated from the west coast of the North Island, near Kawhia Harbour and the community of Kinohaku. His bloodlines led directly back to a legendary Maori figure, Chief Te Kanawa of one of the Waikato tribes, the Maniapoto. Chief Te Kanawa’s primary claim to a place in New Zealand’s history rests on his exploits in the Maori wars of the 1820s. In 1826, Te Kanawa and another chieftain, Te Wherowhero, had ended the ambitions of the region’s most feared warlord, Pomare-nui, by ambushing his canoe and murdering him. According to Maori folklore, the two chiefs had then cooked and eaten their vanquished rival. As the gruesome ritual had been carried out, strange, yellow granules had been found inside his stomach. Thus, corn is said to have arrived in the Waikato region.

Tom was one of thirteen children born to a farmer, Kiri Te Kanawa, and his wife Taongahuia Moerua. By the time Tom, his parents’ fourth child and third son, arrived in the world in 1902, the Te Kanawa family had moved from Kawhia inland to the lush green hills above the small towns of Otorohanga and Waitomo. Tom spent the formative years of his childhood in a community built around the family meeting place, or marae, Pohatuiri. The community was a remote collection of earth-floored houses made from punga logs – the trunks of a native fern tree – set miles from the nearest roads. His early life there was rooted in a simple, self-sufficient lifestyle that had served the Maori people for centuries.

Tom’s younger brother, Mita, later wrote of the Te Kanawas’ way of life in a privately published history. He remembered Pohatuiri as a ‘very busy community’, and looked back with affection at ‘the closeness, unity and warmth of everyone’ who shared their world. The fertile land around Pohatuiri provided almost everything they needed. The families bought in only sugar, salt, flour, tobacco and alcohol to supplement their home-brewed supplies. Seafood was often provided by family members from Kawhia. In this land of milk and honey, the depression that afflicted the rest of the world in the 1930s passed almost unnoticed.

The highlights of each year were the huis, or feasts, prepared communally. ‘Our family homestead was situated just above where the spring and the orchard trees were. Whenever there as a hui approaching, everyone planned on the preparation for the function,’ Mita wrote. ‘Each family group looked after certain duties, but we all helped each other. Fruit picking was done by all of us – we collected the fruit and our kuia [elder women] would be busy with the making of jams, pickles, sauces, preserves and homebrews.’

Both Tom’s parents were God-fearing individuals. Taongahuia’s family were staunch members of the Christian Ratana movement, named after its founder Bill Ratana, a farmer who had become convinced of his pastoral role after witnessing visions in 1919. Kiri was never slow to chastise younger members of the family overheard using bad language. It was a community steeped in the Maori language, and its tradition of passing its history on orally rather than the written word. According to the family, Kiri was the possessor of a fine singing voice. ‘Kiri and his wife couldn’t speak English at all. They didn’t really have to up there,’ said Kay Rowbottom, Tom’s niece, the daughter of his sister Te Waamoana. ‘They maybe could read a little but not speak it, perhaps just a few basic words.’

At school, however, Tom was introduced to the harsh realities of New Zealand life. Tom and his siblings were taught English as a second language and were banned by statute from any use of their native tongue. ‘In that era they would have been beaten with a leather strap for speaking Maori,’ said Kay Rowbottom.

Tom’s childhood in the hills eventually came to an end when he was sent to a foster mother, Ngapawa Ormsby, in the town of Otorohanga. The arrangement was far from unusual. ‘Kids were fostered out as workers,’ said Kay Rowbottom. ‘They were like slaves. In a lot of cases, the girls worked in the houses and the boys on the land.’ Tom’s unhappiness at the arrangement was soon obvious, however. ‘I don’t think Tom enjoyed his time down there. I remember people talking about it years later.’

Tom went to a local school for both Maori and European (or Pakeha) children but, like all but the offspring of the wealthy, had no option but to leave at the age of twelve. Forced to find his own way in the world, he became increasingly estranged from the Maori family in which he had been raised. The death of his parents and the end of the old lifestyle at Pohatuiri, where the old community was slowly reabsorbed into the bush from which it had grown, only added to the distance between him and his siblings.

While the Te Kanawa family moved to the Moerua family’s marae at Te Korapatu, Tom decided to break away from his roots and move to Gisborne on the east coast. He arrived there in the late 1920s or early 1930s. It was while renting a room at 161 Grey Street that he met the formidable figure of Nell Whitehead.

On the face of it, at least, Tom and Nell made an unlikely couple. At the age of thirty-seven, Tom was five years Nell’s junior. He was as taciturn as she was ebullient. She had been married twice before, he had seemingly formed few, if any, lasting relationships. Yet against all the odds they seem to have conducted a whirlwind romance. They were married in Gisborne on 14 July 1939, only twenty-four days after Nell had been granted a decree absolute dissolving her second marriage.

In many respects Tom and Nell Te Kanawa were older, wiser and, in Gisborne terms at least, more financially secure versions of Jack Wawatai and Noeleen Rawstron. From the very beginning, they devoted their lives to giving their only daughter Kiri everything she could possibly want in life.

Perhaps Tom’s most significant gift was the name he chose for his baby girl. His choice of his father’s name served a dual purpose. In the short term the name short-circuited any arguments within the family over the child’s adoption into the Te Kanawa line. While fostering was a common practice among Maori, full adoption was rarer. Tom’s relations, notably his younger brother Mita, believed the Te Kanawa name was reserved for blood family and adoption diluted that exclusivity. ‘Mita didn’t like adopting kids,’ said Kay Rowbottom. ‘His only daughter Collen was fostered by him and his wife but they never adopted her. She was always known as Collen Keepa, her birth surname, and she’s no relation of the Te Kanawa family.’

Tom, who had been unhappy during his time as a foster child, was not about to condemn his only daughter to such limbo. Deliberately or otherwise, by handing on his father’s Christian name, a gift Maori tradition dictates can only be given once in a generation, he signalled to Mita and the other members of his family that baby Kiri was his own child. ‘They believed she was a blood daughter because Tom had given her his father’s name, Kiri,’ said Kay Rowbottom. In the long term, the distinctive name, and the heritage that went with it, would prove an incalculable asset. Kiri would come to draw on her Maori ancestry, even write a book, influenced by the magical elements of her roots. On a more practical level, she would appreciate too how it lent her a name and an image that would count for much when she left her native New Zealand.

As she herself put it years later: ‘It’s unique to be Maori, to sing opera, have a fantastic name; it’s all rather exotic and interesting. Better than being Mary Smith with mousy hair.’

Kiri arrived at Grey Street around the time that Nell became the house’s new, official owner in September 1944. The colonial style, white, weather-boarded house stood in the heart of the town, on a peninsula near the town’s docks and the estuary of the Turanganui River. Nell had paid £1,400* for the property, which had been repossessed from its previous owners by its mortgagees. When Nell had first arrived in Gisborne it had been a busy guest house run by a Miss Yates. By luck or judgement she took over as its new owner as Gisborne, a shipping centre for the frozen meat industry for more than sixty years, passed through one of the busiest periods in its history.

Gisborne, or Turanga-nui-Kiwa as it was then known, had been Captain Cook’s first port of call when he had landed in New Zealand in 1769. So unpromising was the greeting he received from the local Maori, he named the sweeping stretch of coastline it overlooked Poverty Bay. The modern settlement had been founded a hundred years later in 1870 and named after Sir William Gisborne, then Secretary for the British Colonies.

By the final years of World War II, Gisborne’s population had swelled to some 19,000 or so people. New Zealand’s links to its former colonial masters remained strong. When Great Britain declared war on Germany it had joined the effort immediately. ‘Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand,’ its Prime Minister, Michael Savage, had pledged. The nation’s navy was placed under Admiralty control and New Zealand’s pilots travelled to England to form the first Commonwealth squadron in the RAF.

A battalion of volunteer Maori troops was dispatched to the front line from where it would return garlanded with honours. While Mita Te Kanawa was among them, his brother Tom stayed behind to help maintain the flow of mutton, wool and food supplies that was among the loyal Kiwis’ greatest contribution to the war effort.

As New Zealand played quartermaster to the warring northern hemisphere, Gisborne’s harbour was filled with cargo ships bound for Britain and other parts of Europe. As it did so, its industrial base mushroomed. As well as freezing factories, the town became a centre for dairy, ham and bacon processing, tallow and woolscouring works, brewing, canning, hosiery and general engineering. Such would be its growth over the following decade that Gisborne would be officially recognised as a city in 1955.

For the young Kiri, the bustling quays were a place of endless fascination. She would make the short walk to the docks and stand for hours watching the ships sailing in and out, flocks of sea birds attached to their masts.

Her home at Grey Street was no less a source of fascination. In the grounds at the back Tom tended a few chickens, there was a disused tennis court and apricots, peaches and strawberries grew freely. At the front a huge, old pohutakawa tree, to be rigged with a swing later, stood outside the porch. The house stood opposite one of the town’s main ‘granaries’, or general stores, Williams and Kettle. The store had donated the Te Kanawas’ two cats, unimaginatively christened William and Kettle.

Given its central position, and the town’s hyperactivity, the Te Kanawa guest house was never short of boarders. Recounting her earliest memories later in life, Kiri realised she could barely remember a time when there were less than twenty people in the house. The one permanent fixture was an elderly boarder, known simply as ‘Uncle Dan’, who inhabited an upper storey bedroom he liked to call his ‘office’.

‘Every available space she could find Nell put someone in it,’ recalled one boarder, Myra Webster, sister of Nell’s son-in-law, Tom Webster. ‘Every little store shed was done up as a room. Upstairs she would have about four people crowded in each room. She wouldn’t turn anyone away,’ she added.

Nell’s head for business extended to a detailed knowledge of each tenant’s financial arrangements. ‘She always knew when their paydays were. She’d stand at the bottom of the stairs when they came home and she’d make sure they were paying up to date. Most of them were young Maori people who came down from the coast to work in Gisborne. She charged the going rate, about one pound ten a week, so she had a pretty good income.’

The healthy living the boarding house provided meant Nell could move away from her earlier sideline. According to one member of the family, Tom insisted that she stop performing abortions when they married. When he discovered she had defied him on one occasion, an enraged Tom grabbed his golf bag and broke each of his hickory-shafted clubs across his knee.

For Kiri as a child, the house – and its sprawling grounds – was a wonderland in which she could run free. Bedrooms climbed all the way to the third floor attic. Downstairs was dominated by a huge, farmhouse-style kitchen and dining room. At the front of the house, a lounge, complete with comfortable sofas and an upright piano, family portraits and Nell’s collection of knick-knacks, offered the only real refuge from the constant comings-and-goings. While the rest of the house was left in a ‘take us as you find us’ fashion, the lounge was kept spick and span for entertaining guests drawn from Nell’s ever widening social circle.

Nell’s social aspirations were clear to see. ‘Nell used to play croquet with a group of ladies at a club in Gisborne,’ remembered Myra Webster. ‘I think they enjoyed afternoon tea more than the croquet, but whenever these ladies came to the house, out would come the best china and all the dainty little trinkets and cakes.’

In his own way, Tom was upwardly mobile too. Unlike many of his family and the vast majority of the Maori population, he was in favour of assimilation into New Zealand’s dominant, white European culture. As he removed himself further from his family he immersed himself in the middle-class enclaves of the town, becoming a popular figure at the Poverty Bay Golf Club. ‘I think he wished he had a paintbrush and could paint himself white,’ one relation used to say.

His success in business only opened the doors wider. On his wedding certificate, Tom listed his profession as ‘winchman’. Since leaving school early he had worked on construction projects all along the east coast, specialising in driving trucks and operating cranes. With the contacts and cash he made from the most lucrative, blasting a road link to Gisborne via the previously impenetrable gorge of Whakatane, he had set up a small contracting company.

Tom, though no more than 5ft 10in, was a muscular and powerful man and prided himself on his physical strength and his capacity for hard work. ‘He had fingers like sausages, and these wonderful hands, worker’s hands,’ Kiri recalled once. ‘He never believed that he couldn’t dig a tree trunk out, lift a boat, lift anything because he was so strong.’

By the end of the 1940s he was able to build his own holiday home, a comfortable cabin, or ‘bach’, on the shores of Lake Taupo, a favourite New Zealand holiday destination in the heart of the North Island. Tom had always been famously industrious. In Kiri he had found a reason to work even harder. Nothing was too much trouble if it was for Kiri, the unquestioned apple of her father’s eye. When she was very young Tom built an elaborate dolls’ house complete with fitted windows, linoleum floors and a dressing table. ‘Kiri stayed in it for about a week, and then the old lady put a tenant in it,’ said Myra Webster.

In time Kiri came to value the Maori qualities bequeathed by both her natural and adoptive fathers. ‘I was given two marvellous gifts. One was white and one was Maori,’ she said later in life. It was not an opinion she voiced often as a young girl, however.

Kiri admitted later that Tom had ‘basically rejected the Maori side’ of his life. ‘My father would not speak Maori and I would not learn Maori because it was just not fashionable to do that,’ she said. ‘I was brought up white.’

Yet as Kiri took her first steps into a wider world, at St Joseph’s Convent School in Gisborne, her unmistakable heritage drew unwanted attention. Mixed race marriages were far from unusual in Gisborne. At St Joseph’s, however, Kiri found herself in more conservative company. She recalled once how her entire class had been invited to a grand birthday party at a well-to-do home in Gisborne. ‘They sent me home because I was the Maori girl.’ At the time, she claimed later, she was too young to notice, but Nell’s anger at the humiliation ensured the incident was burned into her memory. ‘My mother kept reminding me, and I thought, “Why does she keep reminding me?”’

The treatment meted out to Kiri and the two other Maori girls at St Joseph’s on another occasion left even deeper psychological scars. One day, without any warning, the three children were taken from school and forced to have a typhoid vaccination. ‘At that time in New Zealand, Maori children were considered to be dirty,’ Kiri wrote three decades later in Vogue magazine, the memory still painfully vivid. ‘It made me ill. I was on my back in a darkened room for two weeks afterwards. My mother was furious that she hadn’t been consulted and I never forgave the powers that be for doing that to me without bothering to find out that I came from a good clean home.’

At school, Kiri’s sense that she was somehow apart from other children was confirmed on an almost daily basis. Nell never appeared at the school gates to collect her, she recalled. ‘When it rained there would always be a little crowd of mothers outside the school with raincoats and umbrellas,’ she said once. ‘I always half expected her to be there but she never was. I don’t know why. She just didn’t bother, so I walked home in the wet.’