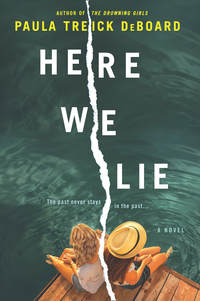

Here We Lie

Megan Mazeros and Lauren Mabrey are complete opposites on paper. Megan is a girl from a modest Midwest background, and Lauren is the daughter of a senator from an esteemed New England family. When they become roommates at a private women’s college, they forge a strong, albeit unlikely, friendship, sharing clothes, advice and their most intimate secrets.

The summer before senior year, Megan joins Lauren and her family on their private island off the coast of Maine. It should be a summer of relaxation, a last hurrah before graduation and the pressures of postcollege life. Then late one night, something unspeakable happens, searing through the framework of their friendship and tearing them apart. Many years later, Megan publicly comes forward about what happened that fateful night, revealing a horrible truth and threatening to expose long-buried secrets.

In this captivating and moving novel, Paula Treick DeBoard explores the power of friendship and secrets, and shows how hiding from the truth can lead to devastating consequences.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PAULA TREICK DEBOARD is the author of The Mourning Hours, The Fragile World and The Drowning Girls. She is a lecturer in writing at the University of California, Merced, and lives in Northern California with her husband, Will, and their four-legged brood.

Also By Paula Treick DeBoard

The Drowning Girls

The Fragile World

The Mourning Hours

Here We Lie

Paula Treick DeBoard

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Paula Treick DeBoard 2018

Paula Treick DeBoard asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2018 ISBN: 9781474083607

Praise for the novels of Paula Treick DeBoard

“In Paula Treick DeBoard’s latest breathtaking thriller, she paints a stark and chillingly real portrayal of a family torn apart by teenage transgressions. Gritty and inauspicious from the start, The Drowning Girls left me awestruck, revealing DeBoard’s true brilliance as an author. Spellbinding.”

—Mary Kubica, New York Times bestselling author of The Good Girl

“Think Fatal Attraction meets Desperate Housewives, and you have DeBoard’s latest thriller.... This is a gripping, tense suspense story with a good surprise ending.”

—Booklist

“Give this tale of domestic suspense, with its pitch-perfect pacing, to Gillian Flynn and Mary Kubica devotees.”

—Library Journal, starred review

“The Drowning Girls by Paula Treick DeBoard is cleverly plotted, full of twists and turns and so well-written that it pulls you in from page one. Genuinely suspenseful, DeBoard delivers a disturbing, multilayered, provocative novel that is impossible to put down.”

—Heather Gudenkauf, New York Times bestselling author of The Weight of Silence

“A heart-pounding look at what lies behind the deceptively placid veneer of the well-to-do suburbs. The kaleidoscopic view of innocence, danger, and malice shifts and twists as it races to a shattering conclusion.”

—Sophie Littlefield, bestselling author of The Guilty One

“This tale of a family in peril closes with a death that’s tragic and unexpected.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Fans of The Good Girl and The Luckiest Girl Alive, and really anyone who enjoys great suspense, have found their next must-read... I could not put it down.”

—Catherine McKenzie, bestselling author of Fractured and Hidden

“A coming-of-age tale about a family in crisis expertly told by Ms. DeBoard. The Fragile World examines how profound loss changes all who are forced to come to terms with it. Touching and compelling, it will move you.”

—Lesley Kagen, New York Times bestselling author of Whistling in the Dark and The Resurrection of Tess Blessing

“The Drowning Girls casts a spell as brilliant and alluring as the gated community of its setting. Paula Treick DeBoard maps this world of privilege and secrets with a deft hand... A suspenseful and compelling page-turner.”

—Karen Brown, author of The Clairvoyants and The Longings of Wayward Girls

For my sisters—the ones I was born with, and the ones I met along the way.

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

About the Author

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

OCTOBER 17, 2016

1998–1999

OCTOBER 10, 2016

FRESHMAN YEAR 1999–2000

OCTOBER 10, 2016

SUMMER 2000

OCTOBER 10, 2016

SOPHMORE YEAR 2000–2001

OCTOBER 10, 2016

SUMMER 2001

OCTOBER 12, 2016

JUNIOR YEAR 2001–2002

OCTOBER 12, 2016

SUMMER 2002

OCTOBER 15–17, 2016

2002 AND AFTER

OCTOBER 17, 2016

EPILOGUE FEBRUARY 2017

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Reader's Guide

Questions for Discussion

A Conversation with Paula Treick DeBoard

OCTOBER 17, 2016

Lauren

It was raining, and I was going to be late.

The press conference was scheduled for ten o’clock, and by the time I found a parking space in the cavernous garage, I had twenty minutes. I slipped once on the stairs, catching myself with a shocked hand on the sticky rail. Seventeen minutes.

I followed a cameraman toting a giant boom over his shoulder, navigating a path through the crowds of the capitol. Thank goodness I was wearing tennis shoes. I passed a group of schoolchildren on the steps, prim in their navy blazers and white button-down shirts. Their teacher’s question echoed off the concrete. “Who can tell me what it means that we have a separation and balance of powers?”

Only one hand shot into the air.

Balance of power, I thought. A good lesson for today.

I glanced at the display on my cell phone and quickened my pace, taking the rest of the steps two at a time. Twelve minutes.

* * *

I set my shoulder bag on the conveyer belt at the security checkpoint and watched as a bored guard picked through it with a gloved hand—wallet, cell phone, tube of hand lotion I’d forgotten about, an envelope with twenty-five dollars for the giving tree that should have been turned in to Emma’s teacher that morning. Shit. Annoyed, the guard removed a water bottle, waving the offending item in front of my face before tossing it into the trash container at his feet. His eyes flicked over me, already disinterested, already moving on to the next threat, which was apparently not a suburban mom in her stretchy pants.

I followed a directional sign for the press conference and hurried down hallways and around corners before arriving outside the door, where another line had formed. A woman at the front, officious in a burgundy blazer, was checking press credentials. My heart pounded. Each time one of the double doors swung open, I caught a glimpse of the people collected there, accompanied by their cameras and cords and laptops and phones.

Then I was at the front of the line, and the woman in the blazer was blocking my entry, shoulder pads increasing her bulk. “Show your credentials, please.”

I reached in my purse for my wallet. “I don’t have—”

“I can’t let anyone in without appropriate credentials,” the woman said, more loudly than necessary. She was a head shorter than me, but her voice carried enough authority to make up for it.

“I’m not a member of the press, but I have to get in there,” I pleaded. I flipped my wallet open to a picture of my face—my name, address, vital statistics. Behind my Rhode Island license was my old one, a Connecticut ID with my younger face, my maiden name.

She frowned at me, waving two others past, identification badges hanging from their necks. “Ma’am, I have to ask you to step to the side. This conference isn’t open to the general public.”

I gestured again with my open wallet, pointing desperately to my name. “I’m family,” I said finally, catching the attention of those waiting behind me. I could feel their ears perk up, the unsubtle uptick of their interest. Did she say she was family?

Finally, this got me her attention, in the form of slow blink and unabashed pity. “Go,” she hissed, and I darted past before she could change her mind.

* * *

I stayed close to the back wall, trying to find a vantage point but at the same time be invisible. At the front of the room was a podium with a microphone, and off to the side was the Connecticut state flag, its baroque shield visible on a blue background. A woman was at the microphone, saying Megan’s name.

And then she was on the stage, instantly recognizable despite the years between us. I gasped, catching the back of a folding chair for balance. She was more polished than I remembered, but then, she used to wear oversize sweatshirts and thrift store jeans, which either fit her waist or her inseam, but never both at once. She had been a teenager then, brash and funny and lovable and so different from me. The person at the microphone, of course, was thirty-five.

Still, I remembered her in our shoebox of a dorm room, drinking from my contraband bottle of schnapps.

I remembered her on our bike rides, the sun so bright on her hair that it looked like her head might, at any moment, burst into flame.

I remembered her that New Year’s Eve, wearing a borrowed dress, her feet wedged into my too-tight shoes.

And I remembered her as she’d looked that last night, sitting on the edge of my bed, hugging her arms to her chest.

Her voice now was shaky at first, as if from underuse. “I’m here today to right an old wrong,” she began. Camera shutters clicked, and she blinked away the flashes that momentarily blinded her. “I’m here today to tell you what happened to me fourteen years ago, and why, for far too long, I’ve kept silent.”

It was too much all of a sudden, and I bent down, hands on my knees, struggling for breath like a kid beaned in the stomach with a playground ball. Fourteen years. That was a long time to live a lie.

1998–1999

Megan

For years, my parents kept the painting I made in kindergarten on our refrigerator, secured by a free magnet from a local insurance company. The painting featured three stick figures so out of proportion they dwarfed the house and the tree in the background, and so tall they almost bumped against the giant yellow orb of the sun. Dad, Mom and me. That was my world, and we were happy. Not that Dad never raised his voice, not that Mom never nitpicked, not that I never misbehaved, not that we ever had any money. But still—happy. We had dinner together most nights, went to a movie once a month and ate out of the same giant tub of buttered popcorn, licking our fingers between handfuls. It was the sort of happiness that was so uncomplicated, I figured it would last forever.

Dad’s diagnosis came during my senior year in high school, and it stunned him, immediately, into submission. He seemed determined to live out his days in his recliner in front of TV Land and Nick at Nite, catching up on all the shows he’d missed during years of ten-hour workdays at one job site or another. That was when we still pronounced mesothelioma with hesitation, before we grew used to hearing it on television commercials, the symptoms filling the screen in a neat list of bullet points: chest pain, coughing, shortness of breath, weight loss. Dad had inhaled tiny asbestos fibers day after day and year after year, and those fibers had become trapped in his lungs like dust in a heating vent. The poor man’s cancer, he called it sometimes, because mesothelioma affected people who worked construction, who served as merchant marines.

Maybe because we didn’t know how to talk about what was happening, what would happen within twelve to eighteen months, according to the specialist in Kansas City, it was easier for Mom and me to join Dad in front of the television in our family room, listening to Sergeant Schultz claim he knew nothink! and laughing along as the POWs plotted their elaborate schemes, always a few steps ahead of the enemy. Our world had narrowed to this space with Dad’s coughs hanging in the air between us.

Before his diagnosis, Dad had trapped a garter snake in the backyard, and we kept it inside a terrarium filled with sand and rocks and a fake hollowed-out log from the pet store. We named the snake Zeke, and he was more Dad’s pet than mine, although once Dad became sick, it was my job to provide for Zeke’s general well-being and happiness.

Once a week, I bought a mouse at the pet store on my way home from school and transported it across town in my thirdhand Celica, the paper carton on the passenger seat jerking with sudden, frantic motions. At home, I dropped the mouse into the cage, and Dad and I watched until the poor thing was only a tumor-like hump in Zeke’s gullet. “Look at him go!” Dad would wheeze in his new, strange voice, with all the solemnity of someone announcing a round of golf.

All I could think was that it was too bad it had to be that way, that something had to die so something else could live. That was the lesson of biology textbooks and visits to the Kansas City Zoo, but it wasn’t so easy to watch it play out in our living room.

* * *

In high school, I had been one of the girls who was going somewhere. I’d ignored the boys in my class, sidestepping their advances at parties, letting the nerdy boys take me to prom. I was smart enough, one of the kids who always had the correct answer, even if I wasn’t the first to raise my hand. With my curly blondish hair and D-cup breasts, physical traits I’d inherited from my mom, I was pretty enough, too—and this was a near-lethal combination in Woodstock.

No matter what, I’d always promised myself, I wasn’t going to get trapped here.

Up until Dad’s diagnosis, I’d been planning to start Kansas State in the fall. But that spring and into the summer, I threw away the envelopes unopened—housing information, scholarship notifications. “Maybe next year,” Mom would say, her fingernails raking over the knots in my spine. We didn’t stop to talk about what that meant or what it would look like when the three-pronged family on the refrigerator was reduced to only two. After graduation, I got a job at the Woodstock Diner, a twenty-four-hour joint off I-70 that catered to truckers and the occasional harried families that spilled out of minivans, everyone passing through on their way to somewhere else. Always, they thought they were funny and clever, that they were better than this town and better than me. But in my black stretchy pants and white button-down, I was different from the Megan Mazeros I’d been before—honor student, soccer halfback, Daddy’s girl. Here I was witty and hardened as one of the veterans, old before my time.

“Where’s the concert?” one guy or another would invariably ask, making a peace sign or playing a few bars on an air guitar. “Different Woodstock,” I said over my shoulder, leading the way to a booth in the corner and presenting him with a sticky, laminated menu. “Although for a quarter, you can start up the jukebox.”

Inevitably, the guy grinned. Usually, the grin was accompanied by a tip.

Sometimes Dad was still awake when I came home from work, propped in his recliner. In the near dark of the family room, he wanted to talk in a way he wouldn’t during the daytime. “Just sit,” he urged. “Stay up with me a bit.”

I yawned, my legs tired and my feet aching, but I usually complied.

He always asked about work, and I would tell him about bumping into our old neighbor or receiving a twenty-dollar tip on an eight-dollar order. I didn’t mention that the neighbor hadn’t made eye contact, or that the twenty dollars had come with a phone number and the name of a local motel scrawled on the back. I didn’t tell him that I hated every second of it, the tedium of wiping down the same tables, of watching the minute hand slowly creep around the clock hour after hour. I didn’t tell him, as summer turned to fall, how I spent my time wondering what my friends were doing at KSU, how they liked the dorms, how they were doing in their classes.

“Look,” he said one night, pointing at the terrarium. Zeke was shedding his old skin, as he did every month or so, emerging new and shiny from a long, cylindrical husk that was so fragile, in a day it would crumble away to nothing. Dad made a funny choking sound, and when I turned, his face was shiny with tears.

“What’s wrong?”

“I can’t do this,” he wheezed.

Zeke must have been something for him to root for, the only thing that was thriving while the rest of us were in a horrible holding pattern, like a slow walk on a treadmill through purgatory. Dad couldn’t shed his lungs. He couldn’t grow a new pair, pink and shiny and tumor-free. Even if he’d been healthy enough for a transplant, I didn’t have an extra pair to give. Every morning as I spooned his breakfast into him, he said, “Well, maybe today’s the day, kiddo,” as if he were looking forward to it, as if death might arrive on our doorstep carrying balloons and an oversize check, payable immediately.

“Don’t be so morbid,” I told him, and even though it hurt him to talk, and there was nothing in the world to smile about, he managed his old Dad grin and said, “What morbid? I’m being practical.”

I swatted in his direction, and he said in his strange wheezy voice, “You could do all of us a favor. Put a pillow over my face. Done and done.”

“Is that supposed to be funny?”

He looked at me for a long time before he shook his head.

Mom and I took care of Dad in shifts, delivering reports to each other like nurses—noting intake and output, commenting on Dad’s general well-being and happiness. Mom had been young before all of this, but now her face sagged, puffy sacs hanging beneath her eyes. We didn’t even try to tell each other that it would all be okay, that it would work out. Our days were punctuated by the arrival of home health aides in cotton scrubs with cheerful, juvenile patterns—hearts and smiley faces, polka dots and rainbows. Their optimism was insulting. Who did they think they were kidding? Acting cheerful wasn’t going to change anything.

* * *

One night at the diner that September, I seated Kurt Haschke in a booth by himself, settling him with a menu and a glass of water. We’d gone to school together from kindergarten through our senior year and barely exchanged so much as an excuse me when we bumped into each other in the halls. He’d seemed as inoffensive and inconsequential as wallpaper. I asked, “Can I interest you in our dinner specials?” and he smiled at me, his face open and plain.

I thought, This is what you get, then.

Kurt came every night that week, waiting in the parking lot for the end of my shift. We kissed there, long and deep, my back to his truck, pinned between his erection and a half-ton of steel. That weekend and every other weekend when Dad was dying, I met Kurt at the ridge overlooking the Sands River and we had sex, sometimes in the bed of his lifted Dodge pickup, sometimes in the back seat of my falling-apart Celica, with a piece of the ceiling fabric dangling over our heads, sometimes on a blanket on the ground, never fully undressed.

Kurt wanted me to be his girlfriend, and I guess in a way, I was. There certainly wasn’t anyone else for me—between waiting tables and changing Dad’s soiled sheets, I couldn’t even consider the possibility. Kurt talked about us going places—not exotic ones, but just far enough away to be interesting—amusement parks and county fairs and festivals dedicated to things I wasn’t particularly interested in, cars and trains and beer.

“Mmm,” I said, neither a yes or no.

“I want you to meet my parents,” Kurt would say each time, practically while he was still zipping up. I had a vague memory of Mr. and Mrs. Haschke from various science fairs and class field trips, and while I always said, sure, eventually, I couldn’t imagine myself in their house, at their dinner table, as a part of their lives. It went without saying that Kurt wasn’t going to meet my parents, not now, when Mom’s face was etched with grief, when Dad was less and less lucid, his breath coming in ragged gasps.

* * *

Dad made it to Christmas, and we celebrated by putting on brave faces, as if this were any holiday and not our last one together. Mom picked out a spindly tree by herself, and we decorated it with Dad watching from his recliner, Mannheim Steamroller Christmas drowning out the sounds of his raspy breathing. He made it to New Year’s Eve, which we spent together, Mom drinking too much brandy and passing out on the couch, leaving me to get Dad into his bed.

Dad made it to February, which came with a snowstorm that clogged the roads and kept us homebound for days. He watched through the window as Mom and I took turns shoveling out the driveway, our limbs numb from the cold.

“I can’t take this anymore,” Dad told me that night, when I’d rolled him on his side to change his sheets, as efficient as a candy striper. “Look what it’s doing to you and your mom.”

“Don’t worry about us,” I said. “We want you as long as we can have you.”

“Not like this,” he said, tears leaking onto his pillow. “You don’t want me like this.”

Dad made it to March, and by that time, his speech was so distorted by pain, so breathy and thin, that it was hard to understand him at all. He was under hospice care, his pain managed by kindly nurses who talked about timing and dosages and offered gentle reassurances that left us numb. The doctor had told us that in the advanced stages of mesothelioma, Dad’s body would be racked with tumors, the cancer spreading to his lymph nodes, the lining of his heart, even his brain. Still, sometimes he rallied for brief moments, as if he were reminding us that he was still alive.

One afternoon, he tried to get my attention when Zeke once again shed his skin, a shiny new body separating from the old. I followed his limp gesture, but this time, I couldn’t summon enthusiasm for the process. I couldn’t make myself believe in new life and regeneration and second chances. We’d moved the terrarium closer, so Dad could see it from his hospital bed. Still, the effort of raising and lowering his arm had exhausted him, and his breaths were patchy.