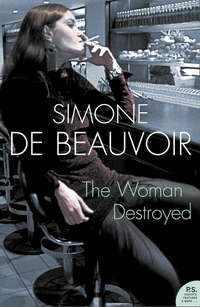

The Woman Destroyed

‘You’re not going to stand up for him.’

‘I’m trying to find an explanation.’

‘No explanation will ever convince me. I shall never see him again. And I don’t want you to see him, either.’

‘Make no mistake about this. I disapprove of him. I disapprove very strongly. But I shall see him again. So will you.’

‘No I shan’t. And if you let me down, after what he said to me on the telephone, I’ll take it more unkindly—I’ll resent it more than I have ever resented anything you’ve done all my life. Don’t talk to me about him any more.’

But we could not talk of anything else, either. We had dinner almost in silence, very quickly, and then each of us took up a book. I felt bitter ill-will against Irene, against André, against the world in general. ‘We certainly have our share of responsibility.’ How trifling it was to look for reasons and excuses. ‘Your senile obstinacy’: he had shouted those words at me. I had been so certain of his love for us, for me: in actual fact I did not amount to anything much—I was nothing to him; just some old object to be filed away among the minor details. All I had to do was to file him away in the same fashion. The whole night through I choked with resentment. The next morning, as soon as André was gone, I went into Philippe’s room, tore up the old letters, flung out the old papers, filled one suitcase with his books, piled his pull-over, pyjamas and everything that was left in the cupboards into another. Looking at the bare shelves I felt my eyes fill with tears. So many moving, overwhelming memories rose up within me. I wrung their necks for them. He had left me, betrayed me, jeered at me, insulted me. I should never forgive him.

Two days went by without our mentioning Philippe. The third morning, as we were looking at our post, I said to André, ‘A letter from Philippe.’

‘I imagine he is saying he’s sorry.’

‘He’s wasting his time. I shan’t read it.’

‘Oh, but have a look at it, though. You know how hard he finds it to make the first step. Give him a chance.’

‘Certainly not.’ I folded the letter, put it into an envelope and wrote Philippe’s address. ‘Please post that for me.’

I had always given in too easily to his charming smiles and his pretty ways. I should not give in this time.

Two days later, early in the afternoon, Irène rang the bell. ‘I’d like to talk to you for five minutes.’

A very simple little dress, bare arms, hair down her back: she looked like a girl, very young, dewy and shy. I had never yet seen her in that particular role. I let her in. She had come to plead for Philippe, of course. The sending back of his letter had grieved him dreadfully. He was sorry for what he had said to me on the telephone; but he did not mean a word of it; but I knew his nature—he lost his temper very quickly and then he would say anything at all, but it was really only so much hot air. He absolutely had to have it out with me.

‘Why didn’t he come himself?’

‘He was afraid you would slam the door on him.’

‘And that’s just what I should have done. I don’t want to see him again. Full stop. The end.’

She persisted. He could not bear my bong cross with him: he had never imagined I should take things so much to heart.

‘In that case he must have turned into a half-wit: he can go to hell.’

‘But you don’t realize. Papa has worked a miracle for him: a post like this, at his age, is something absolutely extraordinary. You can’t ask him to sacrifice his future for you.’

‘He had a future, a dean one, true to his own ideas.’

‘I beg your pardon—true to your ideas. He has developed.’

‘He will go on developing: it’s a tune we all know. He will make his opinions chime with his interests. For the moment he is up to his middle in bad faith—his only idea is to succeed. He is betraying himself and he knows it; that is what is so tenth-rate,’ I said passionately.

Irène gave me a dirty look. ‘I imagine your own life has always been perfect, and so that allows you to judge everybody else from a great height.’

I stiffened. ‘I have always tried to be honest. I wanted Philippe to be the same. I am sorry that you should have turned him from that course.’

She burst out laughing. ‘Anyone would think he had become a burglar, or a coiner.’

‘For a man of his convictions, I do not consider his an honourable choice.’

Irène stood up. ‘But after all it is strange, this high moral stand of yours,’ she said slowly. ‘His father is more committed, politically, than you; and he has not broken with Philippe. Whereas you …’

I interrupted her. ‘He has not broken … You mean they’ve seen one another?’

‘I don’t know,’ she replied quickly. ‘I know he never spoke of breaking when Philippe told him about his decision.’

‘That was before the phone call. What about since?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know who Philippe sees and who he doesn’t?’

Looking stubborn she said, ‘No.’

‘All right. It doesn’t matter,’ I said.

I saw her as far as the door. I turned our last exchanges over in my mind. Had she cut herself short on purpose—a cunning stroke—or was it a blunder? At all events my mind was made up. Almost made up. Not quite enough for it to find an outlet in rage. Just enough for me to be choked with distress and anxiety.

As soon as André came in I went for him. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you had seen Philippe again?’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Irène. She came to ask me why I didn’t see him, since you did.’

‘I warned you I should see him again.’

‘I warned you that I should resent it most bitterly. It was you who persuaded him to write to me.’

‘No: not really.’

‘It certainly was. Oh, you had fun with me, all right: “You know how hard it is for him to make the first step.” And it was you who had made it! Secretly.’

‘With regard to you, he did make the first step.’

‘Urged on by you. You plotted together behind my back. You treated me like a child—an invalid. You had no right to do so.’

Suddenly there was red smoke in my brain, a red mist in front of my eyes, something red shouting out in my throat. I am used to my rages against Philippe; I know myself when I am in one of them. But when it happens (and it is rare, very rare) that I grow furious with André, it is a hurricane that carries me away thousands of miles from him and from myself, into a desert that is both scorching and freezing cold.

‘You have never lied to me before! This is the first time.’

‘Let us agree that I was in the wrong.’

‘Wrong to see Philippe again, wrong to plot against me with him and Irène, wrong to make a fool of me, to lie to me. That’s very far in the wrong.’

‘Listen … will you listen to me quietly?’

‘No. I don’t want to talk to you any more; I don’t want to see you any more. I must be by myself: I am going out for a walk.’

‘Go for a walk then, and try to calm yourself down,’ he said curtly.

I set off through the streets and I walked as I often used to do when I wanted to calm my fears or rages or to get rid of mental images. Only I am not twenty any more, nor even fifty, and weariness came over me very soon. I went into a café and drank a glass of wine, my eyes hinting in the cruel glare of the neon. Philippe: it was all over. Married, a deserter to the other side. André was all I had left and there it was—I did not have him either. I had supposed that each of us could see right into the other, that we were united, linked to one another like Siamese twins. He had cast himself off from me, lied to me; and here I was on this café bench, alone. I continually called his face, his voice to mind, and I blew on the fire of the furious resentment that was burning me up. It was like one of those illnesses in which you manufacture your own suffering—every breath tears your lungs to pieces, and yet you are forced to breathe.

I left, and I set off again, walking. So what now? I asked myself in a daze. We were not going to part. Each of us alone, we should go on living side by side. I should bury my grievances, then, these grievances that I did not want to forget. The notion that one day my anger would have left me made it far worse.

When I got home I found a note on the table: ‘I have gone to the cinema.’ I opened our bedroom door. There were André’s pyjamas on the bed, a packet of tobacco and his blood-pressure medicines on the bedside table. For a moment he existed—a heart-piercing existence—as though he had been taken far from me by illness or exile and I were seeing him again in these forgotten, scattered objects. Tears came into my eyes. I took a sleeping-pill; I went to bed.

When I woke up in the morning he was asleep, curled in that odd position with one hand against the wall. I looked away. No impulse towards him at all. My heart was as dreary and frigid as a deconsecrated church in which there is no longer the least warm flicker of a lamp. The slippers and the pipe no longer moved me; they no longer called to mind a beloved person far away; they were merely an extension of that stranger who lived under the same roof as myself. Dreadful anomaly of the anger that is born of love and that murders love.

I did not speak to him. While he was drinking his tea in the library I stayed in my room. Before leaving he called, ‘You don’t want to have it out?’

‘No.’

There was nothing to ‘have out’. Words would shatter against this anger and pain, this hardness in my heart.

All day long I thought of André, and from time to time there was something that flickered in my brain. Like having been hit on the head, when one’s sight is disordered and one sees two different images of the world at different weights, without being able to make out which is above and which below. The two pictures I had, of the past André and the present André, did not coincide. There was an error somewhere. This present moment was a lie: it was not we who were concerned—not André, nor I: the whole thing was happening in another place. Or else the past was an illusion, and I had been completely wrong about André. Neither the one nor the other, I said to myself when I could see clearly again. The truth was that he had changed. Aged. He no longer attributed the same importance to things. Formerly he would have found Philippe’s behaviour utterly revolting: now he did no more than disapprove. He would not have plotted behind my back; he would not have lied to me. His sensitivity and his moral values had lost their fine edge. Will he follow this tendency? More and more indifferent … I can’t bear it. This sluggishness of the heart is called indulgence and wisdom: in fact it is death settling down within you. Not yet: not now.

That day the first criticism of my book appealed. Lantier accused me of going over the same ground again and again. He’s an old fool and he loathes me; I ought never to have let myself feel it But in my exacerbated mood I did grow vexed. I should have liked to talk to André about it, but that would have meant making peace with him: I did not want to.

‘I’ve shut up the laboratory,’ he said that evening, with a pleasant smile. ‘We can leave for Villeneuve and Italy whatever day you like.’

‘We had decided to spend this month in Paris,’ I answered shortly.

‘You might have changed your mind.’

‘I have not done so.’

André’s face darkened. ‘Are you going to go on sulking for long?’

‘I’m afraid I am.’

‘Well, you’re in the wrong. It is out of proportion to what has happened.’

‘Everyone has his own standards.’

‘Yours are astray. It’s always the same with you. Out of optimism or systematic obstinacy you hide the truth from yourself and when it is forced upon you you either collapse or else you explode. What you can’t bear—and of coarse I bear the brunt of it—is that you had too high an opinion of Philippe.’

‘You always had too low a one.’

‘No. It was merely that I never had much in the way of illusions about his abilities or his character. Yet even so I thought too highly of him.’

‘A child is not something you can evaluate like an experiment in the laboratory. He turns into what his parents make him. You backed him to lose, and that was no help to him at all.’

‘And you always back to win. You’re free to do so. But only if you can take it when you lose. And you can’t take it. You always try to get out of paying; you fly into a rage, you accuse other people right and left—anything at all not to own yourself in the wrong.’

‘Believing in someone is not being in the wrong.’

‘Pigs will fly the day you admit you were mistaken.’

I know. When I was young I was perpetually in the wrong and it was so difficult for me ever to be in the right that now I am very reluctant ever to blame myself. But I was in no mood to acknowledge it. I grasped the whisky bottle. ‘Unbelievable! You as prosecuting counsel against me!’

I filled a glass and emptied it in one gulp. André’s face, André’s voice: the same man, another; beloved, hated; this anomaly went down inside my body. My sinews, my muscles contracted in a tetanic convulsion.

‘From the very beginning you refused to discuss it calmly. Instead of that you have been swooning about all over the place … And now you’re going to get drunk? It’s grotesque,’ he said, as I began my second glass.

‘I shall get drunk if I want. It’s nothing to do with you: leave me alone.’

I carried the bottle into my room. I settled in bed with a spy-story but I could not read. Philippe. I had been so wholly taken up with my fury against André that his image had faded a little. Suddenly he was there smiling at me with unbearable sweetnesss through the swimming of the whisky. Too high an opinion of him: no. I had loved him for his weaknesses: if he had been less temperamental and less casual he would have needed me less. He would never have been so adorably tender if he had nothing to beg forgiveness for. Our reconciliations, tears, kisses. But in those days it was only a question of peccadilloes. Now it was something quite different. I swallowed a brimming glass of whisky, the walls began to turn, and I sank right down.

The light made its way through my eyelids. I kept them closed. My head was heavy: I was deathly sad. I could not remember my dreams. I had sunk down into black depths—liquid and stifling, like diesel-oil—and now, this morning, I was only just coming to the surface. I opened my eyes. André was sitting in an armchair at the foot of the bed, watching me with a smile. ‘My dear, we can’t go on like this.’

It was he, the past, the present André, the same man; I acknowledged it. But there was still that iron bar in my chest. My lips trembled. Stiffen even more, sink to the bottom, drown myself in the depths of loneliness and the night. Or try to catch this outstretched hand. He was talking in that even, calming voice I love. He admitted that he had been wrong. But it was for my sake that he had spoken to Philippe. He knew we were both so miserable that he had determined to step in right away, before our break could become definitive.

‘You are always so gay and alive, and you have no idea how wretched it made me to see you eating your heart out! I quite understand that at the time you were furious with me. But don’t forget what we are for one another: you mustn’t hold it against me for ever.’

I gave a weak smile; he came close and put an arm round my shoulders. I clung to him and wept quietly. The warm physical pleasure of tears running down my cheek. What a relief! It is so tiring to hate someone you love.

‘I know why I lied to you,’ he said to me a little later. ‘Because I’m growing old. I knew that telling you the truth would mean a scene: that would never have held me back once, but now the idea of a quarrel makes me feel weary. I took a short cut.’

‘Does that mean you are going to lie to me more and more?’

‘No, I promise you. And in any case I shan’t see Philippe often: we haven’t much to say to one another.’

‘Quarrels make you feel tired: but you bawled me out very thoroughly yesterday evening, for all that.’

‘I can’t bear it when you sulk. It’s much better to shout and scream.’

I smiled at him. ‘Maybe you’re right. We had to get out of it.’

He took me by the shoulders. ‘We are out of it, really out of it? You aren’t cross with me any more?’

‘Not any more at all. It’s over and done with.’

It was over: we were friends again. But had we said everything we had to say to one another? I had not, at all events. There was still something that rankled—the way André just gave in to old age. I did not want to talk about it to him now: the sky had to be quite clear again first. And what about him? Had he any mental reservations? Was he serious in blaming me for what he called my systematically stubborn optimism? The storm had been too short to change anything between us: but Was it not a sign that for some time past—since when?—something had in fact been imperceptibly changing?

Something has changed, I said to myself as we drove down the motorway at ninety miles an hour. I was sitting next to André; our eyes saw the same road and the same sky; but between us, invisible and intangible, there was an insulating layer. Was he aware of it? Yes, certainly he was. The reason why he had suggested this drive was that he hoped it might bring to life the memory of other drives in the past and so bring us wholly together again: it was not like them at all, however, because he did not look forward to deriving the least pleasure from it. I ought to have been grateful for his kindness: but I was not. I was hurt by his indifference. I had felt it so distinctly that I had almost refused, but he would have taken the refusal as a mark of ill-will. What was happening to us? There had been quarrels in our life, but always over serious matters—over the bringing up of Philippe, for example. They were genuine conflicts that we resolved violently, but quickly and for good. This time it had been a great whirling of fog, or smoke without fire; and because of its very vagueness two days had not quite cleared it away. And then again, in former times bed was the place for our stormy reconciliations. Trifling grievances were utterly burnt away in amorous delight, and we found ourselves together again, happy and renewed. Now we were deprived of that resource.

I saw the signpost; I stared and stared again. ‘What? Already? We only set off twenty minutes ago.’

‘I drove fast,’ said André.

Milly. When Mama used to take us to see Grandmama, what an expedition it was! It was the country, vast golden wheat-fields, and we picked poppies at their edges. That remote village was now nearer to Paris than Neuilly or Auteuil had been in Balzac’s day.

André found it hard to park the car, for it was market-day—swarms of cars and pedestrians. I recognized the old covered market, the Lion d’Or, the houses and their faded tiles. But the square was completely changed by the stalls that were set up in it. The plastic pots and toys, the millinery, tinned food, scent and the jewellery were in no way reminiscent of the old village fairs. It was Monoprix or Inno shops spread out in the open air. Glass. doors and walls: a big glittering stationery shop, filled with books and magazines with shiny covers. Grandmama’s house, once a little outside the village, had been replaced by a five-storey building, and it was now right inside the town.

‘Would you like a drink?’

‘Oh, no!’ I said. ‘It’s not my Milly any more.’ Nothing is the same any more, and that’s certain: neither Milly, nor Philippe, nor André. Am I?

‘Twenty minutes to reach Milly is miraculous,’ I said as we got back into the car. ‘Only it’s not Milly any longer.’

‘There you are. The sight of the changing world is miraculous and heart-breaking, both at the same time.’

I reflected. ‘You’ll laugh at my optimism again, but for me it’s above all miraculous.’

‘But so it is for me too. The heart-breaking side of growing old is not in the things around one but in oneself.’

‘I don’t think so. You do lose in yourself as well, but you also gain.’

‘You lose much more than you gain. To tell you the truth, I don’t see what gain there is, anyhow. Can you tell me?’

‘It’s pleasant to have a long past behind one.’

‘You think you have it? I don’t, as far as mine is concerned. Just you try telling it over to yourself.’

‘I know it’s there. It gives depth to the present.’

‘All right. What else?’

‘You have a much greater intellectual command of things. You forget a great deal, certainly; but in a way even the things one has forgotten are available to one.’

‘In your line, maybe. For my part, I am more and more ignorant of everything that is not my own special subject. I should have to go back to the university like an ordinary undergraduate to be up to date with quantum physics.’

‘There’s nothing to stop you.’

‘Perhaps I will.’

‘It’s strange,’ I said. ‘We agree about everything; yet not in this. I can’t see what you lose in growing old.’

He smiled. ‘Youth.’

‘It’s not in itself a valuable thing.’

‘Youth and what the Italians so prettily call stamina. The vigour, the fire, that enables you to love and create. When you’ve lost that, you’ve lost everything.’

He had spoken in such a tone that I dared not accuse him of self-indulgence. There was something gnawing at him, something I knew nothing about—that I did not want to know about—that frightened me. It was perhaps that which was keeping us apart.

‘I shall never believe that you can no longer create,’ I said.

‘Bachelard says, “Great scientists are valuable to science in the first half of their lives and harmful in the second.” They consider me a scientist. All I can do now is try not to be too harmful.’

I made no reply. True or false, he believed what he was saying: it would have been useless to protest. It was understandable that my optimism should often irritate him: in a way it was an evasion of his problem. But what could I do? I could not tackle it for him. The best thing was to be quiet. We drove in silence as far as Champeaux.

‘This nave is really beautiful,’ said André as we went into the church. ‘It reminds me very much of the one at Sens, only its proportions are even finer.’

‘Yes, it is lovely. I have forgotten Sens.’

It’s the same thick single pillars alternating with slender twinned columns.’

‘What a memory you have!’

Conscientiously we looked at the nave, the: choir, the transept. The church was no less beautiful because I had climbed the Acropolis, but my state of mind was no longer the same as it had been in the days when we systematically combed the Ile de France in an aged second-hand car. Neither of us was really taking it in. I was not really interested in the carved capitals, nor in the misericords that had once amused us so.

As we left the church, André said to me, ‘Do you think the Truite d’Or is still there?’

‘Let’s go and see.’

The little inn at the water’s edge, with its simple, delightful food, had once been one of our favourite places. We celebrated our silver wedding there, but we had not been back since. This village, with its silence and its little cobbles, had not changed. We went right along the high street in both directions: the Truite d’Or had vanished. We did not like the restaurant in the forest where we stopped: perhaps because we compared it with our memories.

‘And what shall we do now?’ I asked.

‘We had thought of the Château de Vaux and the towers at Blandy.’

‘But do you want to go?’

‘Why not?’

He did not give a damn about them, and nor indeed did I; but neither of us liked to say so. What exactly was he thinking of, as we drove along the little leaf-scented country roads? About the desert of his future? I could not follow him on to that ground. I felt that there beside me he was alone. I was, too. Philippe had tried to telephone me several times. I had hung up as soon as I recognized his voice. I questioned myself. Had I been too demanding with regard to him? Had André been too scornfully indulgent? Was it this lack of harmony that had damaged him? I should have liked to talk about it with André, but I was afraid of starting a quarrel again.