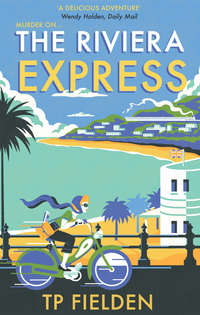

The Riviera Express

Pithers threw his money around (‘noted for his extraordinary generosity’, typed Miss Dimont pertly) and lorded it down at the golf club (‘a sporting enthusiast’). After a lucrative week’s work rendering fat, he would sit in the bar dishing out drink and opinion in equal measure to a befoozled audience made up of the thirsty, the hard-up, the deaf and the occasional owner of a rhinoceros skin.

‘An enthusiastic conversationalist,’ tapped Miss Dimont, who had bumped into the ancient Pithers when the Ladies’ Inner Wheel invited her to their annual nine-hole tournament dinner, ‘he often encouraged others into lively debate.’ Indeed so; that night the lard-like entrepreneur had treated his audience to a twenty-minute peroration on how Herr Hitler was a much misunderstood man; it led, regrettably, to fisticuffs.

‘Indeed his love of life’ (barmaids) ‘and the Turf’ (he rarely paid his bookies) ‘set him aside in the community’ (he had no friends) ‘and will make him a much-missed figure’ (three people went to his funeral, all of them to make sure he was dead).

Weaving such barbed encomiums was Miss Dimont’s consolation, for through the office window she could see across the red rooftops to the promenade, the beach and the glorious turquoise sea, which this morning was like glass. Young lovers strolled hand-in-hand, children built their dreams in the sand, the Temple Silver Band parped joyfully in the Victorian bandstand.

Miss Dimont sighed and picked up another green wedding form.

‘It was love at first sight in the Palm Court of the Grand,’ she rattled. ‘Waiter Peter Potts and cleaner Avril Smedley met under a glittering chandelier and . . .’

This was an inspired introduction to the lives of two very nice but humdrum Temple Regents employed by the town’s grandest hotel. The rest of her report – the guipure lace, the bouquet of white roses, stephanotis and lily of the valley, the honeymoon spent at a secret location – was standard pie-filling, but Miss Dimont adorned the crust with a little more care because she happened to know Peter. She was often in the Grand on business, and he was always most attentive. She was happy that he had found love with Avril for he was rather a sad boy. She would insist that their picture was not added to the Thank Heavens! board, but in truth it was a prime contender.

Her reports had only to be one hundred and fifty words long – on an average Saturday morning she would get through three or four – but she found it difficult to concentrate. Part of her longed to be set free from her desk so she could enjoy the glorious weather this lazy Indian summer was so generously providing, but another part kept returning to the deaths of Gerald Hennessy and Arthur Shrimsley.

The coroner’s clerk had confirmed to Betty that one of the inquests might be troublesome because of certain suspicious circumstances, but refused to add a name or further clues. She would have to wait till Monday at 2 p.m., when proceedings would be opened and adjourned.

If it was suspicious it had to be Shrimsley, Miss Dimont decided, because of the note in his hand. But then again, as she thought about it, that of itself wouldn’t be suspicious if indeed he’d gone against character and done away with himself – a suicide is a suicide. Where was the ‘foul play’ which Rudyard Rhys had hissed at her last night?

It must therefore be Hennessy. She had definitely felt a frisson of fear when she saw that ‘M . . . U . . . R . . .’ traced in the carriage dust, but distance lends clarity and it was quite clear that with no sign of violence or personal distress Hennessy could have suffered no foul play – and though she was no expert, it did indeed look like a heart attack.

It left her nowhere.

Her morning’s work done, she covered up the Quiet-Riter and gathered up the delectable bunch of asters Mrs Reedy had left at the front desk as a thank you for her glowing report on the Mothers’ Union all-female production of Julius Caesar. It had taken a quite extraordinary suspension of disbelief to see this crinkle-permed bunch of ancients, clad in togas and brandishing knives, posing a serious threat to ancient Rome’s democracy, but Miss Dimont had pulled it off magnificently, and here was her reward.

Such was the exchange of kindnesses in Temple Regis. It made it such a wonderful place to live.

Her ride home on the redoubtable Herbert took her along the kind of route that film directors dream about and scour the world trying to locate. But here it was, the coast road out of Temple Regis back to her cottage three miles distant, where the road gently rose to where you could see right across Nelson’s Bay out into the English Channel. Out there, the faded blue of the sea met the white-blue of the sky at some point of infinity which, no matter how hard you tried, you could not pinpoint. The seascape was massive, blinding in its brilliance, making you feel that no other place on earth could touch it. Below, the ribbon of white beach skirted the waves modestly before turning into a sandbar dividing the sea from a freshwater lake which was home to a thousand contented species, winter and summer.

This was England’s Riviera in its simple, unadulterated glory. Miss Dimont had been to Nice and to Cannes, but the Grande Corniche, which hemmed that southernmost part of France, was not a patch on the Temple Road – for here were no unsightly developments of blocks of flats and concrete villas vying with each other for a sight of the sea; instead just an open road with the occasional house on the headland to remind the traveller he was not quite in Paradise.

The thin ribbon of tarmac rounded a bend and made a steep descent to sea level, and as she urged Herbert ever onwards, the spume which rose from the rocks cooled her brow and moistened her lips with its salty zest. Her corkscrew hair bobbed in the wind and Miss Dimont was in seventh heaven.

These moments, of course, are fleeting, evanescent. Life’s realities return all too soon and on arriving home she discovered a note from her neighbour Mrs Alcock complaining about Mulligatawny leaving his collection of mouse entrails on her doorstep. Again!

She unlocked her door, gazed fleetingly at the handsome face staring back at her from the silver frame on the mantelpiece, and made herself a cup of tea.

*

A weekend is what you make it, thought Miss Dimont, as she let herself into the Express offices on Monday morning. Domestic chores need not rule the roost – let there be music!

And so there was – the long-awaited visit from the Trebyddch Male Voice Choir to the village hall on Saturday night was a triumph, with their exquisite harmonies in ‘All in the April Evening’ bringing her to the verge of tears. Then the men pulled off their ties, brought out some guitars and a washboard, and sang some noisy skiffle songs to which she danced giddily.

At the reception afterwards – beer for the men, ginger beer for Miss D – she found that miners from the Valleys could be wonderfully charming. Muscular, handsome, incredibly dark, there was one who . . . but no! She moved her thoughts swiftly on to Sunday matins at St Margaret’s – 003 in Hymns Ancient & Modern, ‘Awake My Soul and With the Sun’.

But now back in the office, the sour smell from the back copies of the newspaper piled on the windowsill behind assailed her nostrils and reminded her that the weekend was over. It was time to go out and make The Calls.

Which was good, for Miss Dimont had been doing some thinking.

What, she asked herself, had happened to Gerald Hennessy’s wife, the glorious Prudence Aubrey? Almost as famous as Gerald, she had starred in a string of black-and-white classics opposite her husband in the early fifties. Her style was about as sophisticated as it comes – sharply pulled-back hair, Norman Hartnell dresses, muted but expensive jewellery, perfect maquillage – and with that slightly sharp delivery which told you this was not a woman to stand any nonsense.

Less had been seen of Prudence on the silver screen of late, but that was probably because she was at home keeping Gerald’s slippers warm, or translating Russian verse into French (her hobby, if you believed the publicity handouts).

Miss Dimont entered the battered portals of Temple Regis police station, a rugged edifice in local red stone as stout and dependable as the town’s constabulary itself. Its interior, however, was another matter – dull paintwork, no carpets, dust and carbolic, and an air of barely controlled confusion. Her regular Monday morning colloquy with Sergeant Gull was now in session.

‘The inquests, Sergeant.’

‘Yes, Miss Dimont?’ The sergeant took out his tobacco-pouch and stared at it doubtfully.

‘Which is the suspicious one?’

‘Couldn’t say, nobody tells me nothing.’

It was always like this. It took ten very irritating minutes to warm the sergeant up before you could get anything out of him, even a cup of tea.

Miss Dimont changed tack.

‘Strange, isn’t it, that Mrs Hennessy hasn’t come down?’

A rapt smile swept slowly over the sergeant’s face. Here, clearly, was a fan of Prudence Aubrey. Was it Shadows of the Night which had enslaved him, or No, Darling, No!, possibly even her Emmelina Pankhurst?

‘She be down this morning,’ he said dreamily, as though already employed by her team of press spokesmen. ‘Riviera Express. The 11.30.’

That would do – she and Terry would be there! The arrival of a film star on the Riviera Express was news, whether they were dead or alive, and this would be a useful follow-up story.

‘Now, Sergeant, on to Mr Shrimsley. Was there a Mrs Shrimsley?’

A wintry smile. ‘That’s a joke, miss, iznit?’

‘Come along, Sergeant, I’m late as it is.’

The sergeant clammed up – either he didn’t know, or wasn’t saying. Always the same with the self-important Gull, and on such a small point too. His answer meant more time having to be spent tracking down relatives.

There seemed no more to be said. The reporter took herself off to the council offices to see what crumbs of information might be gleaned from the forthcoming week’s proceedings, en route taking in the large public notice-board outside the Corn Exchange. This unassuming block of wood had proved a goldmine of stories over the years, a virtual town crier of tales in fact – from lost cats to appeals for assistance; from the emergence of new religious gatherings (they never lasted long) to announcements of the arrival of the latest phenomenon, beat groups. The town prided itself on staying au courant.

Miss Dim herself was much taken by beat groups. Temple Regis had already been visited by Max Bygraves and Pearl Carr and Teddy Johnson, but though there were whispers that Tommy Steele might make a surprise visit, the best they had had of this new music was Yankee Fonzie, just back from a barnstorming tour of France where there had been riots – though having watched his act at the Corn Exchange, Miss Dimont could not be sure quite why the French had gone so mad. Maybe it was his bubble-car; it certainly wasn’t his hairdo.

*

The Calls completed, she retraced her steps to the office but as she approached the police station out popped Sergeant Gull.

‘There you are,’ he said. ‘Got news fer you.’

‘Oh?’ said Miss Dimont. This was unprecedented.

‘Hennessy.’

‘Yes?’

‘’E were going to do a summer season. ’Ere, Temple Regis. Think of that!’

Miss Dimont asked Gull to repeat himself.

‘Oh yers,’ said Gull, as if he had discovered a nugget of gold.

‘At the Pavilion?’

‘Where else?’ said the Sergeant smugly.

Miss Dimont adjusted her spectacles and stared Gull in the eye. ‘How do you know?’ she grilled. ‘How could you possibly know that?’

She turned up the heat because it was the only way with Gull. On the rare occasions he had something worth telling, the policeman invariably prevaricated, wandered round the houses, kept the best wine till last. She hadn’t got time this morning.

‘Come on, Sergeant!’

Gull enjoyed this game of cat-and-mouse but was eager to demonstrate his superior knowledge. ‘Card in Hennessy’s pocket,’ he declared proudly. ‘From Mr Cattermole.’

Raymond Cattermole ran the Pavilion Theatre, an old actor-manager out to grass but clinging to past glories.

‘Most unlikely,’ said Miss Dimont firmly and stepped off towards her office.

‘Card in his pocket,’ called Gull as she rounded the corner.

Miss D swung round. ‘What did it say?’ she demanded crisply.

‘Not much. Something about “looking forward to seeing you then”,’ said Gull.

‘Doesn’t prove a thing,’ snapped the reporter, setting off again for the office. But, as she walked, she chewed over the possibility.

Or impossibility – for Gull’s assertion made no sense. Gerald Hennessy was at the height of his fame as a screen actor – successful, admired, his career as a nation’s favourite well established. Why would he want to spend six weeks in Temple Regis at the Pavilion, where turgid production after turgid production made successive generations of holidaymaker swear they’d never set foot in the place again?

Indeed the perpetrator of these epic failures, Ray Cattermole himself, loved starring in them – so what place would there have been for Gerald Hennessy? Was Cattermole thinking of retiring? Maybe planning a sabbatical next year? (Oh, please, thought Miss Dimont, whose duty it was each summer to review Ray’s dreary fare.)

But no – he’d already informed her in lordly tones of next year’s offerings: Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, and a stage show starring Alma Cogan. There would be no male lead next year for Gerald Hennessy to play.

Unless, of course, Cattermole had been lying – as he often did. Miss Dimont had doubted from the outset whether Temple Regents, while undeniably welcoming, could secure a star of Alma’s lustre to spend six weeks among them any more than they could expect Gerald Hennessy ever to give them his King Lear.

No, there was something odd about the whole thing – what with no leading part for Cattermole, a too ambitious playbill, and the very idea Gerald Hennessy would think of treading the Pavilion’s creaky boards. It must be something else.

But what? Without realising it, Miss Dimont was rapidly coming to the conclusion that if there had been foul play in Temple Regis’s two celebrated deaths it must be to do with the actor, not the detestable Shrimsley.

Back in the office there was a rare daytime sighting of Athene Madrigale. ‘Busy, dear?’ she asked Miss Dimont indulgently.

‘Well yes,’ came the reply. ‘What are you doing here, though? This isn’t your time of day, Athene. It’s Monday morning – you’re a creature of the night!’

‘I felt moved, dear. The spirit awakened within, and I knew I had to give my all to the stars this morning.

‘Also,’ she added, as if imparting a great secret, ‘I needed to do some shopping.’

Athene made the tea while Miss Dimont found Terry to tell him about the impending arrival of Prudence Aubrey. As her cup cooled, reporter consulted astrologer.

‘So you see, Gerald Hennessy – Raymond Cattermole – Alma Cogan,’ she summed up neatly.

‘Yes, I do see,’ said Athene. She paused. ‘Did you know that Gerald and Mr Cattermole were both in a West End play together? Before the War?’

‘How interesting.’ It wasn’t particularly, actors being actors, but the tea wasn’t cool enough to drink yet.

‘Yes, The Importance of Being Earnest. I saw it myself, at the Globe Theatre – Edith Evans, oh! And Margaret Rutherford too!

‘What was interesting is that Raymond was playing Jack, and Gerald, Algernon, then after the first few performances they were switched round so Gerald took the lead part. And wonderful he was! I never cared for that Raymond Cattermole,’ added Athene.

‘So they both had to learn another part?’

‘Yes, and I remember an interview Mr Cattermole gave which said some quite unkind things about Gerald. Quite unusual in those days – created something of a stir. I mean, people in the theatre just don’t talk like that, do they, saying nasty things?’

‘So,’ said Miss Dimont, sipping her tea slowly, ‘you might say there was no love lost between them?’

‘Well,’ said Athene brightly, ‘everyone forgives and forgets. Don’t they!’ And with that she picked up her shopping bag and faded gently, a riot of colours, out of sight.

At last Miss Dimont felt she was getting somewhere. Once upon a time Hennessy and Cattermole were on an equal footing, co-stars in a West End production. Nearly twenty years later Gerald was a star and Raymond was . . . well, it still was something to be an actor-manager of a theatre, and Temple Regis was indeed the prettiest town in Devon, so he was very fortunate. But . . .

But, thought Miss Dimont, beneath the artificial bonhomie she had long ago spied an unhappy and, one might almost say, a tortured soul.

Why on earth had Raymond Cattermole lured Gerald Hennessy down to Temple Regis?

What did he have in mind?

SIX

It had taken Prudence Aubrey more than three days to arrive in Temple Regis to claim the mortal remains of her husband, one of the most famous men in the land. Clearly this was an actress who needed time to prepare for her big entrance.

At 11.30 precisely the Riviera Express pulled into Temple Regis station. As the flood of disembarking passengers ebbed away, Miss Aubrey, swathed dramatically in black, stepped elegantly from the Pullman carriage and paused on the step as if waiting for a barrage of flash guns to pop off.

There was only Terry.

It did not take much persuasion to halt her forward progress, however. Miss Dimont had her notebook at the ready, Terry his camera; Miss Aubrey repaired to the first-class waiting room in a mute acceptance that this was her lot in life, to be harried by the press. The fact that Miss Dimont had done no more than raise her eyebrows, and Terry check his lens, would not in the normal scheme of things rate as press harassment, but you have to be a celebrity to understand just how cruel newspaper people could be.

Miss Aubrey gathered her widow’s weeds around her and sat delicately on a hard oak settle. In deference to her new-found and sadly tragic status, Miss Dimont and Terry remained standing.

‘I’m so sorry,’ began the reporter but got no further.

‘It is a complete tragedy. An actor in his prime, one so adored by the nation,’ rattled out Miss Aubrey, ‘so much loved by his friends and . . .’ dramatic pause ‘. . . family. It is a great loss to the profession and the country.’

She reached into her bag for a small perfumed handkerchief and dabbed her nose, though not so much as to dislodge its maquillage. Her photograph had not yet been taken.

‘I wonder if I could just—’

‘He was telling me only last week how he loved my Emmelina Pankhurst. He said it is the one film he would have paid a large sum to have a part in, just to play alongside me. But, of course,’ she went on, ‘there was no role for Gerald in a film like that.’ Just a sprinkling of contempt garnished her voice now. ‘He took the populist path. And. Who. Can. Blame. Him.’

What rot, thought Miss Dimont. Gerald Hennessy was one of those actors who could do comedy, adventure, war – he even played Shelley once – while Miss Aubrey’s palette was scattered with fewer, paler colours, her most successful films the ones where she dressed magnificently and said little. It really was quite remarkable how universally adored she had become, given everything.

Perhaps Miss Dimont was a little jealous of Prudence Aubrey’s happy marriage to Gerald; perhaps she just preferred not to interview actresses. Perhaps, being a woman of a certain background, it was both – for an actress’s lines, when scribbled in a notebook, always seem so weighty and rich with promise, but when you come to transcribe them, they seem so remarkably devoid of interest.

So far the interview had been about Miss Aubrey.

‘Perhaps then he—’

‘We were to make another film together,’ this elegant steamroller continued, her voice sliding down an octave, ‘our pet project. An English version of The Magnificent Ambersons, only set here, of course. In England.’ Her eyes for the first time focused upon the vaguely dishevelled middle-aged woman before her, clad in a macintosh tied tightly at the waist, with sensible shoes and a silk scarf at her neck – a combination which, if Miss Aubrey had chosen it, would have been carried off with considerable élan. On Miss Dim it all looked a bit haphazard. Maybe Miss Aubrey took her for an idiot.

‘That must have been a—’

‘Of course, we hadn’t signed the contract. I had been waiting for the right director. I was to be the Duchess of Tintagel, Gerald the Duke naturally. It was a broader part for me, requiring many changes of costumes and, of course, the locations . . . stunning houses. Beautiful. Despite the War . . .’

‘May I ask when you last saw Mr Hennessy?’

‘What?’ snapped the actress. ‘What do you mean?’ Suddenly her face was transfigured by a range of emotions considerably more extensive than her fans were generally granted onscreen.

‘I meant . . .’ started Miss Dimont, but then faltered. Her question appeared to have vaulted the actress from a cool if stagey presence into something more closely resembling a cornered animal.

She tried again. ‘I’m sorry if I—

‘Don’t. Just don’t.’

Suddenly the conversation was dangerously electric, and Miss Dimont drew back. Self-obsessed Prudence Aubrey may be, but she was also newly bereaved – and the Riviera Express had its standards of conduct towards its interviewees.

The interview concluded quite rapidly thereafter and Miss Aubrey was wafted away to the Grand by a uniformed chauffeur who materialised out of nowhere – as they always do in Temple Regis when film stars sail over the horizon. It was not a town, after all, peopled entirely by hayseeds.

Terry got his photos. You had to give Miss Aubrey that, she knew how to pose even in a railway waiting room. Somehow widow’s weeds had never seemed more Parisian, more desirable. Cecil Beaton was said to have fallen in love with her, which seemed remarkable to those who knew Cecil, and here she was – in Temple Regis! She was front-page material wherever she went – it was just that she now seemed to be famous for being famous, for, alas, her millions of fans had been waiting a long time for her next film.

Terry drove Miss Dimont back to the office in the Minor.

‘Did you notice how she suddenly turned – just like that?’ said an unsettled Miss Dimont to Terry.

‘Fabulous coat she ’ad,’ said Terry, ignoring the question as usual. ‘Did you see that twirl I got her to do? Talk about New Look all over again! The way that fabric just floated in the air!’

‘A disgrace,’ snorted Miss Dim. ‘Twirling? They haven’t even had the post-mortem on her husband yet, let alone the inquest!’

‘No disrespect,’ said Terry, scratching his head. But the whole encounter – its timing, its focus, and the unexpected bolt of lightning which concluded it – troubled the reporter.

It was lunchtime. Peter Pomeroy, the chief sub-editor, was jerkily dipping his head towards his desk like a heron stabbing at a fish. Seen from a distance this behaviour might seem odd to the newcomer, alarming even, but it was Pomeroy’s way and nobody said anything. After you’d worked at the Riviera Express for a few weeks you came to realise that everyone had their quirks – after all, Miss Dim and Herbert, just think of that! – and if he wanted to pretend he wasn’t eating sandwiches concealed in his desk drawer then who was anyone to say otherwise?

Miss Dim took an apple from her raffia bag and placed it next to her Quiet-Riter. ‘Exclusive,’ she rattled. ‘Riviera Express talks to Gerald Hennessy’s widow, Prudence Aubrey.’ (Exclusive because no other paper thought to turn up, a cause of intense dissatisfaction to the nation’s newest widow.)