In the Heart of the Sea: The Epic True Story that Inspired ‘Moby Dick’

As the men aloft wrestled with the canvas, the wind shifted into the northwest and the skies began to brighten. But the mood aboard the Essex sank into one of gloom. The ship had been severely damaged. Several sails, including both the main topgallant and the studding sail, had been torn into useless tatters. The cookhouse had been destroyed. The two whaleboats that had been hung off the port side of the ship had been torn from their davits and washed away, along with all their gear. The spare boat on the stern had been crushed by the waves. That left only two workable boats, and a whaleship required a minimum of three, plus two spares. Although the Essex’s stern boat could be repaired, they would be without a single spare boat. Captain Pollard stared at the splintered mess and declared that they would be returning to Nantucket for repairs.

His first mate, however, disagreed. Chase urged that they continue on, despite the damage. The chances were good, he insisted, that they would be able to obtain spare whaleboats in the Azores, where they would soon be stopping to procure fresh provisions. Joy sided with his fellow mate. The captain’s will was normally the law of the ship. But instead of ignoring his two younger mates, Pollard paused to consider their arguments. Four days into his first command, Captain Pollard reversed himself. “After some little reflection and a consultation with his officers,” Nickerson remembered, “it was deemed prudent to continue on our course and trust to fortune and a kind providence to make up our loss.”

The excuse given to the crew was that with the wind now out of the northwest, it would have taken too long to return to Nantucket. Nickerson suspected that Chase and Joy had other motives. Both knew that the men had not taken kindly to their treatment by the mates. Seeing the knockdown as a bad omen, many of the sailors had become sullen and sour. If they returned to Nantucket, some of the crew would jump ship. Despite the seriousness of the loss of the whaleboats, it was not the time to return to port.

Not surprisingly, given that he was the object of much of the crew’s discontent, Chase, in his own account of the accident, never mentions that Pollard originally proposed turning back. As Chase would have it, the knockdown was only a minor inconvenience: “We repaired our damage with little difficulty, and continued on our course.” But Nickerson knew differently. Many of the Essex’s men were profoundly shaken by the knockdown and wanted to get off the ship. Whenever they passed a homeward-bound vessel, the green hands would lament, in the words of one, “O, how I wish I was onboard with them going home again, for I am heartily sick of these whaling voyages”—even though they had not yet even seen a whale.

CHAPTER THREE

First Blood

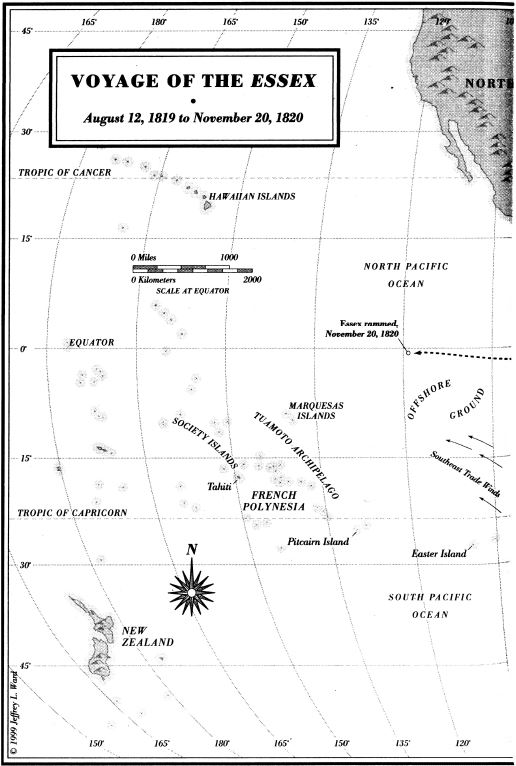

AFTER A PROVISIONING STOP in the Azores, which provided plenty of fresh vegetables but no spare whaleboats, the Essex headed south toward the Cape Verde Islands. Two weeks later they sighted Boavista Island. In contrast to the Azores’ green, abundant hills, the slopes of the Cape Verdes were brown and sere, with no trees to offer relief from the burning subtropical sun. Pollard intended to obtain some hogs at the island of Maio a few miles to the southwest.

The next morning, as they approached the island, Nickerson noticed that Pollard and his mates were strangely animated, speaking to each other with a conspiratorial excitement as they passed a spyglass back and forth, taking turns studying something on the beach. What Nickerson termed “the cause of their glee” remained a mystery to the rest of the crew until they came close enough to the island to see that a whaleship had been run up onto the beach. Here, perhaps, was a source of some additional whaleboats—something the men of the Essex needed much more desperately than pork.

Before Pollard could dispatch one of his own boats to the wreck, a whaleboat was launched from the beach and made its way directly toward the Essex. Aboard the boat was the acting American consul, Ferdinand Gardner. He explained that the wrecked whaler was the Archimedes of New York. While approaching the harbor she had struck a submerged rock, forcing the captain to run her up onto the beach before she was a total loss. Gardner had purchased the wreck, but he had only a single whaleboat left to sell.

While one was better than nothing, the Essex would still be dangerously low on boats. With this latest addition (and an old and leaky addition at that), the Essex would now have a total of four whaleboats. That would leave her with only one spare. In a business as dangerous as whaling, boats were so frequently damaged in their encounters with whales that many whaleships were equipped with as many as three spare boats. With a total of only four boats, the crew of the Essex would have scant margin for error. That was disturbing. Even the green hands knew that one day their lives could depend on the condition of these fragile cockleshells.

Pollard purchased the whaleboat, then sailed the Essex into the cove that served as Maio’s harbor, where pointed hills of bone-white salt—procured from salt ponds in the interior of the island—added a sense of desolation to the scene. The Essex anchored beside another Nantucket whaleship, the Atlantic, which was off-loading more than three hundred barrels of oil for shipment back to the island. Whereas Captain Barzillai Coffin and his crew could boast of the seven or so whales they’d killed since leaving Nantucket on the Fourth of July, the men of the Essex were still putting their ship back together after the knockdown in the Gulf Stream and had yet to sight a whale.

White beans were the medium of exchange on Maio, and with a cask of beans aboard, Pollard took a whaleboat in to procure some hogs. Nickerson was at the aft oar. The harbor was without any docks or piers, and in the high surf, bringing a whaleboat into shore was exceedingly tricky. Even though they approached the beach at the best possible part of the harbor, Pollard and his men ran into trouble. “Our boat was instantly capsized and overset in the surf,” Nickerson recalled, “and thrown upon the beach bottom upwards. The lads did not much mind this for none were hurt, but they were greatly amused to see the captain get so fine a ducking.”

Pollard traded one and a half barrels of beans for thirty hogs, whose squeals and grunts and filth turned the deck of the Essex into a barnyard. The impressionable Nickerson was disturbed by the condition of these animals. He called them “almost skeletons,” and noted that their bones threatened to pierce through their skin as they walked about the ship.

NOT until the Essex had crossed the equator and reached thirty degrees south latitude—approximately halfway between Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires—did the lookout sight the first whale of the voyage. It required sharp eyes to spot a whale’s spout: a faint puff of white on the distant horizon lasting only a few seconds. But that was all it took for the lookout to bellow, “There she blows!” or just “B-l-o-o-o-w-s!”

After more than three whaleless months at sea, the officer on deck shouted back in excitement, “Where away?” The lookout’s subsequent commentary not only directed the helmsman toward the whales but also worked the crew into an ever increasing frenzy. If he saw a whale leap into the air, the lookout cried, “There she breaches!” If he caught a glimpse of the whale’s horizontal tail, he shouted, “There goes flukes!” Any indication of spray or foam elicited the cry “There’s white water!” If he saw another spout, it was back to “B-l-o-o-o-w-s!”

Under the direction of the captain and the mates, the men began to prepare the whaleboats. Tubs of harpoon line were placed into them; the sheaths were taken off the heads of the harpoons, or irons, which were hastily sharpened one last time. “All was life and bustle,” remembered one former whaleman. Pollard’s was the single boat kept on the starboard side. Chase’s was on the aft larboard, or port, quarter. Joy’s was just forward of Chase’s and known as the waist boat.

Once within a mile of the shoal of whales, the ship was brought to a near standstill by backing the mainsail. The mate climbed into the stern of his whaleboat and the boatsteerer took his position in the bow as the four oarsmen remained on deck and lowered the boat into the water with a pair of block-and-tackle systems known as the falls. Once the boat was floating in the water beside the ship, the oarsmen—either sliding down the falls or climbing down the side of the ship—joined the mate and boatsteerer. An experienced crew could launch a rigged whaleboat from the davits in under a minute. Once all three whaleboats were away, it was up to the three shipkeepers to tend to the Essex.

At this early stage in the attack, the mate or captain stood at the steering oar in the stern of the whaleboat while the boatsteerer manned the forward-most, or harpooner’s oar. Aft of the boatsteerer was the bow oarsman, usually the most experienced foremast hand in the boat. Once the whale had been harpooned, it would be his job to lead the crew in pulling in the whale line. Next was the midships oarsman, who worked the longest and heaviest of the lateral oars—up to eighteen feet long and forty-five pounds. Next was the tub oarsman. He managed the two tubs of whale line. It was his job to wet the line with a small bucketlike container, called a piggin, once the whale was harpooned. This wetting prevented the line from burning from the friction as it ran out around the loggerhead, an upright post mounted on the stern of the boat. Aft of the tub oarsman was the after oarsman. He was usually the lightest of the crew, and it was his job to make sure the whale line didn’t tangle as it was hauled back into the boat.

Three of the oars were mounted on the starboard side of the boat and two were on the port side. If the mate shouted, “Pull three,” only those men whose oars were on the starboard side began to row. “Pull two” directed the tub oarsman and bow oarsman, whose oars were on the port side, to row. “Avast” meant to stop rowing, while “stern all” told them to begin rowing backward until sternway had been established. “Give way all” was the order with which the chase began, telling the men to start pulling together, the after oarsman setting the stroke that the other four followed. With all five men pulling at the oars and the mate or captain urging them on, the whaleboat flew like a slender missile over the wave tops.

The competition among the boat-crews on a whaleship was always spirited. To be the fastest gave the six men bragging rights over the rest of the ship’s crew. The pecking order of the Essex was about to be decided.

With nearly a mile between the ship and the whales, the three crews had plenty of space to test their speed. “This trial more than any other during our voyage,” Nickerson remembered, “was the subject of much debate and excitement among our crews; for neither was willing to yield the palm to the other.”

As the unsuspecting whales moved along at between three and four knots, the three whaleboats bore down on them at five or six knots. Even though all shared in the success of any single boat, no one wanted to be passed by the others; boat-crews were known to foul one another deliberately as they raced side by side behind the giant flukes of a sperm whale.

Sperm whales are typically underwater for ten to twenty minutes, although dives of up to ninety minutes have been reported. The whaleman’s rule of thumb was that, before diving, a whale blew once for each minute it would spend underwater. Whalemen also knew that while underwater the whale continued at the same speed and in the same direction as it had been traveling before the dive. Thus, an experienced whaleman could calculate with remarkable precision where a submerged whale was likely to reappear.

Nickerson was the after oarsman on Chase’s boat, placing him just forward of the first mate at the steering oar. Chase was the only man in the boat who could actually see the whale up ahead. While each mate or captain had his own style, they all coaxed and cajoled their crews with words that evoked the savagery, excitement, and the almost erotic bloodlust associated with pursuing one of the largest mammals on the planet. Adding to the tension was the need to remain as quiet as possible so as not to alarm or “gally” the whale. William Comstock recorded the whispered words of a Nantucket mate:

Do for heaven’s sake spring. The boat don’t move. You’re all asleep; see, see! There she lies; skote, skote! I love you, my dear fellows, yes, yes, I do; I’ll do anything for you, I’ll give you my heart’s blood to drink; only take me up to this whale only this time, for this once, pull. Oh, St. Peter, St. Jerome, St. Stephen, St. James, St. John, the devil on two sticks; carry me up; O, let me tickle him, let me feel of his ribs. There, there, go on; O, O, O, most on, most on. Stand up, Starbuck [the harpooner]. Don’t hold your iron that way; put one hand over the end of the pole. Now, now, look out. Dart, dart.

As it turned out, Chase’s crew proved the fastest that day, and soon they were within harpooning distance of the whale. Now the attention turned to the boatsteerer, who had just spent more than a mile rowing as hard as he possibly could. His hands were sore, and the muscles in his arms were trembling with exhaustion. All the while he had been forced to keep his back turned to a creature that was now within a few feet, or possibly inches, of him, its tail—more than twelve feet across—working up and down within easy reach of his head. He could hear it—the hollow wet roar of the whale’s lungs pumping air in and out of its sixty-ton body.

But for Chase’s novice harpooner, the twenty-year-old Benjamin Lawrence, the mate himself was as frightening as any whale. Having been a boatsteerer on the Essex’s previous voyage, Chase had definite ideas on how a whale should be harpooned and maintained a continual patter of barely audible, expletive-laced advice. Lawrence tucked the end of his oar handle under the boat’s gunnel, then braced his leg against the thigh thwart and took up the harpoon. There it was, the whale’s black body, glistening in the sun. The blowhole was on the front left side of the head, and the spout enveloped Lawrence in a foulsmelling mist that stung his skin.

By hurling the harpoon he would transform this gigantic, passive creature into an angry, panicked monster that could easily dispatch him into the hereafter with a single swipe of that massive tail. Or, even worse, the whale might turn around and come at them with its tooth-studded jaw opened wide. New boatsteerers had been known to faint dead away when first presented with the terrifying prospect of attaching themselves to an infuriated sperm whale.

As Lawrence stood at the tossing bow, waves breaking around him, he knew that the mate was analyzing every one of his movements. If he let Chase down now, there would be hell to pay.

“Give it to him!” Chase bawled. “Give it to him!”

Lawrence hadn’t moved when there was a sudden splintering crack and crunch of cedar boards, and he and the other five men were airborne. A second whale had come up from beneath them, giving their boat a tremendous whack with its tail and pitching them into the sky. The entire side of the whaleboat was stove in, and the men, some of whom could not swim, clung to the wreck. “I presume the monster was as much frightened as ourselves,” Nickerson commented, “for he disappeared almost instantly after a slight flourish of his huge tail.” To their amazement, no one was injured.

Pollard and Joy abandoned the hunt and returned to pick up Chase’s crew. It was a dispiriting way to end the day, especially since they were once again down a whaleboat, a loss that, in Nickerson’s words, “seemed to threaten the destruction of our voyage.”

SEVERAL days after Chase’s boat was repaired, the lookout once again sighted whales. The boats were dispatched, a harpoon was hurled—successfully—and the whaleline went whizzing out until it was finally snubbed at the loggerhead, launching the boat and crew on the voyage’s first “Nantucket sleigh ride,” as it would come to be called.

Merchant seamen spoke derisively about the slow speeds of the average bluff-bowed whaleship, but the truth of the matter was that no other sailors in the early nineteenth century experienced the speeds of Nantucket whalemen. And, instead of doing it in the safe confines of a large, three-masted ship, the Nantucketer traveled in a twenty-five-foot boat crammed with half-a-dozen men, rope, and freshly sharpened harpoons and lances. The boat rocked from side to side and bounced up and down as the whale dragged it along at speeds that would have left the fleetest naval frigate wallowing in its wake. When it came to sheer velocity over the water, a Nantucketer—pinned to the flank of a whale that was pulling him miles and miles from a whaleship that was already hundreds of miles from land—was the fastest seaman in the world, traveling at fifteen (some claimed as many as twenty) bone-jarring knots.

The harpoon did not kill the whale. It was simply the means by which a whaleboat crew attached itself to its prey. After letting the creature tire itself out—by sounding to great depths or simply tearing along the water’s surface—the men began to haul themselves, inch by inch, to within stabbing distance of the whale. By this point the boatsteerer and the mate had traded places, a miraculous feat in its own right on a craft as small and tender as a whaleboat. Not only did these two men have to contend with the violent slapping of the boat through the waves—which could be so severe that nails started from the planks in the bow and stern—but they had to stay clear of the whale line, quivering like a piano wire down the centerline of the boat. Eventually, however, the boatsteerer made it aft to the steering oar and the mate, who was always given the honor of the kill, took up his position in the bow.

If the whale was proving too spirited, the mate would hobble it by taking up a boat-spade and hacking away at the tendons in the tail. Then he’d take up the eleven- to twelve-foot-long killing lance, its petal-shaped blade designed for piercing a whale’s vital organs. But finding “the life” of a giant swimming mammal encased in a thick layer of blubber was not easy. Sometimes the mate would be forced to stab it as many as fifteen times, probing for a group of coiled arteries in the vicinity of the lungs with a violent churning motion that soon surrounded the whaleboat in a rushing river of bright red blood.

When the lance finally found its mark, the whale would begin to choke on its own blood, its spout transformed into a fifteen- to twenty-foot geyser of gore that prompted the mate to shout, “Chimney’s afire!” As the blood rained down on them, the men took up the oars and backed furiously away, then paused to watch as the whale went into what was known as its flurry. Beating the water with its tail, snapping at the air with its jaws—even as it regurgitated large chunks of fish and squid—the creature began to swim in an ever tightening circle. Then, just as abruptly as the attack had begun with the first thrust of the harpoon, it ended. The whale fell motionless and silent, a giant black corpse floating fin-up in a slick of its own blood and vomit.

This may have been the first time Thomas Nickerson had ever helped kill a warm-blooded animal. Back on Nantucket, where the largest wild quadruped was the Norway rat, there were no deer or even rabbits to hunt. And as any hunter knows, killing takes some getting used to. Even though this brutal and bloody display was the supposed dream of every young man from Nantucket, the sentiments of an eighteen-year-old green hand, Enoch Cloud, who kept a journal during his voyage on a whaleship, are telling: “It is painful to witness the death of the smallest of God’s created beings, much more, one in which life is so vigorously maintained as the Whale! And when I saw this, the largest and most terrible of all created animals bleeding, quivering, dying a victim to the cunning of man, my feelings were indeed peculiar!”

THE dead whale was usually towed back to the ship headfirst. Even with all five men rowing—the mate at the steering oar sometimes lending a hand to the after oarsman—a boat towing a whale could go no faster than one mile per hour. It was dark by the time Chase and his men reached the ship.

Now it was time to butcher the body. The crew secured the whale to the Essex’s starboard side, with the head toward the stern. Then they lowered the cutting stage—a narrow plank upon which the mates balanced as they cut up the body. Although the stripping of a whale’s blubber has been compared to the peeling of an orange, it was a little less refined than that.

First the mates hacked a hole in the whale’s side, just above the fin, into which was inserted a giant hook suspended from the mast. Then the immense power of the ship’s windlass was brought to bear, heeling the ship over on its side as the block-and-tackle system attached to the hook creaked with strain. Next the mates cut out the start of a five-foot-wide strip of the blubber adjacent to the hook. Pulled by the tackle attached to the windlass, the strip was gradually torn from the whale’s carcass, slowly spinning it around, until a twenty-foot-long strip, dripping with blood and oil, was suspended from the rigging. This “blanket piece” was severed from the whale and lowered into the blubber room belowdecks to be cut into more manageable pieces. Back at the corpse, the blubber-ripping continued.

Once the whale had been completely stripped of blubber, it was decapitated. A sperm whale’s head accounts for close to a third of its length. The upper part of the head contains the case, a cavity filled with up to five hundred gallons of spermaceti, a clear, high-quality oil that partially solidifies on exposure to air. After the ship’s system of blocks and tackles hauled the head up onto the deck, the men cut a hole into the top of the case and used buckets to remove the oil. One or two men might then be ordered to climb into the case to make sure all the spermaceti had been retrieved. Spillage was inevitable, and soon the decks were a slippery mess of oil and blood. Before cutting loose the whale’s mutilated corpse, the mates probed its intestinal tract with a lance, searching for an opaque, ash-colored substance called ambergris. Thought to be the result of indigestion or constipation on the part of the whale, ambergris is a fatty substance used to make perfume and was worth more than its weight in gold.

By now, the two immense, four-barreled iron try-pots were full of pieces of blubber. To hasten the trying-out process, the blubber was chopped into foot-square hunks, then cut through into inch-thick slabs that resembled the fanned pages of a book and were known as bible leaves. A whale’s blubber bears no similarity to the fat reserves of terrestrial animals. Rather than soft and flabby, it is tough, almost impenetrable, requiring the whalemen to resharpen their cutting tools constantly.

Wood was used to start the fires beneath the try-pots, but once the boiling process had begun, the crispy pieces of blubber floating on the surface of the pot—known as scraps or cracklings—were skimmed off and tossed into the fire for fuel. The flames that melted down the whale’s blubber were thus fed by the whale itself. While this was a highly efficient use of materials, it produced a thick pall of black smoke with an unforgettable stench. “The smell of the burning cracklings is too horribly nauseous for description,” remembered one whaleman. “It is as though all the odors in the world were gathered together and being shaken up.”