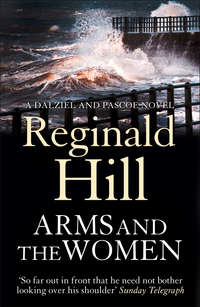

Arms and the Women

REGINALD HILL

ARMS AND THE WOMEN

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2000

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2000

Extract from ‘Marina’ from the Collected Poems 1909–62 by T.S. Eliot (published by Faber and Faber Ltd) Reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

Lines from ‘Girls’ by Stevie Smith from The Collected Poems of Stevie Smith (Penguin) © James McGibbon 1975

Extracts from The Englishman’s Flora by Geoffrey Grigson (Phoenix House 1987)

Extract from A Celtic Miscellany by Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson (Penguin 1971)

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007313181

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007378548

Version: 2015-06-18

Dedication

This one’s for

those Six Proud Walkers

in whose company the sun always shines bright

Emmelien

Jane

Liz

Margaret

Mary

Teresa

who most Fridays of the year…on distant hills

Gliding apace, with shadows in their train,

Might, with small help from fancy, be transformed

Into fleet Oreads sporting visibly…

and, of course, laughing and talking and eating

almond slices,

with fondest greetings from

one of the trailing shadows!

Epigraph

What song the Syrens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, though puzzling Questions, are not beyond all conjecture.

SIR THOMAS BROWNE: Urn Burial

With my own eyes I’ve seen the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a pot, and when the young lads asked her, what do you want for yourself, Sibyl? she replied, I want to die.

PETRONIUS: The Satyricon

Girls! although I am a woman

I always try to appear human

STEVIE SMITH: Girls!

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

PROLEGOMENA

BOOK ONE

i spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

ii who’s that knocking at my door?

iii memories are made of this

iv spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

v revenge and retribution

vi citizen’s arrest

vii a pint of guinness

viii spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

ix bag lady on a bike

x spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

xi a game of hearts

xii doppelgänger

xiii the death of Marat

xiv a man’s best friend

xv spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

xvi oats for St Uncumber

xvii the juice of strawberries

xviii the flowers that bloom in the spring, tra-la!

xix pooh on the patio

xx the last of the cobblers

BOOK TWO

i strange encounter

ii drudgery divine

iii the pavilion by the sea

iv spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

v realms of gold

vi cheated by Protestants

vii the sirens’ song

viii we galloped all three

ix coitus interruptus

x belly or bollocks

xi spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

xii come to dust

xiii faery lands forlorn

xiv a face from the past

xv bloody glass

xvi a palomino pony

xvii a formal complaint

xviii the US cavalry

xix I shall wound every man

xx liberata liberata

xxi an elfin storm

xxii spelt from Sibyl’s leaves

EPILEGOMENA

Keep Reading

About the Author

By Reginald Hill

About the Publisher

PROLEGOMENA

When I go to see my father, he doesn’t know me.

He’s away somewhere else in a strange land.

I tell myself it’s not all bad. He missed all that suffering when we thought Rosie was going to die. And all those refugees in Africa, and in Europe too, that we see streaming across our television screens, he doesn’t have to worry about them. Global warming, AIDS, the Euro, none of these impinges on his consciousness. He doesn’t even have to feel anxious about his roses when gales are forecast in July.

He sits here in the Home, like ignorance on a monument, smiling at nothing.

At least he’s content, the nurses tell us, and we tell them back, yes, at least he’s content.

Content to be nobody and nowhere.

But I have seen him outside of this room, this cocoon, with memories of somebody and somewhere still intermittent in his mind, staring in bewilderment at the woman who is both his wife and a complete stranger, pausing in the hallway of his own house, unable to recall if he’s heading for the kitchen or the garden and ignorant of which door to use if he does remember, crying out in terror as the dog which has been his most obedient servant for nearly ten years comes bounding towards him, barking its love.

Seeing him like this was bad.

But worse was waking in the night during and after Rosie’s illness, wondering if perhaps what we call Alzheimer’s – that condition in which the world becomes a vortex of fragments, a video loop of disconnected scenes, an absurdist drama full of actors pretending to be old friends and relations – wondering whether perhaps this is not a disease at all but merely a relaxing of some psychological censor which the self imposes to enable us to exist in a totally irrational universe.

Which would mean that dad and all the others are at last seeing things as they really are.

Unvirtual reality.

A sea of troubles.

Confused.

Inconsequential.

Fragments shored against a ruin.

Oh, Mistress Pascoe,

Laud we the gods, and let our crooked smokes climb to their nostrils for glad tidings do I bring and lucky joys. No more I fear the heat of the sun, as time which all these years has wasted me now sets me free, most happy news of price, but not for all, for does not time’s whirligig bring in revenges? Thou’rt much in my mind, nor shall I be content till I have seen thy face, when my full eyes shall witness bear to what my full heart feels. May my tears that fall prove holy water on thee! I must be brief, for though my enemies set me free, in freedom lies more danger than in prison, for here through thee and thine the world knows me in their care, but once enlarged, then am I at the mock of all disastrous chances and dangerous accidents by flood and field, with their hands whiter than the paper my obits are writ on and so must wear a mind dark as my fortune or my name. Fate leads me to your side but gives no date, for I must journey now by by-paths and indirect crook’d ways, but sometime sure, when you have quite forgot to look for me, a door shall open, and there shall I be, though you may know me not, but never fear, before I’m done you’ll know me through and through. Till then rest happy while I remain, though brown as earth, as bright unto my vows as faith can raise me.

Close by the margin of a lonely lake, shag-capped by pines that speared a lowering sky from which oozed light unclean whose lurid touch seemed rather to infect than luminate, a deep cave yawned.

Here four men laboured with shovels, their faces wrapped with scarves, not for disguise but as barrier against the stench of the decaying bat droppings they disturbed, while high above them a sea of leathery bodies rippled and whispered uneasily as the sound of digging and the glow of bull-lamps drifted up to the natural vault.

Outside two more men waited silently by a truck which looked almost too broad to have navigated the rutted track curving away like a railway tunnel into the crowding trees. Several yards away on a rocky ledge jutting out over the unmoving, unreflecting waters stood a dusty jeep.

Away to the east, dawn’s rosy fingers were already pulling aside the mists which shrouded the sleeping land, but here the exhalations of the lake still hung grey and heavy over the waters, the vehicle, and the waiting men.

At last from the cave’s black mouth two figures emerged, labouring under the weight of a long metal box they carried between them.

They set it down on the ground behind the truck. One of the waiting men, his thinning yellow hair clinging to his brow like straw to a milkmaid’s buttocks, stooped to unlock the container. Glancing up at the other man from black and bulging eyes, he paused like a vampiricide about to open a coffin, then flung back the lid.

The other man, slim and dark with a narrow moustache, looked down at the oiled and gleaming tubes of metal for a moment, then nodded. The first man snapped his fingers and the diggers closed the box and lifted it onto the back of the truck. Then they returned to the cave, passing en route their two companions staggering out with a second box.

Many times was this journey made, and while the labourers laboured, the watchers went round to the front of the truck and the slim man opened the passenger door, reached inside and picked up a large square leather case which he set on the seat and opened.

The straw-haired, bulging-eyed man produced a flattened cylinder of ivory and pressed a stud to release a long, slightly curved blade. Delicately he nicked two of the plastic containers which packed the case, licked his index finger, inserted it into the first incision, tasted the powder which clung to his damp flesh, repeated the process with the second, and nodded his accord.

The dark man closed the case then took the other’s outstretched hand.

‘Nice to do business,’ said bulging eyes. ‘My best to young Kansas.’

The other looked puzzled for a moment then smiled. The older man too had a speculative look on his face as he held onto the other’s hand rather longer than necessary. Then he too smiled and shook his head as though to dislodge a misplaced thought, let go and took the grip to the jeep where he laid it on the back seat.

By now the loading of the truck was complete and the four diggers stretched their aching limbs in the mouth of the cave and unwound their protecting scarves. Two were ruddy-faced with their exertions, the other two flushed dark beneath their sallow skins.

The first pair went towards the jeep while the second pair joined the slim man who was securing the tailgate of the truck.

These two looked at each other, exchanged a brief eye signal, then reached for the holsters beneath their arms, drew out automatic pistols, and moved towards the jeep, firing as they walked. The two ruddy-faced diggers took the bullets in their backs and pitched forward on their faces while ahead of them the straw-haired man fell backwards, his eyes popping even further in astonishment under the fillet of blood which wrapped itself around his brow.

One of the gunmen continued to the jeep and leaned into it to retrieve the grip. His companion meanwhile turned back to the truck where the slim man was standing as if paralysed.

‘Chiquillo!’ he called. ‘Recuerdo de Jorge. Adiós!’ And let go a long burst.

The slim man felt a whip of hot pain along his ribcage which sent him spinning like a top behind the truck. The rest of the burst went straight through the mouth of the cave where the bullets ricocheted around the granite walls and up into the high vault, triggering first a rustling ripple, then a squeaking, wing-beating eruption of bats.

The gunman paused, looking up in wonderment as the bats skeined out of their rocky roost and smudged the dark air overhead. So many. Who would have thought there would be so many?

Then as they vanished among the trees he resumed his advance.

But the pause had been long enough for the slim man to reach under the truck and drag down the weapon taped beneath the wheel arch.

He shot the gunman through the leg as he passed by the truck’s rear wheel, then through the head as he crashed to the ground.

The second gunman dropped the grip and crouched low with his weapon aimed towards his dying companion.

But the slim man came rolling out of the other side of the truck, and gave himself time to take aim and make sure his first shot found its target.

The second gunman held his crouching position for a moment, then toppled slowly sideways and lay there, gently twitching, his visible eye fixed on the trees’ high vault. The slim man approached carefully, one arm wrapped round his bleeding side, and emptied the clip into the watching eye.

Then he sat down on the grip and pulled open his shirt to examine his wound.

It was more painful than life-threatening, flesh laid bare, a rib nicked perhaps, no deeper penetration. But blood was pouring out and by the time he’d bound it up with strips of shirt torn from the dead gunman at his feet, he’d lost a lot of blood.

He opened the grip, took out one of the packets the pop-eyed man had nicked, poured some of the powder into his hand, raised it to his nose and took a long hard sniff.

Then he took out a mobile phone and dialled.

‘Soy yo… si… I did not think so soon… si… poco… not so wide as a barn door… the CP… it has to be… I am sorry… dos horas… quizá tres… si… at the CP… si, bueno… te quiero… adiós.’

He put the phone away and picked up the grip, wincing with pain. As he moved away, he thought he sensed a movement from the vicinity of the jeep and turned with his gun waving menacingly.

All was still. He hadn’t the strength for closer investigation. And in any case, his gun was empty.

He resumed his progress to the truck.

Getting the grip into the driver’s cab and himself after it was an agony. He sat there for a while, leaning against the wheel. Did something move by the jeep or was it his pain giving false life to this deadly tableau? Certainly in the air above, the bats, reassured by the return of stillness, were flitting back into the mouth of the cave.

He dipped into the grip again, sniffed a little more powder.

Then he switched on the engine, engaged gear, and without a backward glance at the gaping cave, the gloomy lake or the bodies that lay between them, he sent the truck rumbling into the dark tunnel curving away through the crowding trees.

High on the sunlit, windswept Snake Pass which links Lancashire with Yorkshire, Peter Pascoe thought, I’m in love.

Even with a trail of blood running from her nose over the double hump of her full lips to peter out on her charming chin, she was grin-like-an-idiot-gorgeous.

‘You OK?’ he said, grinning like an idiot till he realized that in the circumstances this was perhaps not the most appropriate expression.

‘Yes, yes,’ she said impatiently, dabbing at her nose with a tissue. ‘Is this going to take long?’

The driver of her taxi, to whom the question was addressed, looked from the bent and leaking radiator of his vehicle to the jackknifed lorry he had hit and said sarcastically, ‘Soon as I repair this and get that shifted, we’ll be on our way, luv.’

Pascoe, returning from Manchester over the Snake, had been behind the lorry when it jackknifed. Simple humanitarian concern had brought him running to see if anyone was hurt, but now his sense of responsibility as a policeman was taking over. He pulled out his mobile, dialled 999 and gave a succinct account of what had happened.

‘Better set up traffic diversions way back on both sides,’ he said. ‘The road’s completely blocked till you get something up here to shift the lorry. One injury. Passenger in the taxi banged her nose. Lorry driver probably suffering from shock. Better have an ambulance.’

‘Not for me,’ said the woman vehemently. ‘I’m fine.’

She rose from the verge where she’d been sitting and moved forward on long legs, whose slight unsteadiness only added to their sinuous attraction. She looked as if she purposed to move the lorry single-handed. If it had been sentient, she might have managed it, thought Pascoe.

‘Silly cow’d have been all right if she’d put her seat belt on like I told her,’ said the taxi driver.

‘Perhaps you should have been firmer,’ said Pascoe mildly. ‘Who is she? Where’re you headed?’

No reason why he should have asked or the driver answered these questions, but without his being aware of it, over the years Pascoe had developed a quiet authority of manner which most people found harder to resist than mere assertiveness.

The driver pulled out a docket and said, ‘Miss Kelly Cornelius. Manchester Airport. Terminal Three. She’s going to miss her plane.’

He spoke with a satisfaction which identified him as one of that happily vanishing species, the Ur-Yorkshireman, beside whom even Andy Dalziel appeared a creature of sweetness and light. Only a hardcore misogynist could take pleasure in anything which caused young Miss Cornelius distress.

And she was distressed. She returned from her examination of the lorry and gave Pascoe a look of such expressive unhappiness, his empathy almost caused him to burst into tears.

‘Excuse me,’ she said in a melodious voice in which all that was best of American lightness, Celtic darkness, and English woodnotes wild, conjoined to make sweet moan, ‘but your car’s on the other side of this, I guess.’

‘Yes, I’m on my way home to Mid-Yorkshire,’ he said. ‘Looks like I’ll have to turn around and find another way.’

‘That’s what I thought you’d do,’ she said, her voice breathless with delight, as if he’d just confirmed her estimate of his intellectual brilliance. ‘And I was wondering, I know it’s quite a long way back, but how would you feel about taking me to Manchester Airport? I hate to be a nuisance, but you see, I’ve got this plane to catch, and if I miss it, I don’t know what I’ll do.’

Tears brimmed her big dark eyes. Pascoe could imagine their salty taste on his tongue. What she was asking was of course impossible, but (as he absolutely intended to tell Ellie later when he cleansed his conscience by laundering his prurient thoughts in her sight) it was flattering to be asked.

He said, ‘I’m sorry, but my wife’s expecting me.’

‘You could ring her. You’ve got a phone,’ she said with tremulous appeal. ‘I’d be truly, deeply, madly grateful.’

This was breathtaking, in every sense.

He said, ‘Surely there’ll be another plane. Where are you going anyway?’

Silly question. It implied negotiation.

There was just the hint of a hesitation before she answered, ‘Corfu. It’s my holiday, first for years. And it’s a holiday charter, so if I miss it, there won’t be much chance of getting on another, they’re all so crowded this time of year. And I’m meeting my sister and her little boy at the airport, and she’s disabled and won’t get on the plane without me, so it’ll be all our holidays ruined. Please.’

Suddenly he knew he was going to do it. All right, it was crazy, but he was going to have to go back all the way to Glossop anyway and the airport wasn’t much further, well, not very much further…

He said, ‘I’ll need to phone my wife.’

‘That’s marvellous. Oh, thank you, thank you!’

She gave him a smile which made all things seem easy – the drive back, the phone call to Ellie, everything – then dived into the taxi and emerged with a small leather case like a pilot’s flight bag.

Travelling light, thought Pascoe as he stepped back to get some privacy for his call home. The woman was now talking to the taxi driver and presumably paying him off. There seemed to be some disagreement. Pascoe guessed the driver was demanding the full agreed fare on the grounds that it wasn’t his fault he hadn’t got her all the way to Terminal 3.

Terminal 3.

Last time he’d flown out of Manchester, Terminal 3 had been for British Airways and domestic flights only.

You couldn’t fly charter to Corfu from there.

Perhaps the driver had made a mistake.

Or perhaps things had changed at Manchester in the past six months.

But now he was recalling the slight hesitancy before the sob story. And would a young woman on holiday really travel so light…?

Pascoe, he said to himself, you’re developing a nasty suspicious policeman’s mind.

He turned away and began to punch buttons on his phone.

When it was answered he identified himself, talked for a while, then waited.

In the distance he heard the wail of sirens approaching.

A voice spoke in his ear. He listened, asked a couple of questions, then rang off.

When he turned, Kelly Cornelius was standing by the taxi, smiling expectantly at him. A police car pulled up onto the verge beside him. An ambulance wasn’t far behind.

As the driver of the police car opened his door to get out, Pascoe stooped to him. Screened by the car, he pulled out his ID, showed it to the uniformed constable and spoke urgently.

Then he straightened up, waved apologetically to the waiting woman, flourishing his phone as if to say he hadn’t been able to get through before.

He began to dial again, watching as the policemen went across to the taxi and started talking to the driver and the woman.

‘Hi,’ said Pascoe. ‘It’s me. Yes, I’m on my way but there’s been an accident… no, I’m not involved but I am stuck, the road’s blocked, and I’m going to have to divert… yeah, take me when I come… give Rosie a kiss… how’s she been today?… yes, I know, it’s early days… it’ll be OK, I promise… love you… ’bye.’