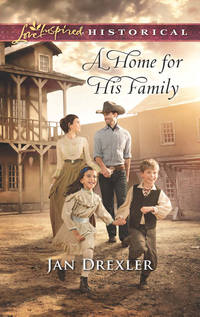

A Home for His Family

“Young man, put that gun down right now.” Margaret’s voice was as commanding as if she was reprimanding one of the Sunday school boys.

“Uncle Nate said to keep a gun on any strangers coming around, and that’s what I mean to do.” Charley squinted down the barrel and raised it a bit higher to aim at Margaret’s head.

This was getting nowhere, and Sarah was wet and cold.

“Come, now, surely you can see we’re no threat.” She smiled, but Charley only swung the gun barrel around to her. The gun wavered as he stared at her. “I know you, but I don’t know them.” He turned the shotgun back toward Uncle James.

“Charley, what are you doing?” The girl with the water pail came up the path behind him, and the boy tightened his grip on the gun.

“Keeping a gun on them, just like Uncle Nate said.”

The girl, half a head taller than the boy and a little older, eyed Sarah as she pulled a dirty blanket tighter around her small body.

“Are you two out here alone?” Sarah smiled at them. “Where is your uncle?”

The children exchanged glances.

“No, ma’am, we aren’t alone,” the girl said. “Uncle Nate went hunting, but he’ll be back soon.” She pulled at her brother’s sleeve. “Come on, Charley. We have to get back.”

Charley let the gun barrel droop and backed away.

“There aren’t any cabins around here.” James sounded doubtful, as if these children would lie.

“We have a wagon. We’ve been traveling the longest time.”

Charley turned on the girl. “Olivia, you know Uncle Nate said not to talk to strangers.” His voice was a furious whisper.

“They aren’t strangers. They’re nice people.” The girl’s whispered answer made Sarah smile again.

“Why don’t you bring your family to our cabin for a warm meal? You can wait there until this storm blows over.”

The two looked at each other.

“Uncle Nate said to stay with the wagon.” Sarah could hear doubt in the boy’s voice.

His sister pulled on his sleeve again. “Lucy is already cold, and night’s coming. It’s just going to get colder.”

“We have stew on the fire,” Sarah said. The thought of the waiting meal made her stomach growl.

“Why are you even asking them?” Margaret stepped forward and took each of the children’s hands in her own. “Now take us to your wagon, and let us take care of the rest.”

The children looked at each other and shrugged, giving in to Margaret’s authority. They led the way to the covered wagon, listing on a broken axle, at the side of the trail. The canvas cover whipped in the wind. So Mr. Colby had made it almost all the way to town before breaking down. Another half mile and he would have reached safety. But where they were now... Sarah glanced at the bare slopes around them, peppered with tree stumps.

As they drew close, Olivia dropped Margaret’s hand and ran to the wagon.

“Lucy! Lucy, where are you?”

A curly head popped over the side of the crippled wagon, and a young girl with round eyes stuck her thumb in her mouth and stared. Sarah guessed she looked about five years old.

Out here, away from the shelter of the trees and brush along the creek, the wind roared. Sarah marveled at its fury, and the children huddled against the gust.

Margaret stepped to the end of the wagon and looked in. “Is this all of you? Where is the rest of your family?”

Olivia’s teeth chattered. “There’s only Uncle Nate. We’re supposed to wait here until he gets back.”

Sarah stamped her feet to warm them. Mr. Colby should know how dangerous it was to wander around this area alone. Uncle James had warned her and Margaret to never go anywhere outside the mining camp without him after they had arrived last evening. Between claim jumpers and Sioux warriors scouring the hills, even visiting a sick neighbor was a risk.

She stepped forward and put her own warm cloak around Olivia’s shoulders. “He can find you at our cabin. We need to get in out of the weather, and you need a hot meal.”

Charley looked at her, his lips blue in the rapidly falling temperatures. “How will Uncle Nate find us?”

“I’ll leave him a note.”

Olivia and Charley exchanged glances, and then Olivia nodded. “All right, I think he’ll be able to find us there, if it isn’t too far.”

Sarah scratched a brief message on a broken board she found near the trail and put it in a prominent place next to the campfire. She raked ashes over the low coals with a stick and stirred. The fire would die on its own.

She took Olivia’s hand in hers as Margaret lifted Lucy out of the wagon. Uncle James untied the horses, Charley took his mule and they started up the trail toward home.

Sarah’s breath puffed as they climbed the steep hill, her mind flitting between worry and irritation with the children’s uncle Nate. These children needed her, no matter what their uncle said. Somehow she would see that they received the care and education they deserved.

* * *

As the snowfall grew heavier, obscuring the distant mountains, Nate gave up. He’d been wandering these bare, brown hills since midmorning and hadn’t seen any sign of game. He and the children would just have to make do with the few biscuits left from last night’s supper.

When the wagon axle had finally broken yesterday afternoon, he thought the freight master would have helped them make repairs, but the man had only moved the crippled wagon off the trail and then set on his way with the bull train again.

“We’re less than a mile from town—you’ll be fine until we send help back for you. Just keep an eye out for those Indians.”

And then they were gone, leaving Nate and the children alone.

Less than a mile from Deadwood? It might as well be twenty, or fifty, when everything they owned was lying by the side of the road. By the time the gray light of the cloudy afternoon started fading, Nate knew the bull train driver had forgotten them.

They had spent the night on their own with little food and a fitful fire. Morning had brought clouds building in the northwest and he’d hoped he’d be able to find a turkey or squirrel before too long. But here he was coming home empty-handed.

As he hurried over the last rise, Nate’s empty stomach plummeted like a stone at the sight of the wagon. The wind had torn one corner of the canvas cover and it flapped wildly. Why hadn’t Charley tied that down? Didn’t he know his sisters and all their supplies were exposed to this weather?

And why hadn’t they kept the fire going? They had to be freezing.

The hair on the back of Nate’s neck prickled. The wagon tilted with the blasting gusts of wind. It was too quiet. The horses were missing. Even Loretta was nowhere in sight.

Nate broke into a run.

When he reached the wagon, he closed his eyes, dreading what he might see inside. They were just children. He had been so stupid to leave them. He had let his brother down again.

He gripped the worn wooden end gate and slowly opened his eyes. Nothing. Just the barrels and boxes of supplies. The children were gone.

Why had he taken so long? He should have stayed closer to the wagon. He had been warned about the Indians in the area, attacking any settlers who were foolish enough to venture out without being heavily armed.

He knew why he had taken the risk. No game. No food. He had had to leave them for a few hours.

He turned into the wind and scanned the hills rising above.

“Charley!” A gust snatched his voice away. “Olivia! Lucy!”

A wolf’s howl floating on the wild wind was his only answer as he slumped against the wagon box, his eyes blurred with the cold. It had been the same when he and Andrew had returned from the war, back home to the abandoned farm. The wind had howled that afternoon, too, with a fierce thunderstorm. But they were gone. Ma, Pa, Mattie... Ma and Pa were dead, but Mattie was lost. None of the neighbors knew where she had gone, or even when. Years of searching had brought him only wisps of clues, rumors that this cowboy or that miner had seen her in Tombstone, or Denver or Abilene, but she was gone without a trace.

Nate’s legs gave way as he sank to the ground.

The wolf’s howl came again, answered by several others. A pack on the hunt? Or a Sioux raiding party?

Nate scrambled to the fire, pulling his rifle with him. He blew the coals to life again and fed the flames with a few small sticks left near the wagon and a stray board that he threw on when the blaze was strong enough. A fire should keep the wolves away, at least until dark. Until then, he could search for some sign of which way the children had gone.

He took a deep breath, shutting down the panic that threatened to consume him. The panic that would make him freeze in a shuddering mess if he gave in to it. Closing his eyes, he whooshed out the breath and filled his lungs again. Where could they be? Think.

The wind gusted again with a force strong enough to send the canvas wagon cover flapping. With the rising wind, perhaps the children had gone to seek a better shelter than the crippled wagon. He clung to that hope. The alternative—that they had been stolen along with the horses—was too horrible to consider.

Chapter Two

The walk back to the cabin wasn’t more than a half mile, but Sarah’s feet were frozen by the time they climbed the final slope up from the trail at the edge of town. The wind pierced her wool dress.

Charley and Uncle James took the horses and mule into the lean-to where they would get some shelter, as Aunt Margaret led the way into the house. Warmth enveloped Sarah as she stopped just inside the door. She took the cloak from Olivia and guided the girls closer to the fireplace.

Lucy watched the glowing coals while Olivia folded the blanket her sister had been using as a wrap and laid it on the wood plank floor.

“You girls must be frozen.” Aunt Margaret added a few sticks to the fire and swung the kettle over the flames. “Sit right here while we warm up the stew. Supper will be ready soon enough.”

She left the girls to get settled on the blanket while she pulled Sarah to the side of the cabin where Uncle James had built a cupboard and small table.

“What can we feed them? I do wish we had been able to bring Cook out West with us, and Susan. They’d know what to do.”

She wrung her hands, but Sarah stopped her with a touch. “You said you wouldn’t complain about leaving the servants behind in Boston.”

“That was before I found out we would be cooking over an open fireplace. How can we have guests in conditions like this?”

Sarah put one arm around the shorter woman’s shoulders. “We’ll put another can of vegetables in the pot and some water to stretch it out. Meanwhile, we’ll make a batch of biscuits. That will fill everyone’s stomachs.”

“I’m so glad you know your way around a kitchen.” Margaret glanced at the girls, content to sit near the fire. “I’ll learn as quickly as I can, but I don’t think I could make a biscuit if my life depended on it!”

“Then we’ll do it together.” Sarah put a bowl on the table, along with a can of flour and Uncle James’s jar of sourdough starter. She squelched the irritation that always rose whenever Aunt Margaret’s helplessness showed its face. One thing Dr. Amelia Bennett had expounded upon frequently at her Sunday afternoon meetings was the careless way women of the privileged classes in Boston wasted the hours of their days, while their less fortunate sisters in the mills and saloons longed for the advantages denied them because of lack of education. But with all the education available to her, Aunt Margaret had never even learned to do a simple task like baking.

Sarah took a deep breath. Dr. Bennett wasn’t here, but she was. She would help her aunt in any way she could, even if it was only to teach her how to make sourdough biscuits.

While they mixed the dough, James and Charley came in the door, bringing a fresh blast of cold air and stomping feet.

“It’s getting even colder out there as the sun goes down.” James sat in his chair near the fireplace and pulled off his boots.

“But Loretta and the horses will be safe in the lean-to, won’t they?” Charley hung his coat on a hook and joined his sisters by the fireplace.

“Sure they will. Animals can survive pretty well as long as they have food and shelter.”

“What about Uncle Nate?” Olivia turned to Uncle James, and then looked at Sarah. “Will he be all right?”

Sarah smiled at her. “We’ll pray he will be.”

A dull ache spread across her forehead as she rolled out the dough and cut biscuits. Nate’s crooked smile swam in her memory. Was he warm enough? Would he be able to find the cabin? She didn’t have any choice but to trust God for his safety.

“What made your uncle decide to bring you to Deadwood?” Uncle James asked.

The two children exchanged glances.

“There were some ladies in our church who wanted us to go to the orphans’ home,” Olivia said. “Uncle Nate said he wouldn’t do that. He said he could take care of us.”

“They called the sheriff to arrest Uncle Nate.” Charley scooted closer to the fire.

“Charley, don’t exaggerate. They only said they might. They said will’s fare was at stake.” Olivia looked at Sarah. “What does that mean?”

Sarah laid the biscuits in the bottom of the Dutch oven. “I think they meant welfare. That your welfare was at stake. It sounds like they wanted what was best for you.”

“Yes, that’s it. That’s what they said. But Uncle Nate said they didn’t know the situation and he’d see what was what if they tried to take us away from him.”

Aunt Margaret cleared her throat and Sarah saw her exchange glances with Uncle James.

“What was your situation?” Uncle James leaned back in his chair, ready to hear the children’s version of the event.

“There was a fire...” Olivia bit her lip.

“Our house burned.” Charley picked up the story as Olivia fell silent. “Pa and Uncle Nate got the three of us out of the house and then went back in to get Mama.”

The children stared at the fireplace. Sarah set the Dutch oven in the coals and then sat next to Olivia with her arm around the girl’s shoulders.

“You don’t have to tell us the rest, if you don’t want to.”

Charley went on. “When Uncle Nate came out of the house, his clothes were on fire.” His voice was hollow, remembering.

Olivia hid her face in Sarah’s dress. “I could hear Mama,” she whispered. “She and Papa were still in the house.”

“But Uncle Nate,” Charley said, his voice strengthening, “he didn’t want to give up. He kept trying to go back inside, to save them, but the neighbors were there, and they wouldn’t let him. And then the roof fell down and everything was gone.”

“Uncle Nate was hurt awful bad.” Olivia sat up and took Charley’s hand. “He almost died, too.”

“That’s when the ladies at church said we should go to the home.” Charley wiped at his eyes. “But Uncle Nate just kept saying no.”

“It sounds like your uncle loves you very much.” James laid his hand on Charley’s shoulder.

Charley leaned against Uncle James’s knee. The children fell silent, looking into the fire.

Sarah watched Lucy. She didn’t look at her sister or brother, and she hadn’t seemed to hear what they had been talking about. She sat on the folded blanket, staring at the flames, lost in a world of her own. During their walk from the crippled wagon to the cabin, the little girl hadn’t made a sound, but had passively held Sarah’s hand as they walked.

At the time, Sarah had thought Lucy was cold and only wanted to get to the cabin. But now with the others talking and in the warm room, she was still closed into her own thoughts. Could it be that she was deaf? Or was something else wrong?

The biscuits baked quickly in the Dutch oven, and supper was soon ready. Everyone ate in front of the fire, and Sarah was glad to see how quickly the biscuits disappeared, except the ones Olivia had insisted they save for their uncle along with a portion of the stew.

After they were done eating, Lucy climbed into Sarah’s lap. The little one melted into her arms without a word, the ever-present thumb stuck in her mouth.

“You stay where you are,” Margaret said as Sarah started to put Lucy back on the floor so she could help clean up from the meal. “Her eyes are closing already.”

Sarah settled back in her chair, enjoying the soft sweetness of holding a child in her arms. These children had suffered so much, and their story brought memories of her own losses to the surface. How well she remembered the awful loneliness the day her parents had died, even though she had been much younger than Olivia and Charley. She had been about Lucy’s age when she had gone to the orphanage.

She laid her cheek on Lucy’s head, the girl’s curly hair tickling Sarah’s skin, pulling an old longing out from the corner where she had buried it long ago. The room blurred as she held Lucy tighter.

All those years in the orphanage, until Uncle James returned from the mission field when she was seventeen years old, she had never had the thought that she would marry and have children. She had changed enough diapers, cleaned enough dirty ears and soothed enough sore hearts to have been mother to a dozen families.

Marriage and children meant opening her heart to love, and she refused to consider that possibility. Loving someone meant only pain and heartache when they died. She wouldn’t willingly put herself through that misery again.

She still enjoyed children, but only when they belonged to someone else. Teaching filled that desire quite nicely.

Sarah hummed under her breath as Lucy relaxed into sleep. Charley and Olivia had settled on the floor in front of the fire, where they were setting up Uncle James’s checkers game.

Where was their uncle? She prayed again for his safety in the blowing storm.

* * *

Nate stood in the abandoned camp. His hastily built fire was already dying down, and the empty canvas flapped behind him. Snow swirled. Before too long any traces of where the children had gone would be covered.

The wind swung around to the north, bringing the smell of wood smoke. A fire. People. Friends? A mining camp?

Or an Indian encampment.

He needed to find the children. He had to take the risk.

Setting his face to the wind, he followed the smoke trail to a line of cottonwoods along Whitewood Creek. He had reached the outskirts of the mining camp, and the thin thread of smoke had turned into a heavy cloud hanging in the gulch. He paused on the creek bank. Ice lined the edges of the water. The children had either been taken away, or they had run off to hide. It wouldn’t take long for them to freeze to death on an evening like this one.

There. Hoofprints in the mud. Nate followed the trail up away from the creek until he came to a cabin sheltered among a few trees at the edge of the rimrock. A lean-to built against the steep hill behind the cabin was crowded with horses. Even in the fading light, he recognized Scout and Ginger. Pete’s and Dan’s bay rumps were next to them, and then the mule’s black flank.

Nate tried not to think of what kind of men he might find in this cabin. This was where the horses were, so horse thieves, most likely. But were they kidnappers? Murderers?

He pounded on the heavy wooden door and then stepped back, gripping his rifle.

The middle-aged man who cracked open the door wasn’t the rough outlaw he expected. The white shirt, wool vest and string tie would fit in back home in Michigan, but Nate hadn’t seen a man dressed this fancy since they left Chicago in March.

“Yes, can I help you?” The man poked his head out the door.

“I’m looking for some children.”

“Uncle Nate! That’s Uncle Nate out there!”

Charley’s voice. Relief washed over Nate, leaving his knees weak.

The man smiled and he opened the door. “Come in. We’ve been expecting you.”

Nate stepped into the warmth. Charley jumped up from a checkers game on the floor in front of the fireplace and ran toward him, wrapping his arms around Nate’s middle without regard to his soaking and icy clothes. Olivia joined her brother in a hug, but Lucy stayed where she was, asleep on the lap of...

Nate dropped his gaze to the floor. Lucy was in the lap of the young woman from the stagecoach. Willowy, soft, her dark hair gleaming in the lamplight, the young woman held the sleeping child close in a loving embrace. He couldn’t think of a more peaceful scene.

A round woman dressed in stylish brown bustled up to the little group. “Oh my, you must be frozen. You just come right in and change out of those wet clothes. We saved some supper for you.”

Nate ran his fingers over the cheeks of both the older children. Yes, they were here, safe, sound and warm. It was hard to see their faces, his eyes had filled so suddenly.

“I thank you, ma’am, for caring for the children like this. I can’t tell you how I felt when I got back to the wagon and they were gone.”

“Didn’t you get our note?”

Nate met the young woman’s deep blue eyes.

“Uh, no, miss. I didn’t see any note.”

“We found the children alone with the storm coming up, so we brought them here.” Pink tinged her cheeks as she spoke, her voice as soft as feathers. “I left word of where we were going on a broken plank. I leaned it against the rocks around the fire.”

“A piece of wood?” The piece of wood he had laid on the fire when the wolves were howling. He could have saved himself some worry if only he had taken the time. Then Nate looked back at Charley and Olivia, their arms still holding him tight around the waist. If he had lost them, after all they had been through, he would never have forgiven himself.

“No matter. You’re here now,” said the man. He put his arm around the shorter woman. “I suppose some introductions are in order. I’m James MacFarland, and this is my wife, Margaret.”

“Ma’am.” Nate snatched the worn hat off his head and nodded to her.

“And our niece, Sarah MacFarland.”

She had a name. He nodded in her direction.

“I’m Nate Colby.”

“Well, Mr. Colby, there are dry clothes waiting for you behind that curtain. While you’re changing, I’ll dish up some stew for you.” Mrs. MacFarland waved her hand toward the corner of the little cabin where a space had been curtained off.

Nate untangled himself from Charley’s and Olivia’s arms and ducked behind the curtains. On the small bed were a shirt and trousers, faded and worn, but clean. When he slipped the faded gray shirt over his head, he paused. There was no collar. Nothing to cover his neck.

The children had gotten used to the angry red scars left by the burns that had nearly killed him, but these people—Sarah...Miss MacFarland—what would they say?

“Uncle Nate, aren’t you hungry?” Charley was waiting for him.

Nate pulled the collarless shirt up as high as he could and gathered his wet things. He didn’t really have a choice.

* * *

Sarah stroked Lucy’s soft hair, surprised she still slept after all the noise Olivia and Charley had made when Nate came in. She had felt like shouting along with the children, she was so relieved to see him safe.

When he stepped out from behind the makeshift curtain, Sarah couldn’t keep her gaze from flitting to his collar line. When the children had told of how their uncle had been burned in the fire, she hadn’t realized how badly he had been injured. Scars covered the backs of his hands and the left side of his neck like splashes of blood shining bright red in the light. Suddenly aware she was staring, Sarah turned her attention back to the girl in her lap, but not before she saw Nate’s self-conscious tug at the shirt’s neckline, as if he were ashamed of the evidence of his heroism.

“Come sit here, Uncle Nate.” Charley directed his uncle to the chair closest to the fireplace and Olivia gave him a plate of stew and two biscuits she had saved for him. Nate didn’t hesitate, but dug his spoon into the rich, brown gravy and chunks of potato.