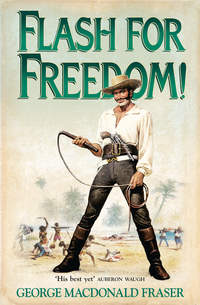

Flash for Freedom!

‘I think it is your bank, Dizzy,’ says Bentinck quietly, at last, his eyes on Bryant. ‘Unless the ladies feel we have played enough.’

The ladies protested against this, and then Bryant cut in again:

‘I’ve played quite enough, thank’ee, and I daresay my partner has, too.’ Mrs Locke looked startled, and Bryant went on:

‘I never thought to see – ah, but let it go!’

And he turned from the table, like a man trying to control himself.

There was a second’s silence, and then they were babbling, ‘What did he say?’ ‘What did he mean?’ and Bentinck was flushed with anger and demanding to know what Bryant was implying. At this Bryant pointed to me, and says:

‘It is really too bad! In a pleasant game, for the ladies, this fellow … I beg your pardon, Lord George, but it is too much! Ask him,’ cries he, ‘to turn out his pockets – his coat pockets!’

It hit me like a dash of icy water. In the shocked hush, I found my hand going to my left-hand coat pocket, while everyone gaped at me, Bentinck took a pace towards me saying, ‘No, stop. Not before the ladies …’ and then my hand came out, and there were three playing cards in it. I was too horrified and bewildered to speak, there was a shriek from one of the females, and a general gasp, and someone muttered: ‘Cheat … oh!’ I could only stare from the cards to Bentinck’s horrified face, to Bryant’s, flushed and exultant, and to Dizzy’s, white with disbelief. Miss Fanny jumped up with a shriek, starting away from me, and then someone was shepherding the females from the room in a terrible silence, leaving me with the stern, disgusted faces and the exclamations of incredulity and amazement. They crowded forward while I stood there, gazing at the cards in my hand – I can see them yet: the king of clubs, the deuce of hearts, and the ace of diamonds.

Bentinck was speaking, and I forced myself to look round at him, with Bryant, D’Israeli, old Morrison, Locke and the others crowding at his back.

‘Gentlemen,’ my voice was hoarse. ‘I … I can’t imagine. I swear to God …’

‘I thought I hadn’t seen the ace of diamonds,’ says someone.

‘I saw his hand go to his pocket, at the last deal.’ This was Bryant.

‘Oh, my Goad, the shame o’t … Ye wicked, deceitful …’

‘The fellow’s a damned sharp!’

‘A cheat! In this house …’

‘Remarkable,’ says D’Israeli, with an odd note in his voice. ‘For a few pence? You know, George, it’s d----d unlikely.’

‘The amount never matters,’ says Bentinck, with a voice like steel. ‘It’s winning. Now, sir, what have you to say?’

I was gathering my wits before this monstrous thing, trying to understand it. God knew I hadn’t cheated – when I cheat, it’s for something that matters, not sweets and ha’pence. And suddenly it hit me like a lightning flash – Bryant coming round to touch Aunt Selina’s hand, standing shoulder to shoulder with me. So this was how he was taking his revenge!

Put me in that situation today, and I’d reason my way out of it, talking calmly. But I was twenty-six then, and panicked – d--n it, if I had been cheating I’d have been ready for them, with my story cut and dried, but for once I was innocent, and couldn’t think what to say. I dashed the cards down and faced them.

‘It’s a b----y lie!’ I shouted. ‘I didn’t cheat, I swear it! My God, why should I? Lord George, can you believe it? Mr D’Israeli, I appeal to you! Would I cheat for a few coppers?’

‘How came the cards in your pocket, then?’ demands Bentinck.

‘That little viper!’ I shouted, pointing at Bryant. ‘The jealous little b-----d placed them there, to disgrace me!’

That set up a tremendous uproar, and Bryant, blast his eyes, played it like a master. He took a step back, gritted his teeth, bowed to the company, and says:

‘Lord George, I leave it to you to determine the worth of a foul slander from a proven cheat.’

And then he turned, and strode from the room. I could only stand raging, and then as I saw how he had foxed me – my God, ruined me, and before the best in the land, I lost control altogether. I sprang for the door, bawling after him, someone caught my sleeve, but I threw him off, and then I had the door open and was plunging through in pursuit.

There was a hubbub behind me, and a sudden squeal of alarm ahead, for there were ladies at the head of the stairs, their white faces turned towards me. Bryant made off at the sight of me, and in blind passion I hurled myself after him. I had only one thought: to catch the undersized little squirt and pound him to death – sense, decency and the rest were forgotten. I got my hand on his collar at the top of the stairs, while the females screamed and shrank back; I wrenched him round, his face grey with fear, and shook him like a rat.

‘You foul vermin!’ I roared. ‘Try to dishonour me, would you, you scum of … of the Eighth Hussars!’ And as I swung him left-handed before me, I drew back my right fist and with all my strength, smashed it into his face.

Nowadays, when I’m day-dreaming over the better moments of my misspent life – galloping Lola Montez and Elspeth and Queen Ranavalona and little Renee the creole and the fat dancing-wench I bought in India whose name escapes me, and having old Colin Campbell pinning the V.C. to my unworthy breast, and receiving my knighthood from Queen Victoria (and she in tears, maudlin little woman), and breaking into the Ranee’s treasure-cellar and seeing all that splendid loot laid out for the taking – when I think back on these fine things, the recollection of hitting Tommy Bryant invariably comes back to me. God knows it was a nightmare at the time, but in retrospect I can’t think of inflicting a hurt that I enjoyed more. My fist caught him full on the mouth and nose so hard that his collar was jerked clean out of my hand, and he went hurtling head foremost down the staircase like an arrow, bouncing once before crashing to rest in the hall, his limbs all a-sprawl.

There were shrieks of hysterical females in my ears, and hands seizing my coat, and men scampering down to lift him up, but all I remember is seeing Fanny’s face turned towards me in terror, and Bentinck’s voice drifting up the staircase:

‘My God, I believe he’s killed him!’

As it turned out, Bentinck was wrong, thank God; the little louse didn’t die, but it was a near-run thing. Apart from a broken nose, his skull was fractured in the fall, and for a couple of days he hung on the edge, with a Bristol horse-leech working like fury to save him from going over. Once he regained consciousness, and had the impertinence to say, ‘Tell Flashman I forgive him with all my heart,’ which cheered me up, because it indicated he was going to live, and wanted to appear a forgiving Christian; if he’d thought he was dying he’d have d----d me to hell and beyond.

But after that he lost consciousness again, and I went through the tortures of the pit. They had confined me to my room – Locke was a justice of the peace – and kept me there with the muff Duberly sitting outside the door like a blasted water-bailiff. I was in a fearful sweat, for if Bryant kicked the bucket it would be a hanging matter, no error, and at the thought of it I could only lie on my bed and quake. I’d seen men swing, and thought it excellent fun, but the thought of the rope rasping on my neck, and the blind being pulled over my brows, and the fearful plunge and sickening snap and blackness – my God, it had me vomiting in the corner. Well, I’ve had the noose under my chin since then, and waited blubbering for them to launch me off, and even the real thing seems no worse, looking back, than those few days of waiting in that bedroom, with the yellow primroses on the wallpaper, and the blue and red carpet on the floor with little green tigers woven into it, and the print of Harlaxton Manor, near Grantham, Lincolnshire, the seat of one John Longden, Esq., which hung above the bed – I can still recite the whole caption.

With the thought of the gallows driving everything else from my mind, it was small consolation to learn from Duberly – who seemed to be in a mortal funk himself over the whole business – that there was by no means complete agreement that I had been caught cheating. D’Israeli – he was clever, I’ll say that for him – had sensibly pointed out that a detected cheat wouldn’t have hauled the evidence out of his pocket publicly as soon as he was challenged. He maintained I would have protested, and refused to be searched – he was quite right, of course, but most of the other pious hypocrites disagreed with him, and the general feeling was that I was a fraud and a dangerous maniac who would be well served if I finished up in the prison lime-pit. Whatever happened, it was a hideous scandal; the house had emptied as if by magic next day, Mrs Locke was in a decline, and her husband was apparently only waiting to see how Bryant fared before turning me over to the police.

I don’t know, even now, what was determined, or who determined it, in those few days, except that old Morrison was obviously up to the neck in it. Whatever happened to Bryant, my political career was obviously over before it had begun; at best I was probably disgraced as a cheat, and liable to sentence for assault – that was if Bryant lived. In any event, I was a liability to Morrison henceforth, and whether he decided to try to get rid of me permanently, or planned simply to get me out of harm’s way for a time, is something on which I’ve never made up my mind. In fact, I don’t suppose he cared above half whether I lived or died, so long as his own interests weren’t harmed.

He came to see me on the fifth day, and told me that Bryant was out of danger, and I was so relieved that I was almost happy as I listened to him denouncing me for a wastrel, a fornicator, a cheat, a liar, a brute, and all the rest of it – I couldn’t fault a word of it, anyway. When he was done, he plumped down, breathing like a bellows, and says:

‘My certie, but ye’re easier oot o’ this than ye deserve. It’s no’ your fault the mark o’ Cain isnae on yer broo this day – a beast, that’s whit ye are, Flashman, a ragin’, evil beast!’ And he mopped his face. ‘Weel, Locke isnae goin’ tae press charges – ye have me tae thank for that – and this fellow Bryant’ll keep mum. Huh! A few hundred’ll tak’ care of him – he’s anither “officer and gentleman” like yersel’. I could buy the lot o’ ye! Jist trash.’ He snarled away under his breath, and shot me a look. ‘But we’ll no’ hush up the scandal, for a’ that. Ye cannae come home – ye’re aware o’ that, I suppose?’

I didn’t argue; I couldn’t, but I was ill-advised enough to mutter something about Elspeth, and for a moment I thought he would strike me. His face went purple, and his teeth chattered.

‘Mention her name tae me again – jist once again, and as Goad’s my witness I’ll see ye transported for this week’s work! Ye’ll rue the day ye ever set eyes on her – aye, as I have done, most bitterly. Goad alone knows what I and mine have done tae be punished by … you!’

Well, at least he didn’t pray over me, like Arnold; he was a different kind of hypocrite, was Morrison, and as a man of business he didn’t waste overmuch holy vituperation before getting down to cases.

‘Ye’ll be best oot o’ England for a spell, until this d---able business has blown by – if it ever does. Your fine relatives can mak’ your peace wi’ the Horse Guards – this kind o’ scandal’ll be naethin’ new there, I daresay. For the rest, I’ve been at work tae arrange matters – and whether ye like it or not, my buckie, ye’ll jump as I whistle. D’ye see?’

‘I suppose I’ve no choice,’ says I, and then, deciding it would be politic to grovel to the old b-----d, I added: ‘Believe me, sir, I feel nothing but gratitude for what you are doing, and –’

‘Hold your tongue,’ says he. ‘Ye’re a liar. There’s no more tae be said. Now, ye’ll pack yer valise, and go at once tae Poole, and there take a room at the “Admiral” and wait until ye hear from me. Not a word to a soul, and never stir out – or ye’ll find my protection and Locke’s is withdrawn, and that’ll be a felon’s cell for ye, and beggary tae follow. There’s money,’ says he, and dropping a purse on the table he turned on his heel and stamped out.

I made no protest; he had me by the neck, and I didn’t waste time reflecting on the eagerness with which my relatives and friends have always striven to banish me from England whenever opportunity offered – my own father, Lord Cardigan, and now old Morrison. They could never get shot of me fast enough. And, as on previous occasions, there was no room for argument; I would just have to go, and see what the Lord and John Morrison provided.

I slipped away from the house at noon, and was in Poole by nightfall. And there I waited a whole week, fretting at first, but gradually getting my spirits back. At least I was free, when I might have been going to the condemned hold; whatever lay in front of me, I’d come back to England eventually – it might be no more than a year, and by that time the trouble would be half-forgotten. Curiously enough, the assault on Bryant would be far less to live down than the business over the cards, but the more I thought about that, the more it seemed that no sensible men would take Bryant’s word against mine – he was known for a toady and a dirty little hound, whereas I, quite aside from my popular fame, was bluff, honest Harry to everyone who thought they knew me. Indeed, I even toyed with the notion of going back to town and brazening the thing then and there, but I hadn’t the gall for that. It was all too fresh, and Morrison would have thrown me into the gutter for certain. No, I would just have to take my medicine, whatever it was; I’ve learned that there’s no sense in kicking against the prick – a phrase which fits old Morrison like a glove. I would just have to make the best of whatever he had in store for me.

What that was I discovered on the eighth day, when a man called to see me just as I was finishing breakfast. In fact, I had finished, and was just chivvying after the servant lass who had come to clear away the dishes from my room; I had chased her into a corner, and she was bleating that she was a good girl, which I’ll swear she wasn’t, when the knock sounded; she took advantage of it to escape, admitting the visitor while she straightened her cap and snapped her indignation at me.

‘Sauce!’ says she. ‘I never –’

‘Get out,’ says the newcomer, and she took one look at him and fled.

He kicked the door to with his heel and stood looking at me, and there was something in that look that made me bite back the d--n-your-eyes I’d been going to give him for issuing orders in my room. At first glance he was ordinary-looking enough; square built, middle height, plain trousers and tight-buttoned jacket with his hands thrust into the pockets, low-crowned round hat which he didn’t trouble to remove, and stiff-trimmed beard and moustache which gave him a powerful, business-like air. But it wasn’t that that stopped me: it was the man’s eyes. They were as pale as water in a china dish, bright and yet empty, and as cold as an ice floe. They were wide set in his brown, hook-nosed face, and they looked at you with a blind fathomless stare that told you here was a terrible man. Above them, on his brow, there was a puckered scar that ran from side and side and sometimes jerked as he talked; when he was enraged, as he often was, it turned red. Hollo, thinks I, here’s another in my gallery of happy acquaintances.

‘Mr Flashman?’ says he. He had an odd, husky voice with what sounded like a trace of North Country. ‘My name is John Charity Spring.’

It seemed d----d inappropriate to me, but he was evidently well enough pleased with it, for he sat himself down in a chair and nodded me to another. ‘We’ll waste no time, if you please,’ says he. ‘I’m under instructions from my owner to take you aboard my vessel as supercargo. You don’t know what that means, I daresay, and it’s not necessary that you should. I know why you’re shipping with me; you’ll perform such duties as I suppose to be within your power. Am I clear?’

‘Well,’ says I, ‘I don’t know about that. I don’t think I care for your tone, Mr Spring, and –’

‘Captain Spring,’ says he, and sat forward. ‘Now see here, Mr Flashman, I don’t beat about. You’re nothing to me; I gather you’ve half-killed someone and that you’re a short leap ahead of the law. I’m to give you passage out, on the instructions of Mr Morrison.’ Suddenly his voice rose to a shout, and he crashed his hand on the table. ‘Well, I don’t give a d--n! You can stay or run, d’ye see? It’s all one to me! But you don’t waste my time!’ The scar on his head was crimson, and then it faded and his voice dropped. ‘Well?’

I didn’t like the look of this one, I can tell you. But what could I do?

‘Well,’ says I, ‘you say Mr Morrison is your ship’s owner – I didn’t know he had ships.’

‘Part owner,’ says he. ‘One of my directors.’

‘I see. And where is your ship bound, Captain Spring, and where are you to take me?’

The pale eyes flickered. ‘We’re going foreign,’ says he. ‘America, and home again. The voyage may last six months, so by Christmas you’ll be back in England. As supercargo you take a share of profit – a small share – so your voyage won’t be wasted.’

‘What’s the cargo?’ says I, interested, because I remembered hearing that these short-haul traders on the Atlantic run did quite well.

‘General stuffs on the way out – Brummagem, cloths, some machinery. Cotton, sugar, molasses and so forth on the trip home.’ He snapped the words out. ‘You ask too d----d many questions, Mr Flashman, for a runner.’

‘I’m not all that much of a runner,’ says I. It didn’t sound too bad a way of putting by the time till the Bryant business was past. ‘Well, in that case, I suppose –’

‘Good,’ says he. ‘Now then: I know you’re an Army officer, and it’s in deference to that I’m making you supercargo, which means you mess aft. You’ve been in India, for what that’s worth – what d’you know of the sea?’

‘Little enough,’ says I. ‘I’ve voyaged out and home, but I sailed in Borneo waters with Rajah Brooke, and can handle a small boat.’

‘Did you now?’ The pale eyes gleamed. ‘That means you’ve been part-pirate, I daresay. You look like it – hold your tongue, sir, it doesn’t matter to me! I’ll only tell you this: on my ship there is no free-and-easy sky-larking! I saw that slut in here just now – well, henceforth you’ll fornicate when I give you leave! By God, I’ll not have it otherwise!’ He was shouting again; this fellow’s half-mad, thinks I. Then he was quiet. ‘You have languages, I understand?’

‘Why, yes. French and German, Hindoostani, Pushtu – which is a tongue …’

‘… of Northern India,’ says he impatiently. ‘I know. Get on.’

‘Well, a little Malay, a little Danish. I learn languages easily.’

‘Aye. You were educated at Rugby – you have the classics?’

‘Well,’ says I, ‘I’ve forgotten a good deal …’

‘Hah! Hiatus maxime deflendus,’fn1 says this amazing fellow. ‘Or if you prefer it, Hiatus valde deflendus.’ He glared at me. ‘Well?’

I gaped at the man. ‘You mean? – oh, let’s see. Great – er, letting down? Great –’

‘Christ’s salvation!’ says he. ‘No wonder Arnold died young. The priceless gift of education, thrown away on brute minds! You speak living languages without difficulty, it seems – had you not the grace to pay heed, d--n your skin, to the only languages that matter?’ He jumped up and strode about.

I was getting tired of Mr Charity Spring. ‘They may matter to you,’ says I, ‘but in my experience it’s precious little good quoting Virgil to a head-hunter. And what the d---l has this to do with anything?’

He stood lowering at me, and then sneered: ‘There’s your educated Englishman, right enough. Gentlemen! Bah! Why do I waste breath on you? Quidquid praecipies, esto brevis,fn2 by God! Well, if you’ll pack your precious traps, Mr Flashman, we’ll be off. There’s a tide to catch.’ And he was away, bawling for my account at the stairhead.

It was obvious to me that I had fallen in with a lunatic, and possibly a dangerous one, but since in my experience a great many seamen are wanting in the head I wasn’t over-concerned. He paid not the slightest heed to anything I said as we made our way down to the jetty with my valise behind on a hand-cart, but occasionally he would bark a question at me, and it was this that eventually prodded me into recollecting one of the few Latin tags which has stuck in my mind – mainly because it was flogged into me at school as a punishment for talking in class. He had been demanding information about my Indian service, mighty offensively, too, so I snapped at him:

‘Percunctatorem fugitus nam garrulus idem est’,fn3 which I thought was pretty fair, and he stopped dead in his tracks.

‘Horace, by G-d!’ he shouted. ‘We’ll make something of you yet. But it is fugito, d’ye see, not fugitus. Come on, man, make haste.’

He got little opportunity to catechise me after this, for the first stage of our journey was in a cockly little fishing boat that took us out into the Channel, and since it was h--lish rough I was in no condition for conversation. I’m an experienced sailor, which is to say I’ve heaved my guts over the rail into all the Seven Seas, and before we were ten minutes out I was sprawled in the scuppers wishing to God I’d gone back to London and faced the music. This spewing empty misery continued, as it always does, for hours, and I was still green and wobbly-kneed when at evening we came into a bay on the French coast, and sighted Mr Spring’s vessel riding at anchor. Gazing blearily at it as we approached, I was astonished at its size; it was long and lean and black, with three masts, not unlike the clippers of later years. As we came under her counter, I saw the lettering on her side: it read Balliol College.

‘Ah,’ says I to Spring, who was by me just then. ‘You were at Balliol, were you?’

‘No,’ says he, mighty short. ‘I am an Oriel man myself.’

‘Then why is your ship called Balliol College?’

I saw his teeth clench and his scar darkened up. ‘Because I hate the b----y place!’ he cried in passion. He took a turn about and came back to me. ‘My father and brothers were Balliol men, d’you see? Does that answer you, Mr Flashman?’

Well, it didn’t, but at that moment my belly revolted again, and when we came aboard I had to be helped up the ladder, retching and groaning and falling a-sprawl on the deck. I heard a voice say, ‘Christ, it’s Nelson’, and then I was half-carried away, and dropped on a bunk somewhere, alone in my misery while in the distance I heard the hateful voice of John Charity Spring bawling orders. I vowed then, as I’ve vowed fifty times since, that this was the last time I’d ever permit myself to be lured aboard a ship, but my mind must still have been working a little, because as I dropped off to sleep I remember wondering: why does a British ship have to sail from the French coast? But I was too tired and ill to worry just then.

Sometime later someone brought me broth, and having spewed it on to the floor I felt well enough to get up and stagger on deck. It was half-dark, but the stars were out, and to port there were lights twinkling on the French coast. I looked north, towards England, but there was nothing to be seen but grey sea, and suddenly I thought, my G-d, what am I doing here? Where the deuce am I going? Who is this man Spring? Here I was, who only a couple of weeks before had been rolling down to Wiltshire like a lord, with the intention of going into politics, and now I was shivering with sea-sickness on an ocean-going barque commanded by some kind of mad Oxford don – it was too much, and I found I was babbling to myself by the rail.

It’s always the way, of course. You’re coasting along and then the current grips you, and you’re swept into events and places that you couldn’t even have dreamed about. It seemed to have happened so quickly, but as I looked miserably back over the past fortnight there wasn’t, that I could see, anything I could have done that would have prevented what was now happening to me. I couldn’t have resisted Morrison, or refused Spring – I’d had to do what I was told, and here I was. I found myself blubbering as I gazed over the rail at the empty waste of sea – if only I hadn’t got lusty after that little b---h Fanny, and played cards with her, and hit that swine Bryant – ah, but what was the use? It was done, and I was going God knew where, and leaving Elspeth and my life of ease and drinking and guzzling and mounting women behind. But it was too bad, and I was full of self-pity and rage as I watched the water slipping past.