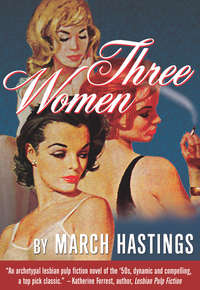

Three Women

“Do you like secrets? I wouldn’t have thought so.”

Paula didn’t know how to explain that this wasn’t a secret, exactly. It was more precious than a secret, this day. It was like a delicate infant that she didn’t want strangers to breathe on. She put the cup down on the floor and surrendered to a drowsiness that flowed upward from Byrne’s moving fingers.

“Byrne,” she said, “Byrne, tell me why I’m here.”

Abruptly the woman released Paula’s feet. She ran her fingers in the familiar gesture through the back of her hair and moved away from the couch. She stood looking down at Paula and Paula had the odd sensation of being measured for an unknown role.

“It’s not important,” Byrne said casually and brought a flaring match to meet her cigarette.

“Isn’t it?”

“No. You are simply growing up. Remember how important your breasts were when you first noticed them? Now they’re something you take for granted. They don’t rule you.”

Paula didn’t understand. But if Byrne said it wasn’t important, she would have to believe her. And yet a peculiar substance seemed to hang in the room, as though a voice were speaking not quite loud enough to be heard.

“Maybe I’m here because I want to paint,” she mused, wanting to capture and to understand. “I never realized that a woman’s body could be so inspiring.” She looked up at the picture. “Will you show me how?”

“Why not? I think there are some sketch pads in the bedroom,” Byrne answered with almost scientific directness, “if you’d like your first lesson now.”

Paula heard her rummaging through drawers. She wondered what kind of bed Byrne slept in. Did she sleep alone? The accomplishment of being here gave Paula courage. She got up and went to see what the room where Byrne spent her nights was like.

She leaned against the doorway and saw a strange-looking double bed. The mahogany headboard rose elaborately into carved angels and rosebuds. It didn’t look as if it should be Byrne’s bed. It seemed more the kind of thing that grandparents slept in. Byrne, reaching to a top shelf in the closet, did not notice Paula’s inspection. Nor did she see the girl approach the cigarette box on the dressing table.

Paula looked at it curiously. A woman’s photograph had been inserted in the center and covered by a curving glass that magnified the face. A face that pouted sadly, with delicate, unpainted lips trying a smile for the camera. The blonde hair, so blonde that it looked white, came in wisps of bangs over the forehead. The eyes seemed to dream of distant visions. Paula didn’t like the face. It held a sense of evil, and frightened her.

“Here it is,” Byrne said, stepping back from the closet and dusting off a spiral pad. “What’s the matter?”

“Who is this?” Paula’s voice was hardly audible.

“Oh, what do you care. Is there a pencil on the dresser top?”

But Paula couldn’t take her eyes away from the face. It held her with its almost innocent wickedness.

“Since you must know, she is the artist you so much admired. But don’t let it upset you. That picture was taken many years ago. She’s even older than I am.”

Paula whirled. “You’re not old. I wish you would stop saying that. You’re young and you’ll stay that way until the end — until the end of the earth. Only sick people get old. And poor miserable creatures who want to run away from what they are!”

Byrne examined her with mixed concern and enjoyment. Laugh lines wrinkled into the freckles across her nose. “One would never guess you had it in you,” she said. “Now will you forget that picture and let’s get down to business?”

For the first time, Paula realized how rude she was being. Her cheeks warmed and she dropped her glance to the carpet. “I’m sorry. I really shouldn’t have come in here.”

“Never mind. You’re a person who has to discover things the hard way. I’m only trying to make it a little easier for you if I can.”

“Well, I haven’t discovered a thing. I don’t understand at all why you’re so good to me.” She searched Byrne for an answer and found only those ocean-green eyes washing her with silence.

The woman firmly steered her out of the bedroom and back into the other world.

She set up a portable easel beside the bookshelf and stood the pad on it.

“Now, start with something simple. Try that percolator for instance.”

Obediently, Paula sketched the percolator. She felt no shyness about drawing. The old confidence from school reflected in her fingers. She drew the picture large with generous shading. Then she drew a cup and saucer with the percolator. Byrne stood behind her, offering no comment.

“Do I make your nervous if I watch?”

“Oh, no. I like you near me.” Intent on her work, Paula hardly knew the meaning of what she said. Page after page she filled with chairs and trees and fruit bowls.

Byrne finally said, “I wonder how well you sketch from life.”

“I never did.”

“Let’s try. I’ll be your model.”

Without embarrassment, as though it were the most everyday thing in the world, Byrne unbuttoned her shirt and dropped it to the floor. Paula watched, speechless, as she unhooked her bra and tossed it aside. The girl’s sight traveled over the smooth shoulders and down the arms. Byrne perched herself on the arm of the couch and said, “All right, draw.” There was no hint of challenge in her voice. It was matter of fact and sensible.

Paula clutched her pencil and stabbed grimly at the paper in front of her. The lines trembled as she drew them. She clenched her teeth, desperately trying to concentrate on the picture. Struggling for control, she managed neck and shoulders. With great detail, she drew the hands, the fingers crossed on the lap. She worked over the wrist bones half a dozen times to get them properly. Then up to the hollow in the throat. She examined her work and realized how ridiculous it looked. The middle was all blank. I can’t stare at her breasts like that, she thought. But I’ve got to. It means nothing. She expects me to do my best. Why am I acting like such a …

Taking a deep breath, she forced herself to look at that forbidden area. The pencil froze in her hand. Imploringly, she searched Byrne’s face, but the expression there remained impersonal. At last she got the pencil to the paper and sketched a few quick lines to indicate the feminine softness. Perspiration beaded across her forehead as she forced the pencil on and on over the page.

“All right,” she grunted. “I’ve finished now.”

“Good.” Byrne hopped off the couch and strolled over, not bothering to put on her shirt again.

Her nakedness loomed so close to Paula. The girl became dizzy and stepped backward. “Please,” she whispered, “put on your shirt.” She couldn’t bear looking at the body. But her eyes wouldn’t leave the incredible beauty of those twin shapes that to her seemed to be glowing in the lamplight.

Byrne didn’t move to get her clothing. “It’s only art,” she murmured. “If you want to draw, you can’t be so personal.”

Paula twisted away and stared at the wall. “Please,” she groaned. “Please.” She heard Byrne’s tongue click with impatience.

“All right,” she said after a moment’s pause. “I’m decent now. You can look.” Her voice mocked the girl.

Shame crept into Paula as she realized she had revealed an odd modesty. Normal women undressed before each other without concern, without embarrassment. She turned to face the woman and ask forgiveness for the strange demon that clawed inside her.

“Don’t apologize,” Byrne stopped her. “If you’d rather draw cups and saucers the rest of your life, you’re welcome to it.”

“Do you strip that way for everyone?” Paula asked.

“No. Of course not.”

“Did she see you naked?”

“Oh, my heavens! What do you want, a life history? Yes, Greta saw me naked. She diapered me and changed my bathing suit at the seashore. She slept in that bed, if you must know. And sometimes she still does, God help her. I told you I wasn’t young.”

Byrne got out the scotch and poured herself a stiff drink.

“Give me one, too,” Paula said.

“Not on your life. You’ll get drunk and bawl at me about how pure you thought all this was.”

“Pure? I’m not pure, either,” Paula lashed out. “I went to bed with Phil last night. It was the most miserable and disgusting thing that ever happened to me. I felt as if my insides were being torn to shreds. And that’s supposed to be love. Oh, I’m a slut just like everybody else. You don’t have to worry.” Shaken by her explosion of frankness, Paula grabbed the bottle and splashed whiskey into a cup.

“If you drink that,” Byrne said, her voice low, the words chiseled, “you’re never to come back here again.”

Paula stood glaring at her, the cup uncertainly poised.

Never to see Byrne again!

The demon put its fingers around her neck and pressed until she couldn’t swallow. Slowly, she lowered the cup. I’d rather die, she thought.

“That’s better,” Byrne relaxed. “Now come over here and sit down.”

Without question, Paula went. There was nothing she would not do if only Byrne could be pleased with her again.

“You draw quite well.” Byrne resumed her teaching manner. “But it’s obvious that you need lots of practice. Do you think you can control yourself for a couple of weeks until you master the fundamentals?”

“Yes,” Paula said, not knowing whether she could or not. “I can do anything you think is necessary.”

“Good. Now, you’re too upset to go any farther today. Suppose you come back Tuesday evening. I’ll have better supplies by then.”

Paula didn’t want to leave, but she knew the woman had other things to do than dawdle with her. Regretfully, she put on her coat.

“Here’s cab fare home.” Byrne tilted Paula’s chin. “And don’t think about this too much. If I didn’t like you, I wouldn’t take the trouble.”

Paula felt a beaming smile leap to her face. Byrne pressed a five dollar bill into her hand and pushed her out the door.

She skipped dizzily up the street. She likes me! She likes me no matter what I did!

At the corner of Fifth Avenue, she hailed a cab. Once inside, she crossed her legs and tried to sit like a lady. It wasn’t often that she could ride like this. What wonderful, marvelous things would Byrne make possible for her? If she could only return some of the joy, some of the gratefulness that filled her. She resolved that anything Byrne asked her to do — sketch her nude, anything — she would do it if it took all the courage she could muster. She would please Byrne. She must please Byrne. Nothing in life was so important as Byrne’s approval.

The cabbie changed the five dollars and raised his eyebrows when she told him to keep the change.

3

Paula burst into the apartment and ran to her room, anxious to be alone with her dreaming. It was hardly four o’clock and the smell of roast chicken reminded her that she hadn’t eaten all day.

Her mother came into her room and waited until Paula had taken off her things.

“Phil was here,” she said. “He waited for you an hour and a half.” Her voice held a question.

“Didn’t you tell him I was out?”

“Yes. But he expected that you would be back soon.”

The idea of Phil returned to Paula like an old shoe, suddenly found. She wished he would stay, like an old shoe, in the closet and wait until she was ready for him.

“Maybe you’d better call him,” her mother offered. She was wearing an apron over the Sunday dress. The family hadn’t gone out today. Uncomfortably, Paula supposed they were worrying about her.

“All right, I’ll call him. After dinner.” She didn’t want to speak to Phil. He would ask where she’d been. Now that he had proposed, he probably felt a right to question her. Could she put him off without making him angry? Perhaps. But not without hurting him. Oh, she seemed to be hurting everybody. Ma and Pa this afternoon and now Phil.

“I only spent a harmless afternoon,” Paula explained, “away from troubles. There’s nothing wrong with that, is there?”

Her mother looked at the pencil smudges on her fingers. “If you’re feeling better, I’m glad you went wherever it was.”

“I’m feeling fine,” Paula almost sang. If only I could tell you about it! The faint odor of pomade lingered as her mother went to light the stove under the cold chicken.

Why can’t I tell her, she thought. What’s wrong with what I’ve done? But she didn’t want to speak about her dear Byrne. The thought of Byrne in this apartment didn’t fit. She wasn’t the kind of person you discussed in cold water flats. Not even to your mother. Byrne was meant for dreaming late at night. Late at night in the dark and all alone.

She changed into a pair of corduroy slacks and looked at herself in the bubbles of the mirror that framed the old dressing table. She didn’t have those trim lines. Her hips were too rounded, her waist too small. She searched out one of Mike’s old shirts and jammed the tails into her trousers. Then she rolled up the too-long sleeves and once more examined her reflection. She just wasn’t impressive.

The mound of mashed potatoes and gravy added strength to her unwound nerves. Halfway through the meal the phone rang. Pa was taking a nap in the bedroom. She and her mother looked at each other.

“If it’s Phil, tell him I’m eating and he can pick me up at seven.”

Paula knew she would have to see him. No matter how much she didn’t want to, it was better to get this over with soon. Or he would be calling and wondering and having fits.

“Don’t you want to talk to him?” Ma tried to cover her perplexity.

“Not just now.” Paula attended to the chicken.

She listened to her mother deliver the message while she poured vinegar into the almost empty bottle of ketchup.

“He’ll be over,” her mother said, setting a dish of fruit salad on the table.

Well, she didn’t have to think about Phil until he got here. Some excuse would come to her by then. She didn’t care to lie to him. But he would never understand the truth. What was the truth? She hardly knew herself. All she knew was that this afternoon was her own private possession.

Phil arrived almost promptly at seven, his features muddled with concern. She motioned him to a chair and he sat on it sideways because his long legs wouldn’t fit comfortably under the table. She could tell he wanted to talk to her earnestly but he made polite conversation for the sake of her mother.

At last he said, “Want to catch a movie?”

Her eyesight was strained from the afternoon’s sketching, but she agreed just to get them out of the house.

They didn’t go to the movies, of course. He took her to Jack’s place.

“Look,” he said, when they had closed the door, “I didn’t do anything — I mean, it was all right?”

She considered the appeal in his eyes, then the yellow rumpled bedsheets. The musty smell of stale furniture and cat hairs over everything curdled her stomach.

“Sure,” she said. “It was all right.”

The sound of Whitey scratching in the kitty litter filled the silence. A pot of left-over spaghetti filled with water sat in the wash basin. “No, it wasn’t all right,” she blurted. “It’s miserable here and I hate it. Why do we always have to come to this place? Why couldn’t you have waited until we had somewhere decent?”

He looked at her with confusion. She saw the irritation growing within him and the line of his mouth tightened. “You’re a strange girl today. I can’t believe it was all my fault.”

Immediately she felt sorry for him. After all, he was battling against something he didn’t even know about. She couldn’t help him. She could hardly help herself, let alone Phil.

“If I’m so strange, then just leave me be.” The hardness in Paula’s voice covered her own groping to understand.

“Oh, honey, why don’t you come off it? That was bound to happen sooner or later. What difference could it make that we didn’t have a license for it last night?”

There was no point in arguing. How can you explain to a man, still dear to you, he has suddenly been replaced?

“The fact is, Phil, I’m not sure that I’m ready to get married just yet.”

“And why not? You seemed plenty eager these past couple of months.”

That was the truth and it slapped her. She went to open a window, thinking some fresh air might chase the musty smell. She opened the window and thought: If I jumped out all this mess would be over. She stood looking down the narrow alleyway at the empty clotheslines tangled from the wind.

“I know I owe you an explanation, but the truth is I haven’t any.”

“Sure, you haven’t. You don’t know what in hell you’re talking about. When they say women are addle-brained, I have an idea this is exactly what they mean.”

He was being nasty. But it was nastiness out of desperation, she knew. He had to fight back against this unknown enemy. If he fought clumsily, it was nonetheless brave.

“Phil, I love you. I just need time to work something over in my mind. Will you try to be patient and not force me?”

“Patient? God save us all! Here I am planning for our marriage next month and you say to be patient. Is that what you call love?”

“All right, then,” she challenged. A stabbing frustration and restlessness shot through. “Call it off. Go away and leave me alone. I don’t want to see you, Phil. I want to be alone. Do you hear me? Alone!”

He grabbed her away from the window and pulled her beside him against the wall. “You’re nuts,” his voice rasped. “Stark, raving nuts.”

She struggled, pounding his chest with clenched fists. “Leave me be!” she shouted. “Leave me be!”

He held her fast. “You’re going to calm down and straighten out.” Grabbing her wrists, he held them fast behind her back. “Honey, you’re hysterical.”

Twisting and turning, she tried to free herself from his grasp. Biting at his arm, she caught the material of his shirt between her teeth and ripped it.

His bulk was too much for her. Panting, she let her body collapse. For a moment he stood supporting the weight of her in his arms. Then slowly, she slipped to the floor and collapsed at his feet. He kneeled beside her, not knowing what to do. She crawled over, put her head in his lap and sobbed wretchedly.

Clumsily, he stroked her hair. “It’s all right, honey. If you want to be alone, it’s okay.” His voice was heavy with sadness. “Just don’t get lost,” he said. “We need each other too much.”

When he brought her home, he didn’t try to kiss her. He sort of patted her shoulder and ran off down the steps. She listened to the disappearing jingle of his house keys.

Paula was grateful for Monday. Getting up and yelling at Mike to hurry up out of the bathroom kept her from thinking for the moment about the strange state of affairs in her life.

The rush hour crowds carried her down the steps to the subway where she stood on line to buy a week’s supply of tokens.

Her office friends greeted her and chatted about their dates as if this had been a weekend like any other. Paula felt as though she had been away for a hundred years until her desk, her typewriter, the small switchboard with its tails and plugs hypnotized her back into the meaningless routine.

At five o’clock she looked for Phil’s car but it wasn’t there. She waited ten minutes. He didn’t show up. She realized with huge relief that he really was going to let her alone for awhile. Poor guy. She didn’t like herself very much for yesterday’s scene, but as she tried to think of Phil, the picture of him faded, replaced by the image of that shirtless body, the tantalizing curves of warm flesh, coldly posed for sketching.

When she got home, the place was jammed with Mike’s friends making a pretense of doing homework. Pa hadn’t arrived yet. She helped set the table and prepared a place for him, even though she didn’t know whether or not he would be in any condition to eat.

Ma said, “Did you have a good day?”

“Like every other,” Paula answered. Then she said, “Ma, did you think when you got married that this was the way life was going to be?”

Her mother wiped her hands on the apron and studied the worn wedding ring on her finger. “That’s a funny question, my dear. In those days, you know, we didn’t think about how it would all turn out. We just took our chances. We trusted the man to do what he should do, and so would we.” She always spoke in terms of “we” because she had seven sisters.

“But didn’t you have any imagination? Didn’t you wonder whether the future was going to be bright or not?”

“Maybe old-fashioned people take it for granted the future will be bright. I guess I don’t know, dear.”

Paula knew her mother wasn’t trying to chide her. And she was being discreet enough not to ask why Phil hadn’t brought her home. He always came upstairs for a short visit. Her mother enjoyed the company. She liked Phil. And Paula could see that her own sudden hesitance about marrying him was a disappointment.

The boys were fighting so loudly over the verb of a sentence that nobody heard Pa come in. He stumbled into the kitchen and fell heavily on the table, his face yellow with a frightening pallor.

“Harry!” Her mother ran to him. He fell forward, upsetting the empty glasses, and lay with his cheek against the oilcloth.

Paula ran to the phone to call the doctor. Her hands trembled as they dialed numbers.

She cleared the boys out and sent Mike with them. Her father lay at the table, retching with spasms, speechless in pain. She and her mother tried to move him to the bed but he couldn’t make it.

The doctor arrived, and the three of them managed to get the old man into bed. After the examination, the doctor put his stethoscope in his bag and filled out a prescription.

“It’s nothing to worry about, Mrs. Temple. He’ll have to stay in bed for a couple of weeks. No alcohol, of course. Plenty of tea and broth and rest. This will keep him quiet through the night. I’ll drop by tomorrow.”

Paula gave him the five dollar visiting fee, regretting the generous tip to the cabbie yesterday. Every penny she earned was tightly accounted for. Doctor bills were things to be dreaded. They could cut a hole into your life that sometimes took years to repair. Nothing to worry about, the doctor said. Well, there was plenty to worry about.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги