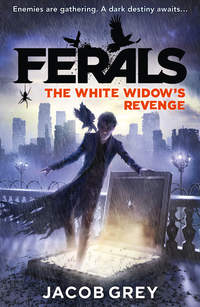

The White Widow’s Revenge

“Brave work, Vic,” he said. “All of you.”

The coyotes let out a collective noise, halfway between a purr and a growl.

“Fivetails!” said Crumb.

“Who?” said Pip, clearly as bewildered as Caw.

“Johnny Fivetails,” said the man, holding out a hand to the mouse feral.

Pip looked at it, blinking.

The man grinned then clapped him on the shoulder instead. “Still in shock, I guess. It was a hell of a fight.”

“What are you doing here?” said Crumb. “How did you—”

Sirens wailing in the distance cut him off.

“I’ll explain later,” said Johnny Fivetails. “Right now, we need to leave.”

Still reeling, Caw led the way to his house through the backstreets of Blackstone. The rain was falling hard, and he and Pip sheltered under the umbrella, while Crumb and the coyote feral followed behind. Crows and pigeons silently alighted on the buildings and the trees along the way at regular intervals. If there were any coyotes below, they were well hidden.

Caw glanced back and saw Johnny looking about and smiling, despite the rain.

“This place hasn’t changed much in eight years, has it?” he said.

“Not really,” said Crumb. He looked a little confused. “I thought you’d left Blackstone for good?”

“So did I,” said Johnny.

Caw muttered to Pip, “So do you know him?”

Pip shook his head. “I’ve heard of him though. The great Johnny Fivetails! Fought for us in the Dark Summer. No one’s seen him for ages.”

Johnny must have overheard. “Never liked staying in one place,” he said. “Always been like that.”

“So why are you back?” asked Crumb.

Johnny grinned, revealing dazzling white teeth, and pointed at Caw. “Because of this guy.”

“Me?” said Caw.

“Your fame travels, kid,” said Johnny. “I can’t believe I finally get to meet the crow talker who went to the Land of the Dead and returned! The hero who defeated the Mother of Flies! Hope you don’t mind me saying, but you don’t really look like a tough guy. Mind you, neither did your mum.”

The sudden mention of his mother caught Caw off guard. “You … you knew her?”

“Sure!” said Johnny. “Bravest woman I ever met. Beautiful too, but I was only twenty at the time.” He blushed. “Sorry – you probably don’t need to hear that about your mum.”

“It’s OK,” said Caw awkwardly. “Thank you, by the way – you saved us back at the bank.”

“Lucky I showed up,” said Johnny. “Never met a bison feral before, but we showed her who’s boss, right?”

“Right!” said Pip.

Crumb looked less impressed. “So you were just passing by?”

“Not quite,” said Johnny. “I’ve been in touch with Maddie. You know Maddie – the squirrel talker?”

“Madeleine,” said Crumb, with a brisk nod. “Yes, I know her.”

Caw sensed the temperature dip, and he felt sorry for Crumb. When Caw had been helping the pigeon feral shift his meagre belongings from his old hideout back to Caw’s place, an old photo had fallen out. It showed teenage Madeleine and Crumb on a fairground ride, arms round each other.

“Well,” Johnny carried on, clearly unaware, “she told me that there were some new ferals who don’t play by the rules. I heard something about a casino last night, and a bank raid today. I guessed it might be Pickwick’s place. Pretty fortunate, really.”

Crumb nodded. He looked a little shaken.

“Maddie – sorry, Madeleine –” continued Johnny, “is looking great. Finally out of that wheelchair – I’m so happy for her.”

Caw saw Crumb wince again. Time to change the subject.

“So are you staying in Blackstone?” he asked.

“I haven’t decided yet,” said Johnny. “I’m not great with decisions, to be honest. Hey, is it true you can actually, y’know, turn into a crow?”

Caw blushed.

“It’s true!” said Pip.

“That’s so awesome,” said Johnny. “You have to show me that trick.”

Caw hadn’t even tried it since his battle with the Mother of Flies, but he sensed the power lurking within him. “Er … sure,” he said.

“Where are you staying?” asked Crumb.

“Some dump by the river,” Johnny replied. “The lift doesn’t work and it smells bad, but at least it’s out of this rain!” He smoothed strands of damp hair back from his face.

They’d reached a crossroads. One route headed west towards Caw’s house, while another climbed towards the park in the north and the Strickhams’ place. Caw wondered how Lydia was. She was the first human friend he’d ever had – and the best – but he hadn’t seen her for over a fortnight. He missed having her around, smiling and cracking jokes. Lately it felt as though there wasn’t much to laugh about.

“Actually, I’ll say goodbye here,” said Johnny. “Need to find some food for the pack.” He held out his hand to Caw. “An honour to meet you, crow talker. I’m sure we’ll see each other around.”

Caw felt a little weird, but took it anyway.

Johnny shook firmly, staring at Caw. “You look so much like her, you know?”

Caw felt his cheeks reddening once more.

“Come to Caw’s!” said Pip. “There’s loads of room with us.”

Johnny put up his hands. “Oh, no. I couldn’t.”

“I’m sure Johnny wouldn’t want—” began Crumb.

“You must!” said Pip. “You just saved our lives.”

“I guess that’s up to Caw,” said the coyote feral. “It’s his place, after all.”

Crumb had fallen silent, but Caw thought Pip had a good point. And perhaps Johnny could tell him a bit more about his mother too.

“You’d be welcome,” he said.

Johnny shrugged. “That’s very kind of you, Caw. Is it the place your folks used to have? I think I even remember the way.” He pressed on ahead of them, whistling a happy tune.

As they walked to the house, Caw thought about the bank heist. A bison … He hadn’t noticed one of those on the roof when the Mother of Flies was creating her new army. He wondered what else had been up there – what other horrors awaited them.

And then he remembered something that Mr Silk had said.

“Those weren’t our orders …” Caw muttered.

“I’ve been wondering about that too,” said Crumb quietly. “It sounds like they have a new boss.”

“One of the other convicts?” asked Caw.

“Perhaps,” said Crumb, but he didn’t look convinced.

Caw shuddered as another possibility came to him. “You don’t think the Mother of Flies—”

“No way,” said Crumb quickly. “She’s in Blackstone Asylum. Her connection with the flies is broken. She’s no longer a threat.”

Caw nodded. But somehow he couldn’t quite bring himself to believe it.

The rain had let up by the time they reached the abandoned street where Caw lived. Johnny Fivetails walked by Caw’s side, marvelling at the dark empty houses.

“This place has really gone downhill,” he said. He turned to Caw. “Sorry, man. It’s just a shock.”

“It’s OK,” said Caw. “I like the privacy.”

“The Dark Summer drove people out,” said Crumb pointedly.

“I guess,” said Johnny.

Caw suddenly felt embarrassed as they approached the overgrown front garden and boarded-up house. When Crumb and Pip had moved in a fortnight before, they’d been full of plans to give the place a fresh lick of paint and repair the windows. But fighting the escaped convicts had taken over from all of that.

Caw saw a faint light coming from the dining-room window. The other ferals were already here.

He led the way to the front door, and pushed it open.

Several people were sitting round the dining-room table, and candles were lit across the room. There were familiar faces – like Ali the bee feral, Racklen the wolf talker, and the bat feral Chen – but strangers among them too. In the past couple of weeks, Mrs Strickham the fox feral had been gathering to their cause all the loyal ferals she could find. Some had refused, but most had agreed to join them, reasoning that they were stronger in numbers. Across the floor lay an assortment of dogs, and a few birds and lizards clung to the furniture.

The room was heady with a potent mix of food smells. Some ferals were digging into takeaway cartons, while others had scavenged plates, bowls and any containers they could find from his kitchen.

When Caw had agreed that the good ferals could use his house as a base, he hadn’t realised quite what Mrs Strickham had meant. But it was too late to go back on his word. It made sense to relocate here – their enemies might guess where they were, but at least no innocent people were living nearby. And Mrs Strickham couldn’t volunteer her own house. Caw knew that her husband, Lydia’s father, would never allow the ferals to use his family home for their war councils. Until a couple of weeks ago, the warden of Blackstone Prison hadn’t even known his wife was a feral, and from what Caw could gather, he wasn’t all that happy about it. If it wasn’t for her father, Lydia might be here with them now. She would have found a way to make Caw feel better about all this.

The tall figure of Mrs Strickham strode over to them. She was dressed in dark jeans and brown leather boots, with a pale roll-neck jumper. Her long hair was tied back. “We heard what happened,” she said. “I’m glad you’re all OK.”

“They got away with the money,” said Caw, lowering his eyes.

Mrs Strickham touched his shoulder, and he looked up. “But everyone’s all right?” she asked.

“I think so,” said Caw. “It could have been a lot worse …”

Mrs Strickham’s eyes shifted away then went wide. A smile slowly lit up her face. “Johnny?” she said.

“Vel!” cried Johnny Fivetails.

Mrs Strickham flew past Caw and embraced the coyote feral. Caw had never seen her look so happy. There was a commotion as several others crowded round, taking it in turns to hug Johnny or shake his hand. Even Racklen, who rarely smiled, was beaming.

Caw noticed Crumb was hanging back in the doorway. He didn’t like crowds either. All these people sitting on his furniture made Caw feel like a stranger in his own home. It was becoming hard to breathe in here.

“So what happened?” asked Mrs Strickham, addressing Caw.

He felt the room turn its attention on him. “Lugmann hit Pickwick’s bank,” he said unsteadily. “We tried to stop them, but they had the bison feral.”

“And Mr Silk,” Johnny pitched in. “It was well planned.”

Mrs Strickham nodded grimly. “I suspected the moth feral wasn’t gone for good.”

“Mr Fivetails came to our rescue!” said Pip. “The bison was going to maul me!”

Johnny shrugged modestly. “Thank the coyotes, not me,” he said.

“Our enemies are getting bolder,” said Crumb. “A bison in the city – it wouldn’t even have happened in the Dark Summer.” He lowered his voice. “We think there might be a new boss.”

Velma Strickham’s eyes widened again, and she gestured to the wolf feral. “Racklen, Crumb, Johnny – we need to discuss this properly. Caw, do you want to get some food and join us?”

The room filled with a hubbub as the other ferals began talking with each other and with their animals. A snake wound down the banister and butterflies fluttered around the lampshade. A Great Dane lay sprawled across the sofa, drooling on the carpet. Caw was beginning to feel dizzy.

“I might go outside and get some fresh air first,” he said.

Johnny looked a little surprised. “We could do with your input, Caw,” he said.

A bright parrot flew past Caw’s face and sparks flashed across his vision.

“Back in a minute,” muttered Caw, as his feet carried him towards the back door. He just needed to get away from all the noise. Crumb would say it better than he could anyway. He tripped over a snoozing fox, which bared its teeth at him.

“Stop it, Morag,” said Mrs Strickham. “Sorry, Caw, she’s old and grumpy.”

Caw stumbled into the kitchen, where a couple of lizards eyed him from the counter. Pip caught his arm.

“Hey, Caw, let me show you something,” he said. “I’ve been practising my power.”

“That’s great,” said Caw as the room spun around him. “But can it wait?”

Pip lowered his eyes. “I guess so.”

“Maybe later?” said Caw, feeling guilty as he grasped for the door handle. “I want to see, I promise.”

“OK,” said Pip.

Caw flung open the back door, and gulped in the cool garden air with relief. All those ferals inside needed somewhere to meet, but Caw felt a flash of annoyance at how they had made themselves at home. It was still his house, after all. He wondered if the arrangement was going to be permanent.

You OK? asked Shimmer.

Caw saw her perched on the kitchen windowsill, talons clinging to the edge of a broken plant pot.

“I think so,” he said.

Glum and Screech are up in the nest, said the crow. They got some egg-fried rice. I told them to save you some, but you know Screech …

Caw made his way down the overgrown garden path. It must have been beautiful once – there were still flowers of every description growing among the weeds and the remains of a delicate wooden archway. Caw tried to remember playing here with his mum and dad, but his memory refused to give anything up. A rose bush had grown away from the trellis in a wild sprawl, and he had to pick his way past the thorny overhang.

At the back of the garden grew a tall chestnut tree, covered in knots and whorls. On sunny days, its huge canopy cast the garden in an emerald glow, but now its leaves were slick and dark with raindrops. Caw wedged his foot on a scar in the bark, pushed upwards and leapt for a low-hanging branch. Water droplets scattered from the drooping leaves as he swung up to sit astride it. As Caw scrambled swiftly up the tree, the tension across his temples vanished. Soon he couldn’t hear anything but the leaves rustling as the dense foliage lent everything a peaceful hush.

The nest at the top of the chestnut tree was almost invisible from the ground, and Caw liked it that way. With the help of a legion of crows, he’d moved his tree house, piece by piece, from Blackstone Park. He knew that he had a cosy bed in the main house, but it brought him comfort to have his former home close at hand. He’d even slept out here once or twice, and he had a feeling he’d want to tonight.

As he climbed in, Screech looked up, rice scattering from his beak.

You want some? he said.

“I’m OK, thanks,” Caw said.

Phew, said Screech, head disappearing into the carton again.

Glum opened one eye, peering out in the direction of the house. Bit noisy in there, isn’t it? he said.

“I’m sure it won’t be forever,” said Caw doubtfully. He lay down across the nest, hands behind his head, and stared up at the gently swaying leaves. The only sound was the steady drip-drip of rainwater. It made him think of a book he’d been reading – with a bit of help from Crumb. There was a story in it about an angry god who made it rain until everyone in the world was drowned. Well, almost everyone. One man and his family survived in a great big ship called an ark. Somehow he invited two of every animal on board.

Sounds a bit unlikely, Glum had said when Caw told him about it.

“Maybe he was a feral,” Caw had suggested.

The nest was the perfect place for Caw to empty his thoughts. Sometimes, it wasn’t hard to fool himself that he was back in the park – just Caw and his crows, before his world changed completely. Back then he hadn’t known that there were other ferals in Blackstone. He hadn’t even known there were ferals at all. Life was hard, of course, but it was simple too. Forage, stay out of sight and sleep. No Spinning Man, no Mother of Flies, no fighting against ferals who wanted to kill him. But no friends either – other than his crows, Screech and Glum. And his oldest companion, Milky, who was gone forever to the Land of the Dead. No Lydia. No Mrs Strickham or Crumb or Pip.

No Selina.

Guilty feelings surged through Caw’s brain. Poor Selina. What was going on in her head? Was she dreaming or just drifting on a sea of emptiness?

Caw sat up, rocking the nest slightly. “We need to check on Selina,” he said.

Again? asked Screech.

“There might be a change,” said Caw firmly.

It’s Glum’s turn, said Screech.

I’ll go, said Shimmer.

“Caw, are you up there?” called a familiar voice from below.

For a moment, Caw thought about not answering. He was fairly sure Mrs Strickham couldn’t see him, and she wouldn’t be able to climb up. Nor would her foxes. One of her creatures must have seen him come up – Velma had spies everywhere.

“Caw?” she said again.

“Ladder’s coming down,” he called out. “Stand back.”

He’d found the old rope ladder already attached to the tree, and with a bit of fixing up it was perfect for guests. He unfastened it from the nearby branch and let it unroll.

The ladder tightened and swayed as it took Mrs Strickham’s weight, and a few seconds later her head broke through the foliage. She climbed a little unsteadily, and it was odd to see her so unsure of herself – the fox feral was normally completely in control. Caw offered a hand to help her in. For a brief instant, he remembered the first time he’d met Lydia and smiled. She’d invited herself in too.

Scrambling over the edge, Lydia’s mother regained her composure as she crouched in the tree house. She’d never been up here before.

“Well, this is … um … cosy,” she said.

It’s not built for two, Glum snapped.

Mrs Strickham looked at the old crow askance. “I might not speak crow, but I’m guessing that was a grumble.”

Glum haughtily turned his beak away.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “I’m not staying long.”

As she glanced around the nest, Caw wondered what it was she wanted.

“So, you know Johnny?” he said.

Mrs Strickham smiled and nodded. “Very well,” she said. “He saved my life, on more than one occasion. I never thought he would come back.” She shook her head in wonder. “Anyway, Caw, that’s not what I came to speak with you about. I wanted to thank you for letting the other ferals use your home. A place where we can gather offers us security – a lot of those ferals inside are scared of becoming the next target.”

“It’s fine,” said Caw, sort of meaning it. “But is this really the best place? There isn’t even any electricity. Wouldn’t they be better somewhere … else?”

He knew it sounded like an excuse, but Velma didn’t look annoyed. Instead, a wave of sadness passed over her face.

“I wish they could stay at mine,” she said, “but things at home are … they’re a little difficult. Lydia’s father … let’s just say he’s trying to get his head round some changes.”

Caw tried to look sympathetic – things must be worse than he had imagined at the Strickhams’.

“Don’t worry, though,” said Mrs Strickham with forced brightness. “He and his prison guards are working with the police to track down the escaped convicts. We can win this battle if we all pull together.”

“I know,” said Caw.

“And that’s why,” continued Mrs Strickham, “I wanted to speak with you about the Midnight Stone.”

Caw resisted the urge to look up towards the whorl in the tree trunk a few feet above Mrs Strickham’s head. Hidden inside that whorl, wrapped in a cloth pouch, was the Midnight Stone. Caw had threaded it on to a piece of cord so he could wear it round his neck, but the tree seemed the safest place to keep it out of sight.

So that’s what she’s after, said Glum.

“What about it?” asked Caw.

“It’s a great burden on your shoulders, Caw,” said Mrs Strickham. “If ever you want help, someone else to hold on to it, then—”

“No,” said Caw quickly.

The Midnight Stone had been guarded by his ancestors for hundreds of years – since the days of the greatest crow talker that ever lived, Black Corvus. Caw’s famous ancestor had persuaded other ferals of his time to lend a portion of their powers to the Midnight Stone. This was in order to conserve their lines, in case they were killed without a feral heir. The Midnight Stone could absorb the abilities of any feral who touched its surface and bestow those powers on a normal human.

Caw’s mother had kept the Midnight Stone safe from the Spinning Man, and had been murdered protecting it. The Mother of Flies had used it to create a fearsome army, and Caw had almost died getting it back. The Midnight Stone belongs to the crow line.

“All I’m saying—” began Mrs Strickham.

“I can look after it,” said Caw firmly.

You tell her, said Shimmer.

Mrs Strickham smiled. “I know you can, Caw,” she said, touching his knee. Then she took a deep breath. “I should get back to the others.”

She reached out for the rope ladder and placed a foot on a rung. But once she had climbed down a couple of steps, she stopped.

“One more thing, Caw,” she said.

“Yes?” said Caw.

“Can you talk to Lydia for me? She’s having a tough time. With things at home.”

Caw swallowed. He wanted to help his friend, but he wasn’t sure how. He knew nothing about families or family problems. He hadn’t even known his own parents.

“Just hearing from you would help,” said Mrs Strickham.

“Sure,” said Caw.

“Thank you.”

As the lush leaves swallowed Mrs Strickham, Screech flapped on to Caw’s arm.

What does she want with the Stone? Glum said.

“You heard,” Caw replied. “She wants to look after it.”

Or maybe she wants to use it, said the crow. If there’s going to be another war, she could use the Stone to create her own feral army.

Caw hadn’t thought of that. “No one is going to use the Stone,” he said. “It’s too risky.”

You say that now—

“Glum, can you go and check on Selina, please?” Caw interrupted. He’d had enough of the crow’s chattering.

Me? said the crow. Why me?

It’s your turn, old-timer, said Screech.

I don’t mind going, said Shimmer.

“No. Glum goes,” said Caw. “Please.”

All right, said Glum. But I’m telling you, there won’t be any change.

He spread his wings and dropped out of the nest, gliding gracefully between the leaves.

The other crows were silent, but Caw couldn’t shake the niggling doubts from his mind. Could Glum be right about Mrs Strickham? And if she wanted to use the Midnight Stone, why wouldn’t she come straight out and say it?

Caw’s neck prickled with an uncomfortable sensation of being watched. He scrambled up a branch until he could push the leaves aside and peer at the house. His house, even if it had been commandeered.

There was a flock of parakeets on the guttering under the roof’s edge. The upstairs windows were empty.

Then a flash of orange caught his eye, disappearing behind the chimney stack. He wasn’t sure, but he thought it might have been a fox.

Caw waited a few seconds, then he let the leaves move back to their natural resting place and climbed down to the nest below.

“Come on!” he said, gripping her hand tighter. “We have to run!”

His breath was like fire in his lungs as they skidded round a corner. He didn’t dare look back. He could feel them following – a menacing presence that grew all the time.