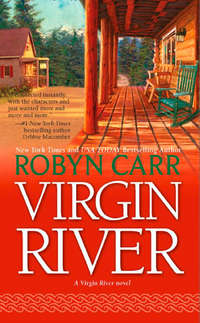

Virgin River

“There must be something…”

“Nearest thing is Jo Ellen’s place—she’s got a nice spare room over the garage she lets out sometimes. But you wouldn’t want to stay there. That husband of hers can be a handful. He’s been slapped down by more than one woman in Virgin River—and it’d be a bad thing, you in your nightie, Jo Ellen sound asleep and him getting ideas. He’s a groper, that one.”

Oh, God, Mel thought. Every second this place sounded worse and worse.

“Tell you what we’ll do, girl. I’ll light the hot water heater, turn on the refrigerator and heater, then we’ll go get a hot meal.”

“At the Pie and Coffee shop?”

“That place closed down three years back,” she said.

“But you sent me a picture of it—like it was where I’d be getting lunch or dinner for the next year!”

“Details. Lord, you do get yourself worked up.”

“Worked up!?”

“Go jump in the truck and I’ll be right along,” she commanded. Then ignoring Mel completely, she went to the refrigerator and stooped to plug it in. The light went on immediately and Mrs. McCrea reached inside to adjust the temperature and close the door. The refrigerator’s motor made an unhealthy grinding sound as it fired up.

Mel went to the Suburban as she’d been told, but it was so high off the ground she found herself grabbing the inside of the open door and nearly crawling inside. She felt a lot safer here than in the house where her hostess would be lighting a gas water heater. She had a passing thought that if it blew up and destroyed the cabin, they could cut their loses here and now.

Once in the passenger seat, she looked over her shoulder to see the back of the Suburban was full of pillows, blankets and boxes. Supplies for the falling-down house, she assumed. Well, if she couldn’t get out of here tonight, she could sleep in her car if she had to. She wouldn’t freeze to death with all those blankets. But then, at first light…

A few minutes passed and then Mrs. McCrea came out of the cottage and pulled the door closed. No locking up. Mel was impressed by the agility with which the old woman got herself into the Suburban. She put a foot on the step, grabbed the handle above the door with one hand, the armrest with the other and bounced herself right into the seat. She had a rather large pillow to sit on and her seat was pushed way up so she could reach the pedals. Without a word, she put the vehicle in gear and expertly backed down the narrow drive out onto the road.

“When we talked a couple weeks ago, you said you were pretty tough,” Mrs. McCrea reminded her.

“I am. I’ve been in charge of a women’s wing at a three-thousand-bed county hospital for the past two years. We got all the most challenging cases and hopeless patients, and did a damn fine job if I do say so myself. Before that, I spent years in the emergency room in downtown L.A., a very tough place by anyone’s standards. By tough, I thought you meant medically. I didn’t know you meant I should be an experienced frontier woman.”

“Lord, you do go on. You’ll feel better after some food.”

“I hope so,” Mel replied. But, inside she was saying, I can’t stay here. This was crazy, I’m admitting it and getting the hell out of here. The only thing she really dreaded was owning up to Joey.

They didn’t talk during the drive. In Mel’s mind there wasn’t much to say. Plus, she was fascinated by the ease, speed and finesse with which Ms. McCrea handled the big Suburban, bouncing down the tree-lined road and around the tight curves in the pouring rain.

She had thought this might be a respite from pain and loneliness and fear. A relief from the stress of patients who were either the perpetrators or victims of crimes, or devastatingly poor and without resources or hope. When she saw the pictures of the cute little town, it was easy to imagine a homey place where people needed her. She saw herself blooming under the grateful thanks of rosy-cheeked country patients. Meaningful work was the one thing that had always cut through any troubling personal issues. Not to mention the lift of escaping the smog and traffic and getting back to nature in the pristine beauty of the forest. She just never thought she’d be getting this far back to nature.

The prospect of delivering babies for mostly uninsured women in rural Virgin River had closed the deal. Working as a nurse practitioner was satisfying, but midwifery was her true calling.

Joey was her only family now; she wanted Mel to come to Colorado Springs and stay with her, her husband Bill and their three children. But Mel hadn’t wanted to trade one city for another, even though Colorado Springs was considerably smaller. Now, in the absence of any better ideas, she would be forced to look for work there.

As they passed through what seemed to be a town, she grimaced again. “Is this the town? Because this wasn’t in the pictures you sent me, either.”

“Virgin River,” she said. “Such as it is. Looks a lot better in daylight, that’s for sure. Damn, this is a big rain. March always brings us this nasty weather. That’s the doc’s house there, where he sees patients when they come to him. He makes a lot of house calls, too. The library,” she pointed. “Open Tuesdays.”

They passed a pleasant-looking steepled church, which appeared to be boarded up, but at least she recognized it. There was the store, much older and more worn, the proprietor just locking the front door for the night. A dozen houses lined the street—small and old. “Where’s the schoolhouse?” Mel asked.

“What schoolhouse?” Mrs. McCrea countered.

“The one in the picture you sent to the recruiter.”

“Hmm. Can’t imagine where I got that. We don’t have a school. Yet.”

“God,” Mel groaned.

The street was wide, but dark and vacant—there were no streetlights. The old woman must have gone through one of her ancient photo albums to come up with the pictures. Or maybe she snapped a few of another town.

Across the street from the doctor’s house Mrs. McCrea pulled up to the front of what looked like a large cabin with a wide porch and big yard, but the neon sign in the window that said Open clued her in to the fact that it was a tavern or café. “Come on,” Mrs. McCrea said. “Let’s warm up your belly and your mood.”

“Thank you,” Mel said, trying to be polite. She was starving and didn’t want an attitude to cost her her dinner, though she wasn’t optimistic that anything but her stomach would be warm. She looked at her watch. Seven o’clock.

Mrs. McCrea shook out her slicker on the porch before going in, but Mel wasn’t wearing a raincoat. Nor did she have an umbrella. Her jacket was now drenched and she smelled like wet sheep.

Once inside, she was rather pleasantly surprised. It was dark and woody with a fire ablaze in a big stone hearth. The polished wood floors were shiny clean and something smelled good, edible. Over a long bar, above rows of shelved liquor bottles, was a huge mounted fish; on another wall, a bearskin so big it covered half the wall. Over the door, a stag’s head. Whew. A hunting lodge? There were about a dozen tables sans tablecloths and only one customer at the bar; the old man who had pulled her out of the mud sat slumped over a drink.

Behind the bar stood a tall man in a plaid shirt with sleeves rolled up, polishing a glass with a towel. He looked to be in his late thirties and wore his brown hair cropped close. He lifted expressive brows and his chin in greeting as they entered. Then his lips curved in a smile.

“Sit here,” Hope McCrea said, indicating a table near the fire. “I’ll get you something.”

Mel took off her coat and hung it over the chair back near the fire to dry. She warmed herself, vigorously rubbing her icy hands together in front of the flames. This was more what she had expected—a cozy, clean cabin, a blazing fire, a meal ready on the stove. She could do without the dead animals, but this is what you get in hunting country.

“Here,” the old woman said, pressing a small glass of amber liquid into her hand. “This’ll warm you up. Jack’s got some stew on the stove and bread in the warmer. We’ll fix you up.”

“What is it?” she asked.

“Brandy. You gonna be able to get that down?”

“Damn right,” she said, taking a grateful sip and feeling it burn its way down to her empty belly. She let her eyes drift closed for a moment, appreciating the unexpected fine quality. She looked back at the bar, but the bartender had disappeared. “That guy,” she finally said, indicating the only customer. “He pulled me out of the ditch.”

“Doc Mullins,” she explained. “You might as well meet him right now, if you’re okay to leave the fire.”

“Why bother?” Mel said. “I told you—I’m not staying.”

“Fine,” the old woman said tiredly. “Then you can say hello and goodbye all at once. Come on.” She turned and walked toward the old doctor and with a weary sigh, Mel followed. “Doc, this is Melinda Monroe, in case you didn’t catch the name before. Miss Monroe, meet Doc Mullins.”

He looked up from his drink with rheumy eyes and regarded her, but his arthritic hands never left his glass. He gave another single nod.

“Thanks again,” Mel said. “For pulling me out.”

The old doctor gave a nod, looking back to his drink.

So much for the friendly small-town atmosphere, she thought. Mrs. McCrea was walking back to the fireplace. She plunked herself down at the table.

“Excuse me,” Mel said to the doctor. He turned his gaze toward her, but his bushy white brows were drawn together in a definite scowl, peering over the top of his glasses. His white hair was so thin over his freckled scalp that it almost appeared he had more hair on his brows than his head. “Pleasure to meet you. So, you wanted help up here?” He just seemed to glare at her. “You didn’t want help? Which is it?”

“I don’t much need any help,” he told her gruffly. “But that old woman’s been trying to get a doc to replace me for years. She’s driven.”

“And why is that?” Mel bravely asked.

“Couldn’t imagine.” He looked back into his glass. “Maybe she just doesn’t like me. Since I don’t like her that much, makes no difference.”

The bartender, and presumably proprietor, was carrying a steaming bowl out of the back, but he paused at the end of the bar and watched as Mel conversed with the old doctor.

“Well, no worries, mate,” Mel responded, “I’m not staying. It was grossly misrepresented. I’ll be leaving in the morning, as soon as the rain lets up.”

“Wasted your time, did you?” he asked, not looking at her.

“Apparently. It’s bad enough the place isn’t what I was told it would be, but how about the complication that you have no use for a practitioner or midwife?”

“There you go,” he said.

Mel sighed. She hoped she could find a decent job in Colorado.

A young man, a teenager, brought a rack of glasses from the kitchen into the bar. He sported much the same look as the bartender with his short cropped, thick brown hair, flannel shirt and jeans. Handsome kid, she thought, taking in his strong jaw, straight nose, heavy brows. As he was about to put the rack under the bar, he stopped short, staring at Mel in surprise. His eyes grew wide; his mouth dropped open for a second. She tilted her head slightly and treated him to a smile. He closed his mouth slowly, but stood frozen, holding the glasses.

Mel turned away from the boy and the doctor. She headed for Mrs. McCrea’s table. The bartender set down a bowl along with a napkin and utensils, then stood there awaiting her. He held the chair for her. Close up, she saw how big a guy he was—over six feet and broad-shouldered. “Miserable weather for your first night in Virgin River,” he said pleasantly.

“Miss Melinda Monroe, this is Jack Sheridan. Jack, Miss Monroe.”

Mel felt the urge to correct them—tell them it was Mrs. But she didn’t because she didn’t want to explain that there was no longer a Mr. Monroe, a Dr. Monroe in fact. So she said, “Pleased to meet you. Thank you,” she added, accepting the stew.

“This is a beautiful place, when the weather cooperates,” he said.

“I’m sure it is,” she muttered, not looking at him.

“You should give it a day or two,” he suggested.

She dipped her spoon into the stew and gave it a taste. He hovered near the table for a moment. Then she looked up at him and said in some surprise, “This is delicious.”

“Squirrel,” he said.

She choked.

“Just kidding,” he said, grinning at her. “Beef. Corn fed.”

“Forgive me if my sense of humor is a bit off,” she replied irritably. “It’s been a long and rather arduous day.”

“Has it now?” he said. “Good thing I got the cork out of the Remy, then.” He went back behind the bar and she looked over her shoulder at him. He seemed to confer briefly and quietly with the young man, who continued to stare at her. His son, Mel decided.

“I don’t know that you have to be quite so pissy,” Mrs. McCrea said. “I didn’t sense any of this attitude when we talked on the phone.” She dug into her purse and pulled out a pack of cigarettes. She shook one out and lit it—this explained the gravelly voice.

“Do you have to smoke?” Mel asked her.

“Unfortunately, I do,” Mrs. McCrea said, taking a long drag.

Mel just shook her head in frustration. She held her tongue. It was settled, she was leaving in the morning and would have to sleep in the car, so why exacerbate things by continuing to complain? Hope McCrea had certainly gotten the message by now. Mel ate the delicious stew, sipped the brandy, and felt a bit more secure once her belly was full and her head a tad light. There, she thought. That is better. I can make it through the night in this dump. God knows, I’ve been through worse.

It had been nine months since her husband, Mark, had stopped off at a convenience store after working a long night shift in the emergency room. He had wanted milk for his cereal. But what he got was three bullets, point-blank to the chest, killing him instantly. There had been a robbery in progress, right in a store he and Mel dropped into at least three times a week. It had ended the life she loved.

Spending the night in her car, in the rain, would be nothing by comparison.

***

Jack delivered a second Remy Martin to Miss Monroe, but she had declined a second serving of stew. He stayed behind the bar while she ate, drank and seemed to glower at Hope as she smoked. It caused him to chuckle to himself. The girl had a little spirit. What she also had was looks. Petite, blond, flashing blue eyes, a small heart-shaped mouth, and a backside in a pair of jeans that was just awesome. When the women left, he said to Doc Mullins, “Thanks a lot. You could have cut the girl some slack. We haven’t had anything pretty to look at around here since Bradley’s old golden retriever died last fall.”

“Humph,” the doctor said.

Ricky came behind the bar and stood next to Jack. “Yeah,” he heartily agreed. “Holy God, Doc. What’s the matter with you? Can’t you think of the rest of us sometimes?”

“Down boy,” Jack laughed, draping an arm over his shoulders. “She’s outta your league.”

“Yeah? She’s outta yours, too,” Rick said, grinning.

“You can shove off anytime. There isn’t going to be anyone out tonight,” Jack told Rick. “Take a little of that stew home to your grandma.”

“Yeah, thanks,” he said. “See you tomorrow.”

When Rick had gone, Jack hovered over Doc and said, “If you had a little help, you could do more fishing.”

“Don’t need help, thanks,” he said.

“Oh, there’s that again,” Jack said with a smile. Any suggestion Hope had made of getting Doc some help was stubbornly rebuffed. Doc might be the most obstinate and pigheaded man in town. He was also old, arthritic and seemed to be slowing down more each year.

“Hit me again,” the doctor said.

“I thought we had a deal,” Jack said.

“Half, then. This goddamn rain is killing me. My bones are cold.” He looked up at Jack. “I did pull that little strumpet out of the ditch in the freezing rain.”

“She’s probably not a strumpet,” Jack said. “I could never be that lucky.” Jack tipped the bottle of bourbon over the old man’s glass and gave him a shot. But then he put the bottle on the shelf. It was his habit to look out for Doc and left unchecked, he might have a bit too much. He didn’t feel like going out in the rain to be sure Doc got across the street all right. Doc didn’t keep a supply at home, doing his drinking only at Jack’s, which kept it under control.

Couldn’t blame the old boy—he was overworked and lonely. Not to mention prickly.

“You could’ve offered the girl a warm place to sleep,” Jack said. “It’s pretty clear Hope didn’t get that old cabin straight for her.”

“Don’t feel up to company,” he said. Then Doc lifted his gaze to Jack’s face. “Seems you’re more interested than me, anyway.”

“Didn’t really look like she’d trust anyone around here at the moment,” Jack said. “Cute little thing, though, huh?”

“Can’t say I noticed,” he said. He took a sip and then said, “Didn’t look like she had the muscle for the job, anyway.”

Jack laughed, “Thought you didn’t notice?” But he had noticed. She was maybe five-three. Hundred and ten pounds. Soft, curling blond hair that, when damp, curled even more. Eyes that could go from kind of sad to feisty in an instant. He enjoyed that little spark when she had snapped at him that she didn’t feel particularly humorous. And when she took on Doc, there was a light that suggested she could handle all kinds of things just fine. But the best part was that mouth—that little pink heart-shaped mouth. Or maybe it was the fanny.

“Yeah,” Jack said. “You could’ve cut a guy a break and been a little friendlier. Improve the scenery around here.

Two

When Mel and Mrs. McCrea returned to the cabin, it had warmed up inside. Of course, it hadn’t gotten any cleaner. Mel shuddered at the filth and Mrs. McCrea said, “I had no idea, when I talked to you, that you were so prissy.”

“Well, I’m not. A labor and delivery unit in a big hospital like the one I came from is pretty unglamorous.” And it struck Mel as curious that she had felt more in control in that chaotic, sometimes horrific environment than in this far simpler one. She decided it was the apparent deception that was throwing her for a loop. That and the fact that however gritty things got in L&D, she always had a comfortable and clean house to go home to.

Hope left her in possession of pillows, blankets, quilts and towels, and Mel decided it made more sense to brave the dirt than the cold. Retrieving only one suitcase from her car, she put on a sweatsuit, heavy socks, and made herself a bed on the dusty old couch. The mattress, stained and sagging, looked too frightening.

She rolled herself up in the quilts like a burrito and huddled down into the soft, musty cushions. The bathroom light was left on with the door pulled slightly closed, in case she had to get up in the night. And thanks to two brandies, the long drive and the stress of spoiled expectations, she fell into a deep sleep, for once not disturbed by anxiety or nightmares. The softly drumming rain on the roof was like a lullaby, rocking her to sleep. With the dim light of morning on her face, she woke to find she hadn’t moved a muscle all night, but lay swaddled and still. Rested. Her head empty.

It was a rare thing.

Disbelieving, she lay there for a while. Yes, she thought. Though it doesn’t seem possible under the circumstances, I feel good. Then Mark’s face swam before her eyes and she thought, what do you expect? You summoned it!

She further thought, there’s nowhere you can go to escape grief. Why try?

There was a time she had been so content, especially waking up in the morning. She had this weird and funny gift—music in her head. Every morning, the first thing she noticed was a song, clear as if the radio was on. Always a different one. Although in the bright light of day Mel couldn’t play an instrument or carry a tune in a bucket, she awoke each morning humming along with a melody. Awakened by her off-key humming, Mark would raise up on an elbow, lean over her, grinning, and wait for her eyes to pop open. He would say, “What is it today?”

“‘Begin the Beguine,’” she’d answer. Or, “‘Deep Purple.’” And he’d laugh and laugh.

The music in her head went away with his death.

She sat up, quilts wrapped around her, and the morning light emphasized the dirty cabin that surrounded her. The sound of chirping birds brought her to her feet and to the cabin’s front door. She opened it and greeted a morning that was bright and clear. She stepped out onto the porch, still wrapped in her quilts, and looked up—the pines, firs and ponderosa were so tall in daylight—rising fifty to sixty feet above the cabin, some considerably taller. They were still dripping from a rain that had washed them clean. Green pinecones were hanging from branches—pinecones so large that if a green one fell on your head, it might cause a concussion. Beneath them, thick, lush green fern—she counted four different types from wide-branched floppy fans to those as delicate as lace. Everything looked fresh and healthy. Birds sang and danced from limb to limb, and she looked into a sky that was an azure blue the likes of which she hadn’t seen in Los Angeles in ten years. A puffy white cloud floated aimlessly above and an eagle, wings spread wide, soared overhead and disappeared behind the trees.

She inhaled a deep breath of the crisp spring morning. Ah, she thought. Too bad the cabin, town and old doctor didn’t work out, because the land was lovely. Unspoiled. Invigorating.

She heard a crack and furrowed her brow. Without warning the end of the porch that had been sagging gave out completely, collapsing at the weak end which created a big slide, knocking her off her feet and splat! Right into a deep, wet, muddy hole. There she lay, a filthy, wet, ice cold burrito in her quilt. “Crap,” she said, rolling out of the quilt to crawl back up the porch, still attached at the starboard end. And into the house.

She packed up her suitcase. It was over.

At least the roads were now passable, and in the light of day she was safe from hitting a soft shoulder and sinking out of sight. Reasoning she wouldn’t get far without at least coffee, she headed back toward the town, even though her instincts told her to run for her life, get coffee somewhere down the road. She didn’t expect that bar to be open early in the morning, but her options seemed few. She might be desperate enough to bang on the old doctor’s door and beg a cup of coffee from him, though facing his grimace again wasn’t an inviting thought. But the doc’s house looked closed up tighter than a tick. There didn’t seem to be any action around Jack’s or the store across the street, but a complete caffeine junkie, she tried the door at the bar and it swung open.

The fire was lit. The room, though brighter than the night before, was just as welcoming. It was large and comfortable—even with the animal trophies on the walls. Then she was startled to see a huge bald man with an earring glittering in one ear come from the back to stand behind the bar. He wore a black T-shirt stretched tight over his massive chest, the bottom of a big blue tattoo peeking out beneath one of the snug sleeves. If she hadn’t gasped from the sheer size of him, she might’ve from the unpleasant expression on his face. His dark bushy brows were drawn together and he braced two hands on the bar. “Help you?” he asked.

“Um… Coffee?” she asked.

He turned around to grab a mug. He put it on the bar and poured from a handy pot. She thought about grabbing it and fleeing to a table, but she frankly didn’t like the look of him, didn’t want to insult him, so she went to the bar and sat up on the stool where her coffee waited. “Thanks,” she said meekly.

He just gave a nod and backed away from the bar a bit, leaning against the counter behind him with his huge arms crossed over his chest. He reminded her of a nightclub bouncer or bodyguard. Jesse Ventura with attitude.