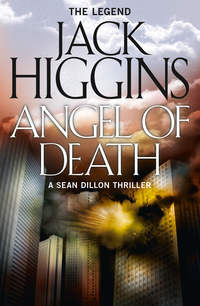

Angel of Death

Ashimov turned. ‘What do you want?’

‘You, actually,’ Rupert Lang said, and shot him twice in the heart, the silenced Beretta making only a slight coughing sound. He leaned down and put another bullet between Ashimov’s eyes then put the Beretta in his raincoat pocket, moved rapidly across the gardens to Queen’s Gate, crossed to the Albert Hall and walked on for a good half mile before hailing a cab and telling the driver to take him to Westminster.

He lit a cigarette and sat back, shaking with excitement. He had never felt like this in his life before, not even in the Paras in Ireland. Every sense felt keener, even the colours when he looked out at the passing streets seemed sharper. But the excitement, the damned excitement!

He closed his eyes. ‘My God, old sport, what’s happening to you?’ he murmured.

He arrived at the St Stephen’s entrance to the Commons, went through the Central Lobby to his office and got rid of his umbrella and raincoat and put the Beretta in his safe, then went down to the entrance to the House and passed the bar. There was a debate taking place on some social services issue. He took his usual seat on the end of one of the aisles. When he looked up he saw Tom Curry seated in the front row of the Strangers’ Gallery, his left arm in a sling. Lang nodded up to him, folded his arms and leaned back.

Half an hour later the Times newsdesk received a brief message by telephone in which January 30 claimed credit for the assassination of Colonel Boris Ashimov.

In the three years that followed, Curry maintained a steady flow of confidential information of every description, aided by Lang. They made only three hits during the period. Two of these took place at the same time – a couple of IRA bombers released from trial at the Old Bailey on a legal technicality. The two men proceeded on a drunken spree that lasted all day. It was Curry who charted their progress until midnight, then called in Lang, who killed them both as they sat, backs to the wall, in a drunken stupor in a Kilburn alley.

The third was a CIA field officer attached to the American Embassy’s London Station. He had been giving Belov considerable aggravation and, after the Berlin Wall came down, appeared to be far too friendly with the Russian’s latest rival, Mikhail Shimko, who had replaced Ashimov as Colonel in Charge of London Station KGB.

The CIA man was called Jackson, and by chance, his name came up at one of the joint intelligence working parties. News had come in that he was having a series of meetings at an address in Holland Park with members of a Ukrainian faction resident in London. Curry kept a watch at the appropriate times and noticed that Jackson always walked for a mile afterwards, following the same route through quiet streets to the main road where he would hail a taxi.

After the next meeting, Lang was waiting in a small Ford van – provided by Belov, of course – at an appropriate point on the route. As Jackson passed, Lang, wearing a knitted ski mask in black, stepped out and shot him once in the back, penetrating the heart. He finished him with a head shot, got in the van and drove away. He left the van in a builders’ yard in Bayswater, as instructed by Belov, and walked away, whistling softly to himself.

It was half an hour later that a young reporter on the newsdesk of the Times took the phone call claiming credit for the killing by January 30.

The British Government allowed the Americans to flood London temporarily with CIA agents intent on hunting down Jackson’s killer. As usual, they drew a complete blank. That the killings claimed by January 30 from Ali Hamid onwards had been the work of the same Beretta 9-millimetre was known to everyone, as was the significance of January 30. The Bloody Sunday connection should have indicated an Irish revolutionary connection, but even the IRA got nowhere in their investigations. In the end, the CIA presence was withdrawn.

British Army Intelligence, Scotland Yard’s anti-terrorist department, MI5, all failed to make headway. Even the redoubtable Brigadier Charles Ferguson, head of the special intelligence unit responsible to the Prime Minister, could only report total failure to Downing Street.

It was in January 1990, following the collapse of the Communist-dominated government of East Germany, that Lang and Curry attended a cultural evening at the American Embassy. There were at least a hundred and fifty people there, including Belov, whom they found at the champagne bar. They took their glasses into an anteroom and found a corner table.

‘So, everything is falling apart for you people, Yuri,’ Lang said. ‘First the Wall comes tumbling down, now East Germany folds and a little bird tells me there’s a strong possibility that your Congress of People’s Deputies might soon abolish the Communist Party’s monopoly of power in Russia.’

Belov shrugged. ‘Disorder leads to strength. It’s inevitable. Take the German situation. West Germany is at present the most powerful country in Western Europe economically. The consequences of taking East Germany on board will be catastrophic in every way and particularly economically. The balance of power in Europe will once again be altered totally. Remember what I said a long time ago? Chaos is our business.’

‘I suppose you’re right when you come to think of it,’ Lang said.

Curry nodded. ‘Of course he is.’

‘I invariably am.’ Belov raised his glass. ‘To a new world, my friends, and to us. One never knows what’s round the corner.’

‘I know,’ Rupert Lang said. ‘That’s what makes it all so damned exciting.’

They touched glasses and drank.

4

Rupert Lang was more right than he knew. There was something round the corner, something profound and disturbing that was to affect all three of them, although it was not to take place until the Gulf War was over and done with. January, 1992 to be precise.

Grace Browning was born in Washington in 1965. Her father was a journalist on the Washington Post, her mother was English. When she was twelve tragedy struck, devastating her life. On the way home from a concert one night, her parents’ car was rammed into the kerb by an old limousine. The men inside were obviously on drugs. Afterwards, she remembered the shouting, the demands for money, her father opening the door to get out and then the shots, one of which penetrated the side window at the rear and killed her mother instantly.

Grace lay in the bottom of the car, frozen, terrified, glancing up only once to see the shape of a man, gun raised, shouting, ‘Go, go, go!’ and then the old limousine shot away.

She wasn’t even able to give the police a useful description, couldn’t even say whether they were white or black. All that mattered was that her father died the following morning and she was left alone.

Not quite alone, of course, for there was her mother’s sister, her Aunt Martha – Lady Hunt to be precise – a woman of considerable wealth, widowed young, who lived in some splendour in a fine town house in Cheyne Walk in London. She had received her niece with affection and firmness, for she was a tough, practical lady who believed you had to get on with it instead of sitting down and crying.

Grace was admitted to St Paul’s Girls’ School, one of the finest in London, where she soon proved to have a sharp intelligence. She was popular with everyone, teachers and pupils alike, and yet for her, it was a sort of performance. Inside she was one thing, herself, detached, cold; but on the surface she was charming, intelligent, warm. It was not surprising that she was something of a star in school drama circles.

Her social life, because of her aunt, was conducted at the highest level: Cannes and Nice in the summer, Barbados in the winter, always a ceaseless round of parties on the London scene. When she was sixteen, like most of the girls she knew, she attempted her first sexual encounter, a gauche 17-year-old public schoolboy. It was less than rewarding and as he climaxed, a strange thing happened. She seemed to see in her head the shadowy figure of the man who had killed her parents, gun raised.

When the time came for Grace to leave school, although her academic grades were good enough for Oxford or Cambridge, she had only one desire – to be a professional actor. Her aunt, being the sort of woman she was, supported her fully, stipulating only that Grace had to go for best. So Grace auditioned for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and they accepted her at once.

Her career there was outstanding. In the final play, Macbeth, she played Lady Macbeth, absurdly young and yet so brilliant that London theatrical agents clamoured to take her on board. She turned them all down and went to Chichester, the smallest of the two theatres, the Minerva, to play the lead in a revival of Anna Christie – so triumphantly that the play transferred to the London West End, the Theatre Royal at the Haymarket, where it ran for a year.

After that, she could have everything, the Royal Shakespeare Company, the National Theatre, establishing herself in a series of great classic roles. She went to Hollywood only once to star in a classy and flashy revenge thriller in which she killed several men, but she turned down all subsequent film offers except for the occasional TV appearance and returned to the National Theatre.

Money, of course, was no problem. Aunt Martha saw to that and took great pride in her niece’s achievements. She was the one person Grace felt loved her and she loved her fiercely in return, dropping out of the theatre totally for the last, terrible year when leukaemia took its hold on the old woman.

Martha came home at the end to die in her own bed, in the room that overlooked the Thames. There was medical help in abundance, but Grace looked after her every need personally.

On the last evening it was raining, beating softly against the windows. She was holding her aunt’s hand and Martha, gaunt and wasted, opened her eyes and looked at her.

‘You’ll go back now, promise me, and show them all what real acting is about. It’s what you are, my love. Promise me.’

‘Of course,’ Grace said.

‘No sad tears, no mourning. A celebration to prove how worthwhile it’s been.’ She managed a weak smile. ‘I never told you, Grace, but your father always believed the family tradition that they were kin to Robert Browning.’

‘The poet?’ Grace asked.

‘Yes. There’s a line in one of his great poems. “Our interest’s on the dangerous edge of things.” I don’t know why, but it seems to suit you perfectly.’

Her eyes closed and she died a few minutes later.

She was wealthy now, the house in Cheyne Walk was hers and the world of theatre was her oyster, but no one could control her, no one could hold her. Her wealth meant that she could do what she wanted. Her first role on her return was in Look Back in Anger with an obscure South Coast repertory company in a seaside town. The critics descended from London in droves and were ecstatic. After that she did a range of similar performances at various provincial theatres, finally returning to the National Theatre to do Turgenev’s A Month in the Country.

No long-term contracts, no ties. She had set a pattern. If a part interested her she would play it – even if it was for four weeks at some obscure civic theatre in the heart of Lancashire or some London fringe theatre venue such as the King’s Head or the Old Red Lion – and the audiences everywhere loved her.

Love in her own life was a different story. There were men, of course, when the mood came, but no one who ever moved her. In male circles in the theatre she was known as the Ice Queen. She knew this but it didn’t dismay her in the slightest, amused her if anything and her actor’s gift for analysis of a role told her that if anything, she had a certain contempt for men.

In October 1991, Grace performed in Brendan Behan’s The Hostage at the Minerva Studio at Chichester, still her favourite theatre. It was a short run, but such was the interest in this most Irish of plays that the company was invited to the Lyric Theatre, Belfast, for a two-week run. Unfortunately, Grace was scheduled to start rehearsals at the National for A Winter’s Tale immediately after her stint at the Minerva, and so the director of The Hostage came to see her in some trepidation.

‘The Lyric, Belfast, would like us for two weeks. Of course, I’ll have to say no. I mean, you start rehearsing Monday at the National.’

‘Belfast?’ she said. ‘I’ve never been. I like the sound of that.’

‘But the National?’ he protested.

‘Oh, they can put things on the back burner for a couple of weeks.’ She smiled, that famous smile of hers that seemed to be for you alone. ‘Or get someone else.’

She indulged herself by staying at the Europa Hotel. She stood at the window of her suite and looked out at the rain driving in across the city, suddenly excited to be here, surely one of the most dangerous cities in the world. It was only four o’clock and she was not due at the Lyric until six-thirty. On impulse, she went downstairs.

At the main entrance, the head doorman smiled. ‘A taxi, Miss Browning?’

Posters advertising the play with her photo on them were on a stand close by.

She gave him her best smile. ‘No, I just need some fresh air and I like the rain.’

‘Plenty of that in Belfast, miss, better take this,’ and he put up an umbrella for her.

She started towards the bus station and the Protestant stronghold of Sandy Row, feeling suddenly cheerful as a bitter east wind blew in from Belfast Lough.

Tom Curry always stayed at the Europa during his monthly visits as visiting Professor at Queen’s University. He liked Belfast, the sense of danger, the thought that anything might happen. Sometimes his visits coincided with Rupert Lang’s, for Lang was now an extra Under-Secretary of State at the Northern Ireland Office, which meant frequent visits to Ulster on Crown business, and this was one of them.

Lang arrived back at the Europa at five-thirty, went into the Library Bar and found Tom Curry seated at one end, reading the Belfast Telegraph, a Bushmills in front of him.

Curry glanced up. ‘Hello, old lad. Had a good day?’

‘It’s always bloody raining every time I come to Belfast.’ Lang nodded to the barman. ‘Same as my friend.’

‘You don’t like it much, do you?’ Curry said.

‘I went through hell here, Tom, back in seventy-three. Close to six hundred dead in one year. Bodies under the rubble for days, the stink of explosions. I can still smell it.’ He raised his glass. ‘To you, old sport.’

Curry toasted him back. ‘As the Fenians say, may you die in Ireland.’

‘Thanks very much.’ Lang smiled. ‘Mind you, you can’t fault them on their attitude to culture here.’ He nodded towards the wall behind the bar, where Grace’s poster was displayed.

‘Grace Browning, yes. She’s wonderful. Strange choice of a play for Belfast, though, The Hostage. Very IRA.’

‘Nonsense,’ Lang said. ‘Behan showed the absurdity of the whole thing even though he was in the IRA himself.’

At that moment Grace Browning entered. As she unbuttoned her raincoat, a waiter hurried to take it. She walked to the bar and Rupert Lang said, ‘Good God, it’s Grace Browning.’

Hearing him, she turned and gave him that famous smile. ‘Hello.’

‘May I introduce myself?’ he asked.

She frowned slightly. ‘You know, I feel I’ve met you before.’

Curry laughed. ‘No, you’ve occasionally seen him on the television. Under-Secretary of State at the Northern Ireland Office. Rupert Lang.’

‘I’m impressed,’ she said. ‘And you?’

‘Tom Curry,’ Lang said. ‘He’s just a Professor of Political Philosophy at London University. Visiting Professor here at Queen’s once a month. Can we offer you a drink?’

‘Why not. A glass of white wine. Just one, I’ve got to give a performance.’

Lang gave the order to the barman. ‘We’ve seen you many times.’

‘Together?’

‘Oh, yes,’ he smiled. ‘Tom and I go back a long way. Cambridge.’

‘That’s nice.’ She sipped her wine. There was something about them. She sensed it. Something unusual. ‘Are you coming to the show tonight?’

‘Didn’t realize it was on,’ Curry said. ‘I’m only here for three days. Don’t suppose there are any tickets left.’

‘I’ll leave you two of my tickets at the box office,’ she said.

It was a challenge instantly taken up. ‘Oh, you’re on,’ Lang said. ‘Wonderful.’

She swallowed the rest of the wine. ‘Good. Now I’ll have to love you and leave you. Hope you enjoy it.’

As she left the bar, Curry turned to Lang and they toasted each other. ‘By the way,’ Curry said, ‘are you carrying?’

‘Of course I am,’ Lang told him. ‘If you think I’m going to walk the streets of Belfast without a pistol you’re crazy. As a Minister of the Crown I have my permit, Tom. No problems with security at the airports.’

‘The Beretta?’ Curry asked.

‘But of course. Lucky for us, I’d say.’

Curry shook his head. ‘It’s just a game to you, isn’t it? A wild, exciting game.’

‘Exactly, old sport, but then life can be such a bore. Now drink up and let’s go and get ready.’

Grace Browning was wonderful, no doubt about it, receiving a rapturous reception from the packed house at the end of the play. Curry and Lang went into the bar for a drink and debated whether to go backstage and see her.

It was Lang who said, ‘I think not, old sport. Probably lots of locals doing exactly that. We’ll go back to the Europa and have a nightcap at the bar. She may well look in.’

‘You like her, don’t you?’ Curry said.

‘So do you.’

Curry smiled. ‘Let’s get the car.’

On their way back to the hotel, Curry, who was driving, turned into a quiet road between several factories and warehouses, deserted at night. Lang put a hand on his arm as they passed a woman walking rapidly along the pavement, an umbrella up against the rain.

‘Good God, it’s her.’

‘The damned fool,’ Curry said. ‘She can’t walk around the back streets of Belfast like that on her own.’

‘Pull in to the kerb,’ Lang said. ‘I’ll get her.’

Curry did so. Lang opened the car door and saw two young men in bomber jackets run up behind Grace Browning and grab her. He heard her cry out, and then she was hustled into an alley.

Grace wasn’t afraid, just angry with herself for having been such a fool. On a high after her performance, she’d thought that the walk back to the hotel in the rain would calm her down. She should have known better. This was uncharted territory. Belfast. The war zone.

They hustled her to the end of the alley, where there was a dead end, and a jumble of packing cases lay under an old streetlamp bracketed to a wall. She stood facing them.

‘What do you want?’

‘English, is it?’ The one with a ponytail laughed unpleasantly. ‘We don’t like the English.’

The other, who wore a tweed cap, said, ‘There’s only one thing we like about English girls, and that’s what’s between their legs, so let’s be having you.’

He leapt on her and she dropped the umbrella and tried to fight back as he forced her across the packing case, yanking up her dress.

‘Let me go, damn you!’ She clawed at his face, disgusted by the whiskey breath, aware of him forcing her legs open.

‘That’s enough,’ Rupert Lang called through the rain.

The man in the tweed cap turned and Grace pushed him away. The one with the ponytail turned, too, as Lang and Curry approached.

‘Just let her go,’ Curry said. ‘You made a mistake. Let’s leave it at that.’

‘You’d better keep out of this, friend,’ the man in the tweed cap told him. ‘This is Provisional IRA business.’

‘Really?’ Rupert Lang replied. ‘Well, I’m sure Martin McGuinness wouldn’t approve. He’s a family man.’

They were all very close together now. There was a moment of stillness and then the one with the ponytail pulled a Smith & Wesson .38 from the pocket of his bomber jacket. Rupert Lang’s hand came up holding the Beretta and shot him twice in the heart.

At the same moment, the man in the tweed cap knocked Grace sideways, sending her sprawling. He picked up a batten of wood and struck Lang across the wrist, making him drop the Beretta. The man scrambled for it, but it slid on the damp cobbles towards Grace. She picked it up instinctively, held it against him and pulled the trigger twice, blowing him back against the wall.

She stood there, legs apart, holding the gun in both hands, staring down at him.

Rupert Lang said, ‘Give it to me.’

‘Is he dead?’ she asked in a calm voice.

‘If not, he soon will be.’ Lang took the Beretta and shot him between the eyes. He turned to the one with the ponytail and did the same. ‘Always make sure. Now let’s get out of here.’ He picked up the umbrella. ‘Yours, I think.’

Curry took one arm, Lang the other, and they hurried her away.

‘No police?’ she said.

‘This is Belfast,’ Curry told her. ‘Another sectarian killing. They said they were IRA, didn’t they?’

‘But were they?’ she demanded as they took her down to the car and pushed her into the rear seat.

‘Probably not, my dear,’ Rupert Lang said. ‘Nasty young yobs cashing in. Lots of them about.’

‘Never mind,’ Curry told her. ‘They’ll be heroes of the revolution tomorrow.’

‘Especially if January 30 claims credit.’ Rupert Lang lit a cigarette and passed it to her. ‘Even if you don’t use these things, you could do with one now.’ She accepted it, strangely calm. ‘Do you need a doctor?’

‘No, he didn’t penetrate me if that’s what you mean.’

‘Good,’ Curry said. ‘Then it’s a hot bath and a decent night’s sleep and put it out of your mind. It didn’t happen.’

‘Oh, yes it did,’ she said and tossed the cigarette out of the window.

When they reached the Europa, Lang, a hand on her arm, started towards the lifts.

‘Actually,’ she said, ‘I’d like a nightcap.’

Lang frowned, then nodded. ‘Fine.’ He turned to Curry. ‘Better make the call, Tom.’ He led her into the Library Bar.

A few minutes later the phone rang on the desk of the night editor at the Belfast Telegraph. When he picked it up, a gruff voice said, ‘Carrick Lane, got that? You’ll find a couple of Provo bastards on their backs there. We won’t be sending flowers.’

‘Who is this?’ the night editor demanded.

‘January 30.’

The phone went dead. The night editor stared at it, frowning, then hurriedly dialled his emergency number to the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

Curry joined them in the bar at a corner table. They were drinking brandy and there was a glass for him.

Lang said, ‘You seem rather calm considering the circumstances.’

‘You mean why am I not crying and sobbing because I just killed a man?’ She shook her head. ‘He was a piece of filth. He deserved everything he got. I loathe people like that. When I was twelve I was driving back from a concert in Washington one night with my parents. We were attacked by armed thugs. My parents were killed.’

She sat staring down into her glass and Curry said gently, ‘I’m sorry.’

‘You handled the gun surprisingly well,’ Lang said. ‘Have you had much training?’

She laughed. ‘One Hollywood movie, just one. I didn’t like it out there. There were a few scenes where I had to use a gun. They showed me how.’ She finished the brandy and raised the empty glass to the barman. ‘Three more.’ She smiled tightly. ‘I hope you don’t mind, but we do seem to be rather tied in together, don’t we?’

‘Yes, you could say that,’ Curry agreed.

She turned to Lang as the barman brought the brandies and waited until he’d gone. ‘You said in the car something about January 30 claiming credit. I’ve read about them. They’re some sort of terrorist group, aren’t they?’

‘That’s right,’ Lang said. ‘Of course, in this sort of case, revolutionaries and so on, all sorts of groups like to claim credit. Very useful fact of life. We’re just making sure somebody does.’