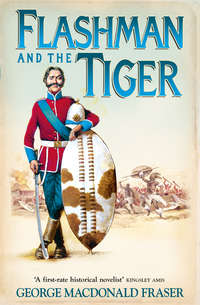

Flashman and the Tiger: And Other Extracts from the Flashman Papers

G.M.F.

You don’t know Blowitz, probably never heard of him even, which is your good luck, although I daresay if you’d met him you’d have thought him harmless enough. I did, to my cost. Not that I bear him a grudge, much, for he was a jolly little teetotum, bursting with good intentions, and you may say it wasn’t his fault that they paved my road to Hell – which lay at the bottom of a salt-mine, and it’s only by the grace of God that I ain’t there yet, entombed in everlasting rock. Damnable places, and not at all what you might imagine. Not a grain of salt to be seen, for one thing.

Mind you, when I say ’twasn’t Blowitz’s fault, I’m giving the little blighter the benefit of the doubt, a thing I seldom do. But I liked him, you see, in spite of his being a journalist. Tricky villains, especially if they work for The Times. He was their correspondent in Paris thirty years ago, and doubtless a government agent – show me the Times man who wasn’t, from Delane to the printer’s devils – but whether he absolutely knew what he was about, or was merely trying to do old Flashy a couple of good turns, I ain’t sure. It was certainly his blasted pictures that led me astray: photographs of two lovely women, laid before my unsuspecting middle-aged eyes, one in ’78, t’other in ’83, and between ’em they landed me in the strangest pickle of my misspent life. Not the worst, perhaps, but bad enough, and deuced odd. I don’t think I understand the infernal business yet, not altogether.

It had its compensations along the way, though, among them the highest decoration France can bestow, the gratitude of two Crowned Heads (one of ’em an out-and-out stunner, much good may it do me), the chance to serve Otto Bismarck a bad turn, and the favours of that delightful little spanker, Mamselle Caprice, to say nothing of the enchanting iceberg Princess Kralta. No … I can’t think too much ill of little Blowitz at the end of the day.

He was reckoned the smartest newsman of the time, better than Billy Russell even, for while Billy was the complete hand at dramatic description, thin red streaks and all, and the more disastrous the better, Blowitz was a human ferret with his plump little claw on every pulse from Lisbon to the Kremlin; he knew everyone, and everyone knew him – and trusted him. That was the great thing: kings and chancellors confided in him, empresses and grand duchesses whispered him their secrets, prime ministers and ambassadors sought his advice, and while he was up to every smoky dodge in his hunt for news, he never broke a pledge or betrayed a confidence – or so everyone said, Blowitz loudest of all. I guess his appearance helped, for he was nothing like the job at all, being a five-foot butterball with a beaming baby face behind a mighty moustache, innocent blue eyes, bald head, and frightful whiskers a foot long, chattering nineteen to the dozen (in several languages), gushing gallantly at the womenfolk, nosing up to the elbows of the men like a deferential gun dog, chuckling at every joke, first with all the gossip (so long as it didn’t matter), a prime favourite at every Paris party and reception – and never missing a word or a look or a gesture, all of it grist to his astounding memory; let him hear a speech or read a paper and he could repeat it, pat, every word, like Macaulay.

Aye, and when the great crises came, and all Europe was agog for news of the latest treaty or rumour of war or collapsing ministry, it was to the Times’ Paris telegrams they looked, for Blowitz was a past master at what the Yankee scribblers call ‘the scoop’. At the famous Congress of Berlin (of which more anon), when the doors were locked for secret session, Bismarck looked under the table, and when D’Israeli asked him what was up, Bismarck said he wanted to be sure Blowitz wasn’t there. A great compliment, you may say – and if you don’t, Blowitz did, frequently.

It was through Billy Russell, who you may know was also a Times man and an old chum from India and the Crimea, that I met this tubby prodigy at the time of the Franco-Prussian farce in ’70, and we’d taken to each other straight off. At least, Blowitz had taken to me, as folk often do, God help ’em, and I didn’t mind him; he was a comic little card, and amused me with his Froggy bounce (though he was a Bohemian in fact), and tall tales about how he’d scuppered the Commune uprising in Marseilles in ’71 by leaping from rooftop to rooftop to telegraph some vital news or other to Paris while the Communards raged helpless below, and saved some fascinating Balkan queen and her beautiful daughter from shame and ruin at the hands of a vengeful monarch, and been kidnapped when he was six and fallen in love with a flashing-eyed gypsy infant with a locket round her neck – sounded deuced like The Bohemian Girl to me, but he swore it was gospel, and part of his ‘Destiny’, which was a great bee in his bonnet.

‘You ask, what if I had slipped from those Marseilles roofs, and been dashed to pieces on the cruel cobbles, or torn asunder by those ensanguined terrorists?’ cries he, swigging champagne and waving a pudgy finger. ‘What, you say, if that vengeful monarch’s agents had entrapped me – moi, Blowitz? What if the gypsy kidnappers had taken another road, and so eluded pursuit? Ah, you ask yourself these things, cher ’Arree –’

‘I don’t do anything o’ the sort, you know.’

‘But you do, of a certainty!’ cries he. ‘I see it in your eye, the burning question! You consider, you speculate, you! What, you wonder, would have become of Blowitz? Or of France? Or The Times, by example?’ He inflated, looking solemn. ‘Or Europe?’

‘Search me, old Blowhard,’ says I rescuing the bottle. ‘All I ask is whether you got to grips with that fascinating Balkan bint and her beauteous daughter, and if so, did you tackle ’em in tandem or one after t’other?’ But he was too flown with his fat-headed philosophy to listen.

‘I did not slip, me – I could not! I foiled the vengeful monarch’s ruffians – it was inevitable! My gypsy abductors took the road determined by Fate!’ He was quite rosy with triumph. ‘Le destin, my old one – destiny is immutable. We are like the planets, our courses preordained. Some of us,’ he admitted, ‘are comets, vanishing and reappearing, like the geniuses of the past. Thus Moses is reflected in Confucius, Caesar in Napoleon, Attila in Peter the Great, Jeanne d’Arc in … in …’

‘Florence Nightingale. Or does it have to be a Frog? Well, then, Madame du Barry –’

‘Jeanne d’Arc is yet to reappear, perhaps. But you are not serious, my boy. You doubt my reason. Oh, yes, you do! But I tell you, everything moves by a fixed law, and those of us who would master our destinies –’ he tapped a fat finger on my knee ‘– we learn to divine the intentions of the Supreme Will which directs us.’

‘Ye don’t say. One jump ahead of the Almighty. Who are you reincarnating, by the way – Baron Munchausen?’

He sat back chortling, twirling his moustache. ‘Oh, ’Arree, ’Arree, you are incorrigible! Well, I shall submit no more to your scepticism méprisant, your dérision Anglaise. You laugh, when I tell you that in our moment of first meeting, I knew that our fates were bound together. “Regard this man,” I thought. “He is part of your destiny.” It is so, we are bound, I, Blowitz, in whom Tacitus lives again, and you … ah, but of whom shall I say you are a reflection? Murat, perhaps? Your own Prince Rupert? Some great beau sabreur, surely?’ He twinkled at me. ‘Or would it please you if I named the Chevalier de Seignalt?’

‘Who’s he when he’s at home?’

‘In Italy they called him Casanova. Aha, that marches! You see yourself in the part! Well, well, laugh as you please, we are destined, you and I. You’ll see, mon ami. Oh, you’ll see!’

He had me weighed up, no error, and knew that on my infrequent visits to Paris, which is a greasy sort of sink not much better than Port Moresby, the chief reason I sought him out was because he was my passport to society salons and the company of the female gamebirds with whom the city abounds – and I don’t mean your poxed-up opera tarts and cancan girls but the quality traffic of the smart hôtels and embassy parties, whose languid ennui conceals more carnal knowledge than you’d find in Babylon. My advice to young chaps is to never mind the Moulin Rouge and Pigalle, but make for some diplomatic mêlée on the Rue de Lisbonne, catch the eye of a well-fleshed countess, and ere the night’s out you’ll have learned something you won’t want to tell your grandchildren.

In spite of looking like a plum duff on legs, Blowitz had an extraordinary gift of attracting the best of ’em like flies to a jampot. No doubt they thought him a harmless buffoon, and he made them laugh, and flattered them something monstrous – and, to be sure, he had the stalwart Flashy in tow, which was no disadvantage, though I say it myself. I suppose you could say he pimped for me, in a way – but don’t imagine for a moment that I despised him, or failed to detect the hard core inside the jolly little flâneur. I always respect a man who’s good at his work, and I bore in mind the story (which I heard from more than one good source) that Blowitz had made his start in France by paying court to his employer’s wife, and the pair of them had heaved the unfortunate cuckold into Marseilles harbour from a pleasure-boat, left him to drown, and trotted off to the altar. Yes, I could credit that. Another story, undoubtedly true, was that when The Times, in his early days on the paper, were thinking of sacking him, he invited the manager to dinner – and there at the table was every Great Power ambassador in Paris. That convinced The Times, as well it might.

So there you have M. Henri Stefan Oppert-Blowitz,1 and if I’ve told you a deal about him and his crackpot notions of our ‘shared destiny’, it’s because they were at the root of the whole crazy business, and dam’ near cost me my life, as well as preventing a great European war – which will happen eventually, mark my words, if this squirt of a Kaiser ain’t put firmly in his place. If I were Asquith I’d have the little swine took off sudden; plenty of chaps would do it for ten thou’ and a snug billet in the Colonies afterwards. But that’s common sense, not politics, you see.

That by the way. It was at the back end of ’77 that the unlikely pair of Blowitz and Sam Grant, late President of the United States, put me on the road to disaster, and (as is so often the case) in the most innocent-seeming way.

Like all retired Yankee bigwigs, Sam was visiting the mother country as the first stage of a grand tour, which meant, he being who he was, that instead of being allowed to goggle at Westminster and Windermere in peace, he must endure adulation on every hand, receiving presentations and the freedom of cities, having fat aldermen and provosts pump his fin, which he hated of all things, listening to endless boring addresses, and having to speechify in turn (which was purgatory to a man who spoke mostly in grunts), with crowds huzzaing wherever he went, the nobility lionising him in their lordly way, and being beset by admiring females from Liverpool laundresses to the Great White Mother herself.

Hard sledding for the sour little bargee, and by the time I met him, at a banquet at Windsor to which I’d been bidden as his old comrade of the war between the states, I could see he’d had his bellyful. Our last encounter had been two years earlier, when he’d sent me to talk to the Sioux and lost me my scalp at Greasy Grass,fn1 and his temper hadn’t improved in the meantime.

‘It won’t do, Flashman!’ barks he, chewing his beard and looking as though he’d just heard that Lee had taken New York. ‘I’ve had as much ceremony and attention as I can stand. D’you know they’re treating me as royalty? It’s true, I tell you! Lord Beaconsfield has ordained it – well, I’m much obliged to him, I’m sure, but I can’t take it! If I have to lay another cornerstone or listen to another artisans’ address or have my hand tortured by some worthy burgess bent on wrestling me to the ground …’ He left off snarling to look round furtive-like in case any of the Quality were in earshot. ‘At least your gracious Queen doesn’t shake hands as though she purposed to break my arm,’ he added grudgingly. ‘Not like the rest of ’em.’

‘Price of fame, Mr President.’

‘Price of your aunt’s harmonium!’ snaps he. ‘And it’ll be worse in Europe, I’ll be bound! Dammit, they embrace you, don’t they?’ He glared at me, as though daring me to try. ‘Here, though – d’you speak French? I know you speak Siouxan, and I seem to recollect Lady Flashman extolling your linguistic accomplishments. Well, sir – do you or don’t you?’

I admitted that I did, and he growled his satisfaction.

‘Then you can do me a signal favour … if you will. They tell me I must meet Marshal Macmahon in Paris, and he hasn’t a word of English – and my French you could write on the back of a postal stamp! Well, then,’ says he, thrusting his beard at me, ‘will you stand up with me at the Invalids or the Tooleries or wherever the blazes it is, and play interpreter?’ He hesitated, eyeing me hard while I digested this remarkable proposal, and cleared his throat before adding: ‘I’d value it, Flashman … having a friendly face at my elbow ’stead of some damned diplomatic in knee-britches.’

Ulysses S. Grant never called for help in his life, but just then I seemed to catch a glimpse, within the masterful commander and veteran statesman, of the thin-skinned Scotch yokel from the Ohio tanyard uneasily adrift in an old so-superior world which he’d have liked to despise but couldn’t help feeling in awe of. No doubt Windsor and Buck House had been ordeal enough, and now the prospect of standing tongue-tied before the French President and a parcel of courtly supercilious Frogs had unmanned him to the point where he was prepared to regard me as a friendly face. Of course I agreed straight off, in my best toady-manly style; I’d never have dared say no to Grant at any time, and I wouldn’t have missed watching him and Macmahon in a state of mutual bewilderment for all the tea in China.

So there I was, a few weeks later, in a gilded salon of the Elysée, when Grant, wearing his most amiable expression, which would have frightened Geronimo, was presented to the great Marshal, a grizzled old hero with a leery look and eyebrows which matched his moustache for luxuriance – a sort of Grant with garlic, he was. They glowered at each other, and bowed, and glowered some more before shaking hands, with Sam plainly ready to leap away at the first hint of an embrace, after which silence fell, and I was just wondering if I should tell Macmahon that Grant was stricken speechless by the warmth of his welcome when Madame Macmahon, God bless her, inquired in English if we’d had a good crossing.

She was still a charmer at sixty, and Sam was so captivated in relief that he absolutely talked to her, which left old Macmahon standing like a blank file. Blowitz, who as usual was to the fore among the attendant dignitaries and crawlers, came promptly to the rescue, introducing me to the Marshal as an old companion-in-arms, sort of, both of us having served in Crimea. This seemed to cheer the old fellow up: ah, I was that Flashman of Balaclava, was I? And I’d done time in the Legion Étrangère also, had I? Why, he was an old Algeria hand himself; we both had sand in our boots, n’est-ce pas, ho-ho! Well, this was formidable, to meet, in an English soldier of all people, a vieille moustache who had woken to the cry of ‘Au jus!’ and marched to the sausage music.2 Blowitz said that wasn’t the half of it: le Colonel Flashman had been a distinguished ally of France in China; Montauban would never have got to Pekin without me. Macmahon was astonished; he’d had no notion. Well, there weren’t many of us left; decidedly we must become better acquainted.

The usual humbug, though gratifying, but pregnant of great effects, as the lady novelists put it. For early in the following May, long after Grant had gone home (having snarled his way round Europe and charmed the Italians by remarking that Venice would be a fine city if it were drained), and I was pursuing my placid way in London, I was dumbfounded by a letter from the French Ambassador informing me that the President of the Republic, in recognition of my occasional services to France, wished to confer on me the Legion of Honour.

Well, bless the dear little snail-eaters, thinks I, for while I’ve collected a fair bit of undeserved tinware in my time, you can’t have too much of it, you know. I didn’t suspect it, but this was Blowitz at work, taking advantage of my meeting with old Macmahon to serve ends of his own. The little snake had discovered a use for me, and decided to put me in his debt – didn’t know Flash too well, did he? At all events, he’d dropped in Macmahon’s ear the suggestion that I was ripe for a Frog decoration, and Macmahon was all for it, apparently, so back to Paris I went in my best togs, had the order (fourth or fifth class, I forget which) hung round my unworthy neck, received the Marshal’s whiskery embrace, and was borne off to Voisin’s by Blowitz to celebrate – and be reminded that I owed my latest glorification to him, and our shared ‘destiny’.

‘What joy compares itself to advancing the fortunes of an old friend to whom one is linked by fate?’ beams he, tucking his napkin under his several chins and diving into his soup. ‘For in serving him, do I not serve myself?’

‘That’s my modest old Blow,’ says I. ‘What d’ye want?’

‘Ah, sceptique! Did I speak of obligation, then? It is true, I hope to interest you in a small affair of mine – oh, but an affair after your own heart, I think, and to our mutual advantage. But first, let us do honour to the table – champagne, my boy!’

So I waited while he gorged his way through half a dozen overblown courses – why the French must clart decent grub with glutinous sauces beats me – and when the waiters had cleared and we were at the brandy and cigars he sighed with repletion, patted his guts, and fished a mounted picture from his pocket.

‘It is a most amusing intrigue, this,’ says he, and presented it with a flourish. ‘Voilà!’

I’m rather a connoisseur of photography, and there was a quality about the present specimen which took my attention at once. It may have been the opulence of the setting, or the delicacy of the hand-colouring, or the careful composition which had placed two gigantic blackamoors with loin-cloths and scimitars among the potted palms, or the playful inclusion of the parakeet and tiny monkey on either side of the Oriental couch on which lounged a lovely odalisque clad only in gold turban and ankle-fetters, her slender body arched to promote jutting young bumpers which plainly needed no support, her lips parted in a sneer which promised unimaginable depravities. A caption read ‘La Petite Caprice’; well, it was a change from Frou-Frou … I tore my eyes away from the potted palms, a mite puzzled. As I’ve said, Blowitz had put me in the way of Society gallops, but never a professional.

‘Très appétissante, non?’ says he.

I tossed it back to him. ‘Which convent is she advertising?’

He clucked indignantly. ‘She is not what you suppose! This is a theatrical picture, made when she was employed at the Folies – from necessity, let me tell you, to finance her studies – serious studies! Such pictures are de rigueur for a Folies comedienne.’

‘Well, I could see she hated posing for it –’

‘Would it surprise you,’ says he severely, ‘to learn that she is a trained criminologist, speaks fluently four languages, rides, fences and shoots, and is a valued member of the département secret of the Ministry of the Interior, at present in our Berlin Embassy … where I was influential in placing her? Ah, you stare! Do I interest you, my friend?’

‘She might, if she was on hand. But since she ain’t, and posing for lewd pictures belies her stainless purity –’

‘Did I say that? No, no, my boy. She is no demi-mondaine, la belle Caprice, but she is … a woman of the world, let us say. That is why she is in Berlin.’

‘And what’s she to do with this small affair after my own heart to our mutual advantage?’

He sat back, lacing his tubby fingers across his pot. ‘As I recall, you were at one time intimate with the German Chancellor, Prince Bismarck, but that you hold him in no affection –’

I choked on my brandy. ‘Thank’ee for the dinner and the Legion of Honour, old Blow,’ says I, preparing to rise. ‘I don’t know where you’re leading, but if it’s to do with him, I can tell you that I wouldn’t go near the square-headed bastard with the whole Household Brigade –’

‘But, my friend, be calm, I beg! Resume the seat, if you please! It is not necessary that you … go near his highness! No such thing … he figures only, how shall I say – at a distance?’

‘That’s too bloody close!’ I assured him, but he protested that I must hear him out; our destinies were linked, he insisted, and he would not dream of a proposal distasteful to me, death of his life – quite the reverse, indeed. So I sat down, and put myself right with a brandy; mention of Bismarck always unmans me, but the fact was I was curious, not least about the delectable Mamselle Caprice.

‘Eh bien,’ says Blowitz, and leaned forward, plainly bursting to unfold his mystery. ‘You are aware that in a few weeks’ time a great conference is to take place at Berlin, of all the Powers, to amend this ridiculous Treaty of San Stefano made by Russia and Turkey?’ I must have looked blank, for he blew out his cheeks. ‘At least you know they have recently been at war in the Balkans?’

‘Absolutely,’ says I. ‘There was talk of us having a second Crimea with the moujiks, but I gather that’s blown over. As for … San Stefano, did you say? Greek to me, old son.’

He shook his head in despair. ‘You have heard of the Big Bulgaria, surely?’

‘Not even of the little ’un.’

He seemed ready to weep. ‘Or the Sanjak of Novi Bazar?’

‘Watch your tongue, if you please. We’re in a public place.’

‘Incroyable!’ He threw up his hands. ‘And it is an educated Englishman, this, widely travelled and of a military reputation! Europe may hang on the brink of catastrophe, and you …’ He smote his fat forehead. ‘My dear ’Arree, will you tell me, then, what events of news you have remarked of late?’

‘Well, let’s see … our income tax went up tuppence … baccy and dog licences, too … some woman or other has sailed round the world in a yacht …’ He was going pink, so just to give him his money’s worth I added: ‘Elspeth’s bought one of these phonographs that are all the rage … oh, aye, and Gilbert and Sullivan have a new piece, and dam’ good, too; the jolliest tunes. “I am an Englishman, be-hold me!” … as you were just saying –’3

‘Enough!’ He breathed heavily. ‘I see I must undertake your political education sur-le-champ. Gilbert and Sullivan, mon dieu!’

And since he did, and I’ll lay odds that you, dear reader, know no more about Big Bulgaria and t’other thing than I did, I’ll set it out as briefly as can be. It’s a hellish bore, like all diplomaticking, but you’d best hear about it – and then you can hold your own with the wiseacres at the club or tea-table.

First off, the Balkans … you have to understand that they’re full of people who’d much rather massacre each other than not, and their Turkish rulers (who had no dam’ business to be in Europe, if you ask me) were incapable of controlling things, what with the disgusting inhabitants forever revolting, and Russia and Austria trying to horn in for their own base ends. By and large we were sympathetic to the Turks, not because we liked the brutes but because we feared Russian expansion towards the Mediterranean (hence the Crimean War, where your correspondent won undying fame and was rendered permanently flatulent by Russian champagne).fn2

At the same time we were forever nagging the Turks to be less monstrous to their Balkan subjects, with little success, Turks being what they are, and when, around ’75, the Bulgars revolted and the Turks slaughtered 150,000 of them to show who was master, Gladstone got in a fearful bait and made his famous remark about the Turks clearing out, bag and baggage. He had to sing a different tune when the Russians invaded Ottoman territory and handed the Turks a handsome licking; we couldn’t have Ivan lording it in the Balkans, and for a time it looked as though we’d have to tackle the Great Bear again – we sent warships to the Dardanelles and Indian regiments to Malta, but the crisis passed when Russia and Turkey made peace, with the San Stefano Treaty.