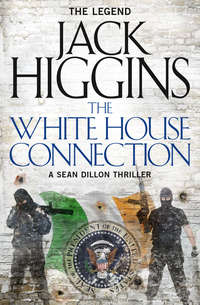

The White House Connection

‘Well, I’m your man. Will Irish do?’

‘Why not?’

He was back in a few moments with two glasses. She put hers down, got out her silver case and held it out. ‘Do you indulge?’

‘Jesus, but you’re a wonderful woman.’ His old Zippo flared and he gave her a light.

‘Do you mind if I say something, Mr Dillon?’ she said. ‘You’re wearing a Guards tie.’

‘Ah, well, I like to keep old Ferguson happy.’

She took a chance. ‘I should mention that I know about you, Mr Dillon. My old friend Tony Emsworth told me everything, and for very special reasons.’

‘Your son, Lady Helen.’ Dillon nodded. ‘I’m surprised you’d speak to me.’

‘I believe war should still have rules, and from what Tony told me, you were an honourable man, however ruthless and, may I say, misguided.’

‘I stand corrected.’

He bowed his head in mock humility. She said, ‘You rogue. You can get me that champagne now, only make sure they open a decent bottle.’

‘At your command.’

He joined Ferguson at the bar. ‘Lady Helen,’ he said. ‘Quite a woman.’

‘And then some.’

The barman poured the champagne into two glasses. ‘There’s something about her, something special. Can’t put my finger on it.’

‘Don’t try, Dillon,’ Ferguson told him. ‘She’s far too good for you.’

It was a week later that they flew from Gatwick to New York in one of her company’s Gulfstreams, and stayed at the Plaza. By that time, she knew the file backwards, every facet of every individual in it, and had also used every facility available in the company’s computer. She had the Colt .25 with her. In all her years flying in the Gulfstreams, she had never been checked by security once.

She knew everything. For example, that Martin Brady, the Teamsters’ Union official, attended a union gym near the New York docks three times a week, and usually left around ten in the evening. Hedley took her to a place a block away, then she walked. Brady had a red Mercedes, a distinctive automobile. She waited in an alley next to where he had parked it, and slipped out only to shoot him in the back of the neck as he leaned over to unlock the Mercedes.

That had been Hedley’s suggestion. He’d heard that the mob preferred such executions with a small calibre pistol, usually a .22, but a .25 would do, and this would make the police think they had a mob-versus-union problem.

Thomas Cassidy, with a fortune in Irish theme pubs, was easy. He’d recently opened a new place in the Bronx and parked in an alley at the rear. She checked it out two nights running and got him on the third, at one in the morning, once again as he unlocked his car. According to The New York Times, there had been a protection racket operating in the area and the police thought Cassidy a victim. She’d known about all that and his complaints to the police from the computer.

Patrick Kelly, the boss of the construction firm, was even easier. He had a house in Ossining, with countryside all around. His habit was to rise at six in the morning and run five miles. She checked out his usual route, then caught him on the third morning, running with the hood of his track suit up against heavy rain. She stood under a tree as he approached, shot him twice in the heart, then removed the gold Rolex watch from his wrist and the chain from around his neck, again at Hedley’s suggestion. A simple mugging, was all.

So, everything worked perfectly. She hadn’t needed the pills as much, and Hedley, in spite of his doubts, had proved a rock. Am I truly wicked, she would ask herself, really evil? And then recalled reading that in Judaism, Jehovah was not personally responsible for many actions. He employed angels, an Angel of Death, for example.

Is that me? she asked herself. But needing justice, she could not be sorry. So she continued until that rainy night in Manhattan, when she waited for Senator Michael Cohan to come home from the Pierre and was sidetracked.

At the same time that Helen Lang was returning to the Plaza, consoling herself with the thought that she would get Cohan in London, other events were taking place there that would prove to have a profound influence not only on her, but on others she already knew.

A few hours after Lady Helen went to bed, Hannah Bernstein entered Charles Ferguson’s office at the Ministry of Defence, Dillon behind her.

‘Sorry to bother you, sir, but we’ve got a hot one.’

‘Really?’ He smiled. ‘Tell me.’

She nodded to Dillon, who said, ‘There’s an old mate of mine, Tommy McGuire, Irish-American. Been into arms dealing for years. He was caught with a defective brake light in Kilburn last night, and a rather keen young woman probationer insisted on checking the boot of his car.’

‘Surprise, surprise,’ Hannah Bernstein said. ‘Fifty pounds of Semtex and two AK47s.’

‘How delicious,’ Ferguson replied. ‘With his record, which I’m sure he has, that should draw ten years.’

‘Except for one thing,’ Hannah told him. ‘He says he wants a deal.’

‘Really.’

‘He says he can give us Jack Barry,’ Dillon told him.

Ferguson went very still, frowning. ‘Where is McGuire?’

‘Wandsworth,’ Hannah said, naming one of London’s bleaker prisons.

‘Then let’s go and see what he has to say,’ and Charles Ferguson stood up.

Wandsworth Prison was one of the toughest in the country, what was known as a hard nick. Ferguson saw the governor and served him with the kind of warrant that made that good man sit up. No one was to see McGuire except those designated by Ferguson, not even Scotland Yard’s anti-terrorist section, and certainly not anybody from Military Intelligence in Northern Ireland or the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Any deviation from such a ruling could have sent the governor himself to prison for breaching the Official Secrets Act.

Ferguson, Hannah Bernstein and Dillon waited in an interview room and a prison officer delivered McGuire and withdrew on Ferguson’s nod. McGuire almost had a fit when he saw Dillon.

‘Jesus, Sean, it’s you.’

‘As ever was.’ Dillon offered him a cigarette and said to the others, ‘Tommy and I go back a long way. Beirut, Sicily, Paris.’

‘IRA, of course,’ Ferguson said.

‘Not really. Tommy was never one for direct action, but if there was a pound or two in it, he could get you anything. Automatic weapons, Semtex, rocket launchers. Got away with a lot because of his Yank passport and the fact that he always acted as an agent for foreign arms firms. German, French.’ He gave McGuire a light. ‘Still fronting for old Jobert out of Marseilles, but then you would. He has the Union Corse protecting him.’ He turned to Hannah. ‘Worse than the Mafia, that lot.’

‘I know who they are, Dillon.’ She looked at McGuire with total contempt. ‘Two AK47s and fifty pounds of Semtex were found in your car last night. Samples, I presume? Who were you going to see?’

‘No, you’ve got it wrong,’ McGuire told her. ‘I mean, I didn’t know they were there. I was told there would be a car waiting for me at Heathrow when I got in. The key under the mat. It must have been a setup.’

Ferguson said coldly, ‘We’ll leave now.’

‘Okay, okay,’ McGuire said. ‘You were right about the stuff in the car being samples. They were from Jobert to Tim Pat Ryan. When I flew in, I phoned to arrange the meet and discovered he was dead.’

‘Indeed he is,’ Ferguson said. ‘But there was some mention of Jack Barry.’

McGuire hesitated. ‘Barry used Tim Pat Ryan as a front man in London. It was Ryan who fixed things up. I can give you Jack Barry. I swear it. Just listen.’

‘Get on with it, then.’

Hannah said, ‘So you know Jack Barry?’

‘No. I’ve never met him.’

‘Then why are you wasting our time?’

‘Let me,’ Dillon said and offered McGuire another cigarette. ‘You’ve never met Jack Barry? That’s good, because I have, and he’d cut your balls off for fun if you crossed him. Let me speculate. Jack inherited the Sons of Erin from dear old Frank Barry, alas no longer with us. The Sons of Erin would kill the Pope, which isn’t surprising as our Jack is one of the few Protestants in the IRA. However, he’s had a falling-out with Dublin, Sinn Fein and the peace process. Probably thinks they’re a bunch of old women.’

‘So I hear.’

‘So let me speculate again. His source of arms from Dublin has dried up. However, there’s family money in his background, he’s rich in his own right, so he’s dealing direct with Jobert. Semtex, guns, whatever, and you’re the middle man. Ryan was in London, but, alas, no more.’

‘That’s right,’ McGuire said eagerly. ‘I’m supposed to meet Barry in Belfast in three days.’

‘Really?’ Ferguson said. ‘Where exactly?’

‘I’m to book in at the Europa Hotel and wait. He’ll send for me when he’s ready.’

‘Send for you where?’ Hannah Bernstein asked.

‘How the hell would I know? I’ve already told you, I’ve never even met the guy.’

The room went very still. Ferguson said, ‘Is that really true?’

‘Of course it is.’

Ferguson stood up. ‘Serve the warrant on the prison governor, Chief Inspector. Deliver the prisoner to the Holland Park safe house.’

She pressed the bell and the prison officer entered. ‘Take him back to his cell and get him ready to leave.’

McGuire said, ‘Have we got a deal?’ but the prison officer was already hauling him out.

Dillon said, ‘Are you thinking what I am, you old bugger?’

‘You must admit it would be a wonderful sting,’ the Brigadier said. ‘When is McGuire not McGuire? This could lead us directly to Barry and, oh, how I’d love to lay hands on that one.’

‘There is one thing, sir,’ Hannah Bernstein said. ‘McGuire is an American and it’s too easy to spot a phoney American accent. Who are we going to get to play him? We need someone who can pass as American and who can handle himself.’

Ferguson said, ‘That’s a good point. In fact, it would seem to me there’s an American dimension to all this. I mean, the President wouldn’t be too happy to find out in the middle of peace negotiations for Ireland that there was an American citizen trying to sell arms to one of the worst terrorists in the business.’

Dillon, devious as usual, was ahead of him. ‘Are you suggesting that I speak to Blake Johnson?’

It was Hannah who said, ‘Well, that’s what the Basement is for, sir.’

‘Who knows?’ Dillon said. ‘Blake might feel like a holiday in Ireland. Who better to play an American than an American – especially one who can shoot a fly at twenty paces?’

‘Sometimes you really do get it right, Dillon.’ Ferguson smiled. ‘Now let’s get out of this dreadful place.’

Blake Johnson was still a handsome man at fifty, and looked younger. A Marine at nineteen, he’d left Vietnam with a Silver Star, a Vietnamese Cross of Valor and two Purple Hearts. A law degree at the University of Georgia had taken him into the FBI. When President Jake Cazalet had been a Senator and subject to right-wing threats, Blake had managed to get to him when a police escort had lost him, shot two men trying to assassinate him, and taken a bullet himself.

It had led to a special relationship with the man who became President, and an appointment as Director of the General Affairs Department at the White House, a cloak for the President’s private investigation squad, the Basement. Already during the present administration, Johnson had proved his worth, had engaged in a number of black operations, some of which had involved Ferguson and Dillon.

It was hot that afternoon, when Blake arrived at the Oval Office and found the President signing papers with his chief of staff, Henry Thornton. Blake liked Thornton, which was a good thing, because Thornton basically ran the place. It was his job to make sure the White House ran smoothly, that the President’s programmes were advancing through Congress, that the President’s image was protected. The pay was no big deal, but it was the ultimate prestige job. Besides, Thornton had enough money from running the family law firm in New York before joining the President in Washington.

Thornton was one of the few men who knew the true purpose of the Basement. He looked up and smiled. ‘Hey, Blake, you look thoughtful.’

‘As well I might,’ Blake said.

Cazalet sat back. ‘Bad?’

‘Let’s say tricky. I’ve had an interesting conversation with Charles Ferguson.’

‘Okay, Blake, let’s hear the worst.’

When Blake was finished, the President was frowning and so was Thornton. Cazalet said, ‘Are you seriously suggesting you go to Belfast, impersonate this McGuire and try to take Barry on his own turf?’

Blake smiled. ‘I haven’t had a vacation for a while, Mr President, and it would be nice to see Dillon again.’

‘Dear God, Blake, no one admires Dillon more than I do. The service you and he did for me – rescuing my daughter from those terrorists – I’ll never forget that. But this? You’re going into the war zone.’

Thornton said, ‘Think about it, Blake. You’d be going into harm’s way and is it really necessary?’

Blake said, ‘Gentlemen, we’ve worked our rocks off for peace in Northern Ireland. Sinn Fein have tried, the Loyalists have talked, but again and again it’s these terrorist splinter groups on both sides who keep things going. This man, Jack Barry, is a bad one. I must remind you, Mr President, that he is also an American citizen, a serving officer in Vietnam who was eased out for offences that can only be described as murder. He’s been a butcher for years, and he’s our responsibility as much as theirs. I say take him out.’

Jake Cazalet was smiling. He looked up at Thornton, who was smiling too.

‘You obviously feel strongly about this, Blake.’

‘I sure as hell do, Mr President.’

‘Then try and come back in one piece. It would seriously inconvenience me to lose you.’

‘Oh, I’d hate to do that, Mr President.’

In London in his office at the Ministry of Defence, Ferguson put down the red secure phone and touched the intercom button.

‘Come in.’

A moment later, Dillon and Hannah Bernstein entered.

‘I’ve spoken to Blake Johnson. He’ll be at the Europa Hotel the day after tomorrow, booked in as Tommy McGuire. You two will join him.’

‘What kind of backup will we have, sir?’ Hannah asked.

‘You’re the backup, Chief Inspector. I don’t want the RUC in this or Army Intelligence from Lisburn. Even the cleaning women are nationalists there. Leaks all over the place. You, Dillon and Blake Johnson must handle it. You only need one pair of handcuffs for Barry.’

It was Dillon who said, ‘Consider it done, Brigadier.’

‘Can you guarantee that?’

‘As the coffin lid closing.’

4

As frequently happened in Belfast, a cold north wind drove rain across the city, stirring the waters of Belfast Lough, rattling the windows of Dillon’s room at the Europa, the most bombed hotel in the world. He looked out over the railway station, remembering the extent to which this city had figured in his life. His father’s death all those years ago, the bombings, the violence. Now the powers that be were trying to end all that.

He reached for the phone and called Hannah Bernstein in her room. ‘It’s me. Are you decent?’

‘No. Just out of the shower.’

‘I’ll be straight round.’

‘Don’t be stupid, Dillon. What do you want?’

‘I phoned the airport. There’s an hour’s delay on the London plane. I think I’ll go down to the bar. Do you fancy some lunch?’

‘Sandwiches would do.’

‘I’ll see you there.’

It was shortly after noon, the Library Bar quiet. He ordered tea, Barry’s tea, Ireland’s favourite, and sat in the corner reading the Belfast Telegraph. Hannah joined him twenty minutes later, looking trim in a brown trouser suit, her red hair tied back.

He nodded his approval. ‘Very nice. You look as if you’re here to report on the fashion show.’

‘Tea?’ she said. ‘Sean Dillon drinking tea, and the bar open. That I should live to see the day.’

He grinned and waved to the barman. ‘Ham sandwiches for me, this being Ireland. What about you?’

‘Mixed salad will be fine, and tea.’

He gave the barman the order and folded the newspaper. ‘Here we are again then, sallying forth to help solve the Irish problem.’

‘And you don’t think we can?’

‘Seven hundred years, Hannah. Any kind of a solution has been a long time coming.’

‘You seem a little down.’

He lit a cigarette. ‘Oh, that’s just the Belfast feeling. The minute I’m back, the smell of the place, the feel of it, takes over. It will always be the war zone to me. The bad old days. I should go and see my father’s grave, but I never do.’

‘Is there a reason, do you think?’

‘God knows. My life was set, the Royal Academy, the National Theatre, you’ve heard all that, and I was only nineteen.’

‘Yes, I know, the future Laurence Olivier.’

‘And then my old man came home and got knocked off by Brit paratroops.’

‘Accidentally.’

‘Sure, I know all that, but when you’re nineteen you see things differently.’

‘So you joined the IRA and fought for the glorious cause.’

‘A long time ago. A lot of dead men ago.’

The food arrived. A young waitress served them and left. Hannah said, ‘And looking back, it’s regrets time, is it?’

‘Ah, who knows? By this time, I could have been a leading man with the Royal Shakespeare Company. I could have been in fifteen movies.’ He wolfed down a ham sandwich and reached for another. ‘I could have been famous. Didn’t Marlon Brando say something like that?’

‘At least you’re infamous. You’ll have to content yourself with that.’

‘And there’s no woman in my life. You’ve spurned me relentlessly.

‘Poor man.’

‘No kith or kin. Oh, more cousins in County Down than you could shake a stick at, and they’d run a mile if I appeared on the horizon.’

‘They would, wouldn’t they, but enough of this angst. I’d like to know more about Barry.’

‘I knew his uncle, Frank Barry, better. He taught me a lot in the early days, until we had a falling out. Jack was always a bad one. Vietnam was his proving ground and the murder of Vietcong prisoners the reason the army kicked him out. All these years of the Troubles, he’s gone from bad to worse. Another point, as you’ve read in his file, he’s often been a gun for hire for various organizations around the world.’

‘I thought that was you, Dillon.’

He smiled. ‘Touché. The hard woman you are.’

Blake Johnson entered the Library Bar at that moment. He wore black Raybans, a dark blue shirt and slacks, a grey tweed jacket. The black hair, touched by grey, was tousled. He gave no sign of recognition and moved to the bar.

‘Poor sod. He looks as if he’s been travelling,’ Dillon said.

‘I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, Dillon, you’re a bastard.’ She stood up. ‘Let’s go and wait for him.’

Dillon called to the barman, ‘Put that on room fifty-two,’ and followed her out.

Rain rattled against the window as Dillon got a half-bottle of champagne from the fridge and opened it. ‘The usual Belfast weather, but what can you expect in March?’ He filled three glasses, and took one himself. ‘Good to see you, Blake.’

‘And you, my fine Irish friend.’ Blake toasted him and turned to Hannah. ‘Chief Inspector. More fragrant than ever.’

‘Hey, I’m the one who gets to make remarks like that,’ Dillon said. ‘Anyway, let’s get down to it.’

They all sat. Blake said, ‘I’ve read the file on Barry. He’s a bad one. But I’d like to hear your version, Sean.’

‘It was his uncle I knew first, Frank Barry. He founded the Sons of Erin, a rather vicious splinter group from the beginning. He was knocked off a few years ago, but that’s another story. Jack’s been running things ever since.’

‘And you know him?’

‘We’ve had our dealings over the years, exchanged shots. I’m not his favourite person, let’s put it that way.’

‘And we’re certain that he hasn’t met McGuire?’

‘So McGuire says,’ Hannah told him. ‘And why would he lie? He wants an out.’

‘Fine. I’ve memorized all that stuff you sent on the computer. McGuire’s past, this French outfit he works for, Jobert and Company, and this Tim Pat Ryan who nearly finished you off in London, Sean. Intriguing that – a woman as executioner. But as for Barry – I’d like to hear about him from you, everything, even if it is on file.’

Dillon complied and talked at length. After a while, Blake nodded. ‘That’s about it then. I’m going to need my wits about me with this one.’

‘There’s one more thing you should know about the Barrys. First of all, they’re an old Protestant family.’

‘Protestant?’ Blake was incredulous.

‘It’s not so unusual,’ Dillon said. ‘There are plenty of Protestant nationalists in Irish history. Wolfe Tone, for example. But in addition to that, his great-uncle was Lord Barry, which made Frank Barry the heir, except that he’s dead, as you know.’

‘Are you trying to tell me Jack Barry is the heir apparent?’ Blake asked.

‘His father was Frank’s younger brother, but he died years ago, which only leaves Jack.’

‘Lord Barry?’

‘Frank didn’t claim the title, and Jack certainly hasn’t. It would give the Queen and the Privy Council problems,’ Hannah told him.

‘I just bet it would,’ Blake said.

‘But Jack takes it seriously.’ Dillon nodded. ‘An old family, the Barrys. Lots of history there. There’s a family estate and castle, Spanish Head, on the coast, about thirty miles north of Belfast. It’s owned by the National Trust now. Jack used to rhapsodize about it years ago. So – our Jack’s a complicated man. Anyway, let’s get down to it. McGuire is to wait in the bar between six and seven for a message that his taxi is ready.’

‘Destination unknown?’

‘Of course. I figure he’ll be waiting somewhere in the city, with lots of ways out in case of trouble. The dock area, for example.’

‘And you’ll follow?’

‘That’s the idea. Green Land Rover.’ Dillon passed him a piece of paper. ‘That’s the number.’

‘And what if you lose me?’

‘It’s not possible.’ Hannah Bernstein put a black briefcase on the table and opened it. ‘We’ve got a Range Finder in here.’

‘Follow you anywhere: The very latest,’ Dillon told him.

The Range Finder was a black box with a screen. ‘Watch this,’ Hannah said, and pressed a button. A section of city streets appeared. ‘The whole of Northern Ireland’s in there.’

‘Very impressive,’ Blake told her.

‘Even more so with this.’ She opened a small box and took out a gold signet ring. ‘I hope it fits. If not, I’ve got another bug that you can pin anywhere you want.’

Blake tried the ring on his left hand, and nodded. ‘Feels good to me.’

‘No weapon,’ Dillon said. ‘There’s no way of fooling Barry’s people in that respect.’

‘Then you’d better be right behind me.’

‘Oh, we’ll be there and armed to the teeth.’

‘So the general idea is I lead you to Barry and you jump him? No police, no backup?’

‘This is a black one, Blake. We snatch the bastard, stick a hypo in him and get him to the airport, where a Lear jet will take us to Farley Field.’

‘And afterwards?’

‘Our Holland Park safe house in London, where the Brigadier will have words,’ Hannah put in.

‘Grand drugs they have these days,’ Dillon said. ‘He’ll be telling all before you know it, although the Chief Inspector doesn’t like that bit.’

‘Shut up, Dillon,’ she said fiercely.

Blake nodded. ‘No need to argue, you two. I’m happy to be here and the President’s happy. No problem. I’m in your hands and that’s good enough for me.’

The Library Bar was a popular watering hole for those in business who liked a drink before going home, and was quite busy when Blake went in just after six. Blake sat at the bar, ordered a whisky and soda and lit a cigarette. Tense, but in control. For one thing, he had enormous faith in Dillon. It got to six-thirty. He ordered another small whisky, and as the barman brought it to him, a porter came in with a board saying McGuire.