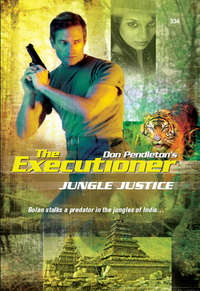

Jungle Justice

“Which means he may start taking other risks, making mistakes. I’d hate to see him fixate on the embassy, its personnel. This guy’s been living like a hermit in the jungle since his prison break. I’m not sure he was civilized before that all went down, but he’s a Grade A wild man now.”

“A wild man with a taste for ivory and tigers,” Bolan said.

“And hostages. Let’s not forget.”

“How solid is his dossier?”

“Good question. The ambassador to India says we got everything they have in New Delhi. Beyond that, who knows?”

“Naraka could have someone running interference for him in the government,” Bolan suggested.

“It’s a possibility, all right.”

“And if I find someone like that? What, then?”

“Officially, we’d want to know about it. Off the record, use your own best judgment.”

“All right,” the warrior said, at last. “Let’s see the files.”

THE FILES HAD BEEN condensed, photos and all printed on flimsy paper for convenience and easy disposal when Bolan had finished his reading. He sat on a bench in the sunshine, outside Fort McHenry, with Brognola at his side, watching any stray tourist who wandered too close. Bolan read steadily, absorbing all the salient facts and asking questions when he needed to.

His contact, Abhaya Takeri, was a twenty-six-year-old ex-soldier who had dabbled in private security before landing a dull office job in Calcutta. That had lasted for nearly a year before he got restless, picking up covert assignments from his government, and later from the CIA. It wasn’t clear in Takeri’s case if one hand knew what the other was doing, but he’d managed to avoid any conflicts so far, after three years of service, and that said something for his tradecraft at the very least.

Takeri’s photos were a study in contrast. The first, a posed shot in his army uniform, revealed a stern young man who wouldn’t smile to save his life, proud of his threads and attitude. The other was a candid shot, taken just as Takeri left a small sidewalk café, his arm around a pretty, laughing young woman. Takeri’s smile seemed genuine, good-humored, as if he enjoyed his life. The flimsy printouts meant that Bolan couldn’t check the flip side of the photographs for dates, but he assumed the army photo had been taken first. Takeri seemed a little older in the second, definitely more at ease.

Takeri’s record in the military had been unremarkable, and most of what he’d done since entering the cloak-and-dagger world was classified. Of course the CIA didn’t mind leaking what he’d done for India, as long as it had no impact on his work for the Company. Apparently, Takeri had been used to infiltrate a labor union thought to be involved in sabotage—they weren’t, according to his last report—and to disrupt a group of Sikhs who showed displeasure with the government by blowing up department stores. Four bombers had been sent to prison in that case, while their ringleader had committed suicide.

It sounded like a good day’s work.

Takeri spoke three languages, had studied martial arts before and after military service, and he’d qualified with standard small arms in the army.

“Sounds all right,” Bolan said, handing the dossier to Brognola.

Balahadra Naraka was something else entirely. Thirty-eight years old and a career criminal by anyone’s definition, he had survived Calcutta as an orphan, living by theft and his wits on the streets, then fell in with poachers when he was a teenager. The shift to country living didn’t help. Naraka was suspected of killing his first game warden at age nineteen, but no charges were filed in that case and he’d remained at large for three more years, then took a fall for shooting tigers. The charge carried a five-year prison sentence, and he’d spent nearly a year in jail prior to trial. Upon conviction, Naraka had received the maximum and was packed off to serve his time.

It took him nearly three years to escape, but he made up for the delay in grisly style. Using a homemade shank, he gutted one guard on the cell block, took another hostage and escaped in one of the prison vehicles. Car and hostage were abandoned on the outskirts of civilization, the guard decapitated, with his head mounted as a hood ornament.

Since then, for nearly twelve years, Balahadra Naraka had been a hunted fugitive, although it barely showed from his lifestyle. Granted, he spent most of his time in tents or tiny jungle villages, but so did half the population of West Bengal. His photos—half a dozen snapped by Naraka’s own men and sent to major newspapers—always depicted him in a defiant pose, armed to the teeth, standing beside the carcasses of tigers, elephants, or men in uniform.

Brognola had been right about the bandit-poacher’s body count. Although it seemed most of his victims were officials—cops, soldiers, game wardens—no two sources ever quite agreed on how many men he’d killed. The lowest figure Bolan saw, in excerpts from assorted press clippings, was 105; the highest, lifted from a sensational tabloid, ascribed “nearly four hundred” slayings to Naraka and his gang.

It was peculiar, Bolan thought, that no official source kept track of government employees murdered by a bandit on the prowl, but numbers didn’t really matter in the last analysis. Naraka was a dangerous opponent, and he’d moved from killing local lawmen to murdering U.S. diplomats.

Bolan assumed the Langley snatch had been a one-time thing, impulsive, maybe even carried out by a subordinate without Naraka’s prior knowledge. It made no difference, though, because Naraka had a lifelong pattern of internalizing and repeating bad behavior. If he’d been apprehended for his first known homicide, it might’ve made a difference. But as it was…

Naraka might be something of a folk hero to rural villagers, who welcomed charity and anyone who helped remove the threat of tigers from their dreary lives, but he still qualified as a mass murderer—perhaps the worst in India since British troops suppressed the thugee cult during the nineteenth century. If Bolan could supply the final chapter to Naraka’s long and cruel career, so much the better.

“He’s a tough one,” Bolan told Brognola. “Knows the ground like Jungle Jim. It won’t be easy to find him, and even then—”

“You’ve tackled worse,” Brognola said.

“Maybe.” Bolan handed back Naraka’s file. “Just let me check the ground.”

It was the worst of both worlds—first, a teeming city, second largest in the country, steeped in grinding poverty, then swamps and jungles rivaling the thickest, least hospitable on Earth. The Sundarbans, where Bolan would be forced to hunt Naraka if he couldn’t catch his target in Calcutta, spanned 2,560 square miles in West Bengal, with more sprawling across the border into Bangladesh. The Indian portion included a 1,550-square-mile game preserve, where three hundred tigers were protected by law, since the early 1970s.

Nor did the Sundarbans consist of any ordinary jungle. Seventy percent of the region lay under salt water, comprising the world’s largest mangrove swamp, crisscrossed by hundreds of creeks and tributaries feeding three large rivers—the Brahmaputra, the Ganges and the Meghna. Access to much of the region was boats only, and if tigers missed a visitor on land, the tourist still had to watch out for sharks and salt-water crocodiles. Electrified dummies had failed to discourage the cats, and every tourist party that entered the Sundarbans traveled with armed guards.

All that, before poachers and bandits were added to the mix.

“Sounds like malaria country,” Bolan said.

“I’ve got a medic on standby to update your shots,” Brognola answered.

“Thoughtful to a fault.”

“That’s me.”

“All right,” the Executioner replied. “I’m in.”

4

Calcutta

The cab dropped Bolan and Takeri two blocks north of Bolan’s hotel and they walked back through the darkness, alert for any sign of followers. Spotting none, they entered the lobby, where the night clerk shot a glance at them, suspicious, then ignored them after recognizing Bolan.

Takeri started toward the creaky elevator, but Bolan stopped him with a word and steered him toward the stairs. If anything had soured since he’d left the place that evening, Bolan didn’t want to meet new adversaries for the first time when the elevator’s door jerked open and the hostiles blazed away at point-blank range.

It proved to be a wasted effort, if security precautions could be wasted in a combat zone. No enemies were waiting for them on the third floor, none in Bolan’s room after he used his key and cleared the threshold in a rush, pistol in hand. The exercise did not make him feel foolish, even so.

Better to be alive and taking too much care than to relax and die.

When they were safely locked inside the room, lights on and curtains drawn, Bolan repeated his original question. “All right, we’re off the streets. Now fill me in on who we’re running from.”

Takeri found a seat and filled it, stretching in an effort to relax. “You understand I cannot be precisely sure. I did not recognize those men.”

“Best guess?”

“It was the first direct attempt upon my life since I left military service. I have enemies, of course, but in the circumstances I assume it was related to your mission.”

“Break it down.”

“Sorry? Oh, yes, I see. In preparation for your coming, I initiated certain contacts. Seeking information on Balahadra Naraka and his associates, attempting to identify his local contacts, vendors and the like. I exercised the utmost caution, but—”

“You tripped some wires, regardless,” Bolan finished for him.

“It is possible,” Takeri answered ruefully. “The other possibility, revenge for some work previously done, strikes me as too coincidental at the present time.”

“Agreed.”

It was a poor beginning to the mission, with his guide and contact compromised, already hunted by the enemy. Bolan had been sucked into the violence, seen by the enemy, and might have sacrificed the critical advantage of surprise.

Or, maybe not.

“You need to lay out everything you’ve done,” he told Takeri. “Everyone you’ve spoken to about Naraka, when and where. If we can figure out who’s hunting you, it tells us which direction we should go to minimize exposure.”

“Certainly.” Takeri frowned. “But, everyone?”

“In order, if you can,” Bolan replied. “We’ve got all night.”

“Do we have coffee?”

Bolan made a call to room service, then settled in to listen while they waited for the coffee to arrive.

“I started with police contacts,” Takeri said. “A Captain Gupta in Calcutta, who collaborates with agents from the Ministry of the Interior to curb the traffic in endangered species and their relics.”

“Is he straight?” Bolan asked.

“Meaning honest?”

“That’s my meaning.”

“I believe so,” Takeri said. “His promotion came through merit, based on his arrests of poachers and their contacts in the export trade. Over the past three years, he has maintained an average of three arrests per week.”

“How many were convicted?” Bolan asked.

Takeri shrugged at that. “I’ve no idea. Is it important that we know?”

“Where I come from,” Bolan replied, “it’s not unusual for crooked cops to make a lot of busywork arrests that go nowhere. They pick up prostitutes and small-time dealers, run them through the system to compile a quota of arrests and bag their commendations, while the courts dish out probation and small fines. Meanwhile, the cops draw paychecks from both sides, and business continues as usual.”

“I see,” Takeri said. “Of course we have such officers in India, as well. But I do not think that Gupta stands among them.”

“Based on what?”

“His reputation. While I’ve told you his promotion came through merit, I should first have mentioned that it had been long delayed, apparently by his refusal to participate in—what is the expression? Office politics?”

Bolan felt better. “Okay, then. What did he give you?”

“Names and addresses of dealers known or thought to traffic in the sort of merchandise Naraka normally supplies. You understand that it is not all tiger pelts and ivory?”

“I got the briefing,” Bolan said. “Weird mumbo-jumbo medicine.”

“To you and I, of course,” Takeri answered. “But to millions in the East, such items are believed to be extremely potent—as their purchasers would hope to be. The so-called medicine concocted from these outlawed items has been used throughout Asia for several thousand years.”

“And no one’s noticed that it isn’t working?” Bolan asked.

“Perhaps it does work, Mr. Cooper, for selected devotees. In the Caribbean and parts of the United States, you have practitioners of voodoo, yes?”

“That’s right.”

“In Africa and parts of South America, cults practice human sacrifice this very day.”

“I wouldn’t rule it out,” Bolan replied.

“Belief,” Takeri said. “It has great power, even though skeptics deny it. When your faith healers perform on television, many people laugh, dismiss it as a fraud, and change the channel, yes? But millions more believe. And who’s to say that none is truly healed?”

“All right,” Bolan said, “let’s assume that eating tiger organs makes some old man happy in the sack. I wasn’t sent to analyze folk medicine or magic. Let’s cut to the chase.”

“I am attempting to explain,” Takeri said, “that some of those with whom Naraka deals are men of faith. They’ll never give him up. I have a list of six or seven names but have not pressed them, knowing it would be a waste of time.”

“Who have you pressed?” Bolan asked.

“I made inquiries with two dealers in Calcutta whom Captain Gupta identified as covert traffickers in tiger pelts and ivory. Posing as a potential buyer, I approached them and was courteously told that while such items sometimes come on offer from the hinterlands, it is illegal to purchase or sell them. The problem, I suspect, lies in the fact that I am native to the area, while nearly all the traffic in such items flows to foreign dealers.”

“So, you struck out with the vendors,” Bolan said.

“Correct.”

“And underneath that courtesy, did either one of them smell like a murderer?”

“In my assessment, no.”

“We’re getting nowhere,” Bolan said.

“I must confess some disappointment in my progress, to that point,” Takeri admitted. “But I did not grow discouraged. If the dealers would not speak to me, I thought, perhaps I could get through to someone else.”

“Such as?”

“Illicit trade of any kind requires protection. Captain Gupta let me have another name.”

“I’m listening,” the Executioner replied.

Takeri studied the American, impressed by his intensity, his bearing and the way he had performed during their skirmish with the assassins on the street. The man who called himself Matt Cooper seemed a worthy ally, and the CIA was paying for Takeri’s services—but it was still a risky business, as had recently been demonstrated by the rude attempt upon his life.

“Girish Vyasa,” he replied after a moment’s hesitation. “He is a customs agent. As you know, cooperation from the Customs Service is essential to the foreign trade in contraband.”

“Of course,” Bolan agreed.

“Girish Vyasa is a man of certain appetites, the cost of which exceed his salary. Perhaps they also make him vulnerable to extortion. Who can say? In any case, Naraka pays him handsomely for letting certain shipments pass without detailed inspection. Others may be paying him, as well.”

“Why is Vyasa still in business if your Captain Gupta knows all this?” Bolan asked.

“It seems that Vyasa in turn is protected by men of influence in Calcutta and New Delhi. Corruption spreads. No government is perfectly immune.”

Nodding, Bolan replied, “I take it you inquired about Vyasa in more detail?”

“Certainly. And therein lies my fault, presumably. He is, as I’ve explained, protected—both officially and unofficially.”

“Someone got wise and put the hunters on your trail.”

“I must assume that is the case,” Takeri said. “If any negligence of mine has jeopardized your mission, I must now apologize.”

“We couldn’t count on cover all the way,” Bolan replied. “I would’ve liked a better lead, but we can work with this.”

Takeri frowned. “But if the hunters, as you put it, are aware of our intentions—”

“Scratch that,” Bolan interrupted. “We’ll assume they’re onto you for asking questions, but they won’t know why, or who you’re working for. They don’t know me at all, beyond a glimpse tonight, and there’s no way they have a handle on my plans.”

“Because?”

“I haven’t made plans, yet.”

Takeri’s frown deepened. “I draw no reassurance from that statement, Mr. Cooper.”

Bolan shrugged. “Don’t sweat it. Coming in, I had no fix on the best way to reach Naraka. Now I’m warming up to it.”

“You have a plan, in fact?”

“It’s coming to me. First, I need to have a word with this Vyasa character.”

“I say again, he is protected.”

“Not from me.”

The cutting edge of Bolan’s tone sent an unexpected chill rippling along Takeri’s spine.

“You would approach him directly?”

“That’s right.”

“And if he’s being watched? Guarded?”

“We’ll have to take that chance.”

Takeri’s frown deepened. “When you say ‘we’—”

“You’ll need to show me where Vyasa lives and point him out. Aside from that, I’ll need details of what your Captain Gupta has on him, what links him to Naraka. Dates, facts, figures. Anything at all to crack him open, make him feel cooperative.”

“I see.” From where Takeri sat, it was a grim vision indeed. “But once again I ask, if he is guarded?”

“We’ll see how it goes,” Bolan replied. “You did okay tonight against those cutters.”

“Still, if you had not arrived just when you did, the outcome may have been a disappointment.”

“We’ll avoid that in the future if we can.”

“If I am permitted to inquire, what are you, Mr. Cooper? Surely not an analyst.”

“I wouldn’t say that. No.”

“What, then?”

“A trouble-shooter,” the American replied. “We’ll let it go at that, if you don’t mind.”

“Of course.”

“About those details on Vyasa—”

“Captain Gupta did not favor me with all specifics of the case, you understand.”

“Just give me what you have.”

“On several occasions—five or six, I think he said—Vyasa has been seen with export dealers linked to the Naraka group. In normal circumstances, these are men Vyasa should have been investigating, possibly arresting, but he seemed to be on cordial terms with all of them. At two meetings, police observed the passage of an envelope into Vyasa’s hands.”

“Containing money?” Bolan asked.

Takeri shrugged. “Sadly, they did not stop him to inquire. There is a mystery of sorts in that respect. His bank accounts—those known to the authorities, at least—show no unusual or unexplained deposits, yet Vyasa lives beyond his means.”

“So, he’s been hiding cash somewhere.”

“Presumably.”

“Maybe we’ll shake some of it loose from him and use it on the next phase of our journey.”

“Which would be?”

“I thought you understood. I’m here to find Naraka.”

“But he almost never leaves the Sundarbans.”

“I guess that’s where we’ll find him, then,” Bolan stated.

Again, the deadly we, Takeri thought. “I should advise you, Mr. Cooper, that my personal experience in fieldwork of this sort is…limited.”

“You spent time in the military, I believe?”

Takeri masked his first rush of surprise. “That’s true.”

“And you’re my guide for the duration, yes?”

“Correct.” Takeri felt the noose settle around his neck.

“No problem, then.”

No problem. The phrase was said as if the words would not only allay Takeri’s fear but turn him into something he was not. A hunting guide, perhaps. A jungle warrior. True, he had been trained for living off the land and fighting in the wilderness, but all of that seemed long ago and far away.

“I will endeavor not to fail you, Mr. Cooper,” he replied.

“It’s Matt. And failure’s not an option.”

“This is all to do with the Americans, I take it? Those Naraka kidnapped?”

“Those he killed. That’s right.”

“If he had not involved your people—”

“Then I likely wouldn’t be here. But he did, I am and we’re together in this thing for better or worse, if you think you can handle it.”

Takeri knew he should resist the challenge, not rise to the bait, but at the moment it seemed irresistible. “I can. I will.”

“Good man. Now, what say you go on and bring me up to speed about Vyasa. I’d like to drop in for a visit tonight, and before we do that I need chapter and verse.”

Takeri had a sense that everything was happening too rapidly, that he was being swept away, but what choice did he have? His working contract with the CIA demanded full cooperation, and he’d gone so far already in the matter that his life was placed in jeopardy. Those who had tried to kill him would already have his home staked out. At least, with the American, he had a better fighting chance.

But the Sundarbans!

“All right,” Takeri said at last.

5

As they discussed their short-range plans, the Executioner took stock of Abhaya Takeri, comparing his reticence to the forceful response he’d witnessed from Takeri in the street a short time earlier.

The change was only natural, of course. When Bolan met the Indian, Takeri had been fighting for his life, with no time to reflect on the advisability of any certain move. A kill-or-be-killed situation always tested humans to the limit. Those who passed the test survived, while those who failed were meat for the machine.

During the street assault, Takeri’s military training and survival instincts had emerged to save him, with some timely help from Bolan. Whether he would have survived alone was something else, a question left unanswered for all time, but it was clear to Bolan that Takeri had the courage, strength and will to fight if motivated properly.

Sitting in the relative security of Bolan’s hotel room, Takeri had a chance to think about what he was getting into, weigh the odds against him, letting worms of doubt nibble at his resolve. He wasn’t balking yet, but Bolan knew it could happen.

Strong men could defeat themselves before a contest started by exaggerating the prospective difficulties in their minds. Some heroes, Bolan realized, were simply men who had no time to stop and think.

What soldier started his day with plans to fall on top of a grenade? Or charge the muzzle-blast of an emplaced machine gun, armed with nothing but a satchel charge? Who got up in the morning, thinking, Man, I’d love to die today?

Bolan recognized Takeri’s hesitancy and sympathized with it, but he couldn’t afford an ally who balked when the going got tough. A guide was no use if he brought up the rear.

Bolan went briskly through the plan, watching Takeri sketch a floor plan of Girish Vyasa’s large apartment house. The layout of his living space would be a mystery until they crossed the threshold, but Takeri had spotted exits, elevators, where the doorman stood, which entrances were normally unwatched.

“You’ve thought this through,” Bolan observed.

“I guessed it might be necessary to approach him,” Takeri said, “but I had no plans to go inside myself.”

“Plans change. Go with the flow.”

The smile was thin. “I’ll do my best.”

“He doesn’t have security? No bodyguards?”

Takeri shook his head. “Nothing like that. Vyasa is—or claims to be—simply a public servant. Who would wish to harm him?”

“Good,” Bolan replied. “That makes it easier.”

He spread a large map of Calcutta on the bed, smoothing its creases with his hand, and said, “Let’s plot the route and find at least one alternative in case we have to bail.”