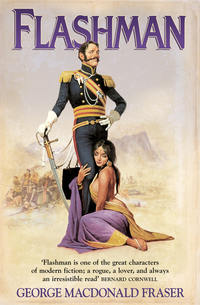

Flashman

‘My wee lamb!’ he kept snuffling. ‘My bonny wee lamb!’

His wee lamb, I may say, looked entrancing, and no more moved than if she had just been out choosing a pair of gloves, rather than getting a husband – she had taken the whole thing without a murmur, neither happy nor sorry, apparently, which piqued me a little.

Anyway, her father slobbered over her, but when he turned to me he just let out a great hollow groan, and gave place to his wife. At that I whipped up the horses, and away we went.

For the life of me I cannot remember where the honeymoon was spent – at some rented cottage on the coast, I remember, but the name has gone – and it was lively enough. Elspeth knew nothing, but it seemed that the only thing that brought her out of her usual serene lethargy was a man in bed with her. She was a more than willing playmate, and I taught her a few of Josette’s tricks, which she picked up so readily that by the time we came back to Paisley I was worn out.

And there the shock was waiting: it hit me harder, I think, than anything had in my life. When I opened the letter and read it, I couldn’t speak at first; I had to read it again and again before it made sense.

‘Lord Cardigan [it read] has learned of the marriage contracted lately by Mr Flashman of this regiment, and Miss Morrison, of Glasgow. In view of this marriage, his lordship feels that Mr Flashman will not wish to continue to serve with the 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s), but that he will wish either to resign or to transfer to another regiment.’

That was all. It was signed ‘Jones’ – Cardigan’s toady.

What I said I don’t recall, but it brought Elspeth to my side. She slid her arms round my waist and asked what was the matter.

‘All hell’s the matter,’ I said. ‘I must go to London at once.’

At this she raised a cry of delight, and babbled with excitement about seeing the great sights, and society, and having a place in town, and meeting my father – God help us – and a great deal more drivel. I was too sick to heed her, and she never seemed to notice me as I sat down among the boxes and trunks that had been brought in from the coach to our bedroom. I remember I damned her at one point for a fool and told her to hold her tongue, which silenced her for a minute; but then she started off again, and was debating whether she should have a French maid or an English one.

I was in a furious rage all the way south, and impatient to get to Cardigan. I knew what it was all about – the bloody fool had read of the marriage and decided that Elspeth was not ‘suitable’ for one of his officers. It will sound ridiculous to you, perhaps, but it was so in those days in a regiment like the 11th. Society daughters were all very well, but anything that smacked of trade or the middle classes was anathema to his lofty lordship. Well, I was not going to have his nose turned up at me, as he would find. So I thought, in my youthful folly.

I took Elspeth home first. I had written to my father while we were on honeymoon, and had had a letter back saying: ‘Who is the unfortunate chit, for God’s sake? Does she know what she has got?’ So all was well enough in its way on that front. And when we arrived there who should be the first person we met in the hall but Judy, dressed for riding. She gave me a tongue-in-the-cheek smile as soon as she saw Elspeth – the clever bitch probably guessed what lay behind the marriage – but I got some of my own back by my introduction.

‘Elspeth,’ I said, ‘this is Judy, my father’s tart.’

That brought the colour into her face, and I left them to get acquainted while I looked for the guv’nor. He was out, as usual, so I went straight off in search of Cardigan, and found him at his town house. At first he wouldn’t see me, when I sent up my card, but I pushed his footman out of the way and went up anyway.

It should have been a stormy interview, with high words flying, but it wasn’t. Just the sight of him, in his morning coat, looking as though he had just been inspecting God on parade, took the wind out of me. When he had demanded to know, in his coldest way, why I intruded on him, I stuttered out my question: why was he sending me out of the regiment?

‘Because of your marriage, Fwashman,’ says he. ‘You must have known very well what the consequences would be. It is quite unacceptable, you know. The lady, I have no doubt, is an excellent young woman, but she is – nobody. In these circumstances your resignation is imperative.’

‘But she is respectable, my lord,’ I said. ‘I assure you she is from an excellent family; her father—’

‘Owns a factory,’ he cut in. ‘Haw-haw. It will not do. My dear sir, did you not think of your position? Of the wegiment? Could I answer, sir, if I were asked: “And who is Mr Fwashman’s wife?” “Oh, her father is a Gwasgow weaver, don’t you know?”

‘But it will ruin me!’ I could have wept at the pure, blockheaded snobbery of the man. ‘Where can I go? What regiment will take me if I’m kicked out of the 11th?’

‘You are not being kicked out, Fwashman,’ he said, and was being positively kindly. ‘You are wesigning. A very different thing. Haw-haw. You are twansferring. There is no difficulty. I wike you, Fwashman; indeed, I had hopes of you, but you have destwoyed them with your foolishness. Indeed, I should be extwemely angwy. But I shall help in your awwangements: I have infwuence at the Horse Guards, you know.’

‘Where am I to go?’ I demanded miserably.

‘I have given thought to it, let me tell you. It would be impwoper to twansfer to another wegiment at home; it will be best if you go overseas, I think. To India. Yes—’

‘India?’ I stared at him in horror.

‘Yes, indeed. There are caweers to be made there, don’t you know? A few years’ service there, and the matter of your wesigning fwom my wegiment will be forgotten. You can come home and be gazetted to some other command.’

He was so bland, so sure, that there was nothing to say. I knew what he thought of me now: I had shown myself in his eyes no better than the Indian officers whom he despised. Oh, he was being kind enough, in his way; there were ‘caweers’ in India, all right, for the soldier who could get nothing better – and who survived the fevers and the heat and the plague and the hostile natives. At that moment I was at my lowest; the pale, haughty face and the soft voice seemed to fade away before me; all I was conscious of was a sullen anger, and a deep resolve that wherever I went, it would not be India – not for a thousand Cardigans.

‘So you won’t, hey?’ said my father, when I told him.

‘I’m damned if I do,’ I said.

‘You’re damned if you don’t,’ chuckled he, very amused. ‘What else will you do, d’you suppose?’

‘Sell out,’ says I.

‘Not a bit of it,’ says he. ‘I’ve bought your colours, and by God, you’ll wear ’em.’

‘You can’t make me.’

‘True enough. But the day you hand them back, on that day the devil a penny you’ll get out of me. How will you live, eh? And with a wife to support, bigad? No, no, Harry, you’ve called the tune, and you can pay the piper.’

‘You mean I’m to go?’

‘Of course you’ll go. Look you, my son, and possibly my heir, I’ll tell you how it is. You’re a wastrel and a bad lot – oh, I daresay it’s my fault, among others, but that’s by the way. My father was a bad lot, too, but I grew up some kind of man. You might, too, for all I know. But I’m certain sure you won’t do it here. You might do it by reaping the consequences of your own lunacy – and that means India. D’you follow me?’

‘But Elspeth,’ I said. ‘You know it’s no country for a woman.’

‘Then don’t take her. Not for the first year, in any event, until you’ve settled down a bit. Nice chit, she is. And don’t make piteous eyes at me, sir; you can do without her a while – by all accounts there are women in India, and you can be as beastly as you please.’

‘It’s not fair!’ I shouted.

‘Not fair! Well, well, this is one lesson you’re learning. Nothing’s fair, you young fool. And don’t blubber about not wanting to go and leave her – she’ll be safe enough here.’

‘With you and Judy, I suppose?’

‘With me and Judy,’ says he, very softly. ‘And I’m not sure that the company of a rake and a harlot won’t be better for her than yours.’

That was how I came to leave for India; how the foundation was laid of a splendid military career. I felt myself damnably ill-used, and if I had had the courage I would have told my father to go to the devil. But he had me, and he knew it. Even if it hadn’t been for the money part of it, I couldn’t have stood up to him, as I hadn’t been able to stand up to Cardigan. I hated them both, then. I came to think better of Cardigan, later, for in his arrogant, pigheaded, snobbish way he was trying to be decent to me, but my father I never forgave. He was playing the swine, and he knew it, and found it amusing at my expense. But what really poisoned me against him was that he didn’t believe I cared a button for Elspeth.

There may be better countries for a soldier to serve in than India, but I haven’t seen them. You may hear the greenhorns talk about heat and flies and filth and the natives and the diseases; the first three you must get accustomed to, the fifth you must avoid – which you can do, with a little common sense – and as for the natives, well, where else will you get such a docile humble set of slaves? I liked them better than the Scots, anyhow; their language was easier to understand.

And if these things were meant to be drawbacks, there was the other side. In India there was power – the power of the white man over the black – and power is a fine thing to have. Then there was ease, and time for any amount of sport, and good company, and none of the restrictions of home. You could live as you pleased, and lord it among the niggers, and if you were well-off and properly connected, as I was, there was the social life among the best folk who clustered round the Governor-General. And there were as many women as you could wish for.

There was money to be had, too, if you were lucky in your campaigns and knew how to look for it. In my whole service I never made half as much in pay as I got from India in loot – but that is another story.

I knew nothing of this when we dropped anchor in the Hooghly, off Calcutta, and I looked at the red river banks and sweated in the boiling sun, and smelt the stink, and wished I was in hell rather than here. It had been a damnable four-months voyage on board the crowded and sweltering Indiaman, with no amusement of any kind, and I was prepared to find India no better.

I was to join one of the Company’s native lancer regiments9 in the Benares District, but I never did. Army inefficiency kept me kicking my heels in Calcutta for several weeks before the appropriate orders came through, and by that time I had taken fortune by the foreskin, in my own way.

In the first place, I messed at the Fort with the artillery officers in the native service, who were a poor lot, and whose messing would have sickened a pig. The food was bad to begin with, and by the time the black cooks had finished with it you would hardly have fed it to a jackal.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов