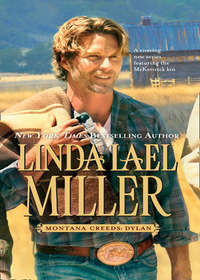

Montana Creeds: Dylan

Kristy felt an uneasy prickle in the pit of her stomach. “Floyd, what are you getting at?”

“I think there might be a body buried on the place,” Floyd said.

Kristy’s mouth dropped open, and her heart stopped, then raced. The monster-memory stirred in the depths of her brain. “A body?”

Floyd sighed. “I could be wrong,” he said, but the expression on his face said he didn’t think so.

“Good God,” Kristy said, too stunned to say anything else and, at the same time, strangely not surprised.

The sheriff looked pained. “There was a man—worked for your daddy one summer when you were just a little thing. Some drifter—I never knew his name for certain. Men like him came and went all the time, stopping to earn a few dollars on some ranch. But one night, late, Tim woke me up with a phone call and said there was bad trouble, and I ought to get out there quick. He didn’t sound like himself—for a moment or two, I thought I was talking to a prowler. Turned out he’d caught this drifter fella sneaking out of the house with some of your mother’s jewelry and what cash they had on hand, which was plenty, because they’d sold some cattle at auction that day. There was a fight, that was all Tim would tell me. That there’d been a fight. I dressed and headed for the ranch, soon as I could. And when I got there, your dad changed his story. Said the drifter had moved on and good riddance to him.”

Dread welled up inside Kristy, but she said, “That must have been the truth, then.” She’d never known her father to lie about anything, however expedient it might be.

But Sheriff Book shook his head again. His eyes seemed to sink deeper into his head, and there were shadows under them. “I took his word for it, because he was my best friend, but there was more to the story, and I knew it. Tim looked worse than he’d sounded on the phone. It was a cold night, but he was sweating, and he had dirt under his nails, and on his clothes, too. You know he always cleaned up before supper, Kristy, and this was well after midnight.”

Kristy couldn’t speak, couldn’t bring herself to ask the obvious question: Did Sheriff Book think her father had killed a man?

“Few days later,” the sheriff went on, clearly forcing out the words, “on a Sunday morning, I came by the ranch for a look around, when I knew you and your folks were at church. And I found what I figured was a freshly dug grave in that copse of trees over near where Tim’s property and the Creed place butt up.”

Kristy felt a surge of relief—he’d seen Sugarfoot’s grave that morning, not that of a human being—but it was gone in a moment. Back then, Sugarfoot had been alive and well.

Floyd reached across the table, squeezed her ice-cold hand. “I asked Tim what was there. He said an old dog had strayed into his barn and died there, and he’d buried the poor critter in the midst of those trees.” He thrust out another sigh. “I was the sheriff. I should have done some digging, both literal and figurative, but I didn’t. I wanted to believe your dad, so I did, but I’ve always wondered, and now that I’m about to retire, I’ve got to know for sure. It isn’t just the coffee that keeps me up at night, it’s certain loose ends.”

Kristy thought she was going to be sick. “You’re going to—to exhume—”

Floyd nodded. “I know Sugarfoot’s buried there, Kristy,” he said gruffly, hardly able to meet her gaze, “and I’ll do my best not to disturb his remains too much. But I’ve got to see, once and for all, if there’s a dog in that grave with him—or a man.”

“You seriously think my father—your best friend—would murder someone and then go to such lengths to hide the body?” Now, Kristy was light-headed. Her heart pounded, and the smell of paint, unnoticed before, brought bile scalding up into the back of her throat.

Don’t remember, whispered a voice in the shadowy recesses of her mind, where migraines and nightmares lurked. Don’t remember.

“I think,” Sheriff Book said quietly, “that there was a fight, and things got out of hand. If Tim did kill that drifter, it was an accident, and nobody will ever convince me otherwise. He’d have been real upset, Tim, I mean, with you and your mother in the house—that would have made the fight one he couldn’t afford to lose. In Tim’s place, I’d have been scared as hell of what that fella might do if I wasn’t up to stopping him.”

Kristy got up, meaning to bolt for the bathroom, then sat down again with a plunk. “But Dad called you,” she muttered. “Would he have done that if he’d killed somebody?”

“He was in a panic, Kristy. He probably called first and thought later.”

“Dad’s gone, and so is Mom. You’re about to retire. Can’t we just let this whole thing … lie?”

“If we can live with knowing what we do. I don’t think I can, not anymore—I’ve got an ulcer to show for it as it is. Can you just go on from here like nothing was ever said, Kristy?”

She bit down on her lower lip. “No,” she said miserably.

If there were human remains buried with Sugarfoot—more likely beneath him—the scandal would rock the whole state of Montana. Tim Madison’s memory, that of a decent, hardworking, honorable man, would be fodder for all sorts of speculation.

How would she handle that?

“Why now?” she asked, closing her eyes briefly in the hope that the room would stop tilting from side to side. “After all this time, Floyd, why now?”

“I told you,” he replied gently. “My retirement. And with that land going up for sale, and some jerk from Hollywood bound on bringing in bulldozers to make room for tennis courts and whatnot—”

Kristy froze. She’d known, of course, that someone would buy Madison Ranch eventually. It was prime real estate. But not once had she considered the possibility that that someone might destroy poor Sugarfoot’s grave.

Tears filled her eyes, and all the old wounds opened at once.

“I’m sorry,” Sheriff Book said.

“When he died,” Kristy murmured, “Sugarfoot, I mean—I wanted to die, too. Crawl right into that grave with him and let them cover me with dirt.”

“You’d just lost your mother then,” Floyd reminded her. “And your dad was already sick. It was a lot for one young girl to bear up under. But you did bear up, Kristy. You kept going, kept living, like you were supposed to.”

A long, difficult silence fell. Kristy broke it with, “You do realize what an uproar this is going to cause, if you find—find something.”

Grimly, Floyd nodded. “Might be I’m wrong. There’s no need to get the community all riled up if there’s really a dog sharing that grave with Sugarfoot. I can keep the whole thing quiet, Kristy, at least for a while. But this is Stillwater Springs, and folks are always flapping their jaws. Word could get out, and that’s why I came over here to talk to you first. So you’d know ahead of time, in case—well, you know.”

Kristy nodded.

The sheriff stood to go. “You going to be all right?” he asked. “I could call somebody, if you want.”

“Call somebody?” Kristy echoed stupidly. Who? Who in the whole wide, upside-down, messed-up world would drop everything and rush over to hold the librarian’s hand?

Dylan, she thought.

“Maybe you oughtn’t to be alone.”

“I’m fine,” Kristy said. Stock answer.

Major lie.

“Lock up behind me,” Floyd said.

Kristy nodded.

But he’d been gone a long time before she even got out of her chair.

THE HOUSE WAS HABITABLE, as it turned out, if sparsely furnished. Dylan figured he and Bonnie could live there, in comfort if not style, but he’d need to rig up some kind of bed for her, get her a dresser.

More shopping, he thought unhappily.

And with a two-year-old.

“Whoopee,” he muttered.

“Potty,” Bonnie said.

“Learn another word,” Dylan replied. The little pink toilet was still at Cassie’s place, so he had to lift Bonnie onto the john again, bare-assed, and wait it out.

In the end, Cassie offered to babysit at her place while he laid in grub and the other necessities.

He bought Bonnie a miniature bed, one step up from a crib, with side rails that could be raised and lowered. It was white, with gold trim—French provincial, the saleswoman at the only furniture store in Stillwater Springs called it. The piece, she said, was designed to grow with the child.

Dylan paid cash and the woman promised an early-morning delivery. He still needed some other stuff, but since he meant to tear down the house anyway, he couldn’t see torturing himself by buying a decent couch and a new dinette set right then. He could get all that later—or maybe the trailer he meant to lease and set up on the property as temporary digs would have some rigging in it.

But the kid would need milk in the morning, to put in her sippy-thing, and cereal, too.

So he braved the grocery store in town.

Once he’d carted everything back out to the ranch and put it away, he headed back to Cassie’s to pick up Bonnie. She could sleep on the bed that night—it had been there when Briana moved in—and he’d take the lumpy old couch.

At least they’d be in their own place, he and Bonnie. It was a start.

As he drove past the casino, his truck wanted to pull in, but for the time being, he was out of the poker business. He was, after all, a father.

He had responsibilities now.

And strange as it seemed, he liked the feeling.

It was all good—except for the potty thing and the flying spaghetti.

He definitely needed a wife, if he was going to pull this thing off.

He immediately thought of Kristy.

“Oh, sure,” he told himself out loud. “Just walk right into the library, one fine day, and suggest letting bygones be bygones because, lo and behold, you’ve got a two-year-old daughter and you could sure use a hand raising her.”

Put like that, it sounded pretty damn lame.

And Kristy would probably bash him over the head with the nearest heavy book.

Still, Bonnie needed a mother, and he couldn’t think of a better candidate than Kristy Madison, with her soft storyteller’s voice and her calm practicality. If he’d had to get somebody pregnant, why couldn’t it have been her, instead of Sharlene?

Now there was a useless question.

After what had gone down the day of Jake’s funeral, Kristy had crossed him off her list, gotten herself engaged to Mike Danvers. Good old solid Mike, student body president, Boy Scout and future owner of his dad’s Chevrolet dealership.

He wouldn’t get arrested for fighting with his own brothers after a family funeral, not Mike. No sir, he was the original solid citizen, not a hell-raising Creed. One word from Kristy and he’d probably beat feet down to the jewelry store to make a down payment on that honking diamond he’d given her.

Since Dylan was thinking these thoughts, and some that were even worse, when he pulled into Cassie’s yard, it took him an extra second or two to realize that the big white Cadillac SUV parked next to the teepee probably belonged to Tyler.

The rodeo insignia in the back window clenched it. Only champions had those silver-buckle decals, and Tyler had been a world-class bronc-buster, among other things.

He did TV commercials, too, and posed for cowboy calendars, half-naked. Taking a page from Dylan’s book, he’d done some stunt work, too, though mercifully they’d never wound up on the same movie set.

Dylan was flat-out not ready to deal with his younger brother just then, but leaving wasn’t an option, either. For one thing, he didn’t run from confrontations, unless they were with women. He’d come for Bonnie, and he wasn’t leaving without her.

So he got out of the truck and walked toward Cassie’s front door.

Best get it over with. He’d pass the word to Tyler, if Cassie hadn’t done it already, that Logan had been trying to get in touch with him, get Bonnie and all her assorted gear, and leave.

Tyler was on the floor when Dylan walked in, on his hands and knees, with Bonnie on his back, one hand gripping the back of his shirt collar, the other raised in the air, bronc-buster style.

And she was laughing as he bucked, careful not to throw her.

She was a Creed, all right. Thank God she was a girl, or she’d probably end up on the circuit, risking life and limb for a rush of adrenaline and some elusive prize money.

Of the three Creed brothers, Tyler was the youngest, and the tallest, and the one with the hottest temper. His hair was as dark as Cassie’s, and he wore it long enough to brush his collar.

He turned his head, saw Dylan and stopped bucking. Eased Bonnie off his back and got to his feet.

His deep blue eyes were arctic as he straightened to his full height.

As a kid, he’d had music in him, so much that it flowed out through the strings of his cheap guitar and just about everything he did. Between Jake’s drunken escapades and his mother’s suicide when he was still young, though, something had shut down inside him and never started up again.

“Logan wants to talk to you,” Dylan said, because with Tyler, even “hello” was shaky ground.

“So I hear,” Tyler answered. “Of course, I don’t give a rat’s ass.”

Cassie wooed Bonnie into the kitchen, promising her a cookie, after casting worried glances from one Creed brother to the other.

“If you’re trying to get my back up, Ty, you’re going to have to do better than that. What brings you back to Stillwater Springs?”

“I was about to ask you the same thing,” Tyler answered, turning to look when Bonnie’s giggle chimed from the kitchen. “Cute kid,” he added, and for a fraction of a second, his eyes warmed. “Bonnie, isn’t it?”

“That’s right,” Dylan said, still waiting for the explosion. He and Tyler had had several run-ins over the years; the brawl after Jake’s funeral was only one of them. A couple of seasons back, they’d collided at the same rodeo, and Ty’s girlfriend, probably wanting to make him jealous, had been all over Dylan.

He hadn’t taken the bait, but the girlfriend—he couldn’t recall her name—had ditched Tyler, stayed out all night and claimed she’d been with Dylan, in his hotel room. It wasn’t true—for one thing, there’d been another woman sharing his bed, and he wasn’t into threesomes—but Tyler, with that perennial chip on his shoulder, hadn’t believed him.

There would have been a fight, right there behind the chutes that day at the rodeo, if ten other cowboys hadn’t jumped in to pull them apart.

“I’ll be leaving now,” Tyler said. “I just came by to say hello to Cassie.”

Dylan nodded. There had to be more to it, of course—Tyler hadn’t set foot in Stillwater Springs, as far as he knew, since Sheriff Book turned them all loose the morning after Jake was laid to rest—but he knew better than to try to get an answer out of his brother.

“See you,” he said.

“Not if I see you first,” Tyler replied. As kids, that had been a running joke. Now, Tyler meant it.

A bleak feeling settled over Dylan. He and Logan were speaking, anyway, though they still had things to work through. But that wasn’t going to happen with Tyler, he could tell.

Tyler was a loner, and he clearly intended to stay that way.

“What’s he doing here?” Dylan asked Cassie, in the kitchen, after Tyler left. The SUV started up with a roar outside.

She sat at the table, Bonnie on her knee, deftly spooning toddler grub into the kid’s mouth. “Why didn’t you ask him?” she asked. She’d been trying for years to get the three of them to reconcile and act like brothers, and despite an almost complete lack of success, she still seemed to think it could happen.

“Might as well ask the totem pole down at the library,” Dylan said, opening the fridge and helping himself to a can of soda. Pre-Bonnie, he’d have had a beer, but since you never knew when you might have to rush a kid to the emergency room with some sudden malady, he figured he’d better lay off the brew.

Cassie smiled to herself. “You’ve been to the library?”

Dylan popped the top on the soda can and took a swig. “I can read, you know. I was dyslexic as a kid, but I’ve learned to compensate.”

“That isn’t what I meant,” Cassie said sweetly. How many nights had she sat with him, at that same table, going over the “special lessons” he’d been assigned after a battery of reading tests?

“Ah,” Dylan said. “Yes. Did I see Kristy—that’s what you’re asking.”

“And?”

“I saw her.”

“Well, don’t overwhelm me with information, here.”

Dylan sighed. “I saw her. She’s still a looker. She’s still got a way with kids. End of story.”

“Or the beginning,” Cassie said, smiling at Bonnie.

“Don’t get any ideas,” Dylan warned, though when it came to Kristy, he’d been getting ideas himself. Cassie couldn’t possibly know that, unless she used her X-ray vision.

“Poor Kristy,” she said, looking solemn now, even sad. Frowning as she gazed over Bonnie’s head, past Dylan, to some unseen world only she could navigate.

“What do you mean, ‘poor Kristy’?” Dylan asked, knowing he shouldn’t, but too worried to resist. When Cassie worried about people, they tended to meet with severe and immediate problems.

“She could use a friend, that’s all,” Cassie mused.

It wasn’t all, of course.

Dylan set the soda can aside with a thump. He’d have tossed it, but Cassie recycled. “What’s going on?” he demanded quietly. “You didn’t have one of your dreams.?”

“No,” Cassie said. “I just know these things.” She brightened. “Call it an old Indian trick.”

“Cassie,” Dylan pressed. “Tell me.”

“Go see her,” Cassie replied, looking up into his face. “She’s alone, at her place. I’ll look after Bonnie, give her a bath and supper and put her to bed.”

“I can’t just show up on her doorstep, Cassie. What am I supposed to say? ‘Hi, my foster grandmother sent me’?”

“You’ll think of something.”

“I was planning on taking Bonnie out to the ranch.”

“That can wait, Dylan. I’m not sure Kristy can.”

“She’ll probably slam the door in my face.”

“You’re a big boy. Deal.”

Dylan sighed. He’d never taken Cassie’s so-called psychic abilities very seriously—she’d as much as admitted that she told her Tarot clients whatever she thought they wanted to hear—but there were times when her instincts struck too close to the bone for comfort.

He bent, kissed the top of Bonnie’s head and left.

Ten minutes later, he was knocking at Kristy’s door, still wondering what the hell he was going to say to explain being there in the first place.

She was wearing old pants, a man’s shirt and a lot of yellow paint when she opened the door.

And she’d been crying. Her eyes were puffy and her nostrils were red around the edges. Seeing Kristy in tears was devastating, but at least he wasn’t the cause of them this time—as far as he knew.

“Everything okay?” Dylan asked, stricken. Just call him the Wordmeister, he thought glumly. He’d always been able to talk his way into—or out of—any situation—unless that situation involved Kristy Madison.

“No,” she said. Her voice shook a little. Then she launched herself at him, wrapped both arms around his neck. “No!”

CHAPTER FOUR

DEAR GOD.

It should have been against the law to smell the way Kristy did—a tantalizing combination of rich grass after a heavy spring rain, leaves burning in autumn, talcum powder of some kind and paint thinner. For a precious moment, Dylan simply held her against him, breathed her in, closing his eyes tightly against the rush of emotion he felt.

Like most precious moments, that one was brief.

Kristy quickly bristled in his arms, pulled back, raised her chin and sniffled. The vulnerability in her cornflower-blue eyes turned to defiance.

“I apologize,” she said stiffly, as though he were a stranger she’d collided with in a crowded airport, not the first man who had ever made love to her. “I’ve just been under a little stress lately and—”

Dylan drew a long breath, let it out in a sigh as he closed Kristy’s front door behind him and hooked his thumbs through his belt loops. “Kristy,” he said. “This is me. Dylan. Something’s up with you, or you wouldn’t have practically tackled me on the threshold.”

Kristy gave an answering sigh, and her usually straight shoulders sagged in a way that tugged at a tender place in Dylan’s heart. “Come in,” she said, with about the same level of enthusiasm she might have shown a visiting terrorist wearing a suit of dynamite.

Dylan saw no reason to point out that he was already in—he simply followed Kristy through the house, expecting to wind up in the kitchen. When folks around the Springs had something to discuss, or just wanted to jaw awhile, they tended to congregate at the table, with the coffeepot and the refrigerator close at hand.

He’d visited the huge Victorian once or twice, with his dad, when Jake stopped by to collect an overdue paycheck from old man Turlow. The place had seemed dark and oppressive to him then, but Kristy had brightened it up considerably, with lace curtains and lots of pale yellow walls. The floors were gleaming oak, probably sanded to bare wood and then refinished.

That, too, would be Kristy’s doing.

She liked a lot of light and space—used to dream of living in the Turlow house one day.

It only went to show that some dreams came true, anyway.

A giant folding ladder stood just inside the kitchen doorway—Kristy ducked around it, Dylan walked between its runged legs.

“Coffee?” she asked. He saw the struggle in her face, but eventually, she couldn’t keep herself from adding, “You shouldn’t walk under ladders.”

“That’s a stupid superstition,” Dylan countered, with a twinkle. “And, yes, please, ma’am, I would like some coffee.”

“I wasn’t referring to the superstition,” Kristy insisted loftily, standing on her toes to fetch two mismatched mugs down from a cupboard. “Things could fall on your head, like a bucket of paint.”

“Still waiting for the sky to come crashing down, I see.” Dylan grinned, but tension twisted inside him like a screw turned too tight. He regretted those flippant words as soon as he saw them register in Kristy’s face. Behind that flimsy facade of bravery, she was crumbling.

Perhaps the sky was falling.

“Are you going to tell me what’s wrong,” he persisted, “or do I have to look it up on the Internet?”

A flush rose in her face. She poured coffee, carried the two cups to the table, and pulled back a chair with a practiced motion of one foot. “For Pete’s sake,” she said irritably, “sit down.”

“Not until you do,” Dylan replied. “I’m a gentleman.”

Kristy snorted at that, dropped into her chair. Added insult to injury by rolling her eyes once, for good measure.

Dylan took the chair next to hers, idly stroked the big white cat that immediately jumped into his lap.

“Sheriff Book was here a while ago,” Kristy said, elbow propped on the tabletop, her chin resting forlornly in her hand.

“Go on,” Dylan said.

Her eyes filled with fresh tears. “He thinks my father may have—may have killed someone.”

Stunned, Dylan set down the mug he’d just picked up and stared at Kristy, waiting for the punch line. Tim Madison, a murderer? Impossible. Kristy’s dad had been a soft-spoken, kindly man, hardworking and generous with what little he had.

Jake Creed, on the other hand, had been possessed of a legendary temper, and if Sheriff Book thought he’d offed some poor bastard, Dylan could have believed it. Although he didn’t tolerate criticism of Jake well, particularly when it came from his brothers, deep down he’d never had many illusions about the sort of man his father was.

“That’s crazy,” he said, finally.

Kristy sniffled again, tried a sip of her coffee, made a face and put it down again. “I know. But the county is going to dig up Sugarfoot’s grave. He tried to soften the blow, but Floyd clearly believes my father killed a man, probably by accident, and buried him with—with—”